A new exhibition at the Tate Modern, Surrealism Beyond Borders, shows us how surrealism was not just confined to Paris, but was a network that stretched all around the world, says Damien Demolder

I suppose that when most of us think of surrealism, pictures of the lobster-shaped telephones and flying cats of Salvador Dali spring to mind. Those in the know, of course, will realise that the roots of the movement take us back to 1920s Paris. There are the famous names of the movement, such as André Breton, the man who defined surrealism in his Manifesto of Surrealism in 1924, as well as the photographers we may know such as Man Ray, Marcel Duchamp, Brassaï and André Kertész.

For the most part, people associate surrealism with a relatively small band of artists based in Europe, but an upcoming exhibition at Tate Modern intends to expand our appreciation a little more by exposing us to the pockets of surrealists that sprang up all around the globe and to the artists we may not know so well.

It is easy to assume that surrealism happened in a room of about 20 artists in Paris, but Carine Harmand, one of the curators of the Surrealism Beyond Borders exhibition that’s showing until August, explains that surrealism was actually a network of artists that stretched around the globe.

A global network

‘This exhibition is an attempt to expand the understanding of surrealism,’ Carine tells us. ‘Surrealism is generally seen through a Paris-centred lens, but while André Breton was formulating surrealism as a force of personal, social and political liberation, other artists, writers and intellectuals in other places were thinking about the same things – such as in Prague and Brussels.

So we are trying to shift people’s idea of surrealism and show them how much of a movement it was and how these ideas influenced artists and intellectual circles all around the world. The exhibition looks at surrealism in places like the Caribbean, Eastern Europe, Japan and Mexico. These centres of surrealism were completely influenced by each other, and we are trying to show in the exhibition how these networks were truly international.

For example, there were a lot of amateur surrealist photo clubs that developed in Japan, but they were translating texts that had come from Europe and talking about what European artists were doing. ‘As surrealism is rooted in the idea of liberation and the breaking down of social and political conventions, there was quite a lot of impetus for people to share these ideas and to stick together.

Intellectuals and artists were under a lot of pressure in the period during and between the two world wars. When they came together there was an immediate kinship and understanding, and a real driving force to share ideas and express themselves. They organised exhibitions and shows all over the world.

‘Surrealism is a vast area and what we are trying to show in this exhibition is that it isn’t a simple ascetic movement but is a way of thinking and a way to subvert the everyday, to interrogate conventions and political and social systems – and it expresses itself in a wide range of different ways.

Automatism for example is a technique that was really cherished by surrealists because it was a way to delve into the unconscious. The surrealists were really inspired by Freud’s texts and his idea of the unconscious and the value of dreams to reveal what is repressed by social conventions. So surrealist art was trying to find out what is beneath the rational and what you can see on the surface to liberate that power.

Extending this personal liberation of creativity was also coupled with an agenda of political liberation. The first way of seeing surrealism is about the dreams, the unconscious and the liberation of desires, but there is much more to it than that. The values and norms of society were seen as obstacles to creativity, so this way of thinking intended to break free of that.’

Photography in surrealism

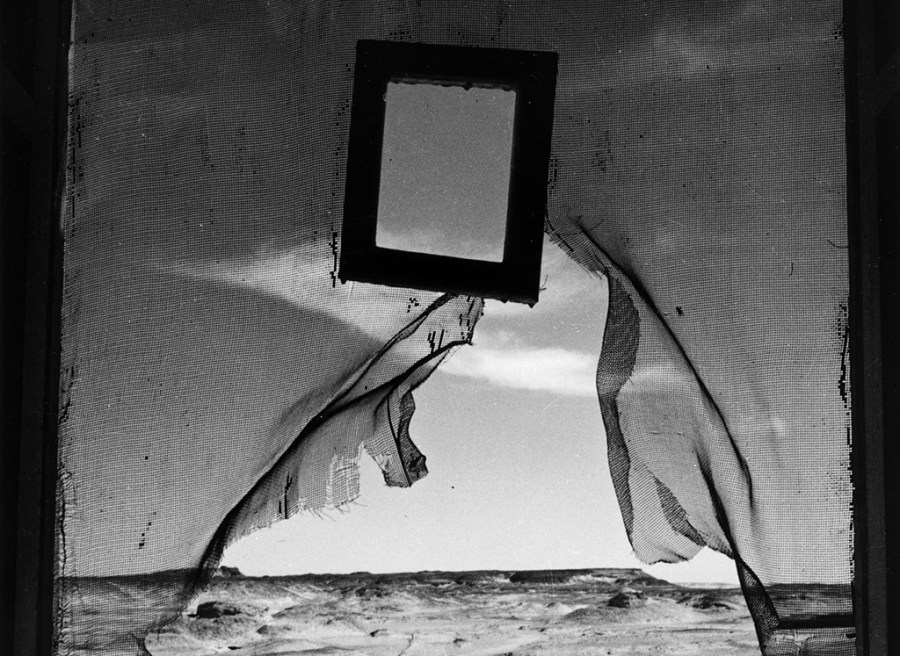

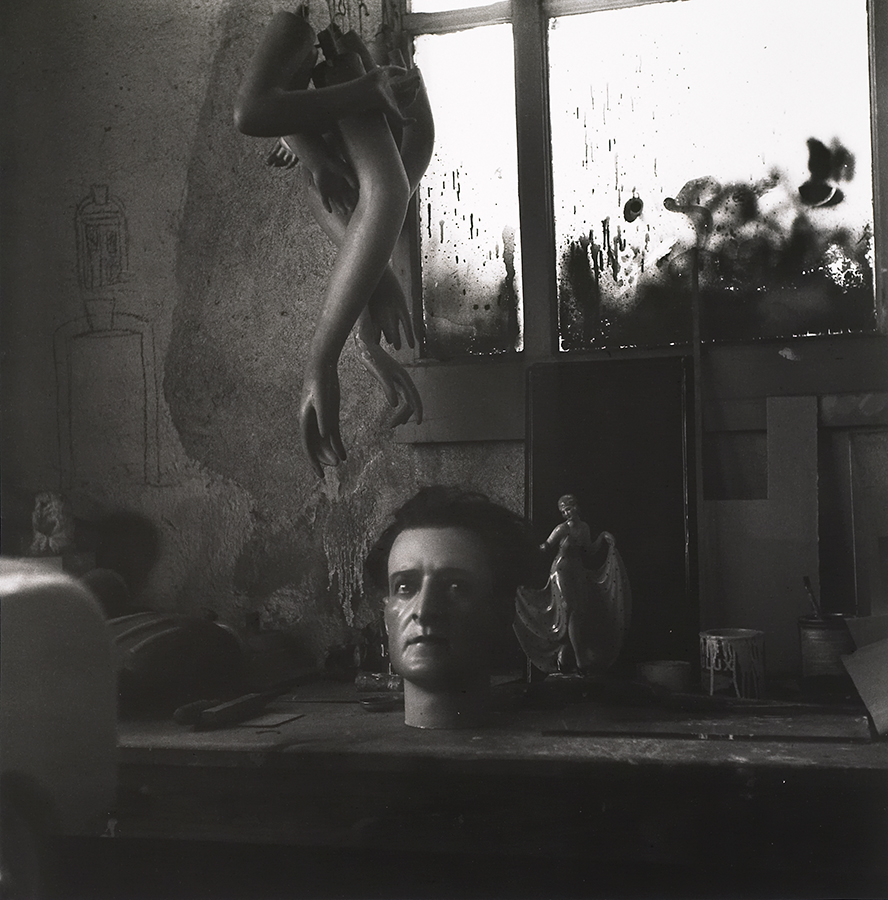

‘There is a section of the exhibition that is given over to photography, in which we explore the idea of the uncanny in everyday life and how the uncanny was so important to surrealists. By “uncanny” we mean a familiar sight that you would encounter in normal daily life but which looks disconcerting and strange.

Photography is a great medium for this, as when you are walking around and see something strange you can just capture it in a way that would be more difficult with other media. ‘In the 1930s-40s, Czech surrealist groups had to be underground as they were seen as expressing dissident ideas against the socialist/communist regime of the time.

So rather than showing pictures that are directly against the war they made pictures that included war damage but in normal everyday scenes in the street so the effect is just uncanny and strange. ‘Other artists used photography in set-up and staged strange scenes instead of pictures taken in the street to get their messages across.

Fernando Lemos was part of the Lisbon group in the 1930s and took some photos of the big market in Lisbon that give us the sense of something really strange, and also quite morbid. He and his group got together to develop ideas and to create collective works that tried to resist the Salazar dictatorship.

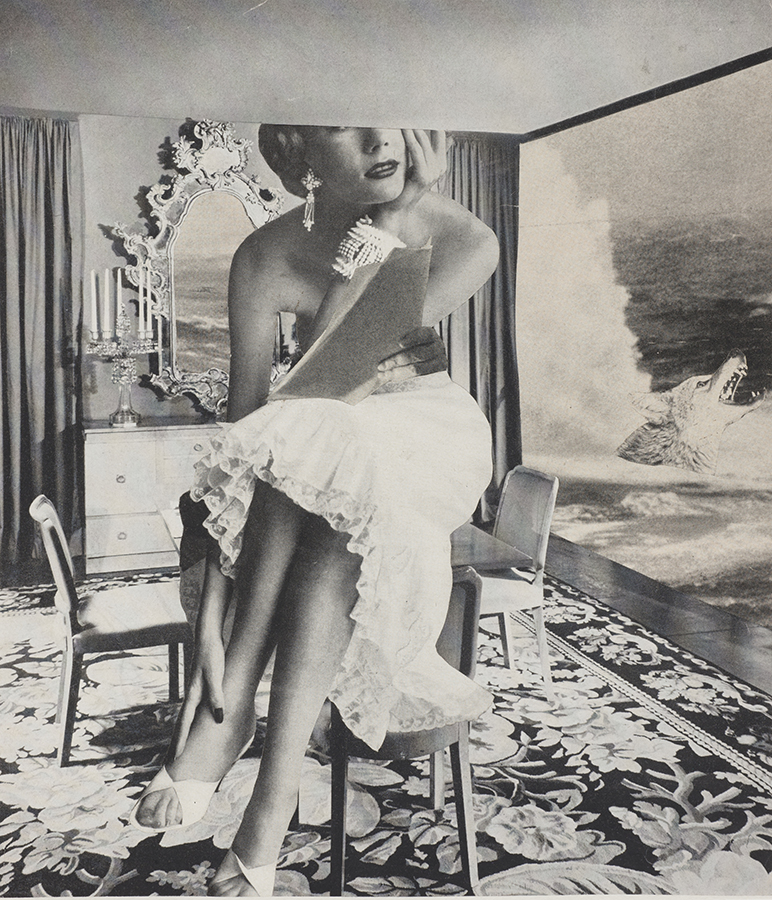

Then there are artists like Toshiko Okanoue from Japan who was making work in the early 1940s and 50s. She created collages of natural and staged photographs from magazines left by US troops after their occupation of Japan between 1945 and 1952. Her collages translate her experiences of post-war Japan with its foreign commodities, references to glamour, the westernisation of Japanese culture and to new political and social rights for women that were only just developing in Japan at that time.

‘Surrealism was a way for artists to explore and experiment with photography as a technique, to reveal the strangeness in life. One of those techniques was solarisation. There are some questions around who really discovered solarisation – was it Man Ray in Paris or Lee Miller who was in his studio?

‘We are also trying to show surrealist artists that are not traditionally so well known in European and American art circles. There are two artists from Korea called Limb Eung-Sik and Haechang Jung. They are both photographers who produced works in the 1940s. Their work is a response the pressures of Japanese colonialism in Korea, so there is a strong sense of morbidity in their pictures. They also compose objects in very strange ways, like a table with a hand coming out of it.’

Surrealism is a surprisingly broad area, and there are so many different ways of expressing oneself through photography under this umbrella – between the uncanny everyday scenes observed in the street to the heavily constructed set-up ideas. Automatism is a big part of surrealism as an art form, and I wondered how, and if, photography fits into this mould.

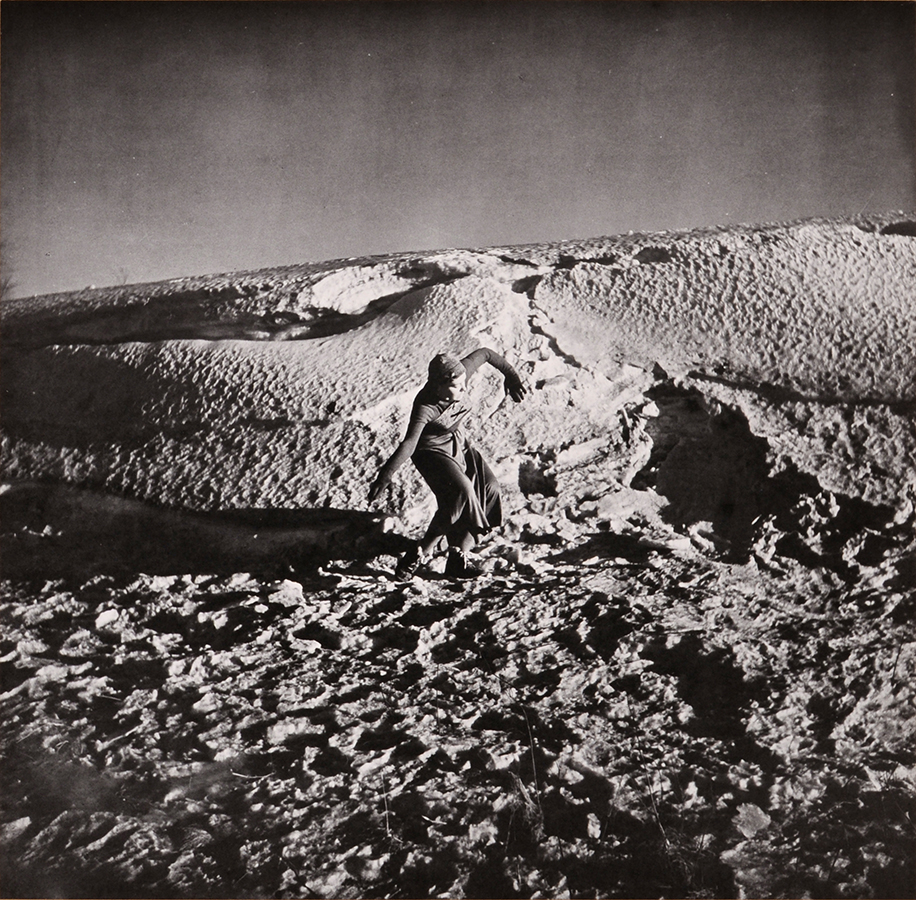

‘I guess it does,’ says Carine. ‘We have examples of how photography was used to record automatism. For example, Françoise Sullivan performed Dance In The Snow to the sound of her feet crushing the snow, and she used photography to record it. But there are surrealist artists who apply paint to photographs in an automatism style so that they don’t know what the end result will be until it is finished.

‘Photography and automatism are hard to connect, though, as taking a picture is a more planned event that leaves much less to chance. Photography is quite different to writing and painting, where it is much easier to let yourself go.’

Abstract protest

A lot of surrealist photography and art is quite hard to understand. Sometimes it takes a lot of looking at a picture to work out what it is about – if, that is, you can at all. Surely, I ask Carine, there must be a better way to communicate your ideas and beliefs about liberation and pushing back at authority than in abstract images that may not deliver your message at all.

‘Was their work meant to be explainable or understood only by other surrealists and likeminded people? It is part of what they intend to do – to have this unsettling view that leaves us not sure what we are looking at. They want to challenge the ways we are taught to look, and to tell us that things aren’t as straightforward as we are led to believe.

So I would say it is effective in that way, and if we have to pause to think more about what an image means then they have achieved what they meant to, which is getting people to stop and question reality.’

I suggest that although surrealist works do make us question things, some would look at a surrealist picture, decide immediately that they don’t get it and move on without having gleaned anything from the experience. It seems they communicate in a language that the rest of the world can’t understand.

‘For a lot of artists, having a vague message was a way of being able to continue their work. In Japan, for example, state censorship was massive, to the extent that in the late 1930s a lot of these photo clubs were dissolved by the government and many artists were put in prison. People had to remove the word “surrealist” from their photo clubs’ titles, but they were still producing surrealist works.

‘In Osaka there is still a surrealist camera club. There was a lot of activity in surrealism in amateur photography before the Pacific War and the thought police were very active in censoring things and suppressing political groups. So these clubs were a way of people getting together to carry on discussions they weren’t able to have elsewhere.

‘They had to make works that were much more subtle and less in-your-face, and which were subversive in a less obvious way just so they wouldn’t end up in jail. Making work that was more difficult to understand, or with a more hidden meaning, was a way to cope with the situation. It was the same for Czech artists as well, who also had to be underground.

A lot of these works weren’t available to the public and they were only shown to other surrealists in their circles. They could show their work in Paris or Mexico, but they couldn’t show them publicly at home, so it completely makes sense that they have this language that only other surrealists could understand. They have hidden messages.

‘They were also exploring techniques, and trying to go against the traditional ways of practising photography. There was a willingness to do new things and to be more modern. So it was in the technique that was surrealist – in the automatism of the technique – not necessarily in what you see in the end.’

Photographers, or artists with cameras?

‘It’s impossible to say who the most important surrealist photographer was, as they all expressed themselves in ways that were relevant to their contexts. But we are also trying to move away from that way of looking at art history and deciding who the most important people were

– which is usually French men doing things in the 1920s.

I can’t say who is the most important photographer, but the best way to understand the importance of photography for surrealism is to look at the diversity of artists and the range of techniques they used to get their surrealist ideas across.’

So many of those shown in the exhibition aren’t photographers at all, I complain. They are painters, writers and musicians who take pictures as well. They aren’t photographers, but people who use photography. They mightn’t identify themselves as photographers, apart from Dora Maar who seemed to only take pictures, but for others it was a sideline. They are surrealist artists first and photographers second.

‘We need to move away from categorising artists by their techniques,’ responds Carine. ‘What is fascinating about these artists is that they have a multi-faceted approach. That was one of the aspects that makes them avant garde is that they didn’t belong to only one medium. And today that is something that still artists do – they paint, sculpt and make video.

Lee Miller exclusively took pictures, but at the end of her life she was a cook, as that was what she wanted to do. She was still a great photographer of the surrealist movement. ‘Lee Miller stands out in the show as a photographer that is very well known, but she is better known as a documentary photographer than as a surrealist.

The show features her book Grim Glory: Pictures of Britain Under Fire, about the Blitz, which she made a piece of war propaganda to get American support of Britain during the Blitz. You could say that this is completely documentary, but the way she photographed the destruction of London has an uncanniness about it.

They aren’t just factual pictures – she paid attention to the way light could reveal things and there’s a sense of strangeness and of the presence of death in all these pictures as well. She is a documentary photographer, but she is definitely influenced by the surrealists in her circle.

‘There are a lot of famous surrealist photographers who aren’t included, such as Man Ray and Dali. There is a Man Ray, but it is a sculpture. We wanted to include the famous artists but we had to make space for the artists who are less well known. Brassaï is included for his Involuntary Sculptures, but then we needed space for Japanese photo books and the artists that the public doesn’t know so much about.

The aim of the exhibition is to show the audience things they don’t know, and to get across the fact that surrealism was a network of people – and beyond the well-known ones there were tons of other artists and interactions that are really interesting to look at.’

How to be a surrealist

‘Surrealism has helped to create an atmosphere of experimentation with technique in modern photography,’ Carine says, summing up her insights into the exhibition. ‘The fact that they were experimenting and merging techniques and using photography to record performance has helped to shape the way photography has developed.

‘If you are an amateur photographer and would like to get into surrealism, you could start by recording strangeness in any kind of way. Whatever you think is strange in what you see or encounter. Recording that would be the first step, and then experimenting with technique.

‘As part of the social media campaign around this exhibition, the Tate will create a hashtag #everydaystrange and get the public to submit their pictures via social media. There will be a big Tate Late event at the end of March and the pictures collected will be shown around the museum – so that’s a great way to get your pictures shown at the Tate.’

Surrealism Beyond Borders runs at Tate Modern until 29 August 2022. Tickets are £18 (free for members). For more information on opening times and tickets, see tate.org.uk

See more exhibitions on display throughout 2022 here.