Black Brits have been fighting in Britain’s armed services for a lot longer than most people think. For example around 1000 black British sailors fought in the British Navy with Lord Nelson at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, a battle which cost Nelson his life but established British naval supremacy for over a century. But as we prepare, once again, to remember the millions who fought for Britain in the First and Second World Wars, and especially those who made the ultimate sacrifice, it’s worth noting that memory can be selective, and 80 years after the end of WW2 the sacrifices of millions of people from Britain’s colonies in both wars have been largely forgotten.

It’s a little known fact that 23% of the entire British armed forces in the Great War of 1914-18 were from India. A total of 1.3 million men made up the British Indian Army. Of these, 400,000 (31%) were Muslims and 650,000 (50%) were Hindus. The much smaller populations of Sihks and Gurkhas contributed around 100,000 men each.

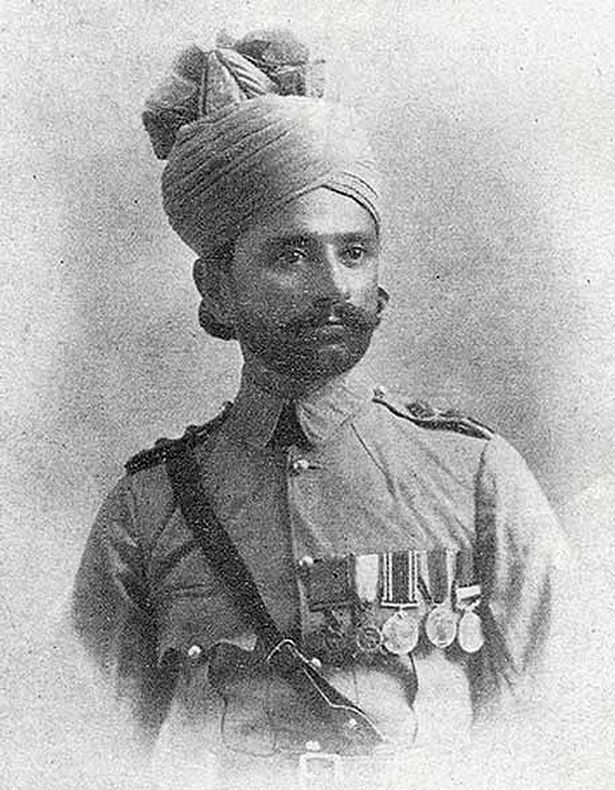

On the 31st October 1914, at the First Battle of Ypres, Pakistani soldier Khudadad Khan became the first non-white recipient of the Victoria Cross, and one of 11 recipients from the British India Army, who suffered 120,000 casualties during WW1.

In WW2 India answered the call to ‘defend the Mother Empire’ in even greater numbers with 2.5 million enlisting, creating the largest volunteer army in history. This included 800,000 Muslims, 1.2 million Hindus, 300,000 Sikhs and 120,000 Gurkhas – 31 of whom were awarded the Victoria Cross.

The Commander in Chief, Field Marshall Claude Auchinleck,famously stated that Britain could not have come through both world wars if they hadn’t had the Indian Army. Yet their contribution seems largely forgotten in portrayals of the wars in movies and popular culture.

India may have provided the most troops but they were by no means the only country in the Empire whose British subjects signed up to fight in both world wars. In 1915 the War Office formed the 15,000 strong British West Indies Regiment, comprising volunteers from the Caribbean islands. They dug trenches, built roads and gun emplacements, acted as stretcher bearers, and maintained the supply of ammunition and, of course, fought on the front line.

In 1917 Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig praised the contribution of the BWIR, commenting on their excellent discipline and high morale. After the capture of Jerusalem in 1917 Major General Sir Edward Chaytor, wrote, ‘Outside my own division there are no troops I would sooner have with me than the BWIs, who have won the highest opinions of all who have been with them during our operations here’.

The most celebrated and decorated BWIR soldier of WW1 was Walter Tull. In 1917 he became the first black officer to lead white soldiers into battle. Tragically he was killed a year later in No Man’s Land, during the Second Battle of the Somme. During WW1 BWIR soldiers were awarded five Distinguished Service Orders, 30 Military Crosses, and 18 Distinguished Conduct Medals.

A similar number of West Indians signed up to fight for Britain in the second world war, with around 3,700 Jamaicans in the RAF alone. One of the most distinguished Black servicemen was Ulric Cross, a Trinidadian who joined the RAF and flew more than 80 bombing missions as a navigator. He was awarded both the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Distinguished Service Order for his bravery.

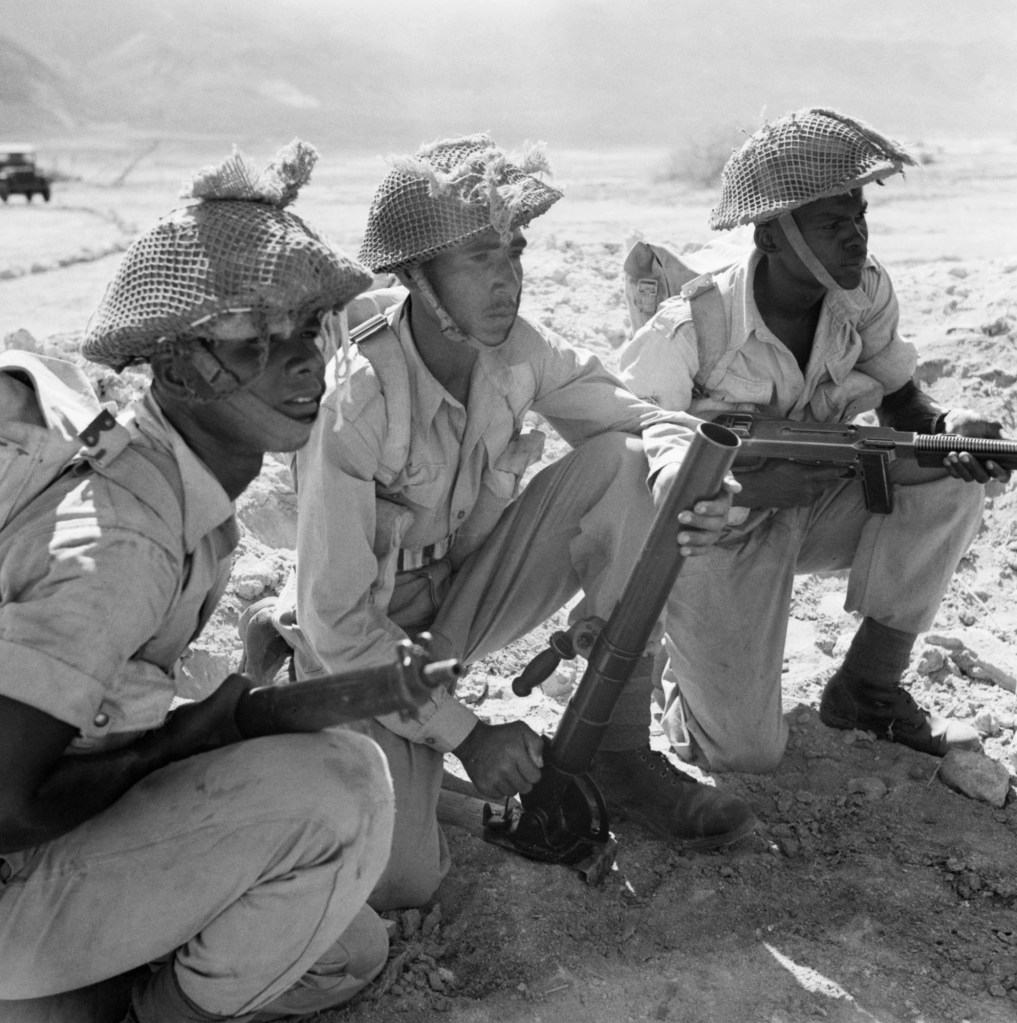

Africa also contributed in huge numbers to the British war effort, with around 680,000 Africans serving in British military units, of whom 161,000 were Nigerian, and nearly 100,000 from Kenya. The most well-known of these were the Kings African Rifles. Originally formed in 1902 they saw action on multiple fronts in WW2, including against Mussolini in Ethiopia and against the Japanese in Burma.

Overall, the contribution made during both world wars by Britain’s colonial subjects across the Empire is immeasurable and yet it is not today as well known as it should be. This fascinating gallery of rarely seen archive photographs from Getty Images shows just how the British war effort was actually a colonial war effort, and should be more widely recognised as such.