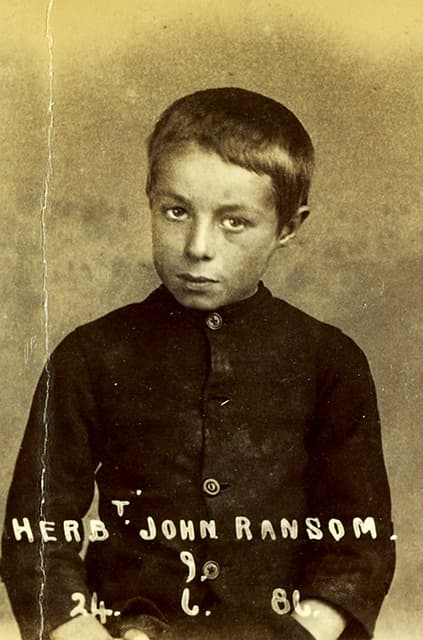

Herbert John Ransom [Credit: Barnardo’s]

The newly released records date from 1887, when Thomas Barnardo sent 320 boys, many from slums in London’s East End, to live with people in villages across the south and east of England. There, they could experience fresh air and the countryside.

‘Foster carers were sought who didn’t live close to factories or railway stations, and had space to make sure children never slept more than two to a bed, to help children escape from polluted, overcrowded urban slums,’ says Barnardo’s.

Lilian Murray [Credit: Barnardo’s]

The charity added: ‘Children placed in Barnardo’s foster care in the Victorian era had often previously experienced abuse or neglect.

‘Archive medical records show a third of the first 457 boys who entered Barnardo’s care had rickets, 21 had ringworm and they often had bad teeth.

‘Once children moved into foster care they showed marked improvement in health and development at school.’

By 1889, a quarter of children fostered through the scheme were girls, many who had been at risk of sexual exploitation.

Elizabeth Mouncey [Credit: Barnardo’s]

By the time of Thomas Barnardo’s death in 1905, 4,000 children had been looked after in foster care.

Barnardo’s chief executive Javed Khan said: ‘Much has changed over the past 130 years, but there are still vulnerable children who simply need someone who can always be there for them.

‘Just as in Victorian times, today we’re looking for people, with a genuine desire to make life better for some of the country’s most vulnerable children, to become foster carers.’

Barnardo’s has also released records of the Victorian foster children in its care:

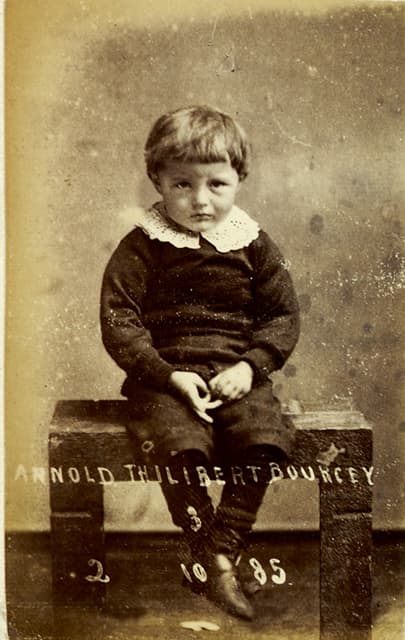

Arnold Thilibert Borsay

Born: 2 August 1882

Arnold Thilibert Borsay [Credit: Barnardo’s]

Arnold made regular donations all his life to Barnardo’s in thanks for the 13 years of care he received, including seven years boarded out in the pretty hamlet of Eyke, on the Suffolk Coast.

He left Barnardo’s in 1898 to work at the Hotel Belgravia on the prestigious Victoria Street, London, before migrating to British Columbia, Canada, in 1902 under the assisted passage scheme.

Arnold was born in a beautiful mountainous region of Switzerland to Julie, a kitchen maid. His father disowned him and deserted his mother. This may be why as an adult Arnold chose not to be known by his father’s name; Thilibert.

Arnold lived in Vaud, Switzerland, not far from his mother where she could visit him. It’s unclear how Arnold came to be in London, but his mother signed the full agreement, handing him over to Barnardo’s in October 1885 when he was just three years old.

His entry record describes him as a ‘most engaging little fellow… who prattles very prettily in a peculiar Swiss patois’.

In 1886 at the age of four Arnold was boarded out with Reverend and Mrs Darling. He remained with them until 1893 and then moved in with the vicar’s gardener and wife Mr and Mrs Whyard and stayed with them for five years…

Reverend Darling, vicar of Eyke, came from a humble background in Northumberland. A wealthy patron enabled Darling to study at Trinity College, Dublin. As a result, he wanted to help other children from humble origins. According to Eyke village school records, where they taught, Reverend Darling and his wife took in around 100 Barnardo’s children as well as ‘local paupers’.

Arnold died on 18 September 1963, generously leaving Barnardo’s $21,000 in his will, which would be worth around £134,000 in real terms today.

Elizabeth Matthews (alias Hiles)

DOB: 30 October 1876

Elizabeth Matthews would have been sent to the workhouse, were it not for Barnardo’s.

Just a week before her 13th birthday, she was taken in by a Mrs Smith at a Barnardo’s ‘receiving house’ in Copeley Hill, Birmingham.

A few days later, on 2 November 1889, her step-father signed an agreement for Elizabeth to be looked after by Barnardo’s, where she remained for the next eight years.

The preceding two years must have had been tough for young Elizabeth.

In June 1888, Elizabeth had run away from her step-father. She went to her step-grandparents, hoping to seek refuge with them. Sadly, they were both too poor and too advanced in age to support her.

Her mother had died in December 1887, leaving her with two step-siblings and her step father, George Lueds. Nothing was recorded about her father.

Elizabeth’s entry record, number 2,000, describes her predicament:

‘This poor girl ran away from a tramping step-father, who is a cripple, and earns his living by hawking, begging, and singing… [He is] now roaming the country with one of his two children, a boy – and lodging in the lowest lodging houses.’

Elizabeth spent the first two and half years in a Barnardo’s home, before being placed with a foster family in the rural hamlet of Abbots Roothing in Essex, where she lived for four years.

Elizabeth’s final move was to Barnardo’s Girls Village home in Barkingside where she remained for two years to undertake domestic training.

In November 1898 – nine years and two weeks after her step father signed the admission agreement –Elizabeth left Barnardo’s to enter service.