Certain photographers become intrinsically linked with a particular place. Ansel Adams and Yosemite, Weegee and New York, Brassaï and Paris… I realise, as I walk through my home city, which is sparkling in the sunshine and with the anticipation of the annual festival, that Roger Bamber’s connection with Brighton and Hove is every bit as significant. Over some 50 years, he worked the seafront, the streets and the environs of this dynamic place, turning his eye to the quirks of its inhabitants in a way that has never been replicated.

Before his death in September 2022, Roger was working on a book and accompanying exhibition. It’s this show, at Brighton Museum & Art Gallery, that I am on my way to see – and it’s here that I meet journalist Shân Lancaster, Roger’s partner and wife of nearly 40 years. They first met when they worked at The Sun and collaborated on many stories over the years. ‘Roger had always meant to do a book,’ Shân says. ‘Time was getting on and he hadn’t been well. When we got the publishing deal, the first thing he did was ask the museum if they could do an exhibition. They immediately said yes.’

Born in Leicester in 1944, Roger had a lifelong fascination with trains and as a young boy he would go on trainspotting excursions with his father. There was a family camera but he was only allowed to use it when his dad didn’t want it. Roger was more interested in graphic design and technical drawing – an influence that can be seen across his photography – but at the age of 12 or 13, he got a paper round. ‘He often got to the newsagent early, while they were sorting the papers out,’ Shân explains. ‘He’d look through them and wonder how the pictures were taken and why they’d been chosen. He’d say to himself, “That one’s better than that one,” so in many ways was teaching himself about photography.’

Precise approach

Anyone who has ever worked with Roger on a story, or who has been photographed by him, can testify as to his exacting approach. ‘Excruciating,’ as Shân puts it. And although he was renowned for this illustrative style of photography, he in fact cut his teeth on the hard stuff when he was taken on by the Daily Mail at the age of around 20. He found himself in an environment that meant he had to get the shot, no matter what.

‘He was the youngest on the staff by miles,’ says Shân. ‘He’d come from a graphic background, taking pictures of trains and composing very carefully. But the minute his feet hit the ground on a newspaper, he realised what a rush it was to bank the picture. He loved the competitive element of it. But he was one of the few people I met who could combine having the sort of eye and the patience to construct a perfect picture with being absolutely able to drop everything and smash straight in and still get a brilliant frame. Everyone loved working with him because he was great on hard news – most people dreaded working with him on features because he was so bloody nitpicking!’

She cites one example where he photographed sculptor Bruce Williams. Instead of simply placing him next to his laser-cut pieces of work that depicted athletes in action, Roger made him leap over the panels – again, and again, and again… The next day, when he rang Bruce to thank him, the artist was in so much pain he was unable to make it to the phone…

Bamber didn’t only put others in uncomfortable positions, however. He would do it to himself, too, if it meant capturing an image that would stay in people’s minds. There are not only his images taken from the tops of the Severn and Clifton Suspension bridges, but also one taken during an altitude attempt by microlite enthusiast Rod Jenkins. It was only after Roger had lost a 36-exposure roll of film to the wind that he realised his pilot had taken him – on this ‘lawnmower with wings’ – higher than the would-be record-breaker.

All of these images were taken after Roger moved to Brighton in 1973 (to a house overlooking the station – a trainspotter’s dream), and being in the city meant he could travel across southern England in pursuit of a story, but his new home became the focus of his photography and in 1999 the council commissioned him to produce a body of work to support Brighton and Hove’s city status bid.

‘He was given free rein to be as inventive as he liked,’ Shân recalls. ‘He came up with the idea of photographing a person born in each decade leading up to the year 2000. It started with a 90-year-old man playing bowls in Hove and ended with a newborn baby at the hospital. The images were all over the London Underground – everywhere.’ The bid was successful and the University of Brighton subsequently awarded Roger an honorary degree.

It would be easy to think that someone who shot as much film as he did, with only the most minuscule alterations between each frame, is demonstrating a lack of confidence in their vision. But for Roger, it was the reverse. There was a total conviction about the way he worked and a certainty that his response to whatever was unfolding in front of him could be translated onto a piece of film with the utmost precision. Referring to one image in the show, Shân says, ‘On the contact sheet, there’s a whole sequence of almost identical ones, but a great big circle around this one.’ When he’d captured it, he knew he’d captured it.

The move to colour

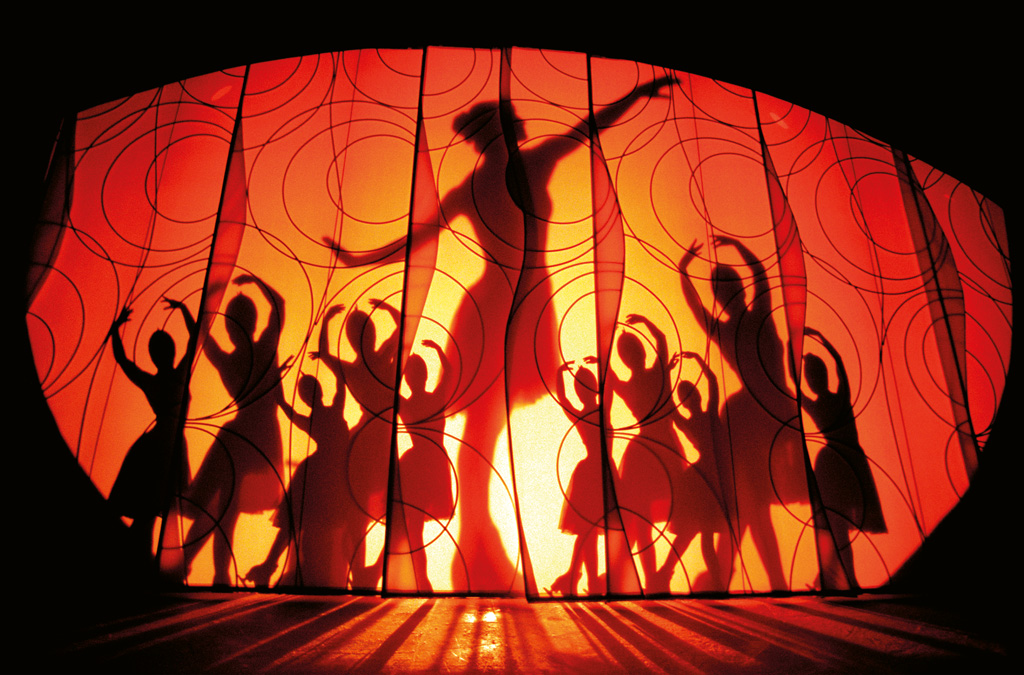

Roger is, of course, known for his black & white work. And if there’s one style that crops up consistently in his work it’s the silhouette – no doubt a throwback to his grounding in graphic design and technical drawing. In many ways, he would analyse a scene not for the ‘thing’ he was photographing, but the shape it was making in the frame. And that applied whether he was shooting a piece of art or a rock star.

However, during his career, the newspaper world made the transition into colour and then digital. I ask Shân whether monochrome was where his heart lay, or whether he didn’t really mind. Her reply is unequivocal: ‘Oh, he really did mind. He was horrified when he was told he was going to have to go colour, and he thought he’d have to rethink everything. And to go digital as well was a massive jump. There were a couple of hiatus years where he was having to get used to the new technology – it was very, very difficult and he practically had a nervous breakdown. But once he’d managed to change gears, he really took to it – and, of course, he was brilliant at it.’

It was partly thanks to the support of the many friends he had made during his career that he was able to make the transition, as Shân explains. ‘He had no side,’ she says. ‘An awful lot of Fleet Street photographers are absolutely impossible – bless them – because they are so conscious of their status and they treat local photography with great condescension, but Roger treated everyone as a friend. He made friends with all the local snappers, so they responded to him and helped. If he’d been more arrogant and “Fleet Streety”, they’d probably have said, “You sink or swim, sunshine”.’

Sadly, towards the end of his life, Roger became unwell and found it more and more painful to walk, and then had a stroke that resulted in the loss of his balance and also the sight in one eye. Lockdown was also very difficult for someone whose life revolved around interactions with others, and Shân paints a picture of a frustrated man who would sit on the doorstep to their small front garden, chatting with any neighbours who passed by. Roger died of lung cancer in Sussex County Hospital, in September 2022, at the age of 78.

On my way home, my attention was again drawn to the preparations for the Brighton Festival, and how Roger would have been giddy with excitement about the photographic potential. His desire to connect with people – to interact, to learn about their passions, to be curious – runs through his 50-year body of work. And in the exhibition and book, which sadly he didn’t live to see completed, we were afforded an insight into his full and fascinating life. There’s his employment card from his paper round as a boy, and a grid of the dozens of press passes that gave him access to the stories that would become his photographs. There is colour, there is black & white, hard news, features – and, of course, his beloved Brighton, in all its sometimes grey, sometimes dazzling, always characterful glory. It’s a fitting tribute to the photographer who the late Guardian picture editor, Eamonn McCabe, who died suddenly only a month after Roger, called, ‘The picture editor’s dream.’

Roger Bamber: Out of the Ordinary is on at Brighton Museum & Art Gallery until 3 September, entry £9 (which includes an annual pass to the museum) visit brightonmuseums.org.uk. The book of the same name is published by Unicorn Publishing Group, price £40.

You can also check out more exhibitions here.

Have you read these articles:

International Portrait Photographer of the Year 2023 winners revealed

10 Reasons why every photographer should shoot weddings

Follow AP on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube and TikTok.