Photographer and educator Arteh Odjidja has been photographing and interviewing young migrants and refugees for his book, Fear & Dreams: The Stranger Series. Peter Dench finds out more…

In 2012, when London-born photographer Arteh Odjidja was visiting Moscow for an Ozwald Boateng fashion show, he met a young African man called Abdulay who had settled in the Russian capital (via Portugal) after migrating from the West African island of São Tomé and Príncipe.

Odjidja explains, ‘When in Russia, and an obvious foreigner, many people make you feel like you’re a stranger. People literally stare at you and your mind fills in the blanks as to what they’re thinking. You feel like that a lot and I said to myself, if I’ve been here three days and feel like this, what must it be like for Abdulay who’s lived here for two years? That’s when I dived into his story.’

Abdulay. © Arteh Odjidja

Galvanised by his meeting with Abdulay, and disturbed by the sweeping headlines in the media describing migrants entering Europe as swarms, on his return to the UK, Odjidja started paying more attention to migration.

His decision was to create a project to humanise migrants and their individual experiences. ‘I saw these people almost as superheroes. People who migrate, leave everything behind and take that chance on themselves and go and learn a new language, start in a new place, that takes guts.’

Coram Young Citizens workshops

In 2018 Odjidja partnered with Coram Young Citizens. Over a series of workshops, he supported the Young Citizens ambassadors to develop their photography skills and creative voices. The photographs produced showcase the achievements and aspirations of young migrants, challenge public perceptions and inspire those from similar backgrounds.

Over 1,000 people viewed the photographs at venues including British Museum, and City Hall. They were also presented to Her Majesty The Queen at the opening of Coram’s QEII Centre. Some of the young people Odjidja met through the programme are featured in his book; others he met through connections, friends, church and chance encounters.

Odjidja deliberately chose portraiture as his preferred method to deliver the migrants’ stories. A single portrait to counter media images of the masses. Using a stripped back approach of a hand-held Leica allowed him to employ many of his other skills.

Ramin. © Arteh Odjidja

He explains, ‘As a photographer you’re not just a camera operator, you’re a conversationalist, body language expert, friend, mentor, organiser, inspirer – all these things you need to get the image that you want from that person. It’s about being a human being in that moment and saying I need to connect with your humanity. Having a smaller kit for me was having no barrier to that. The camera was often incidental.’

Odjidja’s portraits took him across the UK, to Moscow, Russia and Berlin, Germany. After conversations with his subjects, locations relevant to the individual’s story would be discussed and decided, making sure they got to present themselves how they wanted to be seen.

Youth Football Coach Ramin Keshavarz, who immigrated to London from Iran in 2008 when he was 17-years-old, is photographed outside Wembley Stadium (above). The 32-year-old classical violinist Ramona Racovicean, is pictured outside City Hall performing to an invisible audience (below).

Ramona. © Arteh Odjidja

Vulnerability & thoughtfulness

Odjidja reveals, ‘I like to capture a bit of vulnerability or thoughtfulness in the imagery which immediately connects with every human being because we all have those moments. I love getting to know people. For me to educate myself, portraiture was a way for an hour or two, to hold that person’s focus. When you’re doing a portrait and it’s just you and them, people are very honest. They trust you if you make them feel comfortable, they do what you want them to do. That trust should never be abused. I want to present these people as individuals.’

Looking through the 20 black-and-white portrait stories in the book, you don’t picture a horde of ragged refugees or a packed boat landing on a beach, you see a portraits of Omar, Fatma, Dami and Joudy. Each face is an introduction to the compelling and diverse first-hand accounts that accompany each portrait.

We learn that Abdulay stayed in Moscow for seven years, met and married Christina from Bulgaria and had a son, Martin. They all now live in Sofia. Bulgarian is Abdulay’s sixth spoken language. We learn that Sayed immigrated to Berlin, Germany when he was 20-years-old after being hit repeatedly over nine days with cables, sticks and guns by the Taliban who wanted to extract information he didn’t have. I won’t disclose any more of the stories as the discovery is part of the appeal of Odjidja’s book.

Rakiba. © Arteh Odjidja

All bar one of the people Odjidja chose to profile are deliberately under 30-years-old. ‘I like hanging out with young people and understanding their dreams. It was an inclination to tell their side of it. We don’t hear young migrant stories as often. They migrate and have to continue their education, learn a new system, a new language in many cases, manage trauma, find a peer group along with everything else. I was interested in that experience, that vulnerability, the peer pressure they face and learning a new way of being here.’

He adds, ‘A lot of people I spoke to were being refused from schools for being perceived as not being at the right literacy and comprehension level. Some of them were so determined to break through these limitations they persuaded people to mentor them and wouldn’t stop until they achieved their goals. I found it really inspiring at that age to have such grit and determination to improve your life and navigate how you do that.’

Omar. © Arteh Odjidja

Choosing to do a book

The story of immigration across Europe will remain and evolve. If the portraits and testimonies of Odjidja’s subjects were published in a magazine or on a website, the awareness would arguably be more temporary, but he had an inclination and an itch to create a book.

‘One thing I discovered early in my career when I was doing a lot of fashion photography was that initial recognition for your work was great, but I didn’t actually like the transience of fashion photography; how temporary it was. Creating a project that you believe in, collecting the thoughts of others is also a testament to your focus and what you want to share with the world. A book is a way to create a sense of permanence about the topic and meaning of what you’re trying to convey. I can give it to people who will cherish it and take the time to look through it. I don’t expect people to read the stories straight away. Maybe in about a year’s time they’ll realise they might want to read them.’

The route into book publishing wasn’t familiar to Odjidja and he quickly became a student of the format. He joined The Photobook Club on Facebook and sourced advice from those in and beyond the industry that he trusted. The feedback was a firehose of information, a lot to take in at once.

He reveals, ‘Creating a book is not like doing an exhibition, you have to take so many more elements into account. The context of enjoying a book is different from an exhibition space, or reading something in a magazine. Understanding and designing an experience for each format is key. It was a growth moment. I evolved from watching and listening to other artists.’

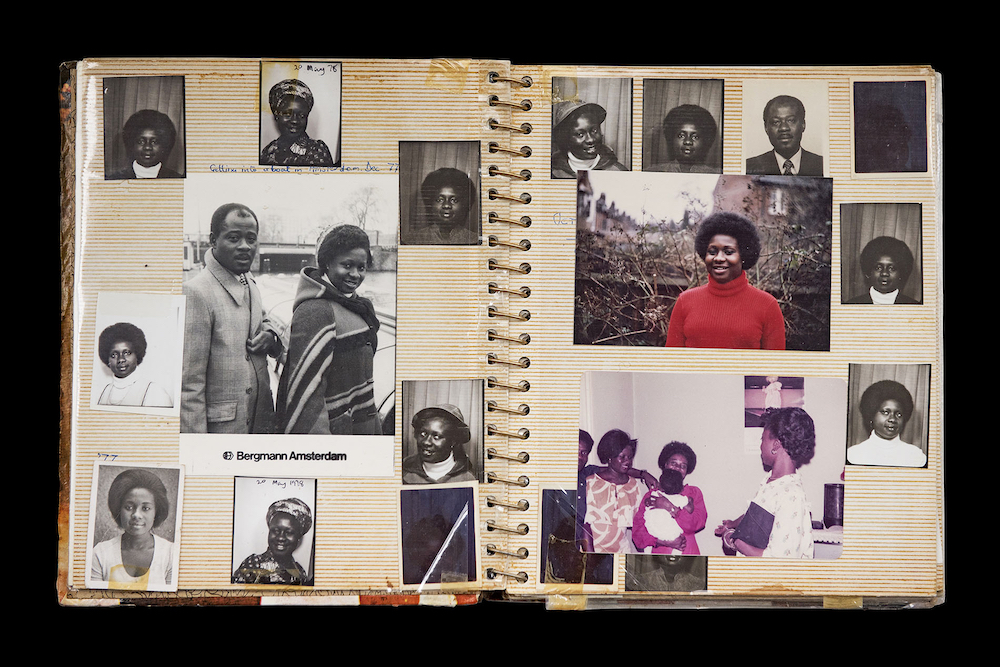

Arteh Odjidja, ‘My parents early photos in their migration to Europe’

Migrating from Ghana

In the early 1980s, Odjidja’s parents migrated to London from Accra, Ghana. Initially, when creating his Stranger Series project, their story didn’t inform what he was doing but he later realised that, of course, it did.

‘My story of migration is my parents’ story of migration and understanding them more is how I relate to every person in the book. It didn’t dawn on me until years into the project. My father and I didn’t always have the closest relationship. The fact that he was unwell and in bed and in one place, and I was older and less judgmental meant I could appreciate him a lot more. Throughout 2018 and 2019, every fortnight I would go and sit by his bed and say we need to do our family history. He was quite coherent and articulate and took me through his life history. Family history is a big part of my faith. A year into doing that he lost the ability to speak, so instead of interviewing him I would just sit with him. I continued by interviewing mum and his work colleagues.’

Odjidja’s father Bernard passed away last year after a decade long illness; his words are preserved at the beginning of the book alongside family photographs.

The Stranger Series: Fear & Dreams is as individual as the people it portrays. Through portraits and testimonies, it helps understand the complexities of the push of oppression and the pull of prosperity that compel so many to cross borders and seek new places to belong. Odjidja’s book journey is currently raising funds on the crowdfund platform Kickstarter. With not long to go, he’s over halfway there.

Khalil. © Arteh Odjidja

Find out more…

To discover more about Arteh Odjidja’s Kickstarter book campaign just visit Kickstarter: Fear and Dreams: The Stranger Series photobook

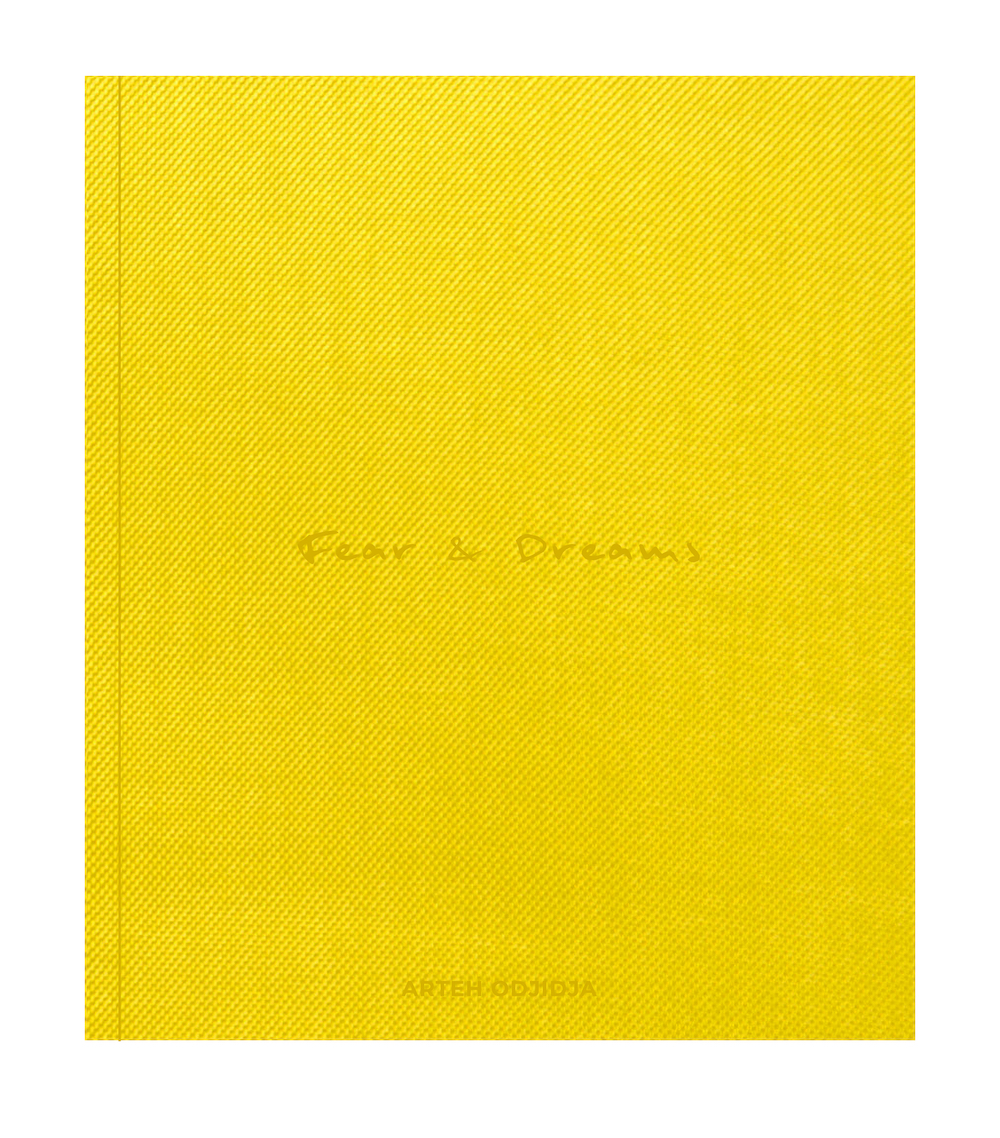

A mock-up of the front cover of Fear & Dreams

Arteh Odjidja

Arteh Odjidja portrait. © Josh Jones

Arteh Odjidja is an award-winning photographer and educator who specialises in portraiture and fine art photography. He has spoken about and exhibited his work across the UK and US. He has drawn much of the inspiration for his work from his West African heritage. Growing up with a father who worked in the filmmaking industry instilled an early fascination with the creative process in him. He has been commissioned by top brands, including Christian Dior, Paul Smith, Ozwald Boateng Savile Row, Montblanc and Oxfam UK. He is also an Akademie ambassador for Leica. His projects aim to challenge our sense of privilege and equality in a transient, fast-paced, modern socio-economic world. His work has been exhibited in prominent galleries like the Tate Modern, The British Museum, City Hall and The Museum of Contemporary Photography (Chicago).

Further reading:

Innovative migrant self-portraits win Sony World Photography 2022 Awards

Casey Orr Saturday Girl: bold portraits exploring identity

Pauline Petit’s surreal portraits