Canon’s Utsunomiya factory, where all of its high-end L series lenses are built

Over the past 30 years Canon has produced 90 million EOS cameras and 130 million EF lenses. It’s an astonishing figure which vindicates Canon’s decision back in the 1980s to abandon its popular FD mount in favour of the new electronic EF mount, rendering its then-entire, existing system obsolete at a stroke. Canon’s subsequent conquest and domination of the 35mm SLR market, followed by the DSLR market, is entirely due to that move, because the new mount laid the foundations for all the ground-breaking technology that followed.

To celebrate this milestone, AP was one of just two UK and four German publications invited to visit Canon’s global headquarters in Tokyo and tour its Utsunomiya lens plant, where its L-series lenses are made.

Canon’s Utsunomiya lens factory was built in 2005, and lies around an hour north of Tokyo by bullet train. It’s an imposing grey, low-rise slab of a building, surrounded by manicured lawns and car parks, all of which appear to be unblemished by even a speck of dust. Adjacent to the factory, on the same site, is the lens laboratory, where the research and development into new products takes place. We wouldn’t be visiting there!

A warm welcome

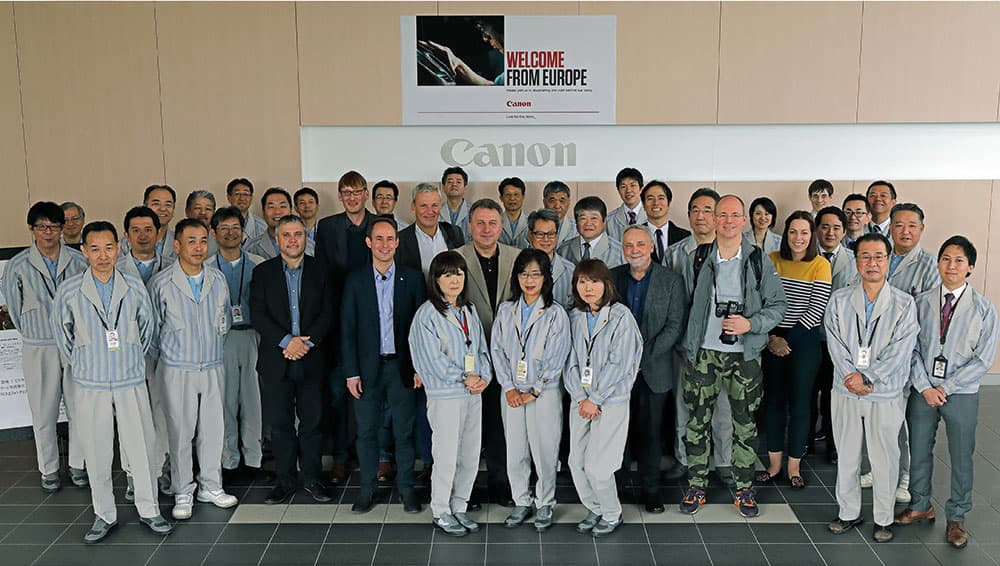

Three flags flew at the factory entrance: those of Japan, Germany and the UK, in our honour. At the entrance the factory’s senior management stood in line to greet us. The Plant Manager, Kenichi Izuki, who is responsible for the smooth running of the factory and its approximately 1,700 employees, led us to the meeting room where we were introduced to the brains behind Canon’s EF lens programme. Finally we donned our stripy jackets and soft shoes and passed through the security doors to where all the magic happens.

The business of designing and manufacturing lenses is an incredibly exacting process. That’s no surprise, but just how exacting is something that you might find difficult to get your head around. Canon’s 4K/8K broadcast lenses, for example, are built to a tolerance of within 30nm, or 30 millionths of a millimetre. To put this into perspective, if you could enlarge a polished lens element to the size of the Maracanã Stadium in Rio de Janeiro, the deviations in surface accuracy would have to be less than the thickness of a plastic bag!

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Every Canon lens starts life not in the factory but in the R&D labs across the road. Indeed before even that happens, there is the market research conducted by the Business Planning Department at Canon’s Tokyo HQ, into what is required by the customer.

Kenichi Izuki, the Plant Manager of Canon’s Utsunomiya factory

The design phase

So where do the ideas for new lenses come from? I posed this question to Canon’s senior lens designers, Manabu Kato, Tetsushi Hibi and Seiichi Kashiwaba.

‘We have an ideal lens, as a vision, for each of the categories that we operate in,’ they explained, through a translator. ‘We also spend a lot of time listening to our customers, and this lets us know what sort of things they are looking for.

At the same time we look at the technology we have in house, and we identify where the gaps are between what we would like to do and what we can do. That is the engine that drives our technological development.’

Once the Business Planning Department are satisfied that there is a market for a lens, and that it’s technically achievable and economically viable, the head of Canon’s lens division, Naoya Kaneda, gives the green light for the concept to go into the product design phase.

Computer software is used in their design process, but rather than work with existing off-the-peg applications, Canon has built its own software. ‘We felt that we could do better using our own in-house expertise,’ says Mr Kaneda, frankly.

Designing a new lens isn’t just about deciding how many elements it will have and what shapes they’ll be, but also the composition of the glass itself. Glass can be made from a variety of metallic oxides and other ingredients. The designers have extensive knowledge of the chemistry and composition of different types of glass and the effect this has on optics. Combining different types of glass elements within a single lens to achieve the desired result is part of the skill of lens design.

According to Kengo Ietsuka, manager of the Business Group, it’s relatively easy to make a high-quality lens if you don’t have to think about the size and weight of the lens, but for Canon the challenge is about achieving a balance of size, weight and quality. But for Shingo Hayakawa, Kaneda’s deputy, the biggest challenge when producing L-series lenses is the extra durability that they require. ‘It’s one of their defining qualities,’ he says.

Since none of the machinery required to make a new lens has been built yet, the early prototypes are made largely by hand.

‘If it includes a new piece of technology that we’re introducing for the first time, such as when we developed the IS system, we’d do a partial creation of the prototype to see how it performs, and fine-tune the specifications accordingly,’ explains the team. ‘If we’re confident about the design and how it will work we will try to create as finished a prototype as possible.’

In these early stages there is constant back and forth communication between the lab and the factory. ‘We work closely with the plant to overcome the challenges that we will face in manufacturing the lens,’ continue the designers. ‘We don’t just give the factory a design and say, “Here, make this.” For example, when we developed the EF85mm f/1.4L IS USM, the biggest challenge was that the IS unit for this lens was very large; so it took longer to create than average.’

Our welcoming party at the Utsunomiya lens factory

The next steps

When a prototype is created it does not go into production straight away. ‘The production timeline for a lens is a matter of years rather than months,’ explains Mr Kaneda. ‘Once we have designed the lens and made the prototype we spend a lot of time testing and listening to feedback from professional photographers. We have testing areas where minute adjustments are made to the optics, and we also have an area where we hit the lenses and drop them on the ground to ensure that the final products have the highest standards of durability. For example, if you compare the Mark I of the EF24-70mm f/2.8L USM lens with the Mark II version, you will see that the durability has been greatly increased.’

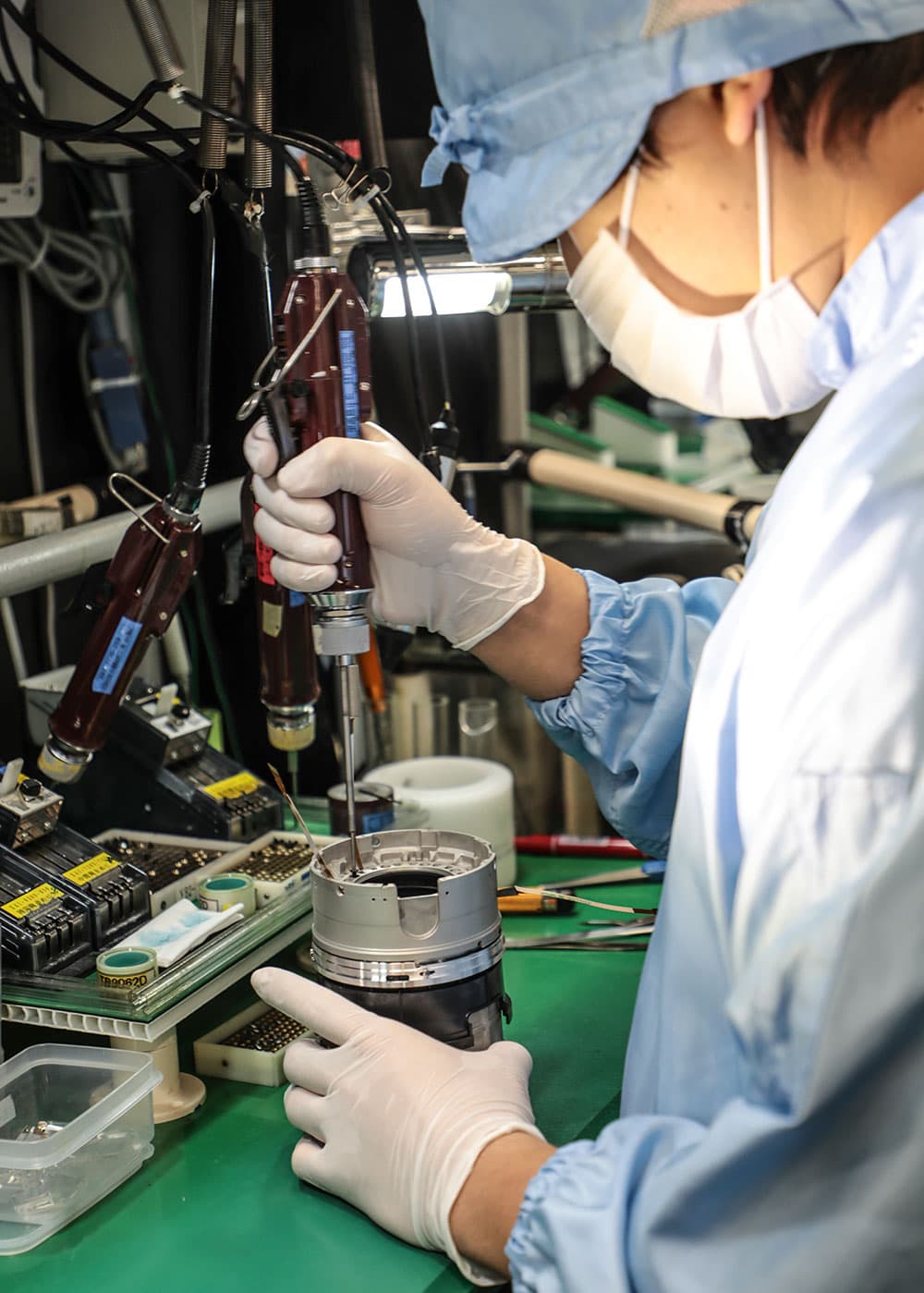

Before a new lens goes into production, the machinery to make it first has to be built, and here Canon also has its own in- house team – the Production Engineering department. According to Plant Manager Mr Izuki the biggest technical challenge for the manufacturing team is achieving consistency. ‘All the lenses that come off the line will be within a specified level of tolerance, but making each one as close to identical as possible is very difficult. We strive to achieve as little variation between lenses as possible, so we do a lot of fine-tuning on the production line.’ Canon has around 90 lenses in its current range, and it would be impractical to be making all of them all of the time, so Mr Izuki is given a production schedule which specifies how many of which lenses need to be made over the next month. ‘There are some lenses, such as the TS-E tilt/shift ones, where there is a team working on a special line spending two hours a day making these. But this is the exception,’ he says. ‘Mostly we have parallel lines running continuously all the time.’

Making the lenses

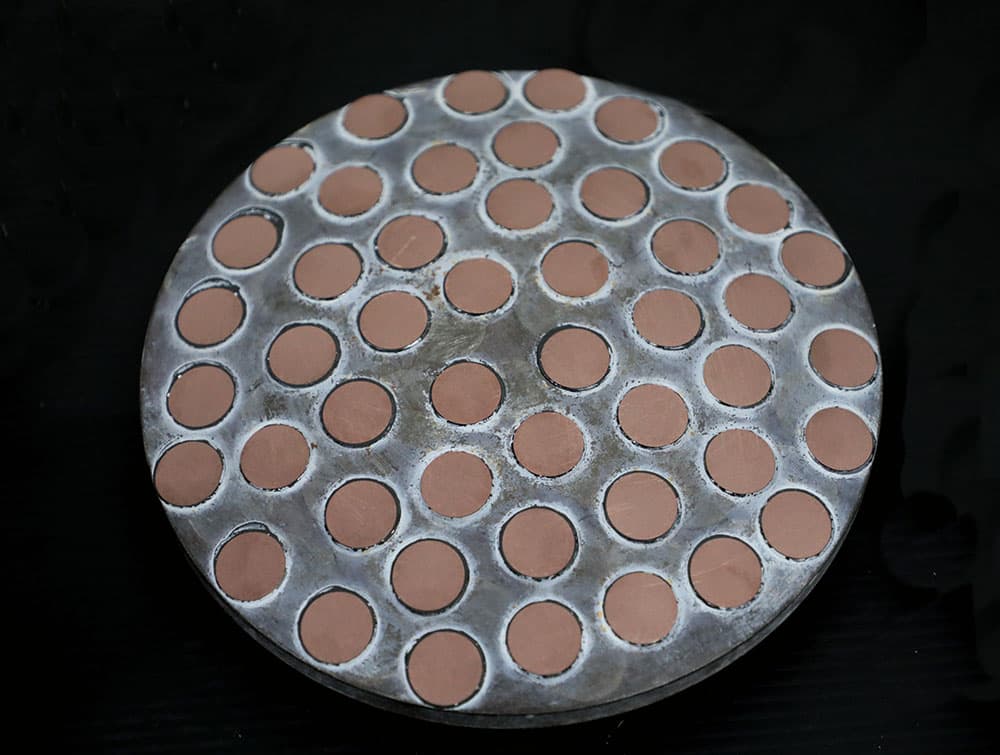

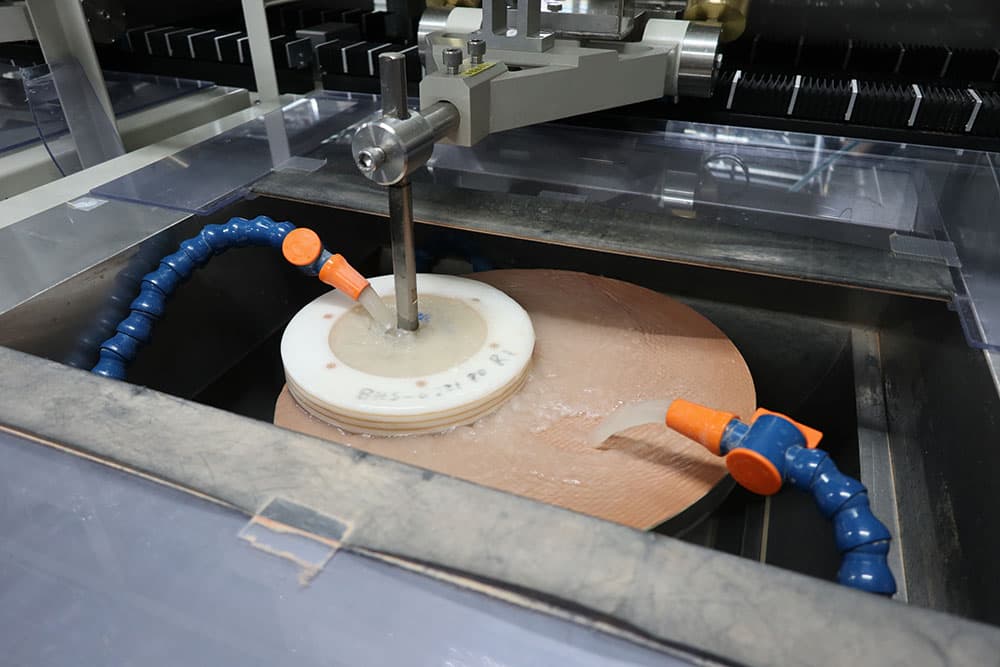

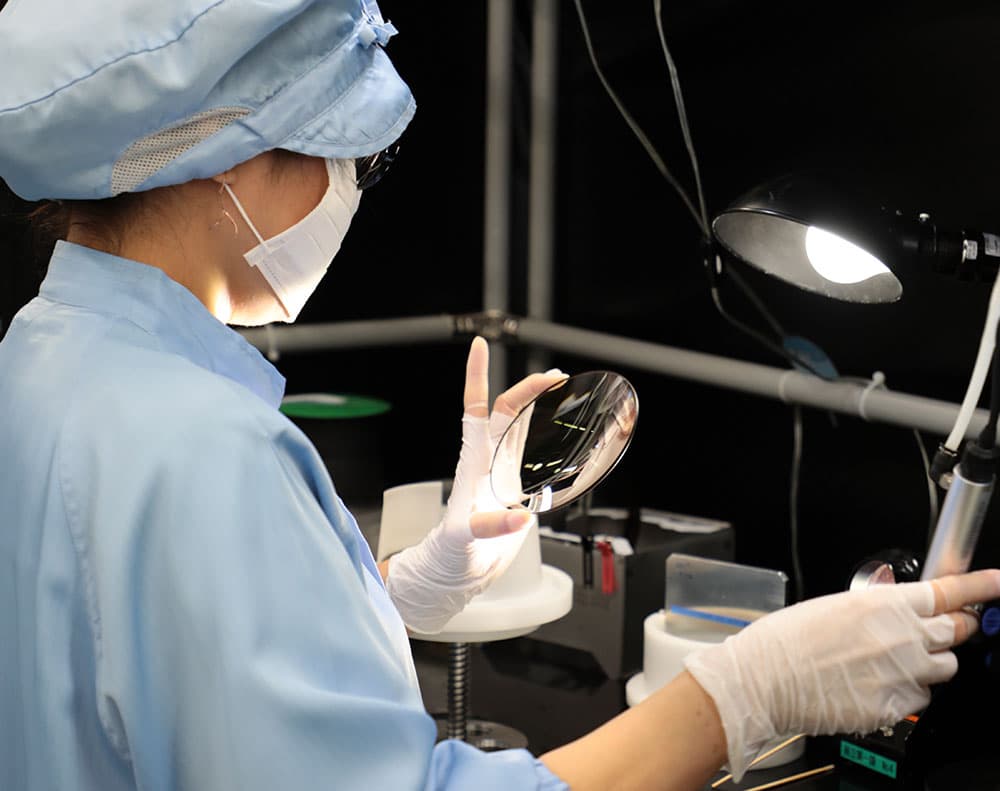

There are five stages to turning a lump of glass into a Canon lens. Stage 1, Rough grinding: this turns the lens from a rough tablet of frosty glass, called a ‘cake’, into a curved surface of a specified dimension. Stage 2, Smoothing: where the lens is fine ground to the proper degree of roughness and surface curve, using a curved drum embedded with diamond pellets. Stage 3, Centering: at this stage the optical axis of the lens is adjusted, by fine-tuning the curvature of the lens. Stage 4, Polishing: here the surface of the lens is polished using a rotating polyurethane pad until the lens becomes transparent. Stage 5, Inspection: the lens is tested and inspected to ensure it meets the required standard.

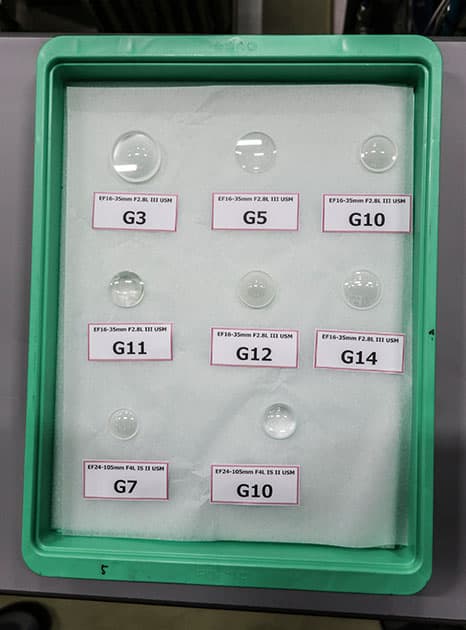

With most of the smaller, non-aspherical lenses, this process is now automated using a machine designed and built by Canon’s Production Engineering division. This machine cleverly measures every lens that goes down the line and applies optical corrections as it goes. During our visit we watched a machine that produces elements for the EF16-35mm f/2.8L III USM in around 30 minutes.

But the more specialised lenses, like the super-telephotos and the 4K/8K broadcast lenses, are still made largely by hand by craftsmen with decades of experience. Craftsmen like Toshio Saito, who has gone beyond the title of ‘meister’ to that of ‘Takumi’, or master craftsman, for his 30 plus years of lens polishing experience, and now heads that department. Indeed, most senior staff seem to have spent their working lives at Canon, which perhaps explains the palpable sense of loyalty and pride in everyone we met.

Canon’s obsession with perfection and fine detail was brought home to me when I happened to glance at one of the six framed prints on the wall of our meeting room and recognised Brighton’s West Pier. ‘That’s a coincidence, I live in Brighton,’ I said, before realising that it wasn’t a coincidence at all. Six guests, six prints, each one representing one of our home towns. At that moment it became clear why Canon has managed to achieve such a global domination of the camera and lens market for so long.

[breakout]

Making the lenses – step by step

1. Small autonomous robots are programmed to tow the cages of components to various parts of the factory, following lines on the floor

2. A lens element in its raw state, known as a ‘cake’

3. A diamond plate, covered with diamond discs, for the grinding, shaping and smoothing of elements

4. Toshio Saito, the lens polishing ‘Takumi’ who has been polishing lenses for Canon since 1981

5. It requires over 20 years of experience to master the art of lens grinding and polishing

6. An element is smoothed, before being centred and polished. The water is purified and recycled

7. The assembly line where smaller, non-asperical lens elements are automatically ground, shaped, centred and polished

8. An automated lens assembly machine

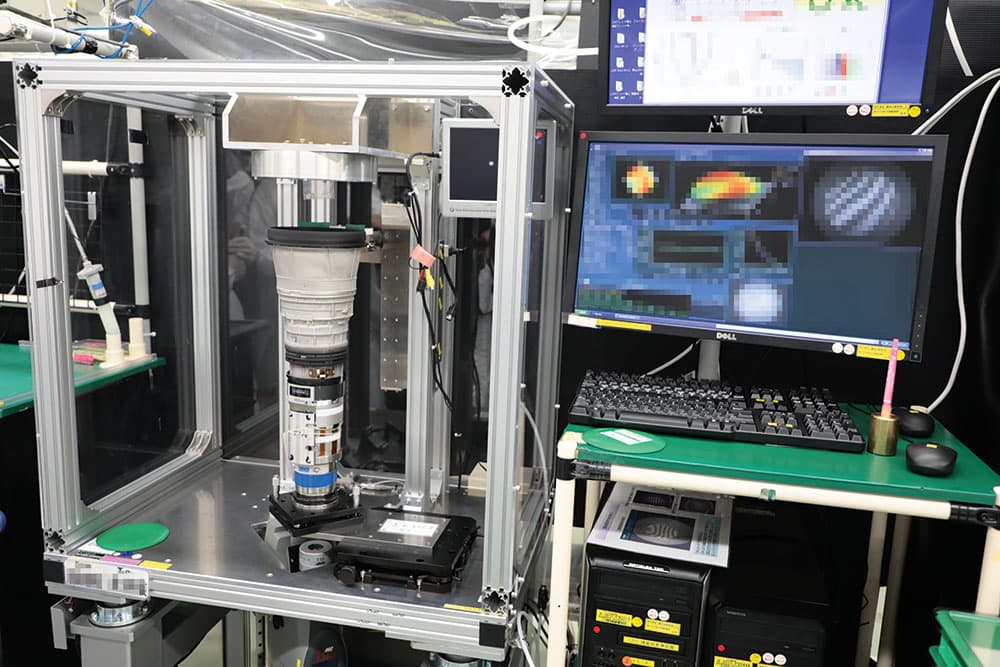

9. An EF600mm f/4L IS II USM lens is checked by computer to ensure it is within performance tolerances before the outer casing is added

10. A worker assembling one of Canon’s £11,000 EF600mm f/4L IS II USM telephoto lenses by hand

11. The front element for an EF600mm f/4L IS II USM lens is checked before being fitted into the lens

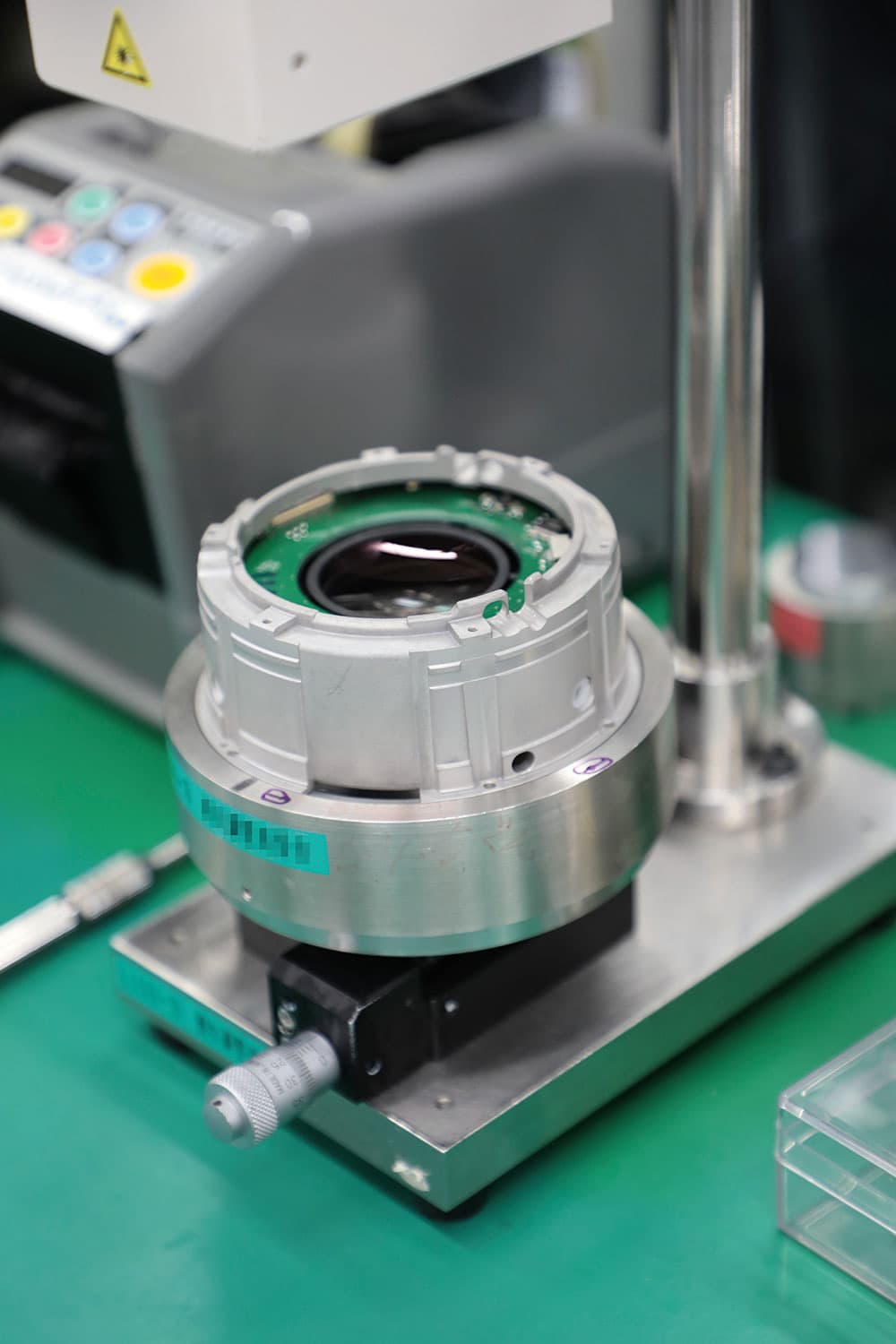

12. Canon’s ground-breaking image stabilisation unit

13. Attaching the Image Stabilisation Unit to a lens

14. Canon’s aspherical lenses are made here using a special glass moulding, or ‘GMo’, process

15. The lens inspection area where finished lenses are quality tested using Canon’s own charts

[/breakout]

Interview with a Takumi

Five minutes with Toshio Saito, Canon’s master lens craftsman

Mr Saito joined Canon in 1981 as an apprentice and did various jobs before finding his niche as a lens polisher. As the Takumi, he oversees all lens polishing at the plant (they polish approximately 5,000 lens elements per day at Utsunomiya) and is also responsible for training the next generation of lens polishers.

What are the most difficult parts of the job to master when learning to be a lens polisher?

The greatest challenge is the level of precision required – achieving that one to the millionth. Building the experience to know by eye what is required takes a long time. Lens polishing is one of the most difficult parts of the lens-making process, and you have to develop and use the three senses: sight, hearing and touch. Hearing, because when the lens touches the diamond plate it makes a certain sound, and you get to know when that sound isn’t right. Also, with touch, you pick up the vibrations in your hand and you can tell by the vibration when something isn’t right.

What makes a good lens polisher?

They have to be able to work to the precision required, but also when a lens fails to achieve the required standard, they need to be able to identify the best way to correct it. They need to look at the lens and say, ‘Okay, this is what I need to do’ and go straight to the solution, rather than taking the long way around.

What qualities make a good Takumi?

You just have to like lens polishing. I am the Takumi, but I don’t actually know what I’m good at. But people tell me that I’m good so I just keep doing it. But I can probably say that I work with speed. When it comes to completing a lens to perfect condition I work much faster than other people, so that tells me that I am at a higher level.

Do you oversee all the lenses made in the Utsunomiya factory?

I oversee the polishing of all the lenses that Canon produces here. But with the higher-resolution broadcast lenses, where it is more difficult to achieve the required level of precision, I get hands on and do them myself.

Which are the most difficult lenses to polish?

The super-telephoto lenses, with their large front elements, are very difficult, and also lenses that have a high curvature, such as the wideangles.

[breakout]

Aspherical lenses

Aspherical lenses use complex shapes to suppress various aberrations. Generally designed using a computer, these elements can’t be produced using the same rotating machinery as the regular elements. Canon uses three methods to produce aspherical lenses, depending on the characteristics required. The first is by grinding the lens in the conventional way. This is time consuming and requires very precise control of the machine, but it is still the method required for larger elements. The second is by fixing ‘bumps’ of glass onto a regular element; and the third is by Glass Moulding. GMo Aspherical lenses are lenses that have been heated, shaped in a mould and then cooled. This method is the most sophisticated and has to take into account changes to the lens’s shape and characteristics as it cools. Unlike many lens manufacturers Canon produces its own GMo aspherical lens elements in house, using its own machines.[/breakout]