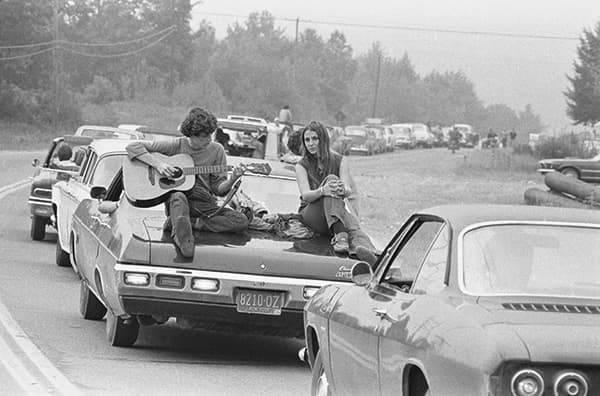

A couple play the guitar sitting on their car on the way to the Woodstock Festival, August 1969

The mid-20th century was a time of fierce transition in US history. The spectre of the Second World War was receding into the annals of memory (at least in that part of the world), and advances in medical research meant that parents and children could finally escape the shadow of polio. The dark tornado of McCarthyism was still fresh in the mind, but was being superseded by the horrific shadow of the Vietnam War, and that’s to say nothing of the public slaying of a beloved president. Within all of this, the boundary-shattering progress of the civil rights movement marched on, refusing to falter in the face of a fractured social landscape.

It seems inevitable, then, that something in the social psychology of the American people would have to give. But rather than take up arms, a generation of young Americans instead decided to abandon all hope of an ordered and structured society, and pursue a philosophy that was founded on love and peace. What replaced the ideals of the conservative and suburban nuclear family was the hippy movement – a youth subculture of men and women who were more interested in consciousness expansion, experimentation, nature and communal living, rather than the polished kitchen surfaces and Teflon of their forebears. Guns, God and government no longer occupied the idol’s throne – the Grateful Dead and Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters were in town.

At the heart of this – actually at the tail end, in 1969 – was the now legendary Woodstock music festival in New York state – an event that to this day still carries sparks of nostalgia, even for people who were born some years later. The festival was conceived as a three-day event of peace and music, and was expected to attract 50,000. What occurred, as we now know, exceeded expectations – the festival attracted half a million people and has gone down as one of the most legendary music events in history. What sat at the heart of the festival was revolution – the belief that as a community, those wishing for a better life could come together to demonstrate their unified hope; by acting as one, people really could make a difference, particularly when they were immersed in the transformative power of love, music and mind-altering psychotropics.

The festival (officially called the Woodstock Music & Art Fair) was meant to last for three days – 15-17 August 1969 – but ended up overrunning by one more day. One photographer who was present during those groundbreaking few days was Rolling Stone staff photographer Baron Wolman. His images are notable for one key reason – rather than attempting to get winning shots of the musicians, such as Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix, performing on stage (although there are a handful of these), the majority instead focus on the audience. As Wolman says, he often found himself out in the wild with the crowd, as what he found there – the people, the community – was too significant to ignore. It’s this approach that makes the collection of images so significant.

Rather than being a straight document of the festival, Wolman’s images are a political and social record. There’s something almost anthropological in the approach. Each frame is a raw and honest approach to a people who were, for a time, experiencing the dawning of a new age. The fact that the new age was illusory makes this seem all the more bittersweet.

Just four months later, police investigating the murder of actress Sharon Tate apprehended cult leader Charles Manson and members of his ‘family’. The fact that Manson and his family came from within the hippy movement only served to emphasise the delicate nature of a subculture attempting to function in the dark outlaw heart of America. The 1960s had officially ended.

Woodstock by Baron Wolman runs until 11 September at Proud Camden, The Horse Hospital, Chalk Farm Road, London NW1 8AH. Entry is free. For more information, visit www.proud.co.uk