An exhibition that claims to explore the relationship between painting and photography fails to deliver on its promise, says Tracy Calder. However, if you like great art and you’re willing to ignore the brief, you’re in for a treat

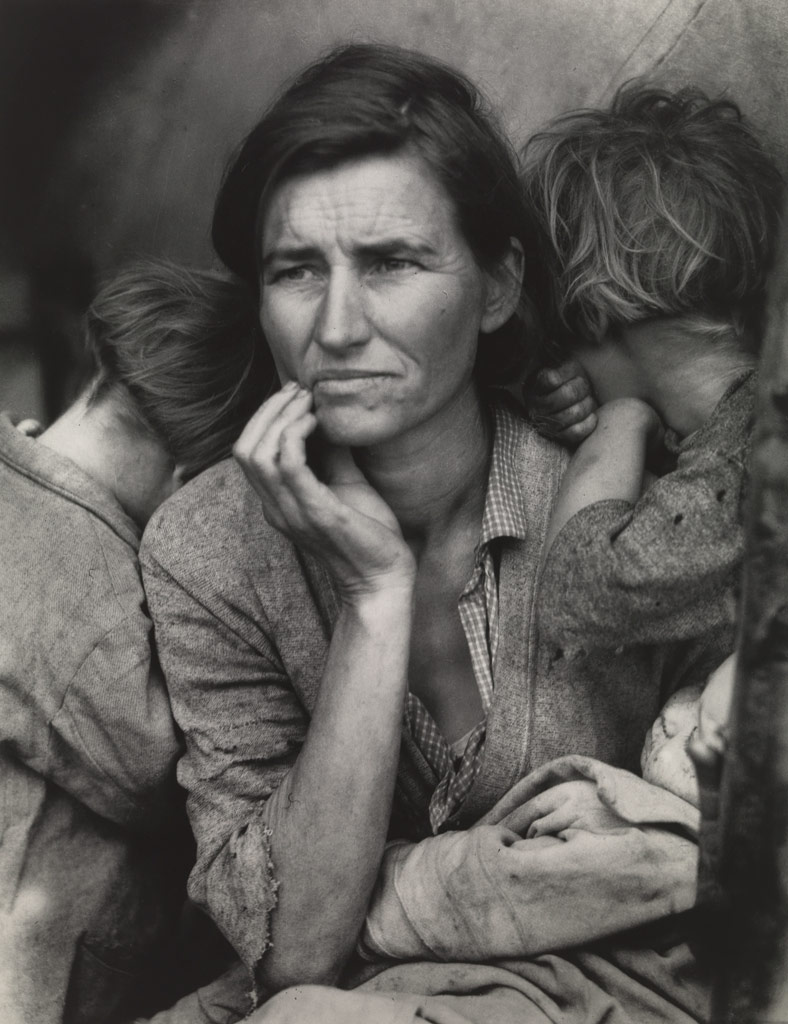

Back in July, I found myself alone in a cavernous room staring at Dorothea Lange’s portrait of Florence Thompson (more commonly known as ‘Migrant Mother’). Like most people, I’ve seen this picture many times in books, newspapers and magazines, so when I occasionally see it in a gallery, I’m bringing a fair amount of knowledge (and personal feeling) to the viewing experience. Lange spotted Thompson in a pea-pickers camp in Nipomo, California, in 1936 and felt compelled to photograph her as she sheltered in a makeshift tent. ‘I saw and approached the hungry and desperate mother, as if drawn by a magnet,’ she revealed in Popular Photography magazine in 1960.

Thompson and her sizeable brood are said to have been surviving on frozen vegetables and birds foraged from the fields surrounding the camp. Lange was working for what would later be called the Farm Security Administration, an agency set up to support farm workers during the Great Depression. What I didn’t know, was that the photographer apparently promised Thompson a print, which she never delivered, and, according to the editor of The Modesto Bee newspaper, the labourer wished the shot had never been taken.

The threat of photography

It was an unexpected joy to have the gallery to myself, but at this point I couldn’t quite fathom why Tate Modern’s latest show, Capturing the Moment, was so deathly quiet. Sure, it was up against the behemoth painter Piet Mondrian (and Hilma AF Klint) in neighbouring galleries, but with work by Andreas Gursky, Candida Höfer and Hiroshi Sugimoto given space, it should have been positively heaving. Turning to the second wall I came face-to-face with one of Picasso’s ‘Weeping Woman’ paintings. A shiver ran down my spine as, again, I realised I was alone with a staggeringly good piece of art.

Moving in close I could really see the texture of the paint – it has been applied quickly, urgently, as though the painter is trying to capture one feeling before it mutates into another. To link the painting to the theme, the show guide (there is no catalogue) says, ‘He [Picasso] collapses multiple perspectives into one single moment in time.’ Unlike many of his contemporaries, Picasso didn’t feel threatened by photography and, if anything, he used its popularity as an excuse to explore the unique properties of his favoured medium. ‘Photography has arrived at a point where it is capable of liberating painting from all literature, from the anecdote, and even from the subject,’ he declared. ‘So shouldn’t painters profit from their newly acquired liberty to do other things?’

Feelings of confusion

Picasso’s ‘Weeping Woman’ (and a few of his lesser-known portraits) hangs alongside paintings from Alice Neel, Lucien Freud and Francis Bacon in Room 1 (Painting in the Time of Photography). Bacon used photographs as source material for some of his paintings but sadly, none of those appear here. Where you might expect to see a cabinet of artist’s books and behind-the scenes notes, there is, well, nothing. I began to feel uneasy. The promotional literature promised an exploration of the relationship between painting and photography, Tate has an extensive collection of both (and the pulling power to borrow what it likes), so why did the work in this room feel so disjointed?

The confusion continued as I walked into Room 2 (Tensions). Here I was met with fabulous paintings by Cecily Brown, George Baselitz, Paula Rego among others, intended to show how paint on a canvas can be used to convey the raw essence of bodies or figures. ‘Material, expressive painting such as this resists the precision of the mechanical eye and a world increasingly filled with photographic imagery,’ offered the guide. And herein lies the problem: at times the relationship between some of the artwork in the show needs explaining because, frankly, the link is pretty tenuous. But when an explanation is offered up, it’s often too simplistic. In fact, at times it feels like the curators even know this – the intro text states, ‘Rather than attempt a definitive account of the dialogue between the two media, an open-ended discussion is encouraged.’

Viewing Dorothea Lange’s ‘Migrant Mother’. Capturing the Moment Installation View, Tate Modern 2023

Stonkingly good art

There can be no disputing this show contains some stonkingly good art. Room 3 is entirely given over to Jeff Wall’s image, ‘A Sudden Gust of Wind (after Hokusai)’, which, considering the technology available to him at the time (1993) still looks remarkably good on a lightbox. The photograph (based on a woodcut by Japanese painter Katsushika Hokusai) took more than a year to complete and comprises over 100 images. Here the link between photography and painting is obvious. (Wall trained as a painter and admits that he is indebted to historic art, in particular ‘tableau’ paintings.) It was great to see the original study for the artwork included in all its papery, sketchy glory.

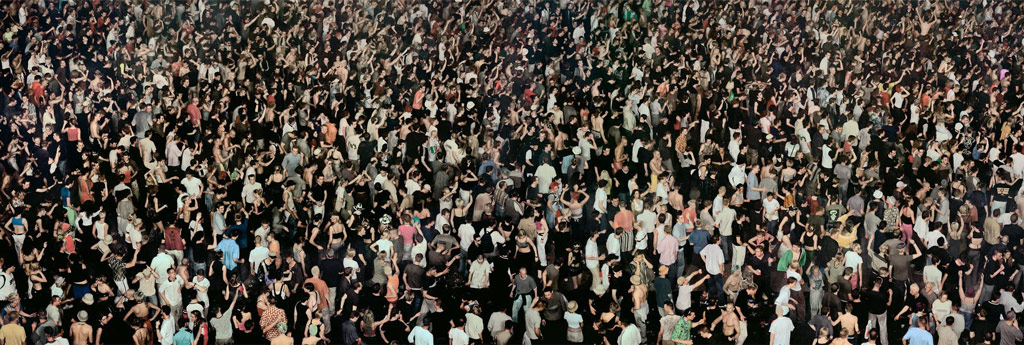

Rooms 4 and 5 were a real highlight as they contain artwork by some of my favourite photographers: Andreas Gursky, Hiroshi Sugimoto and Candida Höfer. Once more I looked around in disbelief – a few years ago I had to elbow my way to the front of a crowd looking at Gursky’s image ‘The Rhine II’ and yet here I was admiring some of his work entirely alone. Sugimoto’s abstract seascapes always bewitch me and the examples in Room 5 are no different. To my mind, the work in these two rooms answers the brief perfectly – although the guide does its best to muddy the waters.

Gaining extra gravitas

Perhaps the greatest surprise was the feeling I experienced in Room 6 (Capturing History). I’ve always been aware of Gerhard Richter’s photo paintings but seeing them in the flesh was unexpectedly moving. Richter’s painting, ‘Two Candles’, is peaceful and meditative, but at the same time it encourages us to think about the transience of life. ‘[It] adopts the still-life tradition of memento mori – a reminder of death,’ echoes the guide.

Richter’s haunting work, ‘Tante Marianne’, is even more striking. This painting shows the artist as a young boy sitting on his aunt’s lap. The photograph the painting is based on was taken in 1932. Six years later, Marianne – who was living with schizophrenia – was forcibly sterilised. In the final months of WWII, she was taken to a psychiatric hospital by the Nazis and starved to death. Richter says he was unaware of the cruelty his aunt was subjected to when he made the painting in 1965 – if this is the case, then the artwork gains extra gravitas due to this new context.

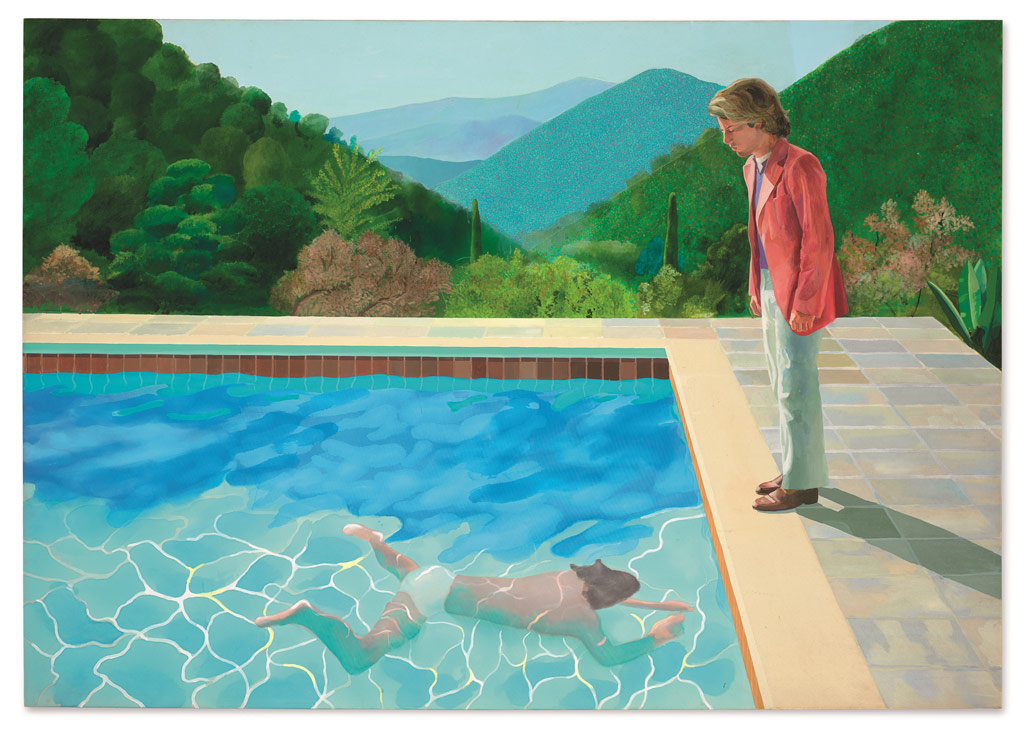

Room 7 (Convergence) looks at how photography has been employed in Pop art, and it was great to see big guns such as Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg and Pauline Boty represented. Any excuse to see David Hockney’s painting, ‘Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man’, is fine by me, so I was delighted to find it here (although I would rather it had been given its own room). However, without the photos that inspired the work it feels unmoored. In fact, this room with its mixture of fantastical, cinematic and occasionally disquieting images is, arguably, the least cohesive. The work is thought-provoking, for sure, but the attachment to the brief is threadbare.

David Hockney. ‘Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures)’, 1972. YAGEO Foundation Collection, Taiwan

Looking to the future

The show concludes with a dismissively brief look at ‘the visual and emotional possibilities of painting in the digital age.’ This idea could fill all eight galleries by itself, so maybe it’s unfair to expect anything too comprehensive. (Despite its shortcomings, on display are notable works by Laura Owens, Lorna Simpson and Salman Toor.)

The reason Capturing the Moment suffers from so many highs and lows is obvious if you read the intro text: most of the work has been borrowed from the YAGEO Foundation, headed up by collector, entrepreneur and philanthropist Pierre Chen. While it’s great to see such quality privately-owned work on public display it’s hard not to view this as a missed opportunity. The narrative running through the show is disjointed and, at times, confusing. There’s a section in the middle where it seems to find its feet, but then, sadly, loses its way again.

Maybe it would’ve been better to focus on Chen’s art collection and market the show as a celebration of great taste (and great financial freedom) rather than label it as an exploration of the relationship between photography and painting.

Heading towards the exit I wondered if Tate Modern might eventually host a comprehensive exploration of the relationship between the two mediums, or if it feels it’s had its fingers burned here. If it ever feels brave enough to have a second try, I will be first in line for a ticket.

The views expressed in this column are not necessarily those of Amateur Photographer magazine or Kelsey Media Limited. If you have an opinion you’d like to share on this topic, or any other photography-related subject, email: [email protected]

Related reading:

- Best photography exhibitions to see

- Tate Modern to show classic surrealist photographs

- Robert Doisneau: Life beyond the world famous kiss

Follow AP on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube and TikTok.