To mark Amateur Photographer’s 130th anniversary issue, Roger Hicks, in his cameras timeine, looks at some of the key cameras that have pushed the boundaries of technology at the time.

Lancaster tailboard camera – 1886

On a ‘tailboard’ the front of the camera is rigidly fixed to the two-piece hinged base-plate, which folds up behind the ground-glass and protects it for transport. For use, the tailboard is dropped and the back is pulled out for focusing. The design goes back to the 1850s but was still the norm for professional and serious amateur cameras when AP was launched: the sort of camera that many AP readers would have been using. This particular model was introduced in 1886, but numerous similar cameras were still available even into the 20th century. Shutters became more popular after about 1890.

Kodak – 1888

The original Kodak was commercially one of the most important cameras ever made. Its appearance and function was akin to basic ‘detective’ cameras of the 1880s and 1890s. The 100-exposure film, which had to be returned in the camera to the manufacturer for processing, was unlikely to appeal to the amateur who wanted to take maybe a dozen pictures in a day and process them himself. It was a toy for the newly affluent: who today might buy a big-screen TV and the latest iPad.

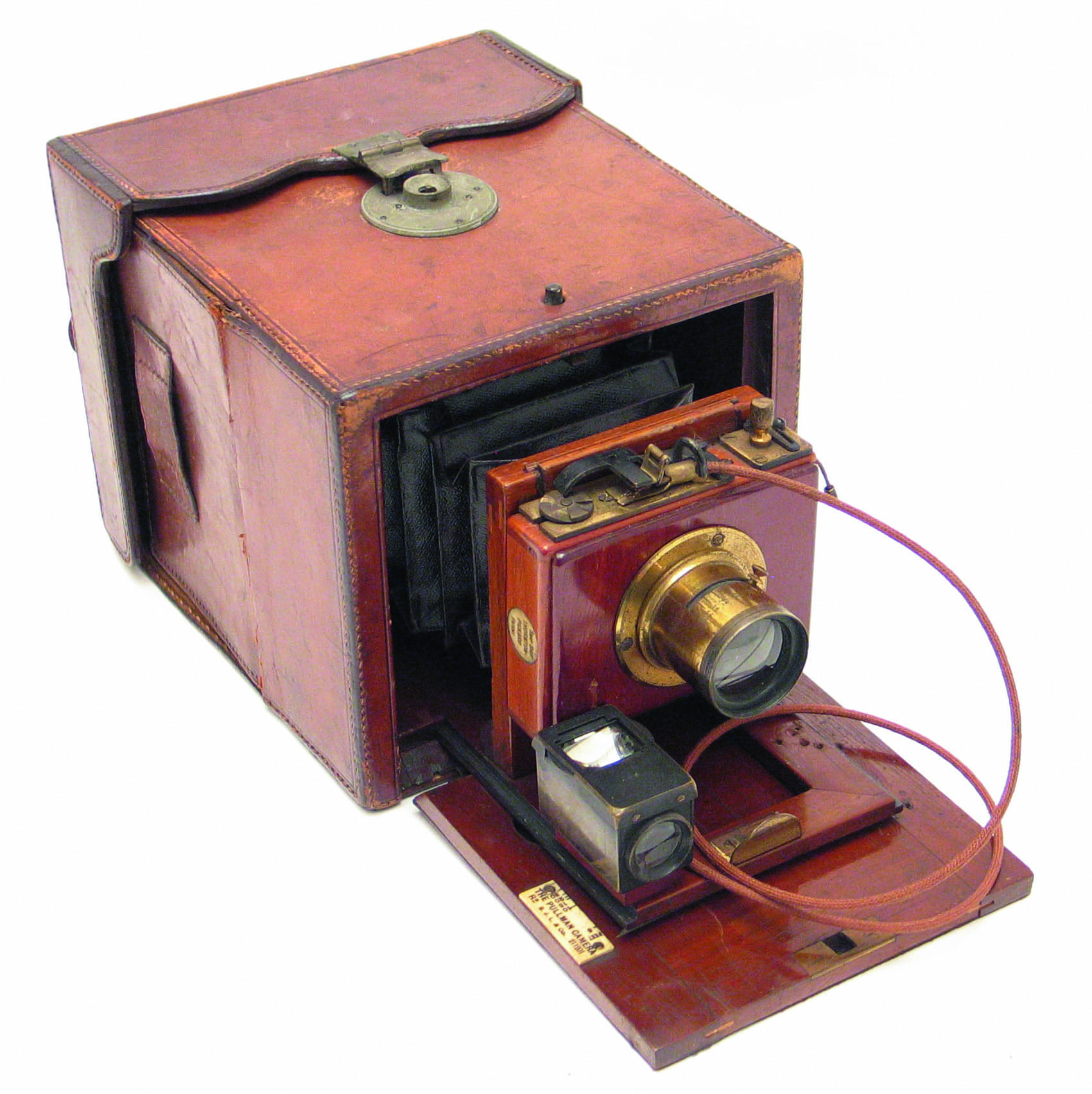

Pullman Detective Camera – c.1894

Image © Peter Loy (www.peterloy.com)

Detective cameras were typically box-form, often with rudimentary or no viewfinders, but could be loaded (charged) with up to a dozen plates that could be changed quickly. Many were dull black boxes, but this Pullman is disguised as a saddle-leather case until opened, revealing the Victorian innards. Sometimes they were used for ‘street’ photography but their main purpose was to avoid unwelcome attention when it was not in use.

It would be hard to be completely unobtrusive when actually taking a picture with this one.

Leica – 1925

Although at least a dozen 35mm cameras had been on the market before the Leica (originally Leca – at least one ad exists from before they changed the name), none was as well integrated. Even with the grainy films of the 1920s, quality was good enough for postcard-sized enlargements – and remember that in those days, the usual way to get a postcard-sized print was from a postcard-sized negative. The Leica illustrated two things. First, you need the right idea at the right time, and 35mm was an idea whose time had come. Second, you need to integrate as much of the existing technology as possible into a camera that is easy and convenient to use.

Kodak Autographic 3a Special – 1914

Kodaks just kept on getting better and better, and more feature-packed, but also often bigger. In 1894 ‘cartridge’ (roll-film) loading meant that you no longer had to send the whole camera back to the factory for processing, and also introduced the option of home processing. In 1914 Eastman had paid Henry J. Gaisman $300,000 for the rights to the Autographic system (see text). The Autographic 3a Special, featuring cartridge loading, Autographic film and a coupled rangefinder based on 19th century artillery technology – was the world’s first series-production camera with a coupled rangefinder. It took 122 film for the 3½ x 5½inch (6 x 14cm) ‘postcard’ format.

Rolleiflex – 1928

Arguably the Rolleiflex was to roll-film what the Leica was to 35mm: a superb combination of precision and convenience. On the other hand, the original Rolleiflex gave six exposures on 117 film, with knob-wind, red-window film counting and separate shutter-cocking. The Rollei TLR as we normally think of it appeared in 1932: the model K2 was a 12-on-120 camera where a single crank wound on the film and cocked the shutter. The original Tessars were f/4.5: f/3.5 was another 1932 introduction. Crank advance, automatic frame counting (after the first frame, had been set in a red window) and the f/2.8 Tessar first appeared on the ‘baby’ Rollei (4 x 4cm exposures on 127 film) in 1931.

Kine Exakta – 1936

Prototypes of the Russian ‘Sport’ may have preceded the Kine Exakta as the first 35mm SLR, but the Exakta was almost certainly the first to market. Both relied on waist-level finders with powerful magnifiers for focusing, but until right-way-up, right-way-round eye level focusing appeared, the SLR was always going to play second fiddle to the rangefinder camera. Even with a pentaprism, though, early SLRs had manually-set diaphragms, leading to dim images, and mirrors that stayed up after the picture was taken.

Robot – 1934

Image © Peter Loy (www.peterloy.com)

Image © Peter Loy (www.peterloy.com)

Integral motor drives have been commonplace for only 20-30 years, but first appeared in 1898 on the Le Pascal and then in 1921. The small and astonishingly heavy Robot used spring drive but was limited to 24 x 24mm by the shutter design. It was one of the few successful 35mm cameras of the 1930s and 1940s not to accept standard film cassettes. Nor did it acquire a coupled rangefinder until 1955, though it had accepted standard cassettes (with rewinding) since the 1952 Robot Star. Used for surveillance in banks, they were also used by the Luftwaffe, by West German speed cops, and the East German Stasi.

Contax D/Contax S – 1949

The ‘D’ and ‘S’ differed only in their focusing screens and were the world’s first pentaprism-equipped 35mm SLRs. In 1948 it was still unclear quite how dead the dead hand of Communism would be: both the workforce (including the designers) and the buying public assumed that things could return to business as usual in the pre-1939 mould. Note, though, the knob film wind (the Exakta had a lever a dozen years before). And, of course, the mirror

stayed up after the picture was taken.

Post-war austerity (don’t British governments love austerity?) meant that Contax reflexes were hard to come by in the UK but in the United States they were advertised for $475.

Gamma Duflex – 1948

There are many arguments against centralised, planned economies, and the Gamma Duflex is a minor but shining example. Based on a variety of patents and built in tiny numbers in Hungary in the late 1940s, it was the world’s first SLR to have eye-level, right-way-round viewing, an instant return mirror and a fully-auto diaphragm. Later prototypes used a conventional pentaprism. But as the (by now East) German camera industry began to get back on its feet, centralised planners decreed that the Duflex was not needed. German nationalism must have played a part, along with Russian contempt for the Hungarians, who had managed to back the losing side in WW I & II.

Hasselblad 500C – 1957

Roll-film SLRs were nothing new, and nor were compact Hasselblad SLRs. But electronic flash was increasingly popular, and the Compur shutter of the 500C allowed sync at all speeds. Although the Rollei TLR remained at least as popular in the field, the precise framing, interchangeable lenses and backs, and far better close-up ability of the Hasselblad all combined to make it far more desirable for many professional applications.

Nikon F – 1959

Image © Peter Loy (www.peterloy.com)

Image © Peter Loy (www.peterloy.com)

The Nikon F put everything together: rapid lever wind (with motor-drive option), instant return mirror, auto-diaphragm lenses, single shutter speed dial with a full range of speeds, interchangeable viewfinders and quick, easy bayonet-mount lens changing. Its nearest rival was probably the 1953 Praktina, but only when equipped with a motor drive (to get the instant-return mirror). The F was a boxy, brutal machine, but nearly indestructible and equipped from the start with a wide range of first-class lenses. Astonishingly they managed to progress from a coupled, clip-on selenium meter in 1959 to a through-lens meter built into the interchangeable pentaprisms, the original Photomic T-head of 1965.

Canonet – 1960

It’s a boring little point-and-shoot; something that few keen amateurs would give a second glance. Except… It was probably the world’s first modern auto-exposure camera, where you could set any shutter speed at any film speed, and the camera would choose the aperture for you. Clearly a waste of time for anyone who knew what they were doing. Then ask yourself how many cameras do not offer exposure automation today. Time and again, features that were dismissed at their introduction by serious photographers have found their way into the mainstream. One of the main drivers of progress has been manufacturers adding unnecessary or idiot-proof features to make photography easier.

Rollei 35 – 1966

In the 1950s and 1960s, as films grew faster and sharper and less grainy, the original single-frame movie format of 18 x 24mm appeared in more and more cameras. Olympus PEN series cameras are probably the best known. They were pretty much killed off by the Rollei 35 (later B35 model pictured here): full-frame quality, in a camera that was about the same size as many half-frames. Admittedly it was only scale focus and the layout was weird, but astonishingly, substantially the same camera is available today, though at a very high price. Its original introduction and its continued existence are proof that in any era, there are always people who want something different – and are prepared to pay for it.

Konica Autoreflex T – 1967

This is yet another of those cameras that put together existing technologies to make something new and important: a paradigm for all later cameras. Through-lens metering had been introduced in a production camera in 1963 (Topcon) and exposure automation with through-lens metering first appeared in the Contaflex Super BC in 1965 – but the Super BC had a leaf shutter and interchangeable front lens groups, instead of a focal plane shutter and proper interchangeable lenses. The Autoreflex T was a through-lens version of the Autoreflex of 1965, which just to add to the fun had offered switchable 18 x 24mm and 24 x 36mm formats.

Konica C35 AF – 1977

Like the 1960 Canonet earlier in the time-line, this is at first sight a boring little generic 35mm point and shoot – except for one unique feature, in this case autofocus. Although Leitz had been working on autofocus since about 1960, they were beaten to the marketplace by the C35 AF. Like automatic exposure, autofocus was widely dismissed by ‘serious’ photographers as being something that nobody needed; and like auto-exposure, it has since wormed its way into the vast majority of cameras sold today. The 1978 Polaroid SX70 was the first SLR to offer autofocus, with a sonar transponder, but because it was an integral-film Polaroid camera it was easy to dismiss it as a novelty.

Sony Mavica – 1981

As early as 1843, Alexander Bain had designed a means of transmitting images by telegraph; Shelford Bidwell’s Scanning Phototelegraph of 1881 could send recognizable photographs; and the Mavica (sometimes held up as the first digital camera) was in essence a single-frame video camera, recording low-resolution images (490×570 pixels) on floppy disks. But often, it’s as vital to know what doesn’t work, as what does.

Kodak DCS – 1991

With a searing 1.3 million pixels, the DCS was introduced 15 years after Steve Sasson made the world’s first modern digital camera and failed to reach the minimal standard he had set for consumer digital cameras: 2 million pixels. However, speed trumped quality for newspapers, and most early adopters were press photographers. Few others could have afforded them, anyway: the successor to the DCS, the 6-million-pixel DCS 460 (1994) listed for $28,000. The technology advanced to include later versions such as the 2002 Kodak DCS Pro 140 (pictured here). Until well into the 21st century, digital cameras could not touch film for a combination of price and quality. Exactly when (and whether) digital cameras became serious competitors for film is still being debated.

J-Phone – 2000

Put yourself in the position of a loyal AP reader in 1900, looking back over the 16 years since the magazine had been launched. Advances in photography had been staggering. Cameras were easier to use than ever before, delivered better quality, and were far more ubiquitous. Everything was so easy that concerns were being raised about young men taking candid pictures of young women: not only candid, but perhaps revealing a glimpse of ankle. Now, from the viewpoint of 2014, consider that 16 years ago this (rather primitive) camera phone, the first of its kind, was still a couple of years in the future; and think about the camera phones of today.

To read Roger Hicks article on how the advancements in camera technology in the past 130 years helped move the art of photography forward, get the 130th anniversary issue of Amateur Phtogrphapher.

See what’s in the latest issue or download a digital version today.