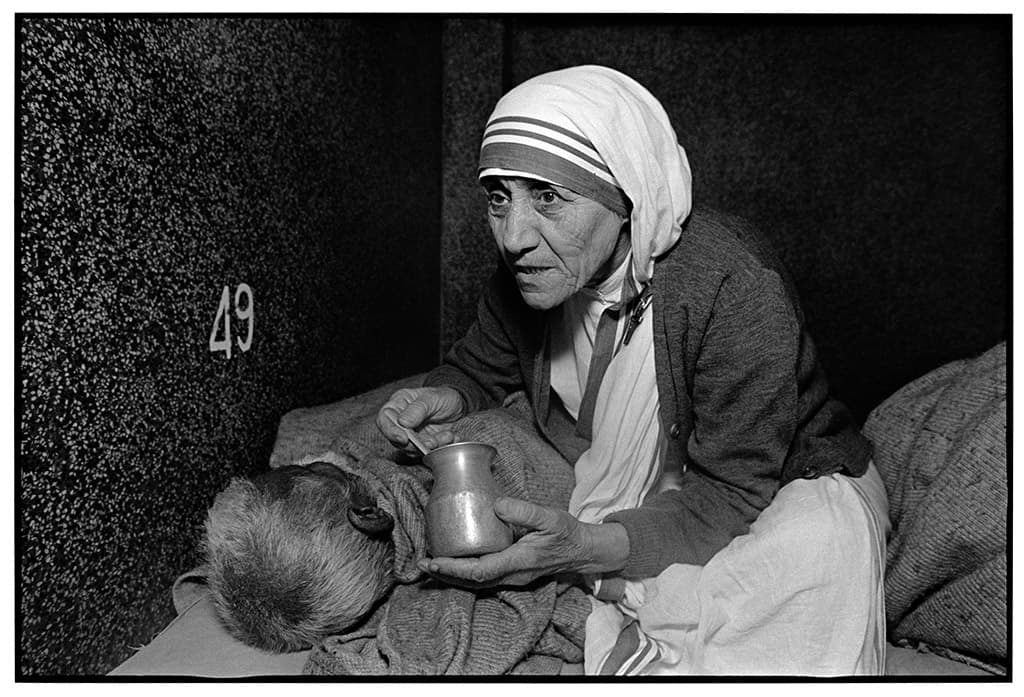

Mary Ellen Mark was a highly influential and respected photographer during her 50-year-plus working career, which spanned from the mid-1960s till her death in 2015. She was a pioneer in the art of empathy

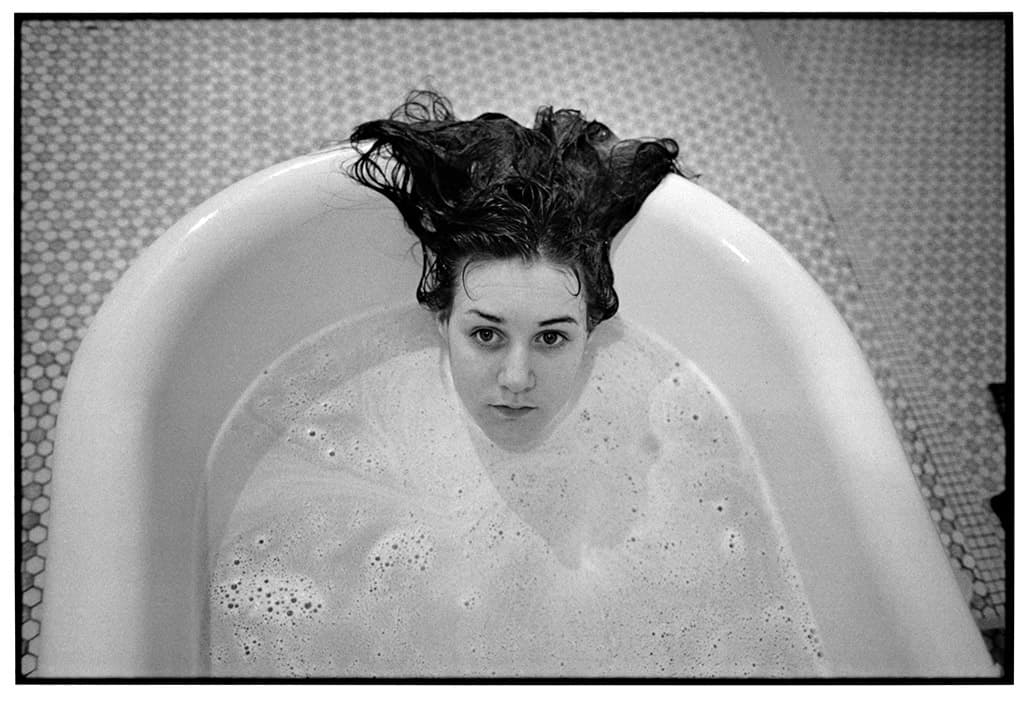

and embedding herself with her subjects – from poverty-stricken families in the US to prostitutes in the brothels of Bombay – while never judging her subjects, purely telling their stories with her amazing photographic eye.

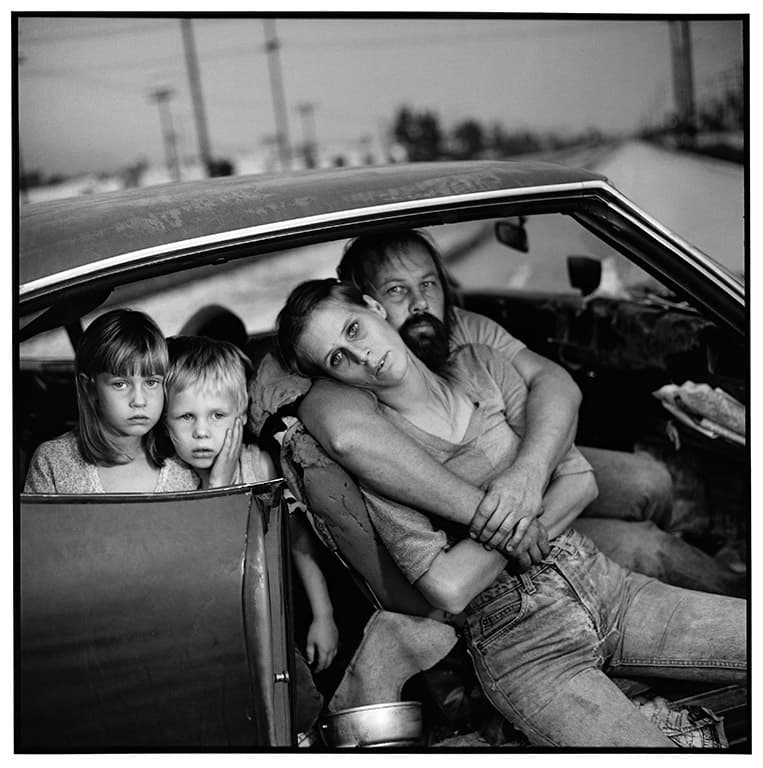

Crissy, Jesse, Linda and Dean Damm in their car. Los Angeles, 1987

As a child Mark had a Box Brownie camera but she decided to study painting and art history for her initial degree. Her photographic career began in 1964 after she’d completed a Master’s degree in photojournalism at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania and the following year her travels began when she went to Turkey for a year on a Fulbright Scholarship (a US cultural exchange programme).

While overseas, Mark took the opportunity to also shoot in England, Germany, Greece, Italy and Spain. The resulting work ended up in her first published book, Passport, in 1974. Though originally from Pennsylvania, Mark moved to New York after returning from Turkey and began documenting anti-Vietnam War demos, transvestite culture, the women’s liberation movement and more – it was then that the roots of her work around issues of social justice were firmly planted.

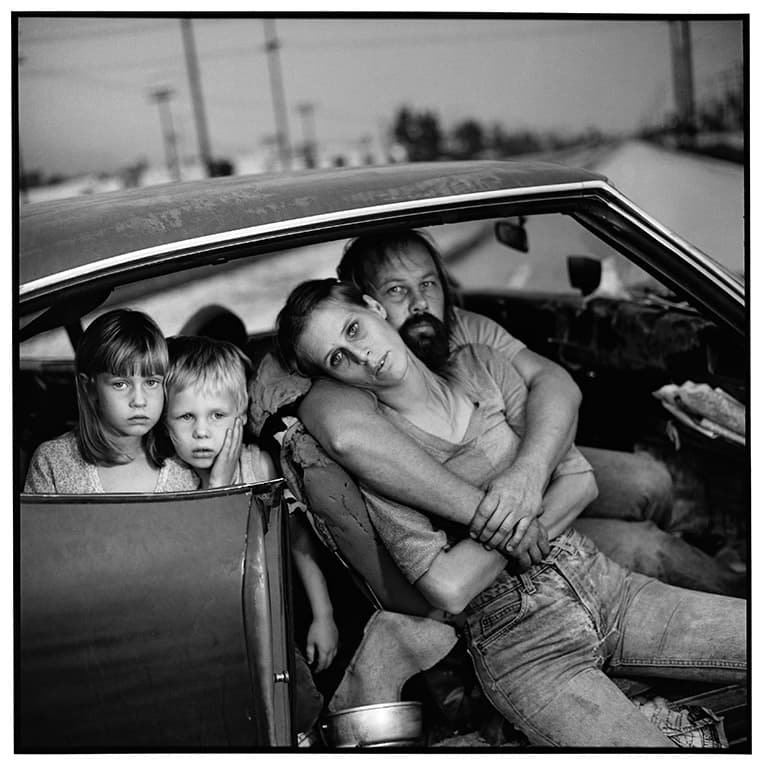

Laurie in the bathtub of Ward 81, Oregon State Hospital, Salem, Oregon, 1976

Mark once revealed, ‘I feel an affinity for people who haven’t had the best breaks in society. What I want to do more than anything is to acknowledge their existence.’

This penchant for highlighting the struggles of those who suffered hardship, mental illness and homelessness is dotted throughout her stunning body of work. For her Ward 81 project she lived for six weeks with the patients in a women’s security ward of Oregon State Hospital and for her Falkland Road project Mark spent three months documenting the lives of prostitutes on a single street in Bombay, India.

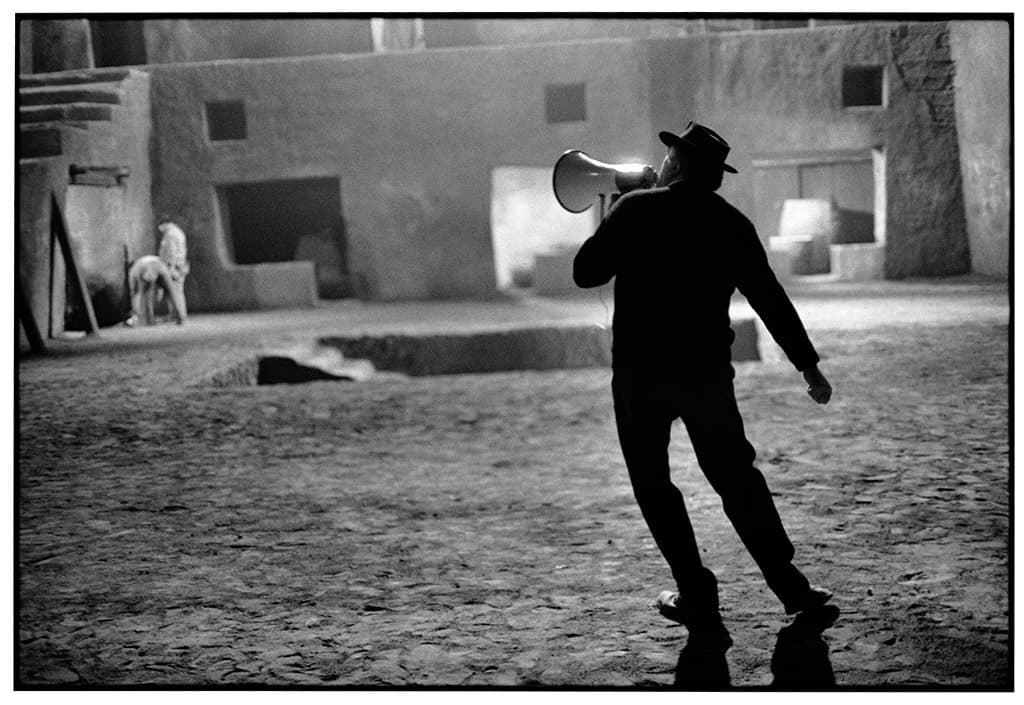

Alongside her documentary work Mark also developed a career as an on-set stills photographer on over 100 major motion pictures, including Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, Federico Fellini’s Satyricon and Mike Nichols’s Carnal Knowledge.

Indeed Mark would meet her husband, filmmaker Martin Bell, in 1980 on the set of Milos Forman’s Ragtime, which saw the final screen appearance of James Cagney. During her career Mark worked with a number of photographic formats from 35mm, 120, 220, 4x5in all the way up to a 20x24in Polaroid Land Camera and was also a teacher of photography – at the International Center of Photography (ICP) in New York, the Center for Photography at Woodstock and in Mexico – for several decades.

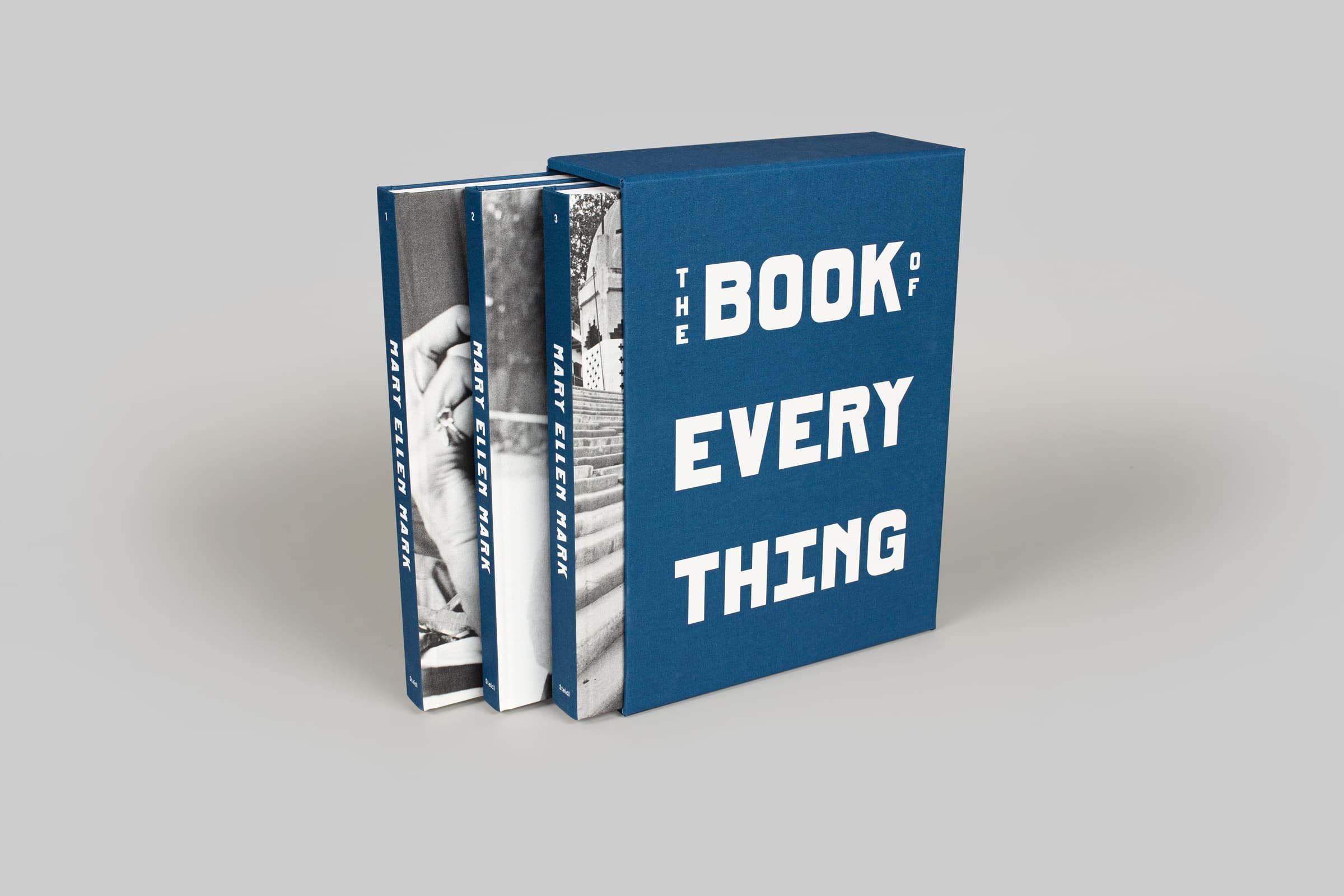

Sadly, Mark passed away of blood cancer in May 2015, aged 75, but that proved to be the trigger for the creation of a new three-volume set of books called The Book of Everything. The project showcases Mark’s work over the decades and includes hundreds of her iconic, timeless images from around the world. To get the inside story of the project AP spoke to Mary Ellen Mark’s husband, Martin Bell.

Mother Teresa feeding a man at the Home for the Dying, Mother Teresa’s Missionaries of Charity, Kolkata, India, 1980

What drove the idea for The Book of Everything?

I thought of making this book when Mary Ellen died on 25 May 2015 of MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome, a blood cancer. The idea was to give a sense of the extraordinary and passionate life she had making these images. It would be a “book of everything”.

The book would contain fragments of text, recollections from friends and people she had photographed, and Mary Ellen’s thoughts on her journey through it all, with excerpts from her own journals and notes. It would be in roughly chronological order, a visual diary of her life’s experiences. A compassionate human record, without judgement.

My original concept for the book was it should be one volume. By the time we had completed the edit there were 880 pages and Gerhard Steidl, the publisher, beat sense into my head, but nicely. He told me the bindery was not able to bind that many pages. I realised then that only Olympic weightlifters would have been able to lift the book… a limited market! So The Book of Everything is in three volumes and lives inside a beautiful slipcase.’

Marina Campa as Batman’s grandmother, Kimberly Crown Circus. Mexico City, 1997

How did you do the image edit for the books?

We began digitising Mary Ellen’s archive in 1987, scanning and cataloguing her selections from contact sheets. This database is the core of the archive and grew to 63,000 images by the time Mary Ellen died. When we started this book, we turned to this database, but soon realised there may have been frames that were missed. We had no choice but to go back to Mary Ellen’s archive of contact sheets and look at all the images.

In 2016 I started looking through the thousands of contact sheets and chromes. I looked at every frame, of which there were more than two million. I noted Mary Ellen’s 63,110 selects, to these I added 5,977 images of my own choice that I thought she had missed or had marked and were not in the database.

Meredith Lue, Mary Ellen’s library manager for 20 years, and Julia Bezgin, Mary Ellen’s studio manager for 12 years, and I edited down the thousands of frames to the 515 plates that are in the book. It took us four years to put this book together.

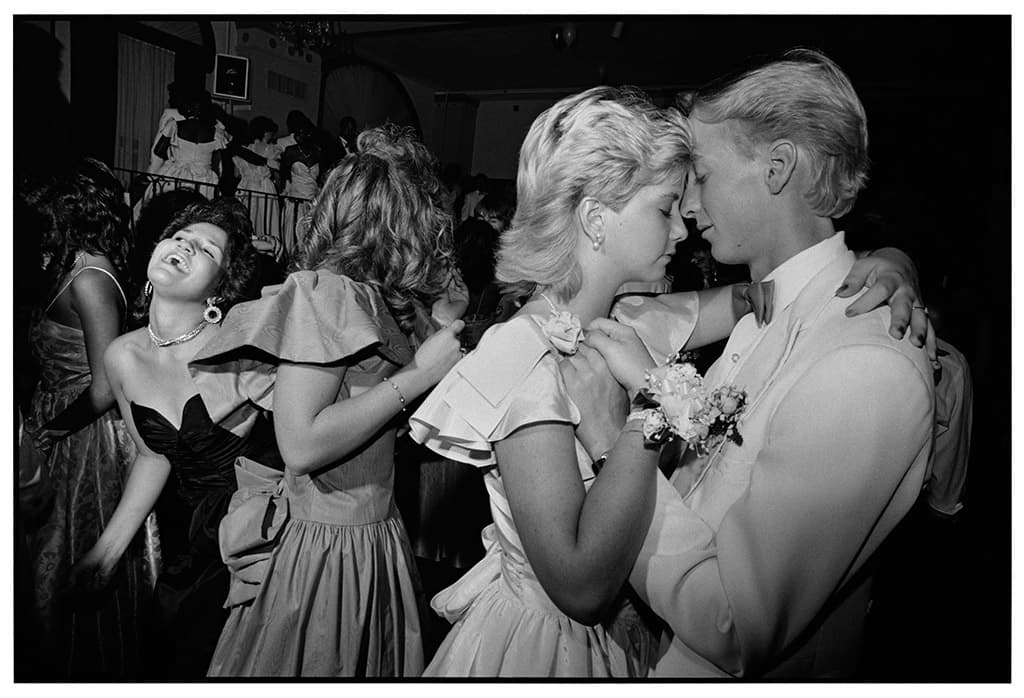

Brooke and Billy at Gibbs Senior High School Prom, St. Petersburg, Florida, 1986

Are you happy with the books?

Every person who worked on it brought only the best of themselves. Chuck Kelton, who had made silver prints for Mary Ellen for some 20 years, made a complete set of new black & white silver prints for the book’s plates. Sonya Dyakova created the beautiful design for the book.

Gerhard Steidl, the master printer and book publisher, orchestrated all the elements that made Mary Ellen’s work come to life on the printed page. It was a great pleasure for me, along with Meredith and Julia, to be in Gottingen alongside Gerhard and his exceptional team and watch the signatures flow from the Roland offset printing machine, matching exactly Chuck Kelton’s silver prints.

My one regret was that Mary Ellen was not there to witness it.

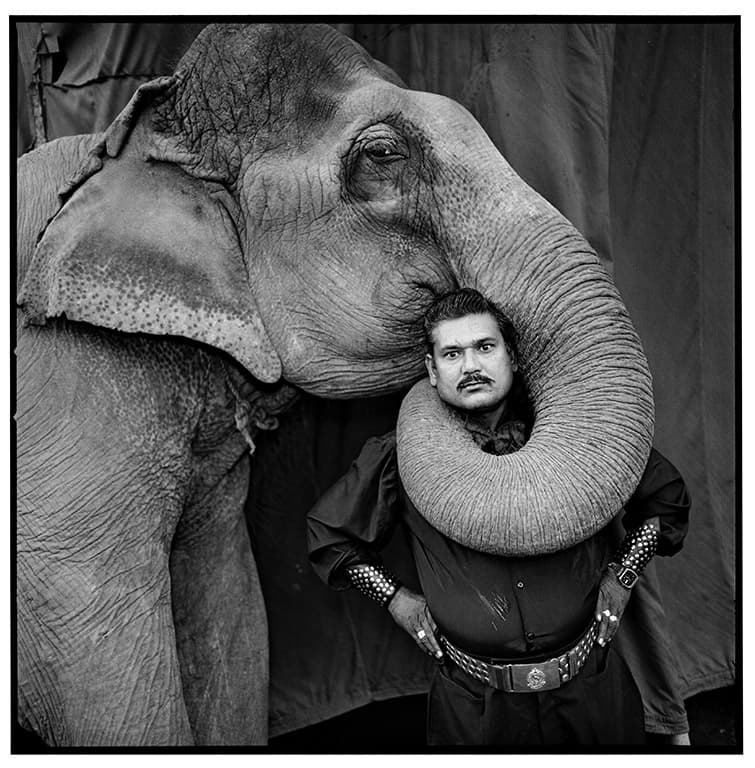

Ram Prakash Singh with his elephant, Shyama, Great Golden Circus. Ahmedabad, India, 1990

Who inspired Mark’s work?

As a child Mary Ellen was moved by an illustrated screenplay, The Forgotten Village by John Steinbeck, which was published in 1941. The illustrations in the book are still frames from that movie and the young Mary Ellen’s imagination was caught up in the story these images told, she thought that the characters were real. They were, in fact, actual villagers cast in a movie.

Mary Ellen worked on two Federico Fellini films: Fellini Satyricon, 1969, and Roma, 1972. Watching this genius creating his unique world with his actors, costume and sets as well as watching his cinematographer lighting the set was an invaluable experience for her.

I think this work resonated with her when many years later she photographed the Indian circus. ‘Mary Ellen would often give her students a list of photographers whose work she admired and wanted them to study. Those that were always on the list were Margaret Bourke-White, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Walker Evans, Josef Koudelka, Dorothea Lange, Helen Levitt, Helmut Newton, Irving Penn, Marion Post Wolcott and Alex Webb.

left: Federico Fellini with a bullhorn during the shooting of Fellini Satyricon, Rome, 1968

What were Mary Ellen Mark’s main motivations for her work? ‘

Mary Ellen said in an interview for Swedish broadcaster SVT in 2010, “I didn’t have the happiest home life or childhood, so I think that gave me a feeling of justice and passion for those people that don’t have

all the breaks. I think it was important to me to be free and wander the world and not have a family. I don’t have kids. I think if you don’t come from a happy home, maybe you don’t want to tie yourself down. I always wanted to be completely free. Even from the time that I was like eight years, seven years old, I remember walking home from grade school thinking, when am I going to get out of here? I’ve got to be free. So, the freedom was always a major thought for me, a major plan.”

I think that this describes some of the underlying forces that moved and informed Mary Ellen in her work.’

One of the key factors in her work is the ability to tell a story in one picture – how do you feel it was achieved?

I was in awe at Mary Ellen’s ability to see a story in the simplest of things… something that you might see in the street and walk by without a thought. Her gift was to be able to bring the diverse elements of a story into a single frame. She called these frames “iconic images”.

To be able to achieve this iconic status is virtually impossible. Mary Ellen was never certain that she had captured a frame, ever. ‘I have been in the room or on the street with Mary Ellen and seen her take what I considered a great frame, and I would often say so. She would always say, “I’m not sure.”

Even while editing her contact sheets she would hand me the marked-up sheets to look at, and I would see a beautiful frame and say so and she would always say, “I’m not sure.” I think she went through her entire life not knowing whether she had taken a great frame, but her record speaks for itself.

Can you tell us more about the creative and practical process Mary Ellen Mark used for shooting her projects?

Every detail of an assignment or personal project was researched and documented. Mary Ellen had an extensive library of photographers’ books. Before a shoot she would often look through these monographs to understand how other photographers had solved problems. She kept notes and research on story ideas she was interested in shooting.

All the studio work was fully documented from the preparation with assistants through to detailed records of lighting – distances of strobes from camera and backdrop, power output for exposure, lenses, f-stops… all these records are now part of the archive.

Did her use of different camera formats change her approach?

‘We have a photograph of Mary Ellen, as a young teenager, holding her Kodak Brownie camera. She shot film her whole life, mainly Tri-X negative and Kodachrome. From the beginning of her career, she used Leica, Canon and Nikon cameras for 35mm film.

In the early ’80s she started using the square format of the Rollei and later the Hasselblad. In the late ’80s the Linhof 4×5 started to be used along with the Mamiya 7, which she enjoyed using on the street.

Mary Ellen had used Polaroid for checking exposures but in the mid-’90s she fell in love with the Polaroid 20×24 camera. This massive camera was employed on two personal book projects, Twins, 2003, and Prom, 2012. Over the years she returned constantly to the Leica with Tri-X film – it was, for her, a true and trusted relationship.

How did she connect with the subjects of her photographs?

Once Mary Ellen photographed you, you were never forgotten. Not you, your children, your pets. Everyone’s name was remembered including the pets, especially dogs. In 1983 Mary Ellen was assigned by LIFE magazine to photograph a story on kids living on the streets of downtown Seattle.

Tiny was one of those kids – that was her street name – her given name was Erin Blackwell, and she was 13. On that LIFE assignment Mary Ellen also met Rat, Mike, Patty and Munchkin, Patrice, Lulu and DeWayne. She called from Seattle and told me of the lives of these kids and said we should make a film with them.

That same year we made the film Streetwise; it was nominated for an Academy Award. For the following 32 years, Mary Ellen went back to Seattle and documented the life of Erin and her growing family of ten children. We made another film using all the material we collected throughout the years working with Erin – Tiny: The Life of Erin Blackwell.’

Did Mary Ellen Mark have a favourite country to work in?

I think India and Mexico would be high on the list. Mary Ellen had travelled in India extensively and made two personal book projects there, Falkland Road and Indian Circus. I think the energy, diversity, and accessibility of the cultures was seductive for her. She taught in Mexico for 20 years.

Most of the work is in black & white… why do you think this was a crucial element of her work?

I think what appealed to Mary Ellen about black & white photography was its abstraction and timelessness.

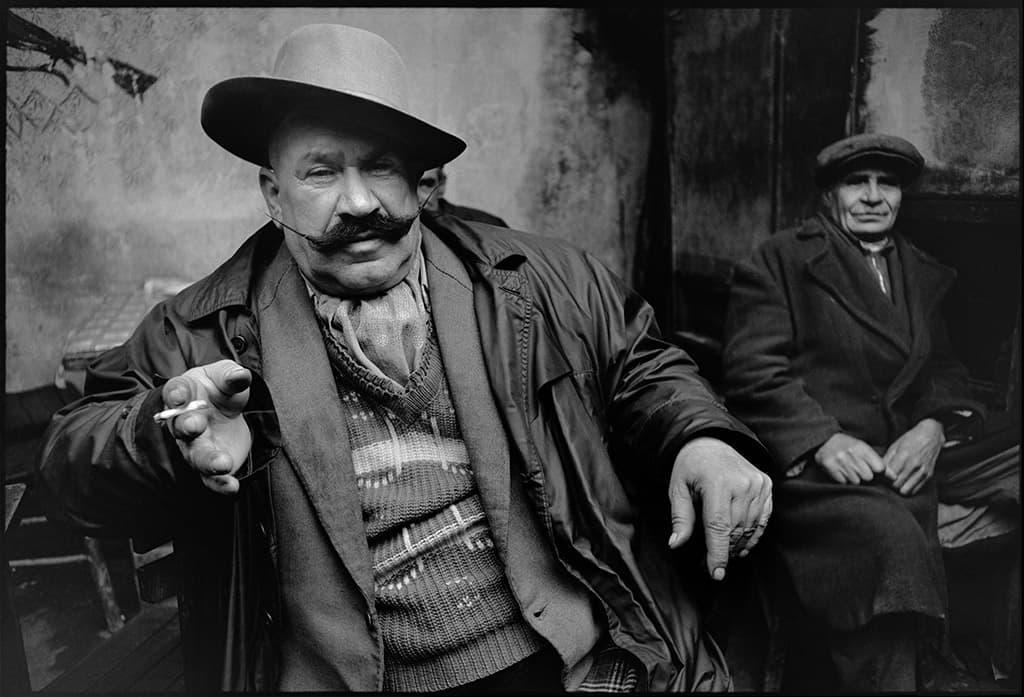

The Man Who Won the Moustache Contest. Istanbul, Turkey, 1965

Did Mary Ellen Mark print much of her work?

A friend of Mary Ellen’s, the photographer Ralph Gibson, told me that he has a print that she made and gave him of ‘The Man Who Won the Moustache Contest’. The image was taken in 1965 while she was working in Turkey. He said that Mary Ellen was a great printer.

She gave up printing in the ’70s when she developed an allergy to the film processing chemistry. Mary Ellen worked with several printers throughout her career though. In 2000 she started working with Chuck Kelton and he printed for her till the end of her life.

Is there anything that Mary Ellen Mark was most proud of, in terms of her career?

I think Mary Ellen took pride in all her work. Her work was her life, and she lived her life to the max.

Do you have any future plans for the Mary Ellen Mark archive?

We are working on publishing an expanded edition of Ward 81 using transcripts from audio recordings made in 1976 when Mary Ellen and Karen Folger Jacobs were working for 36 days on Ward 81, a locked ward for women in the Oregon State Hospital. The audio is a daily log of what they discovered there as well as recordings made by the patients themselves. We discovered the 56 tapes while researching The Book of Everything.

We are also planning to re-publish other projects like Falkland Road and Indian Circus. There are two exhibitions which will open when Covid-19 allows, and we are also in the midst of completely rebuilding Mary Ellen’s website from the ground up.

Mary Ellen Mark

Mary Ellen Mark specialised in documentary, portraiture and advertising work. After getting a degree in painting and art history she did a master’s degree in photojournalism and received a Fulbright Scholarship to photograph in Turkey for year. She moved to New York and began photographing people on the fringes of society.

She was a member of Magnum Photos from 1977 to 1981 and also shot on-set stills on over 100 movies. Mark travelled widely to work and taught workshops in the US and Mexico. She died in 2015 of cancer.

The three-volume The Book of Everything, by Mary Ellen Mark, edited by Martin Bell, is published by Steidl, ISBN: 978-3-95829-565-0, with an RRP of € £125. To find out more go to the publisher’s website.