Professor Newman reflects on the drawbacks of assessing cameras and lenses using simplified metrics

A few years ago I was having coffee with a colleague and he was bemoaning the rejection of his latest paper, which was about compounds his team had developed that were effective against cancerous cells. The referee’s comment was that it should be ‘more quantitative’.

The analysis was based on microscope slides, which showed the concentration of cancer indicative features around the cell nucleus, and the effect was obvious on visual inspection.

The challenge was to provide a figure that indicated the obviousness, and the answer was to invent a metric. I produced an image analysis program which counted the features and plotted their distance from the cell nucleus. The metric was the ratio between the density close to the nucleus and that at a distance. We gave this a name, resubmitted the paper and it was accepted.

In the photographic reviewing industry, the demand for quantitative metrics is strong. They make things easier for both reviewers and readers. Rather than having to make a nuanced and informed assessment, ‘bigger’ can simply be taken to be ‘better’. The problem with metrics is that they tell you something, but it’s not necessarily what you’re interested in knowing.

In photography reviews, two metrics are very popular

Many camera reviews give figures for ‘dynamic range’. This is quite easy to measure from a raw image file: it’s simply the value of the largest value that can occur in the file divided by the noise measured from a patch of black. Take one shot with the lens cap on and one well overexposed, and you have all the information necessary.

But is it actually useful to photographers?

The answer is – to a point. What it doesn’t tell you is how noisy your photos will look, though many people reading the reviews seem to be under that impression. It also doesn’t tell you directly the range of tones that can be reproduced in a final image. Nor does it give you exactly the exposure latitude. Certainly it contributes to the last two, but it is far from the sole factor. It’s a useful metric for people designing cameras, or raw processing software, but less useful to the photographer. Yet buyers will reject a camera because of the dynamic range metric alone.

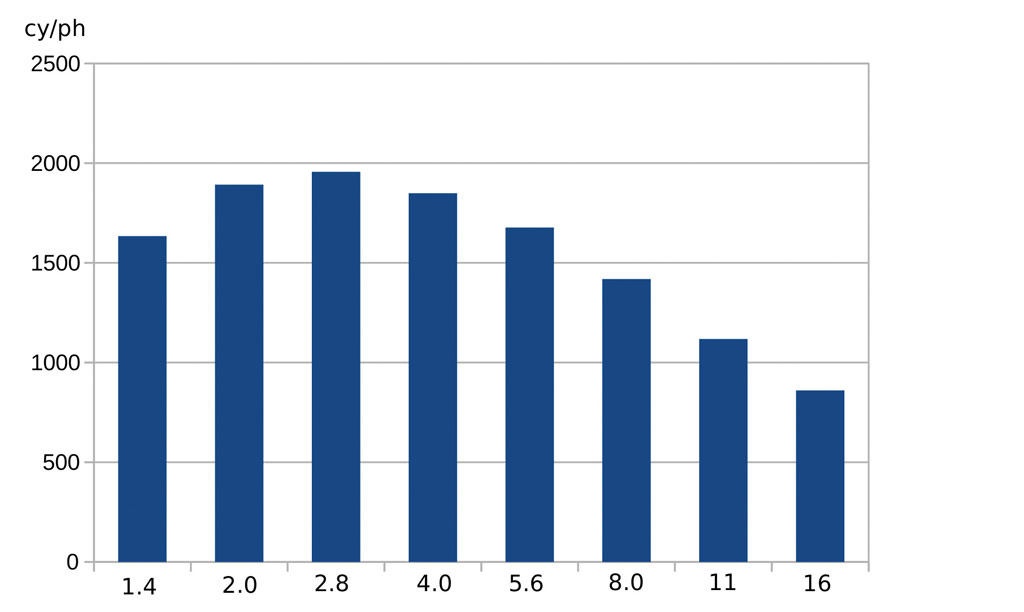

Professor Newman metrics – Here’s what an MTF50 chart might look like, with aperture settings along the bottom.

The second popular metric is ‘MTF50’ applied to lens tests. This is used because it produces similar results to the ‘line pairs per millimetre’ tests that were the mainstay of lens testing for decades.

These were produced by photographing test charts with black and white grids of ever decreasing size. The size at which the bars in the grids were just visually separable became the ‘resolution’ of the lens. But this was dependent on the visual acuity of the tester, and also the means used to view it; either via enlarged prints, or the negative placed under a microscope.

MTF, or ‘modulus transfer function’ is determined by photographing a ‘slanted edge’ from which a program can calculate the spatial frequency response of the lens.

There is a great deal of information to be had from the overall MTF, but the bit used in lens reviews is typically MTF50, the spatial frequency at which the lens gives a contrast of 50%. The theory is that the higher the frequency the better the lens.

The problem is though that MTF50 has not that great a correlation with what a viewer would perceive as ‘sharpness’, which is why lens makers typically don’t use it.

Bob Newman is currently Professor of Computer Science at the University of Wolverhampton. He has been working with the design and development of high-technology equipment for 35 years and two of his products have won innovation awards. Bob is also a camera nut and a keen amateur photographer.

The views expressed in this column are not necessarily those of Amateur Photographer magazine or Kelsey Media Limited. If you have an opinion you’d like to share on this topic, or any other photography related subject, email: [email protected].

Related reading:

- Opinion: why the Voigtländer 50mm f/1.0 Nokton lens is so special

- How much resolution do you actually NEED?

- Tim Coleman on Gear Acquisition Syndrome (GAS)

- Jon Bentley: Pixels vs Noise – Are bigger pixels better?