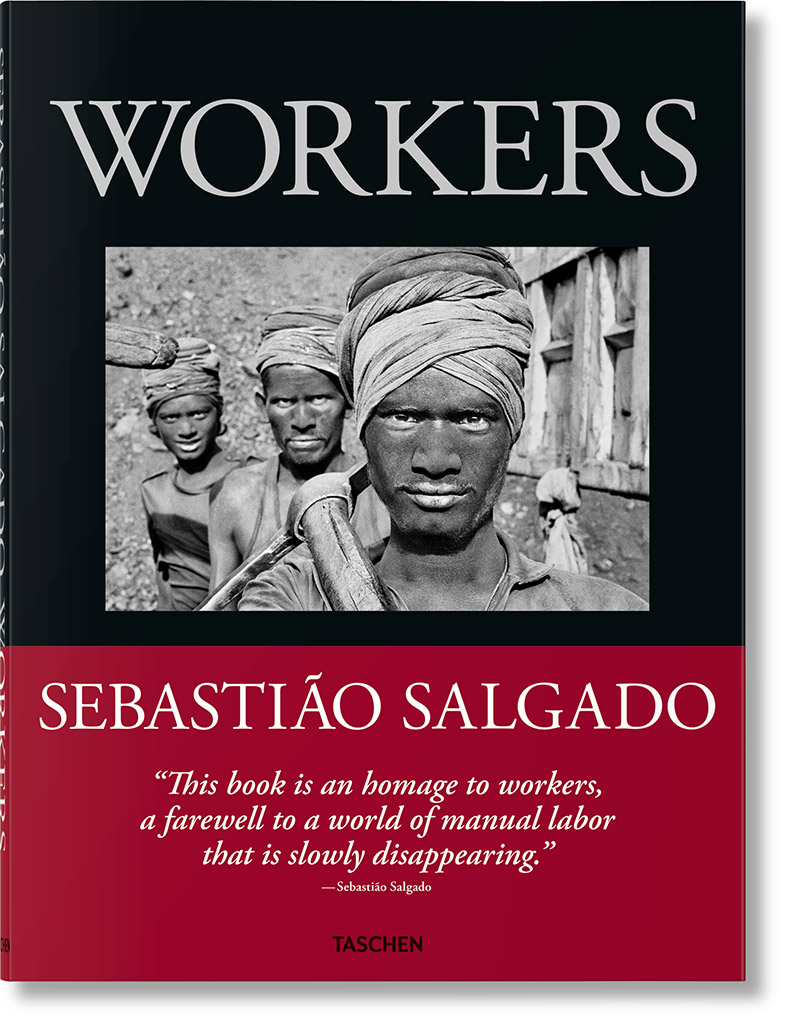

To celebrate 30 years since the publication of Sebastião Salgado’s seminal book, Workers, Peter Dench asks experts in the photography industry what makes the Brazilian photojournalist’s work so special

From 1986-1992, Sebastião Salgado travelled across the globe documenting the end of the first big Industrial Revolution and the demise of manual labour. The result was the classic tome, Workers: An Archaeology of the Industrial Age. The book presented six essential chapters: Agriculture, Food, Mining, Industry, Oil and Construction.

The striking black & white images are an eclectic odyssey, from Russian car factories to the beaches of Bangladesh. Collectively, the book delivered a masterclass in photographic technique – content and contrast, lighting and composition. It is testament to the best attributes of the power of photography and what can be achieved through collaboration between subject, sponsor, publisher, editor, colleagues, friends and family.

Thirty years on from its first publication in 1993 and now republished by Taschen, Workers still resonates, perhaps more so as the world’s population is increasingly sucked into a screen/computer/robot-led existence. To mark the anniversary and the book’s republication, we ask leading figures in photography about the significance of Workers, Salgado’s importance and his influence on their craft, and their favourite of his images from this important book.

Andy Greenacre – Director of Photography, The Telegraph Magazine / Telegraph Luxury

‘There are a great many photographs by Sebastião Salgado that have attained iconic status within the canon of his works, but from Workers I have chosen what might, at first glance, seem a more prosaic image. Shot in 1990 at the Brest military shipyard in France, the picture of a welder, shown below, works on several levels.

‘First, the composition and scale is much tighter than many of Salgado’s photographs, yet it retains a sense of crackle and drama with him shooting so close to the sparks being thrown off the steel. Second, we are treated to his trademark printing with absolute whites and inky blacks. But what I like

most about this picture is the nod to the surrealism in the work of photographers of the 1930s, in particular Cartier-Bresson and Alvarez Bravo.

Salgado’s low shooting position gives us that eye within an eye, a touch of humour that adds another dimension to the photograph. From record of

industry to surrealist fun, this is a great example of Salgado’s ability to imbue his works with multiple levels of depth and interpretation.’

Carol Allen-Storey – Award-winning photojournalist chronicling complex humanitarian and social issues

‘Sebastião Salgado’s style of photography, for me, fosters poetic beauty embracing brutally raw subjects – from poverty through to the oppression of cultures and the impact of industrialisation on the natural landscape. His photographs go beyond language and culture, reaching deep into our souls and challenging us to reflect on the world we live in. They provoke debate and a call to action.

‘Salgado said: “I’m not an artist. An artist makes an object. Me, it’s not an object, I work in history, I’m a storyteller,” and “Photography is a language that is all the more powerful because it can be read anywhere in the world without the need for translation.” His exquisitely crafted visuals and personal philosophy have had a profound influence on my brand of photography.’

Nigel Atherton – Editor, Amateur Photographer

‘There are key moments in all our lives that shape who we are and what we believe in, and one of mine was the day in 1993 that I went to the Royal Festival Hall in London to see Sebastião Salgado’s Workers exhibition. Oil workers, gold miners, ship-breakers, fishermen, farmers, tea pickers and others were all sympathetically but beautifully photographed like the heroes of an epic visual poem.

‘It was my “red pill” moment, showing me for the first time how the comforts that we enjoy are so often built upon the exploitation of some of the world’s poorest people. Salgado’s next project, Migrations, which focused on migrants, refugees and displaced people around the world, many fleeing conflict or natural disasters, was equally powerful and is just as relevant today. His subsequent projects, Genesis and Amazonia, focused on humanity’s relationship with nature and were no less epic in scale and visual impact.

‘Choosing just one Salgado image is tough, but I feel I have to go with one of the images that first made my jaw drop all those years ago, from his now-iconic 1986 project on the Serra Pelada gold mine in Brazil. The astonishing sight of 50,000 men digging for gold in the mud of the Amazon, like a scene from Dante’s Inferno, or the building of the pyramids, is one that has stayed with me. This mine is now closed, but it’s a blight on humanity that millions still live similarly wretched lives.’

Russ O’Connell – Picture Editor, The Sunday Times Magazine

‘Salgado is one of those rare and prolific photojournalists who documents world events and natural world scenes with an honest yet artistic eye. His monochromatic images often play with scale and perspective in a way that is both intriguing and awe-inspiring. From his iconic images of workers in the burning oil fields of Kuwait, to the majestic tail of a southern right whale in his Genesis works, he never ceases to amaze me with the scope and detail of the work he produces.

‘My favourite image of his (Serra Pelada gold mine, Brazil, 1986) is biblical in scale, akin to a scene from an Indiana Jones feature film. It shows a worker in a Brazilian gold mine, standing like Jesus on the cross, while hundreds of other workers scurry up and down primitive ladders like ants carrying earth on their backs. It’s hard to believe it is a real scene and not an orchestrated film set, but that’s the beauty in Salgado’s work; it always leaves you stunned by its undeniable reality.’

Edmond Terakopian – Photojournalist and commercial photographer, winner of the British Press Awards Photographer of the Year award

‘I think most of us can remember the photographs that grabbed us and completely shook us to the core, staying with us for life. Salgado’s ‘Crucifixion’ photograph from the open gold mine at Serra Pelada in Brazil from 1986, is just such an image. It engaged me both emotionally and intellectually.

‘The scale of it is immense. It’s a photograph that captures a grand vista showing almost ant-like colonies of men in the background, creating a dramatic mosaic of suffering for a meagre wage, yet at the same time juxtaposes an amazing portrait of absolute exhaustion, elegantly, with immense gentleness and empathy. A man broken through a day of hell, all to feed the super-wealthy with their obsession for wanting more and more gold.

‘On a personal level, at the age of 17, a year after starting photography, this image also changed the direction of my life. It opened my eyes to what a camera could produce, when in the hands of a thoughtful, intelligent, empathetic photographer, with immense aesthetic talent. It set me on the path to wanting to be a photojournalist. I could even say that I owe my career to this photograph.’

David Collyer FRPS – RPS Documentary Photographer of the Year 2021

‘Every artistic genre has its standout practitioners; those who transcend the ordinary or even the extraordinary to become indisputable masters. Sebastião Salgado is one of photography’s masters. Not only are his campaigning photojournalism and social documentary work vital in showing the plight of some of the world’s most vulnerable and exploited people, but he does so with a consistent technical excellence. Importantly, his work is also visually stunning. Each photograph, a sumptuous feast for the eyes, is an unflinching gaze into the realities of the subject, yet is never done with anything other than respect and empathy for those he portrays.

‘Choosing a favourite Salgado image is almost impossible, but I’ve chosen the photo of the ship Prodromos being broken up in Bangladesh in 1989. The workers are imperative to the shot but dwarfed almost into non-existence by the looming hulk of the ship; they are vital yet somehow insignificant. The juxtaposition of the might of the vessel and the diminutive, exploited scrap workers is a perfect metaphor for the whole of Salgado’s work.

It really is a powerful testament to the battle between man and the elements, and the planet and the excesses of man. This shot has everything, yet unlike so much of his work, it’s strangely minimal in its composition. The strength of the shot, however, is that because of that sparse presentation, its impact is masterfully maximal. Genius!’

Tom Oldham – Photographer, Founder of Creative Corners, AP’s Hero of Photography 2023 and Sony Imaging Ambassador

‘Describing Salgado’s impact on photography is nigh-on impossible as he transcends the form. Us mere pixel- peepers aren’t asking what lens or format or megapixels or developer he’s using, are we? In no way is this work about the technical (though of course he is a master) – it’s so much more about how can anyone capture such magnitude, such incredible enormity whilst retaining that essential relatability necessary for an image to be about humans.

‘For me, what Salgado is to photography, The Beatles are to music and Ali is to boxing – you easily forget the medium and focus just on the message. The depth of understanding and pure power in those compositions has created change in us all, and for that the world owes Salgado a colossal debt.’

Ian Berry – Leading British photojournalist and Magnum Photos member since 1962

‘The first thing about Sebastião is that he’s a great photographer. Secondly, he has a background as an economist working for the World Bank which gave him a wide knowledge of global affairs and conditions. Lastly he’s a terrific guy, which is a great combination for a photojournalist/documentary photographer.

‘It was on his travels to Africa for the World Bank that he first started seriously taking photographs of the people he met. Then in 1973, he abandoned his career as an economist to concentrate on photography, working initially on news assignments before veering towards the work for which he is well-known. In 1979 he joined Magnum Photos, resigning in 1994 to start his own agency, Amazonas Images, in Paris with his wife Lélia.

‘I have sad memories of Magnum board meetings when there were discussions between two distinct sides on the board about where Magnum was going. Sebastião said that if Magnum didn’t maintain its editorial outlook he would quit. Things got heated. Sebastião rose, apparently about to depart, when Henri Cartier-Bresson got up and wedged a chair under the doorknob – a symbolic gesture to prevent him leaving. Then things became more peaceable but flared up again at a later board meeting when he rose to explain why he would leave Magnum and was basically ignored. He quit and I drove him to Heathrow to fly back home.

‘Although he decided to leave Magnum he has gone on to greater things, producing wonderful books with his capacity to spend years on a project. He is what Magnum should be about and is a great example for any budding photojournalist / documentary photographer.

‘Another side to mention is that he is also a passionate believer in preserving the environment. In 1998 his wife Lélia and he created Instituto Terra, an environmental organisation that aims to promote the restoration of the Rio Doce valley. Instituto Terra, besides advocating reforestation, promotes environmental education, scientific research, and sustainable development. For his part he has planted thousands of trees on his organic farm in Brazil.’

Tiffany Tangen – Head of Content, Wex Photo Video

‘Rembrandt became synonymous with the Golden Age because he was able to paint preternatural light, and for the same reason Sebastião Salgado is synonymous with photography. Spending a lifetime documenting the world in uncontrollable conditions, Salgado is able to see the light, regardless of what’s unfolding in front of him; to capture truth and trauma so beautifully is a rarity, and one that allows the audience to connect with a situation more wholly.

‘My favourite image from the Workers collection is ‘Coal Mining, Dhanbad, Bihar, India, 1989’ (above). Salgado encapsulates a sense of individuality against a backdrop of sameness, like ants marching towards summer. His ability to connect you with the subject allows you to see both the solitary man, and the army marching behind. The two perspectives offer an all-encompassing visual story. The ability to document so beautifully, and in such an image-saturated world, gives scope for the general public to care more, which is something that is entirely welcomed.’

Book Review – Workers: An Archaeology of the Industrial Age

Workers is widely recognised as an exploration of the activities that have defined labour from the Stone Age through the Industrial Age to the present. Faithful to the spirit and intent of the original publication, it pays tribute to the time-honoured tradition of manual labour.

‘This book is an homage to workers, a farewell to a world of manual labour that is slowly disappearing and a tribute to those men and women who still work as they have for centuries,’ writes Salgado. His lens elevates the workers to hero or saint. The constant companions of manual labour – poverty, disease, exploitation, injury – are largely ignored. It unapologetically avoids straying from the frontline of the working environment into people’s private lives.

That’s the Salgado way of taking pictures, to eulogise his subjects and present the best comprehension of human beings and the human condition. To show how the spirit of man prevails in the harshest of conditions. To deliver a message of endurance and hope. Every social documentary photographer and photojournalist has their own eye and a decision to make about what to record and take responsibility for what to leave out, in order to construct a narrative that can effect positive change. Salgado’s method provides a valid historical truth within a framework about workers, how the world works and what unites race and nationalities.

‘Salgado unveils the pain, the beauty, and the brutality of the world of work on which everything rests,’ wrote playwright Arthur Miller on the book’s original publication – a description that would be equally valid if written today.

Workers: An Archaeology of the Industrial Age by Sebastião Salgado is published by Taschen, RRP £80. www.taschen.com

More reading:

Follow AP on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube and TikTok.