We all know that smartphones can now take high-quality images, with the option to fine-tune them even further if you shoot raw, but scientists have now found some intriguing ways to extract much more data from phone shots.

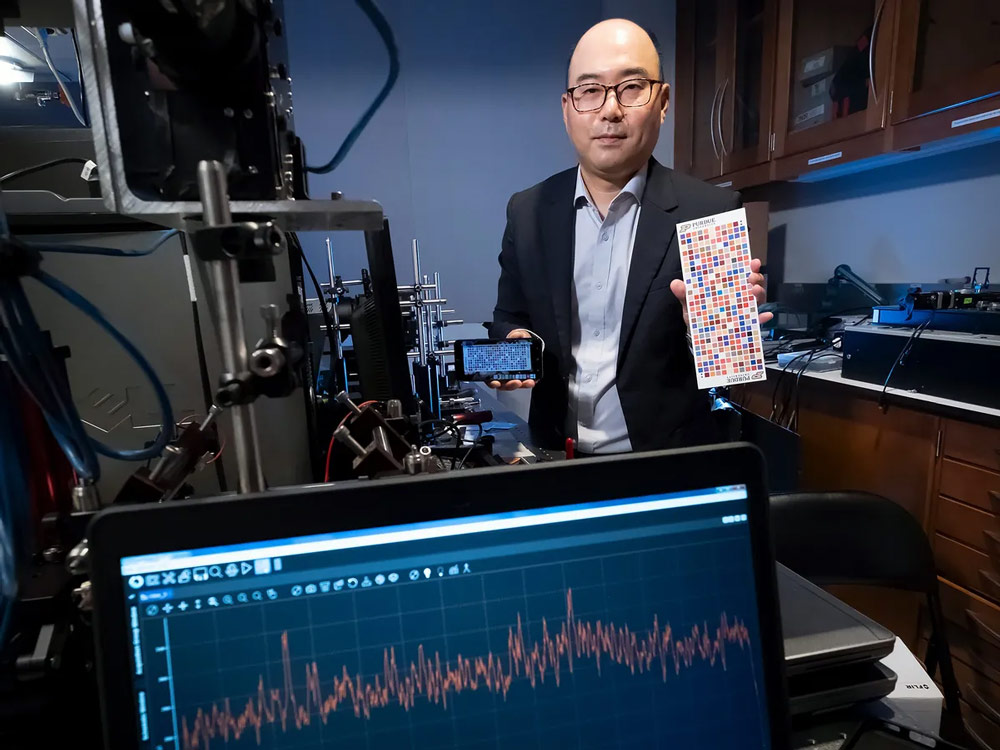

Boffins from Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana, have discovered a straightforward way for everyday smartphone cameras (both iPhone and Android) to work as a hyperspectral sensor, by placing a card with a chart on it in front of the phone.

Put very simply, ‘hyperspectral’ means that a the pixels in a smartphone sensor can pick up many more bands of the electromagnetic spectrum than the human eye, which is only sensitive to red, green and blue in the visible range. Smartphone camera sensors, however, are potentially hyperspectral in nature.

“At the heart of this work is a simple but powerful idea – a photo is never just an image,” says Semin Kwon, a postdoctoral research associate of biomedical engineering at Purdue University. ‘Every photo carries hidden spectral information waiting to be uncovered. By extracting it, we can turn everyday photography into science.’

Hyperspectral could go hyper

This revelation has some interesting applications, with the researchers suggesting that chemicals identified in photos could be used in medical diagnostics, distinguishing authentic versus counterfeit products (dodgy Scotch whisky vs the real thing, for example), monitoring air quality, and non-destructive analysis of pigments in artwork, to reveal more about great masters.

The scientists at Purdue University have come up with a special colour reference chart that can be printed on a card, which is then placed in view of a smartphone (see above).

Meanwhile a newly developed algorithm analyses smartphone pictures taken with this card, accounting for variables such as lighting. This approach can extract hyperspectral data from raw images with a sensitivity of 1.6 nanometers of difference in wavelength of visible light, comparable to scientific-grade spectrometers.

“In short, this technique could turn an ordinary smartphone into a pocket spectrometer,” added Young Kim, professor of biomedical engineering at Purdue.

See the original story on IEEE Spectrum for more, but it’s an interesting development, suggesting many more applications for smartphone photos than just Instagram or other social media platforms.