Cameras, indeed, do not lie. Photographers, on the other hand, are given to using their cameras, their darkrooms, their retouching pencils and their software applications to enhance what they saw. We’ve been doing it for a hundred years, and to a certain degree it’s expected. No subject wants to know what they really look like, after all, and you wouldn’t be forgiven by a bride, or any portrait sitter, if you didn’t remove that too-much-pizza forehead pimple.

Even before the recent rise in public consciousness of the part played by Artificial Intelligence in bringing humanity to its knees, manipulated images have been used to engineer public opinion, to fake nudes of celebrities, and demonstrate alternative facts about what really happened. In some cases this can be harmless fun, but in others it can have serious consequences both for those believing the images, and for those depicted in them.

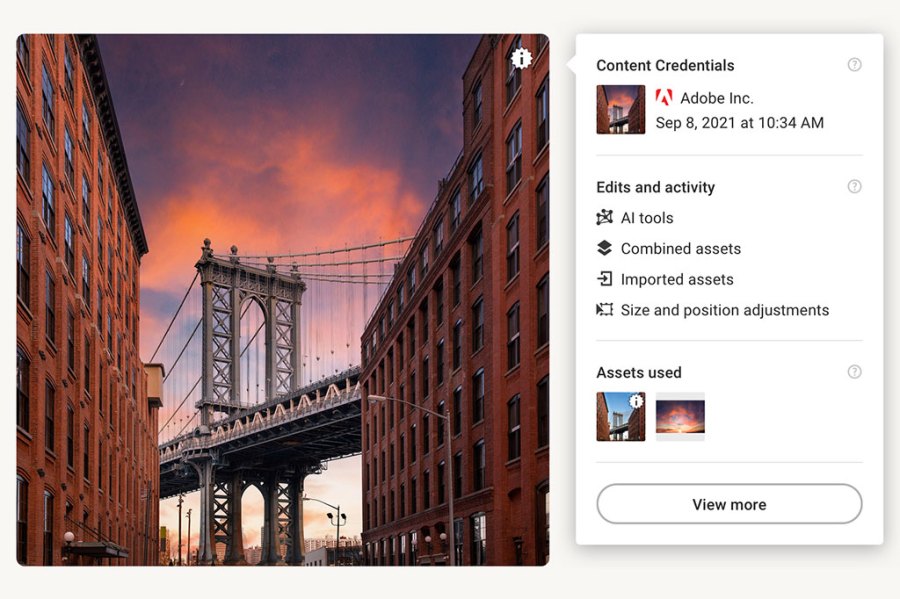

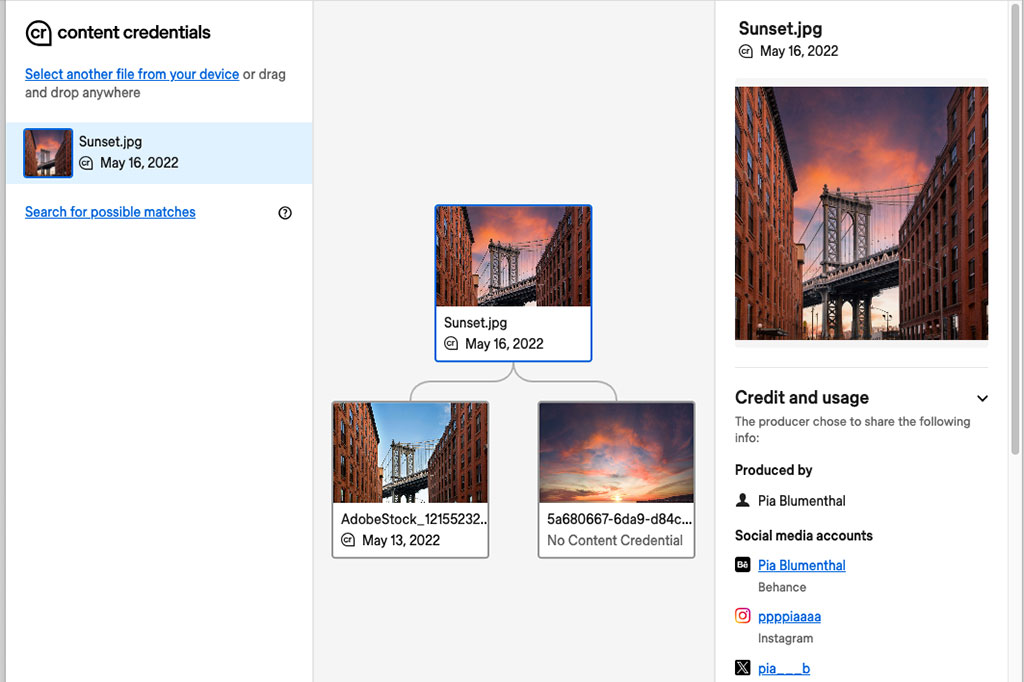

Leica’s new M11-P, with its Content Credentials feature, is the first full production camera we have seen that offers a serious means for anyone to trace where a picture came from and what it actually looked like when it was taken. It is of course one thing to have this feature in a camera, but another to offer the means for viewers to easily check those credentials. For this to happen we need social media platforms and web browsers to support the standard, as this is where most people will encounter images that need to be checked. And we need a situation in which it is unusual for a ‘this happened’ image not to have credentials; otherwise, folk will continue to believe what they are shown.

In the professional documentary and news sector, I can see that the need for images with credentials will catch on. Picture editors will be able to check the authenticity of an image before they publish it, so consumers of such publications will be able to have faith that images show what happened in the way that it happened. I think we all have faith in the images we see in most printed newspapers in this country, but this system will allow the same faith to be applied to online publications with which we are less familiar.

Photographers need this system too, as it will allow them to prove more easily when their images have been tampered with, or when elements have been stolen to be used in another picture. Even when the thief has stripped out the data it will be possible to match the pinched image with a copy of the original saved on an online database, and to re-apply the original credentials.

Content Credentials aims to allow anyone to check how an image has been created using publicly available tools.

However, the whole system depends on people using it. Crucially, it needs to become the norm in the sorts of situations in which we need to know where an image has come from. For the enthusiast, it’s possible some competitions might come to require it, so Barry at the camera club might not get away with his amazing wildlife coincidences any more.

But the Content Credentials system isn’t about stopping manipulations, or condemning the stripping-in of a better sky or making a portrait sitter look a bit slimmer. It’s about making sure that when a picture is fiddled with, we know, so no one gets the wrong idea and so we can really believe what we see. There’s a long way to go, of course, but perhaps these first steps will lead us somewhere worthwhile.

The views expressed in this column are not necessarily those of Amateur Photographer magazine or Kelsey Media Limited. If you have an opinion you’d like to share on this topic, or any other photography-related subject, email: [email protected]

Follow AP on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube.