Impossible’s HQ in Berlin, Germany

In a world dominated by digital imaging, the death of the iconic Polaroid company was perhaps an inevitability. Instant film couldn’t compete with the immediacy of digital and, in 2008, Polaroid finally ended production. The future for instant analogue film – once a fixture in every professional studio – looked grim.

While there was enough stockpiled to keep enthusiasts supplied for a while, without a new source of film it appeared instant analogue products were to be consigned to the history books. But even as Polaroid shut its doors, two visionaries were cooking up plans to keep the format alive.

Florian ‘Doc’ Kaps and André Bosman raised enough investment to purchase the final factory making instant film and set about creating a company that would, against all odds, keep the process alive. It was a huge gamble, a fact reflected in the name of their company – The Impossible Project (also influenced by Polaroid mastermind Edwin H Land’s quote: ‘Don’t do anything that someone else can do. Don’t undertake a project unless it is manifestly important and nearly impossible’).

This month, The Impossible Project celebrates its sixth birthday and, while current Chief Executive Officer Creed O’Hanlon and Chief Operating and Technical Officer Stephen Herchen aren’t declaring The Impossible Project is yet complete, they are agreed it has survived some difficult times and the future is now looking more positive than ever.

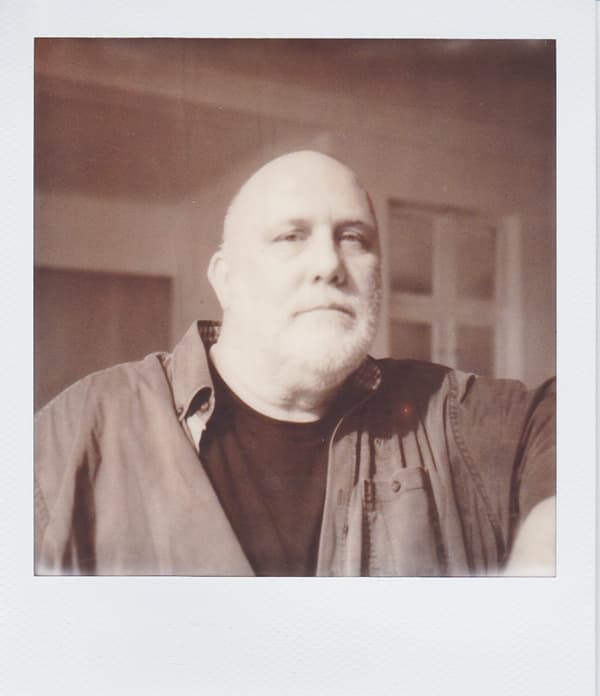

Creed O’Hanlon

Undoubtedly, The Impossible Project has experienced a roller-coaster ride since its launch. While the passion and dedication of the founders and the team they recruited ensured that new, instant films were launched and many classic Polaroid cameras were refurbished, it has not been an easy existence. Despite raising $559,000 in a successful Kickstarter campaign, the business was still lacking serious investment and a structure to really move it forward. It was against this backdrop that O’Hanlon, whose background was in both analogue and digital media, entered the fray.

‘At the beginning of 2013, the company was undergoing some changes and Doc (Kaps) was looking at restructuring the senior management,’ explains Creed. ‘He invited me to Berlin to look at the e-commerce strategy but, on my way home to south-west France, I was called and asked to take over as CEO. My wife said ‘no’ because we were enjoying a pleasant semi-retired life then, but I said yes!’

Creed saw the potential of the project, but was immediately struck by some of the problems it faced. So he centralised the business’s front end functions in Berlin, shut some overseas offices, scaled down others and took a cold, hard look at the quality of the film it was producing.

‘I had to bring some business expertise to proceedings. It was a big sprawling company and it needed rationalising,’ Creed adds. ‘In 2012, only 10% of the customers buying our film were re-buying them. Clearly, we had some issues and I even stopped production for six weeks because of it,’ he admits.

Test shots of London’s iconic Shard

Mining history

Central to Creed’s vision for the company was tapping into the knowledge of Polaroid’s past. This is what led him to Stephen Herchen. Having worked for Polaroid for 28 years, Stephen provided the direct link between The Impossible Project and the original Polaroid processes.

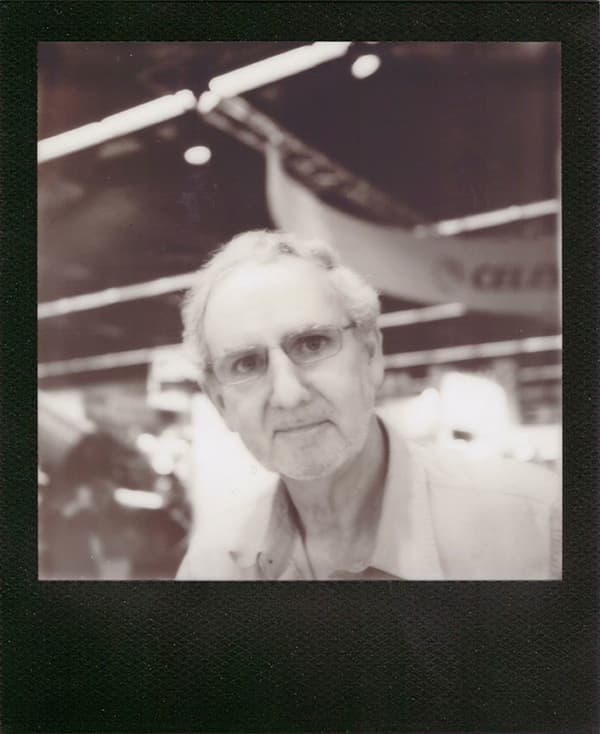

Stephen Herchen

‘Stephen came to give us some advice but fell in love with the format all over again,’ Creed reveals. ‘His direct involvement was a huge turning point for us, and evidence of his influence on the company is the quality of film we are producing now. The next release will be even better, and certainly the point when we start to equal the products created by Polaroid itself.’

Stephen’s eye as the chief technical officer is clearly fixed on further product improvement. ‘I think what I’ve been able to do is still taking shape. It’s not come to fruition yet. We are looking at the chemistry of the product – seeing what we are doing well and what the shortcomings are,’ he says.

The creation of a computer model that enables them to simulate the components before they are actually worked on is a huge step forward.

‘It allows us to see exactly what we can do to make the biggest improvements and then focus our time into developing the right areas,’ reveals Stephen.

The actual process of creating instant analogue film is incredibly complex, and Stephen makes it very clear that he believes it is the world’s most chemically complex man-made product.

He acknowledges that there has been a dramatic improvement in the quality of the company’s film from a year ago, but is quick to put the credit for this on the team that was working on it before his knowledge was added to the mix. But in terms of where future improvements lie, he is very clear in his predictions.

‘We will see colour instant film improved in terms of its ‘instantness’ and quality. We are hoping that the first half of next year will see a big step change. Then, as we get to the end of the year, I think we will be able to move it forward yet again.’

The speed at which an image is developed is a key part of the process, and Stephen predicts that a colour film that currently takes eight to ten minutes to reveal an image and 40 minutes to finish its development will be cut to two minutes and 30 minutes initially, before being pushed down to as little as ten minutes for a developed print.

Countless test shots are produced in order to further product development and quality

Fresh eyes

Both Creed and Stephen agree that their consumer base is changing as rapidly as they are attempting to develop the products. While they know they have a die-hard group of analogue lovers who have never stopped using instant film, or at least returned to it as soon as it was readily available again, they recognise an emerging group of younger users.

‘These people have a genuine desire for the physicality of our products,’ explains Creed. ‘Our Instant Lab means that you can produce a print in that iconic square format from your phone. Teenagers are experiencing that magic of watching a film emerge. That complex chemical reaction that results in something tangible is driving this fascination.’

Stephen admits that his dedication to the task at hand is driven through passion. ‘I love what The Impossible Project is trying to do here and, as I’ve already dedicated 28 years of my life to this process, it has become part of my DNA,’ he explains. ‘When Polaroid was winding down it was a difficult time, but this is keeping it alive for older and younger users.’

Having met so many photographers of all ages who are passionate about the process, he describes what he does as an ‘incredible joy’.

With improving film products and even a new camera on the horizon, the management team at The Impossible Project has reason to be optimistic about the future of its analogue products.

‘Making instant analogue film is a hand-made process,’ Creed sums up. ‘It is more akin to making fine wine, and so there will always be an element of project about what we do. But we are working hard to create the right professional structure.

‘It was never a career move for me; I was simply fascinated by what had been achieved and then interested in how I could help turn it into a profitable, long-term venture.’

Jos Ridderhof renovating and reparing a Polaroid SX-70 camera

Jos is one of the few remaining experts who can recondition old Polaroid cameras

The SX-70

The National Media Museum’s Colin Harding looks back at Polaroid’s iconic SX-70 camera

Of all the cameras produced by Polaroid it will always be the SX-70 produced in 1972 that will forever be synonymous with instant images.

The first generation of Polaroid cameras produced monochrome images and operated using the peel-apart system. After exposure, the photographer would pull the exposed film out of the camera and the action would burst the pod of chemicals, which would spread across the image.

In 1972, Polaroid introduced the first folding camera: the SX-70, and developed the first integral pack containing the film, chemicals and battery. After exposure, the camera automatically ejected the image, the action of which spread the chemicals across the image and initiated development. Within a year, Polaroid was producing 5,000 SX-70 models a day. Perhaps the introduction of this camera is largely responsible for the fact that, in 1974, it was estimated that around a billion Polaroids had been taken.

The history of Polaroid

1926: Harvard drop-out Edwin H Land pursues work on light polarisation. Two years later, he files the patent for the first synthetic polariser.

1937: The Polaroid Corporation is formed. The company makes glasses, ski goggles, stereoscopic motion picture viewers and many other products.

1943: Land conceives the one-step photographic system when his daughter asks why she can’t see the picture he has just taken of her.

1947: Land reveals the one-step process at the Optical Society of America. In 1948, the Model 95 Land camera is launched. Sales exceed $5 million in one year.

1961: Polaroid Positive/Negative 4x5in film Type 55 is introduced – the first black & white film producing a positive and a negative. Two years later, Polaroid introduces Type 38 and 48, its first instant colour films. The Model 100 Land camera is launched.

1965: Polaroid debuts the $20 Swinger, a plastic-cased camera that takes only black & white wallet-sized photographs.

1971: The Big Shot Land camera debuts, designed to take flash colour portraits. Andy Warhol becomes its best-known user.

1972: The Polaroid SX-70 Land camera arrives. The first fully automatic, motorised, folding SLR ejecting self-developing colour prints.

1976: Sales of Polaroid cameras exceed six million units. A year later, the OneStep Land camera, an inexpensive fixed-focus becomes the best-selling camera in the US.

1980: Edwin Land retires as CEO. Three years later, the company has 13,402 employees, $1.3 billion in sales and over 1,000 patents.

1985: Polaroid’s legal victory in a long- running dispute forces Kodak out of the instant-camera business.

1991: Polaroid founder Edwin H Land dies on March 1. In 1992, the ultra-compact Captiva camera and film system (portraits) is launched.

1998: Polaroid corners the instant- image market again by becoming number one digital camera seller in the US.

2001: Over seven years, Polaroid faces financial challenges making the transition from analogue to digital. The company files for bankruptcy and stops instant-film production.

2008: The founders of The Impossible Project purchase the last factory in the world manufacturing Polaroid instant film.

2009: The Polaroid brand is purchased by PLR IP Holdings, LLC, and produces the PoGo Instant Digital Camera and more.

2010: The Project begins production of its own reformulated versions of classic Polaroid instant film for vintage cameras.

For more information visit www.the-impossible-project.com

See also: Instant: The Story of Polaroid