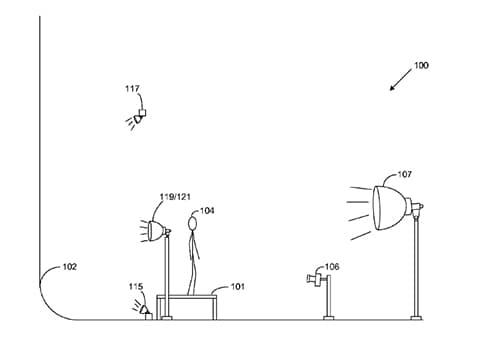

The patent, granted on 18 March 2014, relates to ‘various embodiments of a studio arrangement’ and a ‘method of capturing images and/or video’.

The patent claims each concern a ‘background comprising a white cyclorama’, image capture position and the placement of light sources.

One details the use of an 85mm lens and an image captured using an aperture of around f/5.6.

Should photographers be fearful?

How worrying is the patent – the document for which spans nine pages – for UK photographers?

As it has been filed in the US, this means it is principally directed to those in the US, says patent attorney Peter Thorniley of London-based firm, Kilburn & Strode.

‘If you have a product [patent] claim then it covers people making, using, importing, selling that product – but in the country that the patent is applicable for,’ he tells AP.

He cautions of a ‘chink in the armour’, however, that could potentially affect somebody acting outside the US – and selling photos in that country – because the patent contains a claim referring to ‘method’.

‘In the US and Europe it is possible to infringe a patent by selling or making a product off a process,’ he explains.

Thorniley suggests that the ‘output’, in this case, is a photograph.

He stresses, however, that this would only represent a ‘small window’ for anyone filing a claim for patent breach.

‘It’s not very often tested. In the past, US patent law decisions have suggested it would only count for a product that is a physical tangible object.’

This course of action is even more unlikely given that it has to be the direct product of that process, asserts Thorniley, who has been a patent attorney for 10 years.

‘So, if you’ve modified the output in some way, it’s possible that doesn’t get caught.’

‘Not a great threat’

‘The truth is, in practice, I don’t think it’s a great threat, but it’s not possible to immediately exclude the possibility that you could get caught under those provisions.’

In any case, Amazon may find it tricky to catch infringers among the many who choose to photograph products on a pure white background.

Would be possible for somebody to realise, just by looking at an image, that a particular studio set-up had been used to take the photograph?

‘It seems extremely unlikely, in practice, that they could have any inkling, or any way of discerning if you are a photographer in the UK who, say, occasionally sells photographs in the US. It’s very unlikely they’d have any cause to think you were using their product…

‘How can you distinguish an image created through their [Amazon’s] process, from an image created in another way, to which some post-production has been applied? I am not sure it would be immediately obvious.’

Corporate infringers in firing line?

Thorniley questions why Amazon felt it worthwhile filing a patent in the first place.

‘In practical, commercial, terms it’s not going to be worth their while engaging with every photographer who sells an image of a product on a white background because, first of all, the vast majority won’t be infringing the patent anyway.’

A photographer who breaches the patent would have had to carry out all the features in one of the claims.

‘In this document there are 27 claims… of those only three are independent – the rest build onto existing ones. But the first two are independent and define studio arrangements which have a large list of things you would have to do to infringe.

‘So you wouldn’t infringe if you didn’t carry out any one of those quite specific requirements.’

So, what’s the point of the patent then?

Thorniley speculates that if Amazon were minded to target an ‘industrial operation’ – particularly in the US – it could seek a court order to find out what such an outfit was up to.