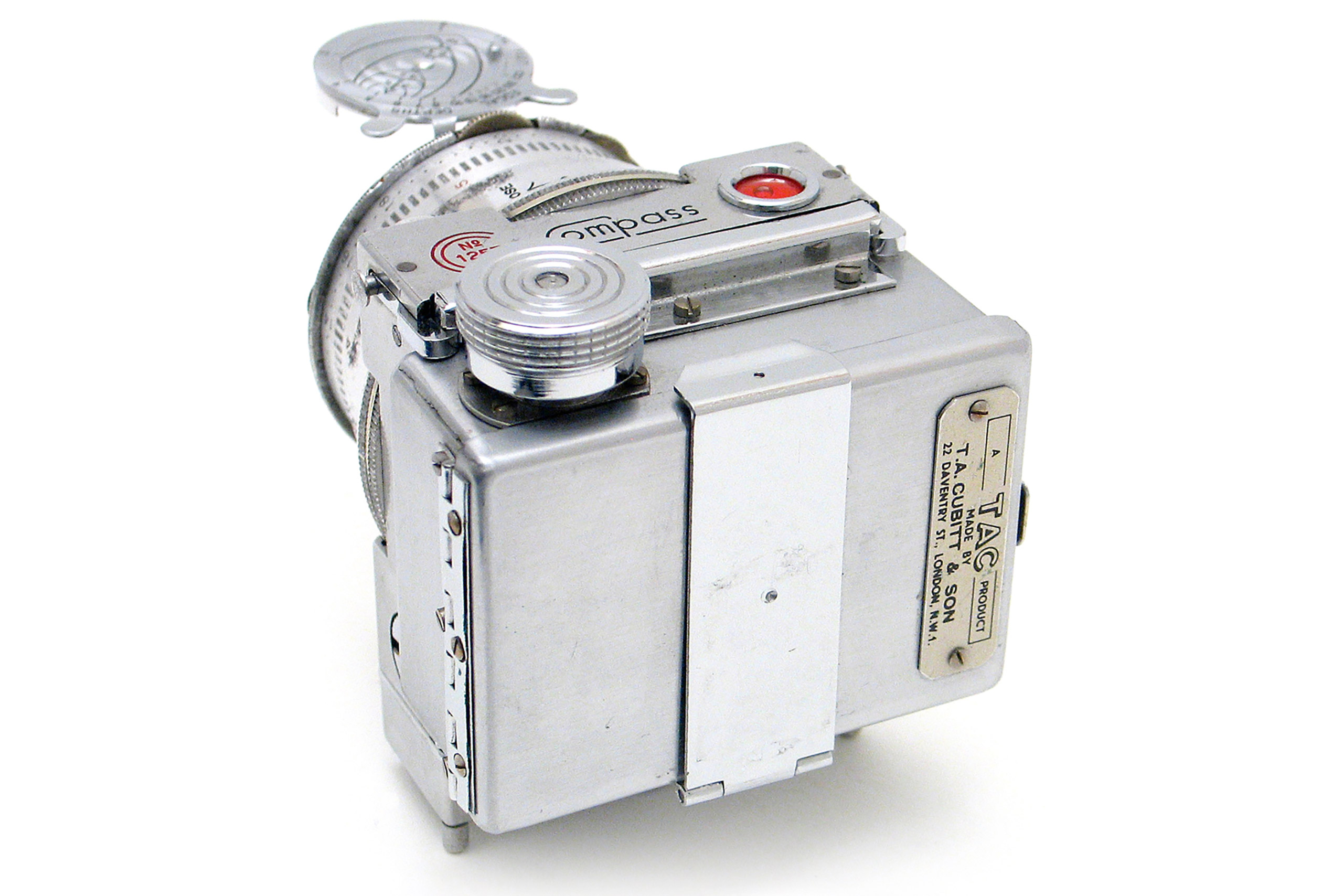

When it was launched in 1937, the Compass was probably the most complicated miniature camera ever made. Measuring a mere 6.5×2.5×5.5cm, it packed into its trim body a multitude of features to cover just about every aspect of photography.

This remarkable film camera was designed by English entrepreneur Noel Pemberton Billing but, unable to find a company in Britain to take on the high-precision work necessary for its manufacture, he turned to Swiss watch maker Le Coultre et Cie. During the early production process, faults were discovered which resulted in the first model being recalled and replaced with the second model. That’s the one most often seen today.

The Compass camera: basic spec

Machined from plated aluminium alloy, the highly polished body features a lens that extends on two telescopic tubes. To their rear, inset into the body, a knurled collar rotates to rack the lens in and out for focusing, aided by a rangefinder beside the viewfinder. A spirit level built into the top of the body helps keep the camera level. The viewfinder can be adjusted for shooting candidly at right angles to the subject.

The lens is a 35mm f/3.5 Anastigmat. Shutter speeds, set on a ring around the lens, use clockwork to give 1/500sec down to a full 4.5secs. There’s a built-in lens hood and a hinged lens cap that contains a depth of field scale. Below the lens two shutter release buttons offer instantaneous or time exposures.

Two small thumbwheels are set one each side of the lens. The one on the left dials apertures into place on a rotating disc between lens elements. The other dials in a yellow, orange or green filter, or leaves the lens clear without any filtration. Beneath each of these thumbwheels a tiny circular window reveals different numbers and letters as apertures and filters are dialled into place.

The Compass camera: setting the exposure

Measuring and setting the exposure on a Compass is an art in itself. First, an extinction meter, or ‘speed meter’ according to the engraving beside it, is employed to measure the light. A metal strip is pulled out from the side of the body which has the effect of progressively darkening the viewfinder by means of a thin glass panel graduated from clear to opaque. When the view through the viewfinder just disappears, a number is read off the metal strip. That number is set on a secondary scale alongside traditional shutter speeds, which gives the correct shutter speed for a full-open aperture of f/3.5.

To use a smaller aperture, the photographer dials it in on the appropriate thumbwheel, keeping an eye on the window to the left of the lens, where letters and numbers appear according to the aperture set. The first number ascertained from the extinction meter is then added to the number from the aperture window and the result set on the shutter speed ring, giving the correct speed for the aperture in use.

Dialling in any of the three filters on the other thumbwheel, gives yet another number in yet another window. This number is then added to the aperture and extinction meter numbers, and the result is set on the shutter speed ring, giving the correct shutter speed for both the aperture and filter in use.

For those who find all this too complicated, there is also a ‘Snap’ setting on the shutter speed ring, designed for use with the letters displayed alongside the numbers in that aperture window beside the lens, their meanings indicated on an engraved table below: ‘D’ for dull, ‘O’ for overcast, ‘C’ for clear, ‘B’ for bright.

The Compass camera: stereo and panoramic pictures as well

On the base of the body a short lever folds out to turn through 180° in five click-stopped positions. Screwed into compartments on each side of the body are two more devices for use in conjunction with this lever.

One is the panoramic head, the other is the stereo head. Each is screwed into the pivoting arm beneath the body and then attached to a tripod. The panoramic head allows the camera to be turned through the five click-stopped positions to shoot a series of pictures for joining after development to make a panorama. The stereo head allows the camera, to be laterally shifted between two exposures to give a stereo pair.

The Compass camera: cut film

The back of the Compass incorporates a ground glass screen and magnifier to aid picture composition and focusing. It’s the kind of thing you are more likely to see on a much larger plate or cut film camera. Unsurprisingly, then, the Compass uses cut film. Each sheet is individually stored in a small, light-proof paper envelope with its own dark slide. This is dropped into the back of the camera. The image size is 24x36mm, the same as that from a traditional 35mm camera.

With the focusing screen removed, the camera can be equipped with its own roll film back, also produced by Le Coultre for special-size Compass roll film. An independently made back is also made for use with Kodak’s 828 Bantam size film. Today this is even rarer than the camera.

The Compass camera: the tripod

The only other accessory made by Le Coultre for the Compass is a very special tripod. At first sight it looks like a silver tube, 14cm long and the shape of a fountain pen. But unscrewing a cap allows three legs to be extracted, reversed and attached back onto the tube. From the legs, three extensions fold down to make a tripod 30cm high, complete with a miniature ball and socket head on top.

But at the end of the day, the Compass didn’t really need many accessories, because it had so many already built in. And it was that which probably led to its downfall. Despite advertising that proclaimed ‘built like a watch – as simple to use’, so many features and controls crammed into such a small body proved too fiddly for many photographers. Within a few years of its launch, the Compass quietly died away. In all, less than 3,700 cameras are thought to have been made.

The Compass: Prices then and now

- Camera Original price £30, price now $3,300-5,300 / £2,500-4,000

- Roll film back Original price £5, price now $400-650 / £300-500

- Tripod Original price £2, price now $800-1,200 / £600-900

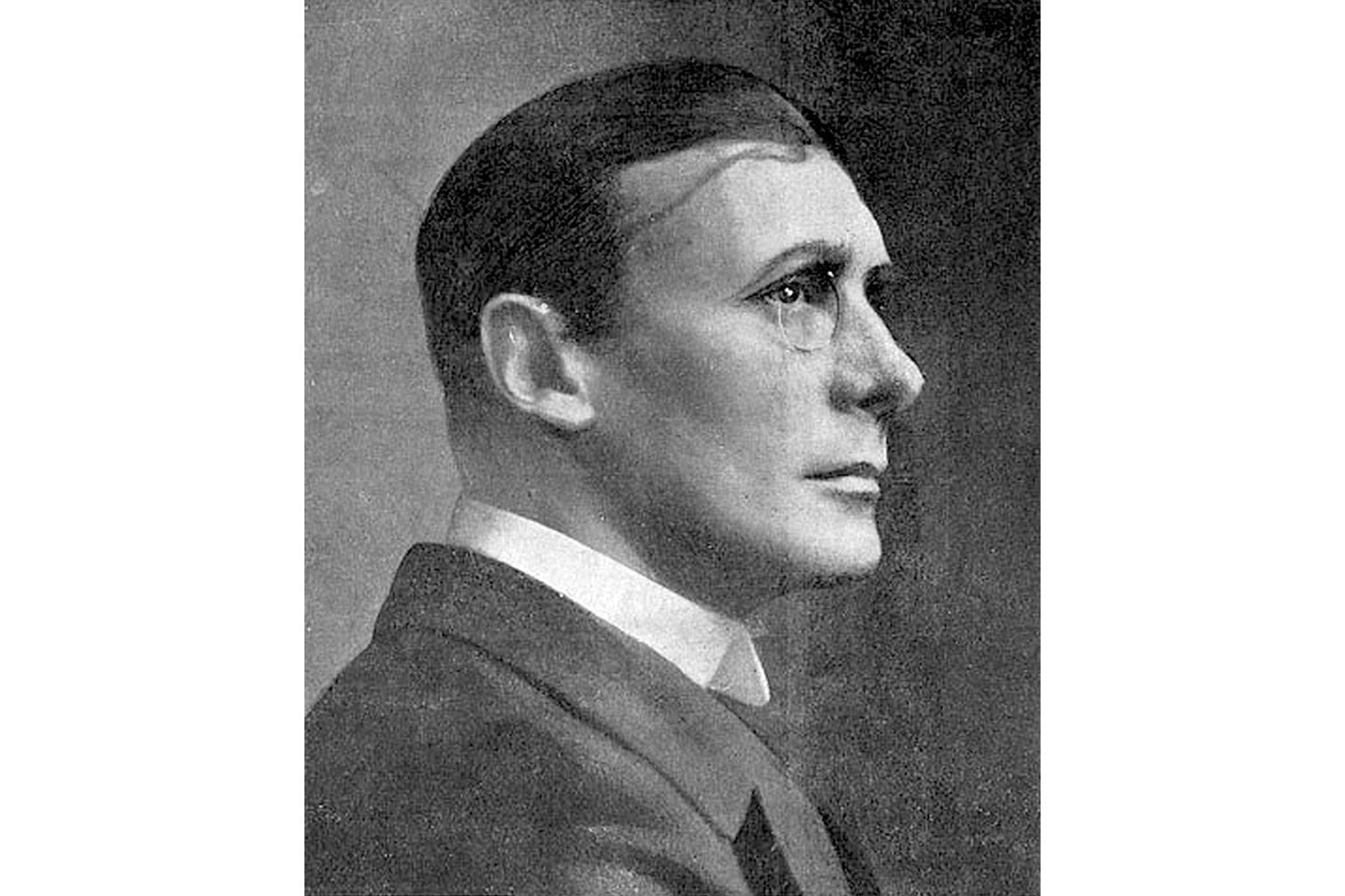

The genius behind the Compass

Noel Pemberton Billing was born in London and educated in Britain and France. He began his career in South Africa, where he designed military equipment. He gambled in Monte Carlo and built a casino in Mexico before returning to England to become a publisher, actor, theatre manager, cinema manager, playwright, science-fiction author and property developer. He launched a shipping business, trained as a barrister and was elected as a Member of Parliament for East Hertfordshire.

Up for a challenge

He designed furniture, a typewriter, a flying boat and a single-seater fighting aircraft. He was responsible for a machine to make and pack self-lighting cigarettes, a movie projector that could be synchronised with a wind-up gramophone, a golf-practising device, a cloth-measuring tool and even a type of helicopter called a Durotofin.

The size and design of the Compass were the result of a bet, when he was challenged to come up with a fully specified workable camera that would fit inside a cigarette packet. He designed the Compass in two weeks.

See the Compass camera in action in our exclusive video:

Related reading:

- How to check if a film camera works

- How to make a pinhole camera

- Get the film look with digital editing