Seeing the huge response to the pieces we’ve published about mental health over the last few years has been hugely gratifying, as photography is about much more than f stops, ISO wrangling or the arcana of lenses. Photography fascinates us because of its infinite variety: it’s an art, a science, a tool to enhance our well-being, and a lot more besides.

This year has been particularly difficult for anyone struggling with inner demons, and although the worst of the lockdown isolation is hopefully over for many, this wretched, ongoing virus is hardly conducive to optimism. We are where we are, however, and one big positive to come out of 2020 has been the growing appreciation of photography’s power to help us cope with difficult times. Maybe it’s because taking pictures often gets you out into nature and away from your ‘washing machine’ head, or the false refuge of your bed; maybe it’s because taking a good picture requires a lot of focus and concentration, occupying the brain and helping de-amplify worry and bleak thoughts.

Even if you can only meet other camera club members through Zoom, it keeps us connected to our fellows, too, easing the corrosion of loneliness. Over the next few pages, we’re delighted to present some inspiring case studies from a wide range of photographers facing mental and sometimes physical challenges. This is certainly not the last word, so please continue to share your stories via our Facebook and Twitter pages.

Steve Macleod

Professor Steve Macleod is a highly experienced photographer and currently works as director of Metro Imaging, a well-established printing, framing and retouching service based in central London. Steve also has bipolar disorder. ‘On a creative level, I find that the act of making photographs and prints is something that I use in support of my health, and being outside in nature is where I am most inspired. On a practical level it provides order and discipline, something that I require as part of my coping strategy and from an emotional context it allows me the freedom to express myself.’

I was coming to terms with having to take medication for the rest of my life. The leaves represented change and my understanding that I had to let go before I could move forward

As Steve explains, there is something about being out in nature, which really helped him manage his condition, which seems to be one of the core benefits of photography when it comes to mental health. ‘Many years ago I had gone through a challenging episode with my health and gave up on photography and pretty much everything else. I was out walking in a forest near my parents’ home in the Highlands and saw a striking silver birch tree in amongst some pines. It was a simple image but it resonated with me. It was then that I decided that I would use photography in a different way – it was not only about documenting the world around me but also as a way of expressing how I felt and it slowly built into something that has supported me ever since. I am not that interested in photography in as much as what photography can do both for oneself and for others.’

I would have recurring dreams of mountains all coloured dark blue and indigo (a colour associated with depression)

When Steve is on a ‘high,’ he will often take himself away outside in the natural environment ‘so that I can channel my energy, as it helps me process and manage my behaviour.’ Steve shoots large format most of the time and finds the act of making photographs this way is slower and more controlled; it feels less ‘frantic’ than with smaller formats. ‘I spend a great deal of time composing images so the process of making – rather than the photograph itself – is when I am at peace. Being in the landscape and feeling a part of it runs deep with my Pictorialism beliefs – I always try to convey an emotion rather than a prescriptive rendering of the landscape.’ Like most people, Steve has tried a range of genres and now feels he has found the right balance, both creatively and for his overall well-being.

‘My work now says as much about me and the way I feel as it does the subject I am working with. I’ve learned over the years to be honest with myself and my work whereas previously I was always trying to be something or somebody else.’ Steve talks the talk as well as walking the walk and is a keen advocate for challenging perceptions around mental health. ‘I have overcome stigma through my own experiences and having spent time in secure units, I consider myself very fortunate in being able to work through and understand my own condition. As a result I work closely with charities and institutions in support of mental health and well-being, such as Hospital Rooms. We are also in the process of launching an online Art Academy, which puts mental health and well-being front and centre of the programme. Education is an important part of my life.’ For more details, see Steve’s website.

Tony Fisher

Tony is another experienced and widely exhibited photographer, who is the recipient of several Arts Council grants, and features in the Historic England collection. Tony’s mental health struggles have included battling loneliness, PTSD, anxiety and depression, along with physical health issues. ‘I didn’t suddenly wake up one day and say I wanted to focus on mental health issues,’ he explains. ‘Back in the 90s, I was working as a photography lecturer and freelancer. Then my wife, who was only in her 40s, became ill with motor neurone disease. Within a few weeks I not only lost her, but both of my parents as well. I become quite ill with the stress and bereavement, and the responsibility of having to raise kids. I couldn’t work properly for quite a number of years, which is when I began to discover photography’s healing power.’

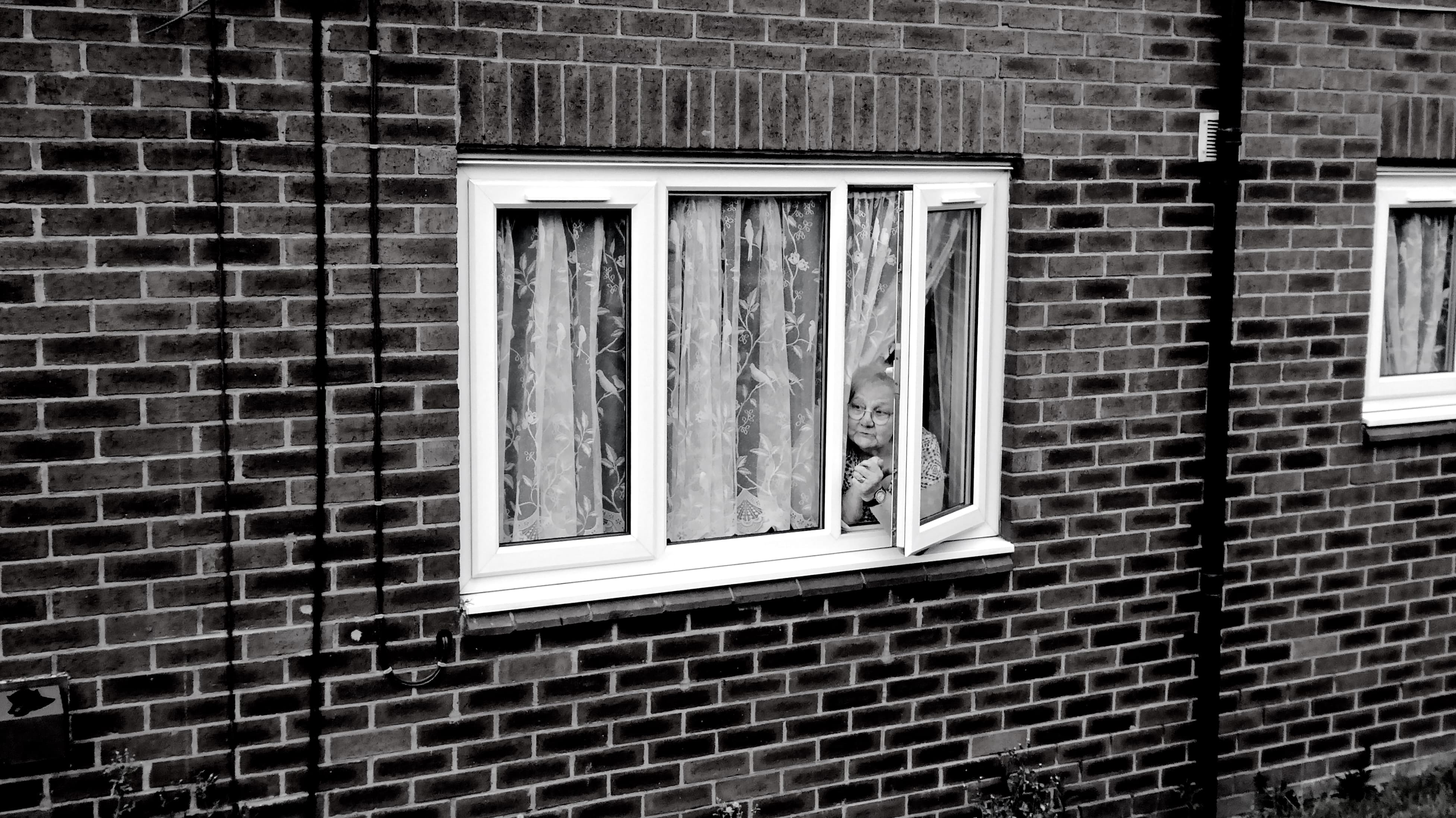

Clapping for the NHS. Guinness Sheltered Housing, Riddings, Derbyshire 2020

Tony soldiered on, exhibiting regularly as well as doing some major freelance projects for Nottinghamshire County Council. Another big breakthrough came in 2019, when he successfully pitched an idea for an exhibition on loneliness to the Arts Council. This enabled him to travel up and down the country documenting the effect of isolation on people – but then the virus struck this year. Forced to adapt, he turned to taking portraits of people during the lockdown. As well as finding photography personally beneficial, Tony is involved with the mental health charity, Rethink Mental Illness, which has set up specialist photography groups for people at its drop-in centres (it is hoped these will resume as soon as possible). Tony has also seen his photography change as he has found some healing through taking pictures. ‘I started off doing depressing black & white work, but my images have got brighter now – much more concerned with light and nature.

Campervan Dreams – Stewart Cox, Belper, Derbyshire, 2020

I have emerged into the light. ‘Photography means I always have something to look forward to – there is always something interesting to pursue, and it’s a great way to occupy the mind. I am not getting any younger so I want to take the best pictures I can. I also like to help others, and this has also helped me cope better with my issues.’ Photographs can also help to capture a sense of hope, which Tony thinks is also crucial in helping people to cope with mental health struggles during this very challenging year. ‘I recently took an image of a guy who was confined to his house owing to medical conditions, holding two model camper vans. Camper vans are his passion, and he can’t wait until he can get out again. And he will.’ For more details, see www.anthonyfisherphotography.co.uk.

Pete Reed OBE

Rowing fans may already be familiar with Pete’s name: as a key member of the GB rowing team he won three Olympic gold medals. His life changed a year ago, however, when he suffered a rare spinal stroke during a military training course – leaving him paralysed from the chest down at the age of 38. Photography has always been a passion of Pete’s and this has continued after the stroke, so we caught up to find out how it’s helped him cope. ‘I promised myself a few things at the start of this transition from being very able to being paralysed: don’t dwell, work hard, never give up and don’t be a sob story,’ Pete explains. ‘

‘After days of captivity in my own body, this was the first time I was able to touch sunlight from a strapped ride in an ambulance’

Remembering the past and planning for the future can be overwhelming so I wanted a friend with me to help keep me mindful. The camera keeps me in the moment. I am unable to dwell or get distracted with future uncertainties.’ Even a disciplined high achiever like Pete must have gone through some rough times mentally when he realised the implications of the stroke. So did taking photos take his mind off things? ‘I went to hospital very fit and strong and watched all the muscles below my chest slowly waste away through inactivity. It is brutal.

At first I found it hard to even look at the shocking change and new reality. The aim of photography wasn’t to take my mind off that, but to face up to it. I am lucky to still have my arm strength and my mind is still as average as it ever was, so there is no excuse for not continuing with my photography passion. I have some personal photographs that I took of my changing body; it’s like standing up to a bully. Once it is done, you can move on with strength, but if you don’t face the challenge, it will always keep a hold of you.

‘We were both exhausted. Jeannie was always by my side and I was delighted to see her resting for once’

Photography won that war for me very early on by facilitating the necessary brave actions.’ So what would Pete say to people who aren’t facing the same physical challenges as him, but still feel overwhelmed with anxiety and depression? ‘Responding to trauma is perfectly normal and part of a healthy process. Whilst anxiety and depression are horrendous, even recognising that you are suffering deeply is part of the process to come back to a more positive place. I have found that creating and documenting, even in very hard times and of difficult subject matter, has been therapeutic. Creating something as simple as an image has sometimes been the only thing I have been able to do in a whole day. That really has been a lifeline that I am so grateful for. Please pick up your camera like a warrior picks up a sword.’

As Pete explains, he has gone from standing 6½ft to about 4ft in his wheelchair, and this has literally changed his angle on photography. ‘I have a new world of perspectives to explore. There are clear limitations with where I can go and how I can move, but that makes things different and not necessarily worse. Along with my precious Fujifilm X-T4 I am increasingly using smaller primes like the 16mm f/2.8 and 50mm f/2, and I am learning that they are no compromise. I have to shoot with one hand now to support my body with the other, so a small system and IBIS on that model are so helpful.’ See Instagram.com/PeteReed to keep up with Pete’s photography and daily updates.

Martin Leighton

Martin is a keen landscape photographer who, like many of us, struggled during the lockdown. ‘Photography has been the light in my darkness,’ he explains. ‘For me, losing my freedom made me appreciate how beautiful the natural world is. My big film camera also broke during lockdown which was devastating, but this was a blessing in disguise as I bought a Canon EOS 5Ds – I realised how digital is awesome and so much easier.’ For Martin, photography was really helpful for keeping him calm.

‘It soothed the woes and suppressed all the horrible news. When you are artistically challenged, you find ways of expressing yourself, and discover parts of the brain that you never really use. Going out to a beautiful place at sunrise with your camera actually gives you an excuse to be in that place and can help you work stuff out, especially when you are feeling low. Seeing the world in great light kind of puts your woes into perspective. Landscape photography can teach you that life goes on and also that nature is strong – so should you be.’

Ian Palmer

‘I’ve had poor mental health for the last 25 years and have been on medication for 16,’ Ian explains. ‘Ever since I was a kid I’ve had a camera and have always enjoyed photography.’ Two years ago, Ian suffered a mental breakdown and came very close to ending his life. ‘Thankfully I found some support from a mental health charity and although things are better, I am still not well.’ He then decided to join a local camera club, which proved to be a breakthrough.

‘My mental health has continued to improve, as well as my photography skills. I bought a new camera at the end of 2019, a Canon 4000D, then a nifty-fifty lens. Since lockdown, I’ve entered several competitions, which has given me a focus that wasn’t in my brain before. It’s also given me a sense of achievement and a new confidence in my photographical skills. Considering I had a career in a creative and highly skilled industry, it’s been wonderful to get that back in my life, but without the pressures of the workplace.’ See twitter.com/ianjpalmer.

Fo Bugler

Fo came to appreciate the healing power of photography after realising it could help her come to terms with a lifelong fear of heights. ‘I am also diagnosed with clinical depression, and when photographing, I usually want to be on my own,’ she explains. ‘Whether walking in Dorset woodlands or travelling abroad, I prefer to focus solely on what I see through the lens. It is a form of escapism… (my subjects) can all lose me to the moment, and my fears and anxieties fade into the background.’

Fo is unable to function physically and mentally during bad episodes of depression. ‘Luckily, the artistic side of life helps to rebalance me when I am coming out if it. It’s my therapy. Not only does the camera act as a physical barrier between me and the world I might be struggling to face, I also enjoy getting lost in creative editing too.’ She particularly enjoys reportage, travel, festival and street photography. ‘But what I favour above all is constructing and manipulating images using ICM, digital painting and overlaid photos, for example. I urge anyone who struggles with their mental health, in any way, to find something creative (and/or physical) to shift their focus towards.’ See her Facebook page.

Victoria Hiscock

Life has not been easy for Victoria, but she’s come out on top with the help of photography. ‘Having struggled with mental health throughout my adolescence and beyond, I naturally started struggling again after I found myself raising my son alone.’ Victoria had always enjoyed taking photos but the turning point came when a baby polar bear was born in the Scottish Highland Wildlife Park. ‘

I took my son to see it and my brother offered to lend me his DSLR. It was there that I found my passion for wildlife photography.’ Victoria enrolled on a part-time photography course to start that September, and by November she was being shortlisted for both local and national competitions. ‘Photography saved me. It is my therapy when I’m feeling down and my escape when I feel alone. Not only is it amazing to spend time in nature, but you meet people, too.’ For more, see @victoria_rose_photography on Instagram.