Amateur Photographer verdict

With its vast zoom range and impressive close-up capability, the Sigma 16-300mm F3.5-6.7 DC OS is the most versatile lens you can buy. It’s great for travel or when you don’t want to change lenses.- Huge, and incredibly versatile zoom range

- Excellent close-up capability

- Fast, quiet, accurate autofocus

- Decent image quality

- Dust- and splash-resistant construction

- AF tracking isn’t as good as most telephoto zooms

- Large compared to older DSLR superzoom lenses

The Sigma 16-300mm F3.5-6.7 DC OS is an optically stabilised ‘superzoom’ lens for APS-C mirrorless cameras. Its 18.75x zoom range is the broadest of any lens currently available, and equivalent to 24-450mm in full-frame terms. Its close-up capability is impressive too, with the lens capable of half life-size magnification. This means it can tackle almost any imaginable subject, including landscapes, sports, macro and wildlife photography.

Sigma 16-300mm F3.5-6.7 DC OS at a glance:

- 24-450mm equivalent zoom range

- Half life-size magnification at 70mm

- Minimum focus 17mm – 105cm

- 74mm diameter x 121mm length; 615g

- Canon RF, Fujifilm X, Sony E, L-mount

At $769 / £599, the Sigma also looks remarkably affordable, given its massive range. It’s in the same price bracket as both shorter-range APS-C superzooms from the camera manufacturers themselves, and optically stabilised 70-300mm lenses. So you’re not necessarily paying much extra for its much broader wideangle range.

The Sigma 16-300mm is also similar in price to its closest competitor, the Tamron 18-300mm F/3.5-6.3 Di III-A VC VXD, which costs $699 / £529 but can’t deliver the same wideangle view. You can see the sheer breadth of that 16-300mm range below.

Historically, enthusiast photographers have tended to shun lenses of this type, as their optics are inevitably compromised compared to using two zooms that cover the same range. However, one of the biggest advantages of mirrorless systems has turned out to be the ability to make ambitious lenses like this, with much higher image quality than we ever saw from their DSLR equivalents. So how does Sigma’s superzoom measure up in real-world use?

Features

Looking first at the optics, Sigma has employed 20 elements in 14 groups, including 4 aspherical elements, 4 made from super-low dispersion (SLD) glass, and 1 from ‘F’ low dispersion (FLD) glass. Together, these aim to deliver sharp images across the full zoom and focus range, while minimising colour fringing due to chromatic aberration.

Focusing is driven by Sigma’s High-response Linear Actuator (HLA) motor, which promises fast and accurate autofocus. The minimum focus distance ranges from 17cm at wideangle to 105cm at telephoto. However, the maximum magnification of 0.5x is delivered midway through the range, at the 70mm setting.

Sigma says focus breathing is suppressed optically, making the lens suitable for video as well as stills. Optical stabilisation is built in, and rated to deliver 6 stops of shake reduction at the wide end, dropping to 4.5 stops at telephoto.

The barrel boasts dust- and splash-resistant construction, bolstering the lens’s credentials for shooting outdoors in less than perfect conditions. Meanwhile the front element features a water- and oil-repellent coating to help keep it clean of fingerprints and raindrops.

Sigma has employed an aperture diaphragm with 9 curved blades, with the aim of delivering attractively blurred out-of-focus backgrounds. Filter users are catered for via a 67mm thread, and a petal-shaped hood comes in the box.

Build and handling

Size-wise, the 16-300mm F3.5-6.7 is rather large for an everyday standard zoom, although it’s still perfectly sensible given its long range. It measures 73.8mm in diameter and 121.4cm long, and weighs 615g. That’s very similar to both the Tamron 18-300mm f/3.5-6.3 and telephoto zooms such as the Fujifilm XF 70-300mm F4-5.6 R LM OIS WR. It is, however, rather longer and heavier than DSLR superzooms with a similar telephoto reach typically used to be.

The design has a rather distinctive look, with three cylindrical sections that increase in diameter as you move away from the camera. Sigma has used its signature Thermally Stable Composite (TSC) plastic for the outer barrel, which helps keep the weight down. Overall, the lens feels quite nicely made and robust.

A broad zoom ring is placed at the front and requires only a quarter-turn to travel through its entire range. The lens extends quite dramatically in the process, by about 8.8cm in total. But impressively, there’s barely any wobble or play in the front section, even at full zoom.

Sigma has also managed to strike a good balance between making the zoom action sufficiently firm that the lens won’t extend under its own weight, and keeping it just smooth enough to enable accurate composition.

Should you wish to fix the lens to its shortest length for transport, a zoom lock switch is provided. It’s placed on the lower left of the barrel where it’s easy to reach with your left thumb.

Immediately behind the zoom ring, there’s a fixed ridged section that provides useful grip for mounting or removing the lens. The manual focus ring is placed on the mid-sized section closer to the camera, and rotates smoothly with no end stops. Finally, the rear barrel section is kept as slim as possible, to avoid jamming your fingers up against the handgrip on smaller camera bodies.

Unlike many telephoto zooms, though, you won’t find any switches to set focus mode or optical stabilisation. Instead, you have to control these from the camera. Fujifilm users should note that there’s no aperture ring, either, so you change this setting using an electronic dial on the camera body.

Unusually, I was able to test both Sony and Fujifilm versions of the lens, on three different cameras: the Sony Alpha A7R V (in 26MP APSC crop mode), the Fujifilm X-T5, and the smaller, rangefinder-style Fujifilm X-E5. Unsurprisingly, I found it handles best on the SLR-shaped cameras with larger handgrips. But I was also pleasantly surprised by how well it worked on the X-E5 – here you essentially just hold the combination by the lens itself. I didn’t spot any significant performance difference between the E and X-mount versions.

Autofocus

The first compromise you’ll discover when using the 16-300mm lies with autofocus. In most situations, it’s absolutely fine; indeed with static or slowly moving subjects, it’s fast, silent and accurate, making it dramatically better than SLR superzooms of old. However, it’s no match for most telephoto zooms when it comes to tracking moving subjects.

That’s not to say you can’t shoot anything that moves, though. I found that given a little time to pick up the subject, the lens could usually achieve accurate focus for the first few frames. It could also keep up quite well with relatively slow and predictable objects. But what it couldn’t do was maintain focus on rapidly oncoming subjects, such as birds in flight. Instead, I got a lot of out-of-focus shots, with the occasional, essentially lucky in-focus one in between.

There are some tricks you can use to improve your hit-rate here, though. It’s probably best not to set your camera to its highest shooting speed, but instead select something in the region of 5fps, to give the lens more time to shift focus between frames. You can also set the AF system to Focus Priority (rather than Speed Priority) in AF-C mode. Your continuous shooting rate will drop, sometimes very dramatically, but a much higher proportion of your shots will be in focus.

If you ever need to use manual focus, it works very well. Turning the focus ring will automatically engage the camera’s usual focusing aids, such as a distance scale, magnification, or peaking. I found the action to be nice and responsive too, making it easy to achieve sharp results.

Performance and image quality

How you take to the images created by the Sigma 16-300mm f/3.5-6.7 will depend to a great deal on how you normally assess your files. If you’re the kind of person who judges lenses based on test-chart results or brick wall shots, and who wants pin-sharp corners on a 40MP sensor (or even 26MP), then it probably won’t be for you. But if instead you prefer to look at your images as a whole, perhaps after a little cropping, chances are you’ll be quite happy.

I shot around 800 photos while testing the lens across three different cameras. It’s clear that technically, you don’t get quite as good results as you would from using a pair of zooms to cover the same range, for example the Fujifilm 16-80mm f/4 and 70-300mm f/4-5.6 for X-mount users. The lens performs best in the middle of its range, but gets noticeably weaker at the extremes.

Most obviously, images look a little soft towards the telephoto end, especially wide open and beyond 200mm, although they improve on stopping down. Things aren’t helped here by the fact that you’ll often be juggling using marginal shutter speeds against boosting the ISO, even in good light.

Corner detail can look also somewhat soft, especially at wideangle, and sometimes I saw some residual colour fringing from uncorrected chromatic aberration. However, thanks to the use of integrated software corrections, you won’t see any significant curvilinear distortion. Instead, straight lines along the edges of the frame are rendered as they should be. Vignetting will normally be suppressed by the camera body.

But here’s the thing. While I could pick out these flaws when examining files at 100% onscreen, they weren’t necessarily so evident when viewing images full-screen on my 24in monitor (which is roughly equivalent to a 12 x 18in / A3+ print). Instead, my images generally looked clean and nicely detailed.

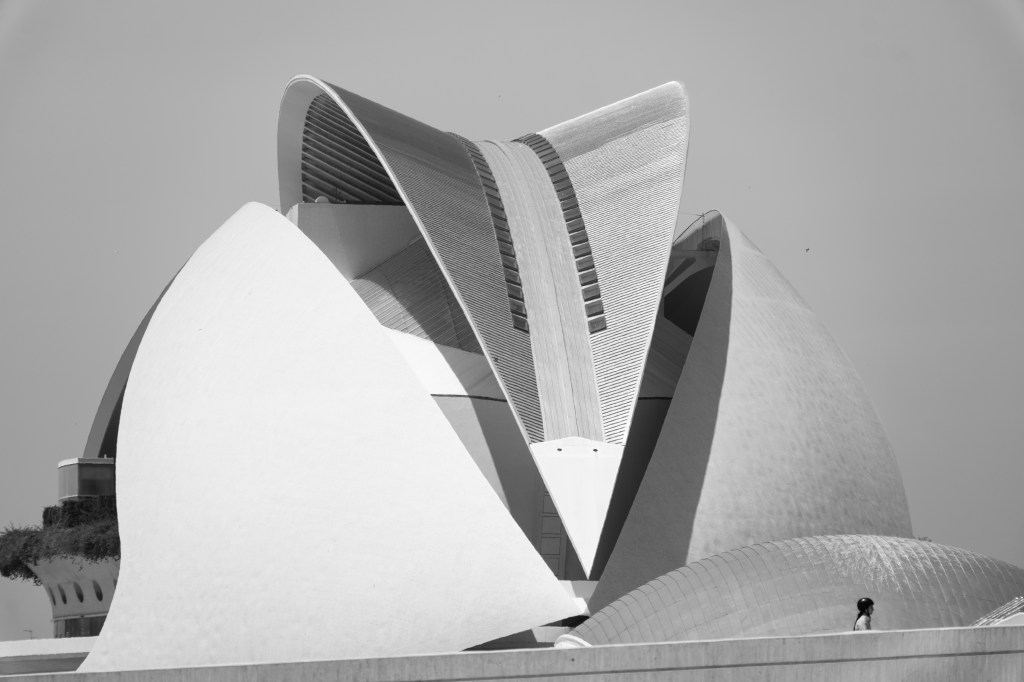

In fact, other factors will often limit image quality more than the optics. For example, when I was shooting cityscapes in Valencia on a hot summer’s day, heat haze and atmospheric distortion was by far the limiting factor to sharpness.

I was impressed by how well the lens performed for close-up shooting. At 70mm, you can photograph a subject as small as 47 x 31mm. However, this does require the front of the lens to be very close to the subject, which risks getting in your own light and disturbing subjects such as insects. When you’re this close, you’ll also need to use fast shutter speeds hand-held to avoid blur, as image stabilisation gets much less effective than at longer distances.

Often, it’ll make sense to zoom a bit longer and take a slight hit on magnification, in return for a longer working distance. It’s a shame, though, there isn’t any reminder marked on the zoom ring of where the maximum magnification is achieved.

One other drawback I noticed came with respect to the optical stabilisation. In my hands, it was less effective at ‘locking down’ a composition at long focal lengths, and visibly ‘jumpy’ in comparison to my Fujifilm 70-300mm. However, this didn’t necessarily correspond to a significant decrease in actual stabilisation effectiveness, with both lenses capable of giving a good proportion of acceptably sharp images down to about 1/30sec at 300mm.

Sigma 16-300mm F3.5-6.7 DC OS: Our Verdict

Lenses like the Sigma 16-300mm F3.5-6.7 DC OS tend to polarise opinion among photographers, with some embracing their remarkable versatility, while others bemoan the perceived image-quality hit compared to shorter zooms. Personally, I take a pragmatic view. Sometimes, the ability to cover a massive zoom range without changing lenses can be invaluable – most obviously, when travelling with friends or family. And personally, I’d rather celebrate the many things it can do, than complain about those it can’t.

What’s really struck me about the Sigma 16-300mm is how much better it is than similar lenses from a decade ago. Not only does it cover a vast focal-length range, it’s also great for close-ups; it really can try its hand at pretty much anything. Images generally look clean and decently detailed, and the autofocus is silent and snappy. The price is very reasonable, too.

Of course, we have to acknowledge that with its small maximum aperture, this lens does have its limitations. It’s not going to deliver much in the way of background blur when shooting portraits, unless you can step a long way back and zoom in, and it won’t be the best choice for shooting in low light. If these things are important to you, it would make sense to add a fast prime or two, with Sigma’s excellent F1.4 DC series being the obvious choice.

It is also still the case that you’ll get better results if you’re prepared to carry two lenses covering the same range. So if you’re already happily doing that, I’d stick with what you’ve got. But if you’re an APS-C user looking for the most versatile all-in-one lens available, the conclusion is simple – go out and buy the Sigma 16-300mm F3.5-6.7 DC OS right now.

Follow AP on Facebook, X, Instagram, YouTube and TikTok.

Sigma 16-300mm F3.5-6.7 DC OS full specifications

| Price | $769 / £599 |

| Filter Diameter | 67mm |

| Lens Elements | 20 |

| Groups | 14 |

| Diaphragm blades | 9 (rounded) |

| Aperture | f/3.5-6.7 – f/22-45 |

| Minimum focus | 17-105cm |

| Length | 121.4mm |

| Diameter | 73.8mm |

| Weight | 615g |

| Lens Mount | Canon RF, Fujifilm X, Sony E, L-mount |

| Included accessories | Hood, caps |