Peter Dench asked three winners of Astronomy Photographer of the Year 13 to share practical advice on shooting the night sky

Back in September, the Astronomy Photographer of the Year 2021 winners were revealed. Three of the photographers share their tips for capturing the night sky below:

Jeff Lovelace

Astronomy Photographer of the Year 13, Skyscapes winner

Jeff is an award-winning photographer from California, USA. He has telescopes running at a remote observatory in the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Each scope includes a specially designed digital camera cooled to -25°C to help capture images of extremely faint objects, some over a billion light years away. www.jklovelacephotography.com

When I was a child I always wanted to be an astronaut, fascinated by space. I grew up during the period when Star Trek first came out and watched the moon landings. I didn’t do a lot of photography in my teens; I had this rivalry with my brother who really got into photography, which meant in my mind, I couldn’t. What kept me from launching into it was I thought it would be difficult – but I kept seeing this one telescope in the store I thought would be really cool, then I saw a photograph taken through a telescope of Jupiter and I thought, you can do that! That was that, and it’s been a big part of my life ever since.

Astronomy Photographer of the Year, Skyscapes Winner – Luna Dunes. Image taken in Death Valley National Park, California, USA. Sony ILCE-7RM4 camera; Sand and sky: 70mm f/8 lens, ISO 400, Sand: 30-second exposure, Sky: 1-second exposure; Moon: 200mm f/2.8 lens, ISO 100, Moon face: 2.5-second exposure, Moon edge: 1/100-second exposure. © Jeff Lovelace

Nightscape

Wideangle photography, at night with a normal camera and lens, typically with a landscape in the foreground, it’s fairly easy with just a few key settings, some very obvious. Typical exposure times will be from 10-30 seconds, sometimes up to a couple of minutes, so you’re going to need a tripod. A wideangle lens is good, a very fast lens is good, it can be a zoom if it’s a high-quality zoom, F2.8 or faster. You have to know your camera settings and be a reasonably proficient photographer and not have everything on automatic or shutter priority; everything is manual including focusing.

Approach

When I go out to do nightscape photography I have two approaches. One is to go to an interesting area, see what I can find and create in the moment. ‘Luna Dunes’ was the other kind. I had planned in advance, I’d been to those dunes before. I had researched the phase of the moon and weather. I’d even sketched out the image that I wanted.

Apps

I quite often use various apps to find exactly the right spot and time, what angle the moon is going to be at relative to the landscape. The apps that I use are The Photographer’s Ephemeris and The Photographer’s Ephemeris 3D. Together they’re a wonderful tool for planning shots. I might also use PhotoPills and Planets Pro. You can get a star tracker to track the stars as the Earth rotates, or if you’re more analogue you can still use charts!

Where Beginnings End – a focus-stacked timelapse at night comprising of 57 images. Sony A7R IV, 16mm lens, 30 secs at f/4, ISO 6400. © Jeff Lovelace

Rule of 500

Have your lens wide open, and aim it at the Milky Way. There is the rule of 500, which is an old rule anyone can look up – basically you divide the focal point of your lens into 500, and that gives you your exposure time. So, if your full-frame equivalent focal length is 20mm, the 500 rule would suggest that you use a shutter speed of 500 ÷ 20 = 25 seconds.

I use a Sony camera with smaller pixels, so I go with the rule of 250 which is the same thing. The rule of 500 is to avoid exposures that are so long the stars turn into little streaks. You want your stars to be pin-point or close to it, so you don’t want to go beyond the rule of 500 (or 250).

The Shot

When do you know you’ve got the shot? It can happen when I’m in the field. With ‘Luna Dunes’, I knew it in the moment. That being said, I’ve had many of those moments and then I look at it on a larger screen and go, oh no, that’s not so good. The real moment is when you finally do look at a digital image on your computer screen and you know that’s it.

Landscape photographer Ansel Adams is a perfect example, he said something to the effect that great photographs are made not taken. Every image, because of the limitations of the digital camera, needs to be adjusted, the light values have to be adjusted, the brightness, colour values and saturation levels.

Audience

For me the procedure is I put an image on my website first, second Flickr, then Instagram. I output it at different resolutions and see how they do. Flickr is my favourite, its social media but really specifically for photographers. What I’m trying to give them is that Ooh and Aah moment, an experience. I want it to have a touch of mystery, for people to say where is that or what is that little detail… those multi-layer experiences are my favourite.

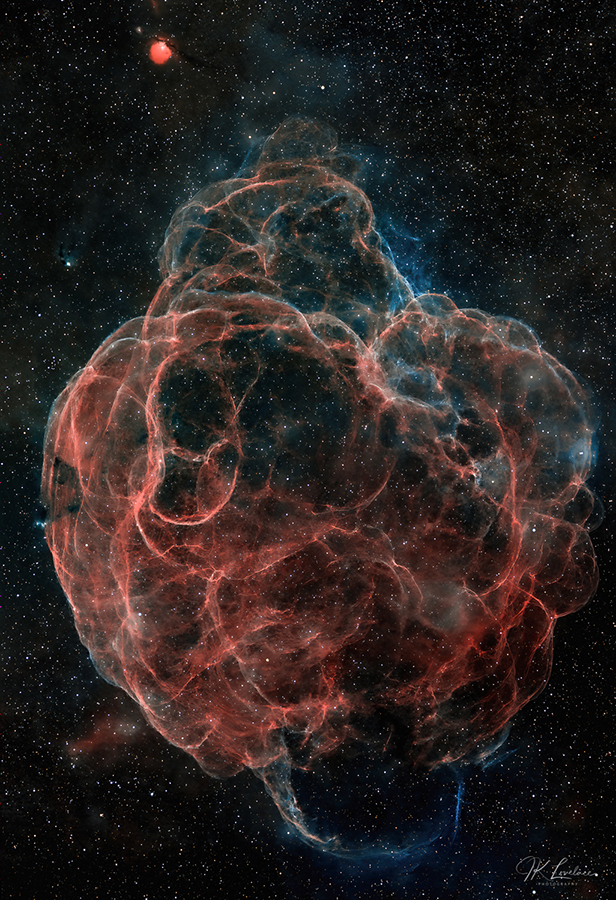

Web of Wisps. Taken with a FLI ML-16070M, a thermo-electrically-cooled camera operating at -25°C. Lens focal length is 381.6mm at f/3.6. The image comprises 153 exposures at two mins each (RGB filters) and 245 exposures at 10 mins each (narrowband filters). © Jeff Lovelace

We are not alone

I hear things. I wear one of those headlamp torches and I’ll look around and see a pair of eyes looking at me somewhere over there. I don’t know what that is but it’s a little creepy. If I am alone, I deal with it in two ways, I make noise and make sure that whatever creatures are out there know I’m here. I may put on a podcast on my iPhone and set it on a rock and occasionally stomp around.

I often shoot with other people; if you have someone within shouting distance your anxiety reduces by about 90%. A friend of mine was once surrounded by a growling snarling pack of coyotes, another encountered a mountain lion, there have been photographers killed by bears, so it’s something to keep an eye on; I’ve been lucky.

Filters

I don’t use filters because I tend to shoot in a very dark location. If you do encounter light pollution, there are a number of brands of light-suppression filters available. Those work or don’t depending on the public lighting or whatever city you’re in. If everything’s lit with LED lights, which are a broad spectrum, they don’t work at all. If you’re in a city with mercury vapour lights or other specific types of light that put out light at a particular frequency, these filters are designed to filter out those so they can work very well.

Noises off

With my regular camera I do multiple exposures. I align them and blend them together, and you get exactly the same picture but it reduces the noise. If you can do 8-16 shots and blend them together you end up with a reasonably noise-free image. The longer you shoot the more noise you get; the darker you shoot the noisier your images get.

The problem with aligning is you have sharp stars and a blurry landscape or vice versa. You have to do some work in Photoshop to combine the two, where you take the foreground from one of the shots and make that the steady foreground then take the sky and put it on top of that. That’s a nice easy trick to get rid of noise.

Deepal Ratnayaka

Astronomy Photographer of the Year 13, People and Space winner

Deepal was born and raised in Sri Lanka, arriving in the UK around 12 years ago. His day job is working as an SAP Consultant specialised in Enterprise Asset Management. Outside of work, he is a dedicated and passionate astro-photographer. www.cosmicdazzle.com Instagram @deepalratnayaka

I’m fond of misty mountains. From a very young age I liked photography. I’ve always been intrigued by astronomy. I picked up a camera after coming to the UK and started doing landscape photography. I felt like something was missing, it didn’t have that oomph! Around five years ago, I started trying astrophotography. The moment I took that very first photograph at night I immediately felt this was the missing bit and then I never looked back. Every time we get clear skies I make an excuse to go out and master astrophotography.

Astronomy Photographer of the Year, People and Space Winner – Lockdown. Image taken in Windsor, Berkshire, UK. Sony ILCE-6600 camera, 8mm f/4 lens; Foreground: ISO 1600, 8-second exposure; Sky: ISO 1000, 844 x 30-second exposures. © Deepal Ratnayaka

Educate yourself

I read a lot and watch YouTube videos and tutorials. Loads of good photographers are there. It’s difficult because you don’t have a methodical way of sitting through a course and then going out. Practically every night I read something about astronomy or astrophotography, gear, techniques etc.

Starting out

Plan a daytime trip so that you get familiar with the location until it doesn’t become a big deal. I would recommend doing an evening shot first. At twilight when the stars come up, you feel like you’re still in the comfort zone. If you reach the place in the evening and stay there until night-time then it’s an easier experience than getting there at night. It calms you and you feel prepared.

Plan ahead

I first go to Google and use the street view and photos available, to find out how the location looks. Apps can show you where the Milky Way lines up at that particular time of the night, All that planning I can do, and I know at 10.30pm I need to be in this place, my camera pointing southwest.

I check the weather for clear skies; one cloud can pass by and ruin your moment. Sometimes no matter how much you plan, when it comes up in the camera it’s different from what you’ve planned. You can either be content with that or try something different, improvise.

Star streaks

A 30-second exposure captures everything at night at that point in time. Then the next 30-second exposure, capture the exact same thing but the sky has moved a bit. So when I superimpose them in Photoshop, every star in there generates a streak, where the land components remain the same.

A vertical panorama showing a comet over Windsor Castle. Sony Alpha 7 III, 100-400mm lens. Sky: 4 secs at f/5.6, ISO 6400. Foreground: 25 secs at f/5.6,

ISO 3200. © Deepal Ratnayaka

Take control

The most common mistake I see is over- processing. When we get on with our day-to-day lives under the sunlight, even when it’s cloudy, you get used to seeing the world a certain way. When you look at night, we can see maybe 20-30% of what the camera sees. A camera’s way of light-gathering capabilities reconstructs a photograph; our eyes take a snapshot.

It becomes surreal, you look at the camera and go, oh wow – it’s a lot more than you can see. It’s very easy to push your boundaries and say I’m going to take the best out of this and you end up seeing a cartoon image which almost takes the beauty of the night sky away because it becomes something different.

Keep trying

There were times over three consecutive weeks where I tried a location in Wales and tried things and none of that generated a decent photo, because the conditions changed and I was not up to the challenge. So I came back to research and study the situation to find out what I had to do.

Precision

I did three tests for the Star Trails image. I had this idea Around Christmas time, the photograph was taken around 20th January. One night when I walked into the kitchen I saw one of the prominent stars reflected in the surface which gave me the idea there’s a picture I can imagine.

Every test had different challenges, it’s a wide shot so tiles on the floor, shiny surfaces, even my router’s light had registered as green spots. Carefully studying my house I eliminated these.

Aftercare

For post-processing itself I can take about one month, every evening spending about 30-45 minutes, because my hardware PC set-up is not capable of handling more than 50 photos loaded at a time. I load all the photos, superimpose them, show me the star streaks, then there are many plane trails that I need to eliminate because I live very close to Heathrow Airport.

Exposures

I want very long continuous lines in the sky (as star trails) to make it pleasing to the eye (quite opposite to small discontinued ‘dashes’). With experience I know that it definitely needs more than five hours of clear sky. Anything beyond is a bonus.

Astro modified

I have a Sony A7S, renowned for its ISO performance, astro-modified by a company in the USA called Spencer’s Camera & Photo. They buy the cameras for the clients from Sony, modify them and ship it. They take out the filters which captures and mimics what we see. If they take those filters out, the camera can capture nebula-specific colours like blood red and pink.

Get noticed

I’m part of a number of astrophotography social media groups and communities. Some of them pick a photo of the week to share. The groups are Star Trails Chasers, Milky Way Chasers, NightScaper and a new one called Landscape Astrophotography – it’s an ideal one for me because that’s what I do. I rarely do just nebulas, stars and galaxies, I like taking photos located from within the Earth.

Göran Strand

Astronomy Photographer of the Year 13, Our Moon Runner Up

A freelance photographer, Göran is based out of Östersund, Sweden. He has domestic and international clients for portraits, commercial shots, events and sports. www.astrofotografen.se or on Instagram @astrofotografen.

In 2012 I quit my job in IT to work as a freelance photographer, and it was the best thing I’ve ever done. My interest in astronomy has developed since childhood and in 2013 and 2016 I was awarded astrophotographer of the year in Sweden.

Astronomy Photographer of the Year, Our Moon Runner-Up – Lunar Halo. Image taken in Östersund, Jämtland County, Sweden. Nikon Z 6II, 14mm f/5.6 lens, ISO 200, 6 x 15-second exposures. © Göran Strand

Go wide

Halos are quite big in the sky so for ‘Lunar Halo’ I used my wideangle 40mm lens. I centred the halo to get the exposure on the halo right. I did some exposure tests and decided on 15 seconds. Because the halo is so big and you want the surrounding area with the trees, I needed to do a six-shot panorama. The halo is okay to do a panorama as it’s only moving a little; with a wideangle lens it’s not a problem.

Panorama no drama

My camera has a built-in shutter release so you press the button and two seconds later it takes the shot. I do the first frame, take the shot, move it. I use a programme called PTGui for stitching them together. It’s a paid-for software but if you’re getting serious with panoramic shots, that is the number one, super-easy to use and really powerful.

When I come back home I copy the images onto my computer, make small adjustments to the raw files, export them to TIFFs and import them to PTGui. Then I do the stitching there and export for final post processing in Photoshop.

Cold comforts

Mirrorless cameras are known for being bad in cold weather because of the battery life but they are getting better and better. My Nikon Z 6II performs great. You can get frost on the front lens so when I’m not shooting I always put the lens cap back on, wear gloves and keep your spare batteries as close to your body and as warm as possible.

Use your nodal

‘Lunar Halo’ is two rows of three images stitched together. Usually when you have the camera on a tripod you have the camera body centred. When you’re turning the camera, you want the centre of rotation at the middle of the lens or you get parallax error. I have a small nodal plate so I get my front lens at the centre of my tripod, so that when I move the lens and do these big panoramas, I won’t have the parallax error.

Embrace failure

The most common mistake, in my opinion, is that people tend to underexpose because they are a bit afraid of ISO noise. I would advise going crazy, see what the camera does, see what you like and what you don’t like. Play around with extreme long exposures, get a feel for what you like and what your camera is capable of doing.

That’s a good start, understanding your personal boundaries. Learn from your mistakes. If you’re not happy with a photo, you should analyse why you’re not happy with it and make changes for next time.

The Andromeda Galaxy in a spin. Taken with a Sky-Watcher Esprit 100 ED telescope, ZWO ASI2600MC Pro camera, Sky-Watcher AZ-EQ5 GT Pro mount. There were 15 300-second exposures for a total of 75 minutes. Stacked and processed using PixInsight. © Göran Strand

Beginners’ steps

Perhaps the most surprising thing for beginners is that the cold and the darkness is more intense than they could imagine; they get a bit stunned and can’t do anything, see anything, feel anything. Usually I tell them to learn about their camera like you’re blindfolded, get to know every bit about it in darkness – changing exposure, ISO, manual focus, the basic things so when you’re out in the dark wearing thick clothes you can do all that. If you can’t handle the equipment you get really frustrated, and frustration isn’t good for creativity.

Beware bear

Sweden doesn’t have any wild animals that are dangerous during winter but during March and April you should be a little bit careful because there could be bears waking up from winter sleep who could be a bit hungry. That time of the year I stay close to my car and have a door open with the radio on.

We also spoke with Göran about capturing the Northern Lights here: Capturing the Northern Lights with Göran Strand

Shoot the Northern Lights with Göran on his upcoming photography holiday, Northern Lights in Abisko 10-13 March 2022.

Enter Astronomy Photographer of the Year

Astronomy Photographer of the Year 14 is now open for entries! You have until 12pm (GMT) 4 March 2022 to enter.

Enter here: rmg.co.uk/astrocomp

See more photography competitions to enter here: Best photography competitions to enter in 2022

Related Articles:

Night photography with distinction

Day to Night: how to blend multiple images