Documentary photographer Peter Caton has been on the road for the past 17 years photographing the climate crisis. Peter Dench talks to him about his project documenting floods in South Sudan.

Around 17 years ago, documentary photographer Peter Caton made a life commitment to reporting on humanitarian causes and amplifying the voices of disadvantaged people. For the last ten he has focused on Africa’s climate-related crisis. The decision to live out of a suitcase means he has sacrificed marriage, having children and building a community of friends to bring him up when he’s feeling isolated and low. On a rare visit home to see his parents in his home town of Scarborough on the UK’s North Sea coast, Caton was at an impasse where to go next? ‘I’m not a God-fearing man or anything but I went to church before Covid, I never do but my dad was going.

He hadn’t been for 25 years, my mum goes every week. I decided I’d pop along as well. At church I prayed and said to God, where would you like me to serve you? Where shall I go next because I have this crazy nomadic life. The prayer finished and then it was hymn time and I opened up this book and there was this tiny flag and I was like Woah! What is that about? I didn’t even recognise the flag. I turned it over and it said South Sudan,’ reveals Caton.

For the past three years, homes and schools across South Sudan have been destroyed by devastating floods. Particularly hard hit were the remote towns of Old Fangak and Paguir, cut off as the rising water, debris and dense vegetation left them hard to reach. According to a UN report, 426,000 people have been affected. The number is expected to increase by more than 50%. In areas like Fangak the number of people affected by the floods is expected to jump from 75% to 100%. The country as a whole has surpassed the mark of 8 million people in dire need.

Bol Kek, 45, from Paguir, collects water lily bulbs to be ground up and made into an edible paste. Without fishing nets, it is the only source of food available. Image credit: Peter Caton

Less than a year after his prayer, working with Action Against Hunger USA (AAH) and accompanied by resilient writer Susan Martinez, Caton arrived in the remote Fangak County in Jonglei state in South Sudan. ‘It was far away from anywhere. A small five-seater aeroplane is the only thing that can touch down there on a kind of cow field that’s been previously inundated with water so it’s really uneven. You have to scare any cows away so you do a swoop and come back up and try your best to land. It’s a bit hairy. As soon as I walked into the first classroom where there were, say, 30 families living in absolute squalor with chickens and dogs, at that moment I thought wow, if that was a message from God this is it, this is the reason,’ he says.

If getting there was difficult, photographing in deep flood water was equally challenging. Caton didn’t shy away, in fact he made it harder. ‘For the last decade I’ve been using an H5D-50c digital Hasselblad which brings its own technique. It’s not fast and it’s clunky. You almost need to be intuitive to get the shot sometimes.’ Because of security concerns, Caton was often restricted to photographing in the relative safety of the middle of the day when the light was at its most blistering.

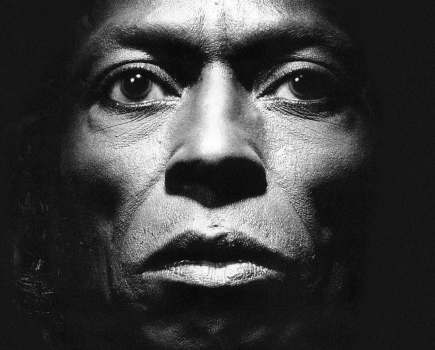

To compensate and deal with the dark complexions of the South Sudanese, Caton uses Elinchrom flash heads. ‘It’s a real logistical challenge. You’ve got a team with you, two guys with you holding flashes on boom arms. One carrying a big battery pack which the Elinchrom needs. In many ways you’re bringing a studio into the field, the Hasselblad lends itself very well to portraiture and that studio feel – you have to work to the strength of your equipment.’

Caton and his team had to be very mindful walking in water; standing still for a few seconds meant sinking into the mud and potentially losing your balance. If the camera got broken, he’d have to switch to his back-up Canon EOS R5 and risk losing continuity of style. To lessen the chance of submerging the Hasselblad, he would walk in the water without any equipment. Once deciding where the shot would be, his tall assistants with knowledge and experience of walking through floods, would bring his camera to him.

Caton could have focused his camera on the squalor and horror of the situation with a more photojournalistic approach but decided on a particular style. ‘I really want these people to be dignified. I had a strong sense from the beginning that people didn’t want to run away, they didn’t want to leave this land. It was their home. It was a bit of a rebel stronghold during the civil war [the South Sudanese Civil War 2013-2020 was a multi-sided civil war between forces of the government and opposition forces] so they’re very much connected, they’ve fought and died for this land. They’re not wanting to leave in a hurry. I was very much wanting to convey that.’

The images have a cinematic quality: 36-year-old Nyalong Wal carries her child to safety in a bucket. 70-year-old Nyakeak uses her stick for balance as night falls. Mother and daughter Nyagout Lok, 46, and Nyakoang Major, 28, set up a bed in the water so the mother can sleep outside as her daughter is pregnant and there is no room to sleep inside.

Mother and daughter Nyagout Lok, 46, and Nyakoang Majok, 28, set up a bed in the water so the mother can sleep outside. Image credit: Peter Caton

In the three years Caton has been photographing in South Sudan, relationships have developed and collaborations formed. It’s this sense of community and teamwork that has helped him get the job done. ‘When I work on the droughts in Somalia then I’ll need security. I don’t need security in South Sudan. A lot of that is down to the relationships AAH has built up with the community over years. In South Sudan I feel quite protected. I’m working with locals who are respected, they’re translating, carrying my lights. As soon as I arrive I have a meeting with the local authority who give us their blessing so you’re protected in that respect. South Sudan is a bit unique like that.’

According to a leading relief agency, at least 11 aid workers were killed in South Sudan in 2022 making it the world’s deadliest place to be one. Caton is undeterred. ‘I know there’ve been incidents with aid workers but by and large, it’s a relatively safe place for foreigners as long as you’re respectful. We were there to help. There are bullet holes in a lot of places from extremely heavy fighting. Everyone carries an AK-47 [assault rifle]. I think it’s almost a rite of passage as soon as they become 18. Some 75% of the people that I walk past who are men had AK-47s. There are a lot of revenge killings that still happen.’

At the end of an intense day’s shoot, Caton withdrew to a small compound the organisation had with a generator to charge his batteries and back up his files. It wasn’t unusual for the generator to fail so in the middle of the night he would have to get a boat across the White Nile River to the Médecins Sans Frontières compound to charge them before returning at dawn. Wherever Caton spent the night he was rarely alone. ‘We were basically staying in a mud hut.

There were lots of snakes and the mosquito situation was absolutely horrific, the worst I’ve ever known working in the tropics for over 23 years. They would be biting your face, your eyelids. As you’re shooting they’re all over your hands. People would slap my face and their hands would be covered in blood from the mosquitos they’re taking off my face. I would charge my gear and jump behind the mosquito net. You’d have your dinner under the mosquito net. You were very much under siege by these aggressive mosquitos.’

The situation got so bad Caton had a tailor make a few suits out of mosquito nets. ‘On the second year there were five of us that came in because the local NGO wanted to bring in some communication people to help us. Within four, five days they were all getting airlifted out due to malaria. There was only Martinez and I left, we thought, who’s next!? We just had to take it one day at a time and if we get sick we get sick, let’s just get as much done as we can. It was quite scary in that way – for some reason or another I’ve never had malaria.’

Nyadiang Gak, 50, from Lakabang Village, stands beside her destroyed maize crops after losing – for two years in a row – her much-needed harvest. Image credit: Peter Caton

Caton’s approach may seem ill-advised but in the context of his profession it makes sense. Ten to 20 years ago he may have been flown in by a client but the preference now is to use someone that’s already there. He carefully chooses regions of the world in which to situate himself that will provide the work he wants to do and it’s working, he receives around 25-30 assignments and commissions a year. ‘I want to be in the field working, that’s my happy place.

To do the jobs I want to do without any compromise, to be there in the field as a humanitarian photographer. That is the only way of doing it so you can work full time; unless you’re affiliated with a top magazine or built a reputation up that you can survive off, that is the only way. I weigh it up, what makes me happiest? Is it having a community around you, having friends, family or is it photographing?

Nyaruot Gatluak, 24, plants rice at the Action Against Hunger rice paddy in Paguir. Image credit: Peter Caton

From 8-19 February 2023, gallery@oxo in the Oxo Tower, London, hosted an exhibition of Caton’s images from South Sudan. Almost 4,500 visitors made the pilgrimage to see Unyielding Floods: Restoring Hope. Using a Hasselblad had borne dividends – the large-scale images of his subjects pinged with critical detail, bringing them face to face with an international audience. ‘I thoroughly enjoyed going to the Oxo Gallery.

It opened my eyes to this idea that I need to be out there a little bit more, physically I need to put it on display, I need to be there networking. It’s difficult to get that balance right. I do believe to a degree that photographs actually help the communities you’re working with; that helps me sleep at night, rather than think I’m taking advantage. It’s consensual – the money my images help to raise can go directly back to those communities,’ he explains.

Growing up, Caton and his two sisters lived in a children’s home run by his parents where they had around 40 other children to look after. Their involvement in social work gave a strong moral underpinning to his early life. His parents are now in their 80s, and his bond with them remains strong. ‘I had nine years living in India where I cut my teeth as a photographer. In those years there were no mobile phones so in those early years my mum was a bit more anxious about me. Nowadays, if she hasn’t heard from me for a few days she just gives me a ring.’ If she can’t get through, she knows God is listening.

Yoak Chatin, 80, rows in his hand-made canoe in Wangkotha Village in Old Fangak. Image credit: Peter Caton

Peter’s website is at www.petercaton.co.uk, and see more about the charity he works with at www.actionagainsthunger.org.

Featured image: An entire family works into the night trying to scoop out flood water that gushed into their land. Image credit: Peter Canton

Further reading:

Documenting the consequences of climate change

Environmental Photographer of the Year 2022 winners announced!

Graeme Chesters – documenting climate change in one of the fastest-warming places on the planet

Portrait of Longyearbyen – Graeme Chesters

Here comes the sun – documenting change in the world’s most northerly town