Graeme Chesters, the winner of AP’s first Rising Star bursary, talks to Tracy Calder about multitasking, storytelling and shooting portraits of Longyearbyen residents in fading light

In partnership with MPB

Returning to life in England after spending the best part of two months in Longyearbyen – the world’s northernmost settlement – must have taken some getting used to. There’s no need to walk to the Co-op with a rifle over your shoulder (for scaring polar bears). The threat of being buried in an avalanche is pretty slim and, crucially, it’s dark at night and light during the day. Longyearbyen is a place that likes to remind you that you are acutely vulnerable, as Graeme Chesters (winner of AP’s first bursary) discovered. ‘On occasion I would walk to the head of the valley and find myself transfixed by the northern lights,’ he explains.

‘I would be fiddling with my camera settings and tripod and staring into the sky when I would hear a noise.’ Glaciers often hiss, creak and sigh – in fact, Stephanie Spray, a PhD candidate in social anthropology once likened the sound to, ‘the belly of the Earth groaning’. But standing alone in the wilderness, Graeme found this sound jarring. ‘You can barely see, then you hear a noise and you feel acutely vulnerable,’ he confides. ‘You know the chances of encountering a polar bear close to town are slight, but in the dark you feel very exposed.’

Portrait of Longyearbyen: Capturing stories

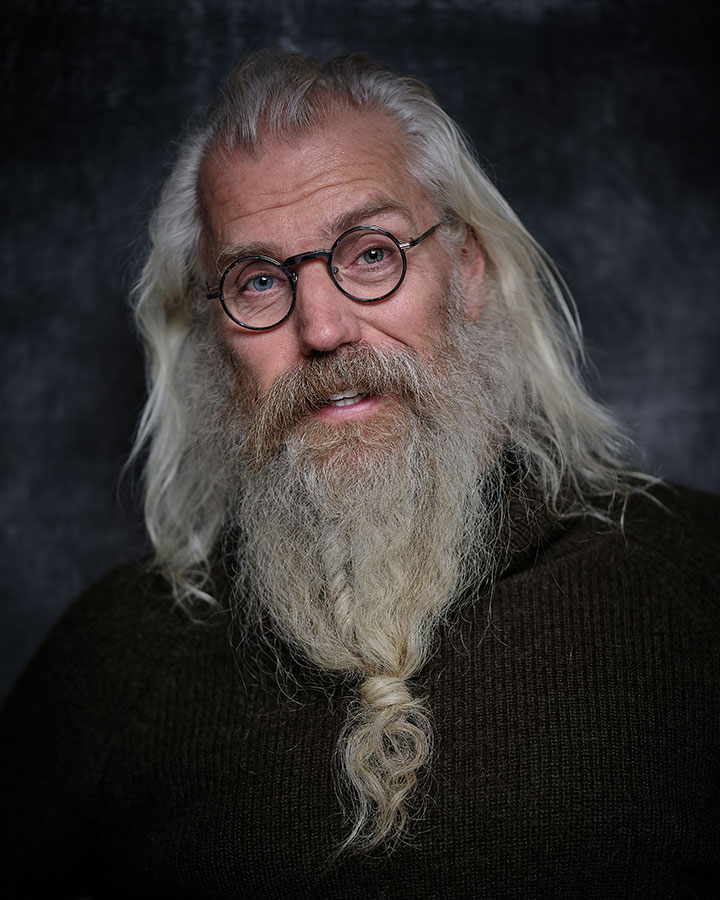

On the flip side, this heightened awareness (and sense of vulnerability) proved to be quite addictive. ‘Being in an environment where there is an apex predator (that isn’t you) and being really attentive to your environment gives you a strong sense of being alive,’ says Graeme. ‘Back home, I have genuinely missed that.’ Perhaps this growing respect for Longyearbyen’s ‘sea bears’ comes from the chats the photographer has enjoyed with the town’s residents over the last few years. Recently, during his stay as artist in residence at the Spitsbergen Artist Centre, Graeme decided to photograph and interview as many locals as he could. An undertaking that resulted in 30 revealing portraits and more than 50 hours of audio recordings. ‘Most people who have been there any length of time will have encountered polar bears,’ he suggests. ‘They all have their stories.’

Graeme’s desire to record still images and audio simultaneously is commendable, but it must have been incredibly challenging to implement. How on earth do you stay present while balancing light levels, engaging in conversation and deciding on the right moment to release the shutter? ‘It was exhausting,’ he laughs. ‘There were points at the start when I thought it just wouldn’t work.’ Having spent extended periods in Longyearbyen on two previous occasions, Graeme had established relationships and, crucially, a level of trust with the townspeople.

‘Even so, people are busy and lots of them have had experiences with people from the outside who just turn up, find interesting characters to photograph and then leave a few days later, so there was some reluctance,’ he adds. Having spoken to Graeme for the best part of an hour, it’s clear that this hit-and-run approach is not really his style. Amiable and open, he is as happy sharing his own stories as he is recording the adventures of others. ‘I found opportunities to share my experiences in a way that didn’t feel inappropriate, and I think this helped with the dynamic,’ he says.

Make do and mend

Sitting opposite Graeme in a room that just weeks before had served as a storeroom for roofing materials must have been an odd experience. While cleaning out the space he came across a piece of sailcloth (thought to have been used by the local photography club back in the 1990s) and decided to attach it to a light stand and use it as a backdrop. ‘It wasn’t necessarily what I would have chosen, but it was very much in-keeping with the “make do and mend” spirit of Svalbard,’ he says.

One by one Graeme’s subjects would arrive, take a seat and start chatting. Nothing was posed or directed – the photographer would simply wait for a gesture or expression that piqued his interest. ‘I would keep the camera (a Fujifilm X-T4) on my lap and lift it to my face occasionally,’ he recalls. ‘As the session went on, people would start to relax and forget about what was happening.’ In time, the mask would fall away, and people would share their stories and, interestingly, their secrets.

Longyearbyen is a wild, inhospitable place, so I’m curious to know if, during the course of these sessions, Graeme learnt any more about what attracts people to this town on the edge of the Arctic circle. ‘I think there’s a sense of possibility among the people who live here,’ he proposes. ‘There’s a kind of unrealised potential that people project onto the place.’ Graeme admits that the idea of ‘finding yourself’ in the wilderness can seem rather hackneyed. But many of the people he spoke to seem to have found personal fulfilment in this isolated place – a fact that he attributes to the strong sense of community.

‘Humans are not meant to be here so when they are they have to look out for each other in a way that binds them very closely,’ he says. But living in a town where everybody knows your business is not without its problems. ‘If your relationship fails, good luck having a date with anybody in public,’ warns Graeme. ‘If you go to the pub on a date everyone in the community knows about it straight away!’ To protect their privacy, people often entertain at home. ‘You start in an intimate way and get to know someone very quickly,’ he laughs.

Balancing the light

Some people found sitting for Graeme so therapeutic they likened it to a session with a psychotherapist. Once word got out that he could be trusted 100% he found himself inundated with requests. ‘In a small community, once so many people have told you their story other people want to be on record telling their story too,’ he explains. Towards the end of the project, he was shooting two or three portraits a day. ‘I found it exhausting,’ he admits. ‘If you do a couple of sessions back-to-back and you’re spending an hour and a half with each person talking, listening, taking photographs and checking what you’ve got (as well as moving the light stand or changing your position) it can be very draining.’

The room that Graeme was shooting in had two large windows, but as the weeks wore on the level of natural daylight began to fall dramatically. On 26th October 2022 the sun set over Longyearbyen and it didn’t rise again until February 2023 (the town won’t actually receive direct sunlight until March). With light levels plummeting, Graeme paired his flash with light from an LED panel. ‘A lot of the portraits are quite dark, but they were taken in the dark season, so it felt quite fitting,’ he explains.

To gather as much light as possible, he kept his lens (a Fujifilm 56mm) wide open, shooting at f/1.2 or f/1.4. Naturally, this resulted in minimal depth of field, but it was a compromise that he was willing to make. ‘People sometimes criticise the autofocus and eye-detection on Fujifilm cameras (compared to, say, Sony). But in poor light the X-T4 performed well for the most part,’ reveals Graeme. ‘After two or three sessions I had enough confidence to know that my planned interview/portrait technique would work.’

In Longyearbyen everyone has a story to tell. During the dark season life becomes simpler and time seems to magically expand. Suddenly there is more time to entertain at home, to admire wisps of green as they snake across the sky, to sit in a wood-lined room and exchange thoughts with a genial photographer. ‘The portraits evoke stories for me, they remind me of moments – humorous, melancholic, reflective and insightful,’ says Graeme. ‘Listening to people is a privilege and I couldn’t think of anywhere better than that small room, high up in an old building, beneath the possibility of the northern lights.’

Graeme’s gear for photographing portraits of Longyearbyen residents

All of the portraits here were captured with a Fujifilm X-T4 and Fujifilm 56mm f/1.2 lens. ‘I love my X-T4 because there are so many dials on the body. Which means that I can set it up in a cold environment without turning it on and draining the battery,’ says Graeme. ‘One of the reasons that I chose the 56mm lens was because it’s weather-sealed and affords me a few extra stops of light.’ In terms of artificial light, Graeme used a Godox V860III (dialled down to 1/125sec) in a modified softbox. A Godox TT350F on the camera as bounce light and to trigger the off-camera Speedlite and a Godox M1 LED panel for times when the natural daylight began to fall. ‘I took two of the Speedlites with me because if one failed, I knew it might take eight weeks to get another one!’ explains Graeme.

See more of the best cameras for portraits here.

Graeme Chesters

Graeme is a photographer and writer based in the North West. After 20 years working as an academic, he is now working freelance on a variety of photographic and journalistic projects. Graeme is also a Fellow of both the Royal Society of Arts and the Royal Geographical Society. See graemechesters.com.

Further reading

Documenting climate change in one of the fastest-warming places on the planet

Here comes the sun – documenting change in the world’s most northerly town

Best portrait photography advice from the pros

How to take better portraits on a budget