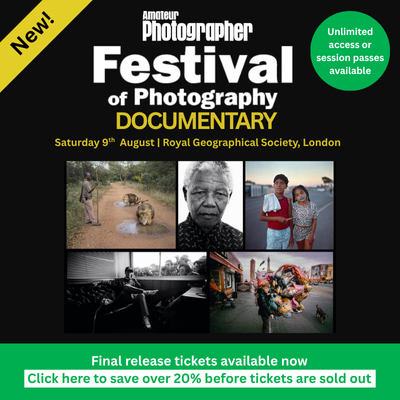

Nikon Df: At a glance

- 16.2MP million-pixel CMOS sensor

- Single-lens-reflex viewfinder, 100% coverage

- 3.2in LCD, 921,000-dot fixed LCD

- No video mode, despite live view option

- 765g with battery and memory card

- 143.5x110x66.5mm

Imagine rediscovering photography. Imagine that everything (well, a lot of things, anyway) could be as fresh as when you first started to take photography seriously, even though you now know a lot more. To a considerable extent, that’s what the improbable combination of a Nikon Df and a manual-focus 55mm f/2.8 Micro-Nikkor lens has done for me.

It was (and is) up against stiff competition. I’ve been using M-series Leicas for more than 40 years, and I have Leica-fit lenses from 15mm to 135mm. Since about 1980, a 35mm f/1.4 Leitz Summilux has been my ‘standard’ lens, increasingly supplemented of late by a 50mm f/1.5 Zeiss C-Sonnar. I still use my M9 a lot, because it suits much of what I like to do, and it’s great for wideangles and fast lenses. The Df is, however, better for precise framing, closer focusing and long lenses. Battery life is far longer, too.

As so often, chance played a large part in how and why I bought it. By about 2005, I could no longer afford to use film exclusively: editors just weren’t interested in enough film-based articles. Also, digital is quicker, cheaper and better than Polaroids for quick ’n’ dirty illustrations such as pack shots and step-by-steps. If I’d been purely an amateur, I might never have embraced digital at all.

Meanwhile, since about 1990, film SLRs had been growing ever bigger, fatter and more complicated. Professional-quality DSLRs, by the time I was ready to consider them, were ridiculously big, heavy, clumsy, ugly and expensive. A digital Leica M-series was (and is) less expensive than a top-of-the-line DSLR. I couldn’t afford both, and I was a lot happier with an M8. For hackwork, a Nikon D70 did all I needed.

Then, in 2014, it died. I decided to go for full frame, either a Nikon D800 or a Df; I’d been using Nikon Fs since the mid-1970s, and had numerous manual-focus lenses. American Photo magazine wanted a review of the Df, which would make a nice dent in the price, and I ended up buying one from Grays of Westminster. I haven’t regretted it for one moment.

Church of St Martin, Noize. No tripod? No problem at ISO 12,800

Initially, I thought it would be like an improved version of the strictly utilitarian D70. There was no way (I thought) that I’d be using it instead of the Leica for personal photography.

I was wrong. Even before I got the Micro-Nikkor lens, I sometimes used it for shooting vide-greniers (a bit like car boot sales but a lot more interesting) and a few other things, too. As my wife Frances Schultz said, ‘It must be a good camera, because it’s the only digital camera you’ve ever used that you haven’t wanted to throw across the room within a few hours of getting it.’ Even so,

I doubt it ate into my Leica usage by even 10%.

Then, two years after buying the camera, I bought a second-hand Micro-Nikkor lens for £120 from Ffordes. Only later did I discover that it’s still available new: Grays lists it at £541. I bought it because although my Kaiser copying stand is a brilliant piece of kit, my other macro lenses are inconveniently long. Inevitably I tried the new (old) lens for other things as well, just to see what it was like. I loved it. Why?

Close focusing

The initial reason why I liked it was the close focusing. Although I can shoot close-ups with the Leicas, it’s not always easy: I usually need to change lenses. Sure, I can get closer with the AF-S 50m f/1.8G I was forced to buy with the Df (at the time it was available only as a with-lens kit), but I still can’t get really close. The Micro-Nikkor focuses down to half life size. I’ll come back to its other advantages in a moment, but before that, it’s worth looking at the other half of the combination: the camera.

The Df is probably the nearest you can buy to a traditional film SLR. It’s relatively small and light, while still retaining the heft of a real camera at 765g – about 10% heavier than a plain-prism F. The pentaprism viewfinder shows 100% of the image. It takes a cable release instead of an electronic gewgaw. Shutter speeds are set on a proper dial. So are ISO speeds, up to insanely high levels: even ISO 12,800 still delivers astonishingly good quality, a function of having only 16.2 million pixels on the same full-frame sensor as the vastly more expensive D4. This is where things get interesting, especially when combined with the Micro-Nikkor.

This is the sort of picture I shot for years with Leicas. The Nikon is just as suitable. 1/60sec at f/11, ISO 400

Many years ago, I had a 55mm f/3.5 Micro-Nikkor. With ISO 400 film it was inconveniently slow: this was long before the days of Ilford Delta 3200. The Df, though, offers excellent quality at high ISO speeds: ISO 400 at f/1.4 demands the same shutter speeds as ISO 1600 at f/2.8. At ISO 1600, the Df is incredible. The highest speed, H4, offers over ISO 200,000 equivalent, but quality is awful: it is essentially a surveillance setting.

High-quality ISO speeds up to 12,800 was the second reason I fell in love with this combination. Not only can I take handheld shots in very poor light, but in good light I can shoot extreme close-ups at f/32 (for depth of field) and with short shutter speeds (to avoid camera shake). I’m only just beginning to explore this. There’s some image degradation due to diffraction and noise, but it gives me whole new realms of picture taking. Besides, the degradation hardly shows in small images or on a computer monitor. As for the f/2.8 maximum aperture, I’ve never cared for shallow depth of field just for the sake of it: f/2.8 is usually plenty for differential focus. Alternatively, I can change lenses or switch to my Leicas.

Although 16MP is quite modest by modern standards, it’s around the point at which you need to start using a tripod if you want to see any significant improvement in resolution: handholding rarely delivers all the resolution of which a lens is capable. Another advantage of ‘only’ 16MP is file size: images from the D800 (since replaced by the D810) take longer to load and process, and you need more storage space.

White balance is via a button on the back that opens a menu, so the main reasons for diving into other menus are formatting the memory cards, and setting up old lenses so that the meter works.

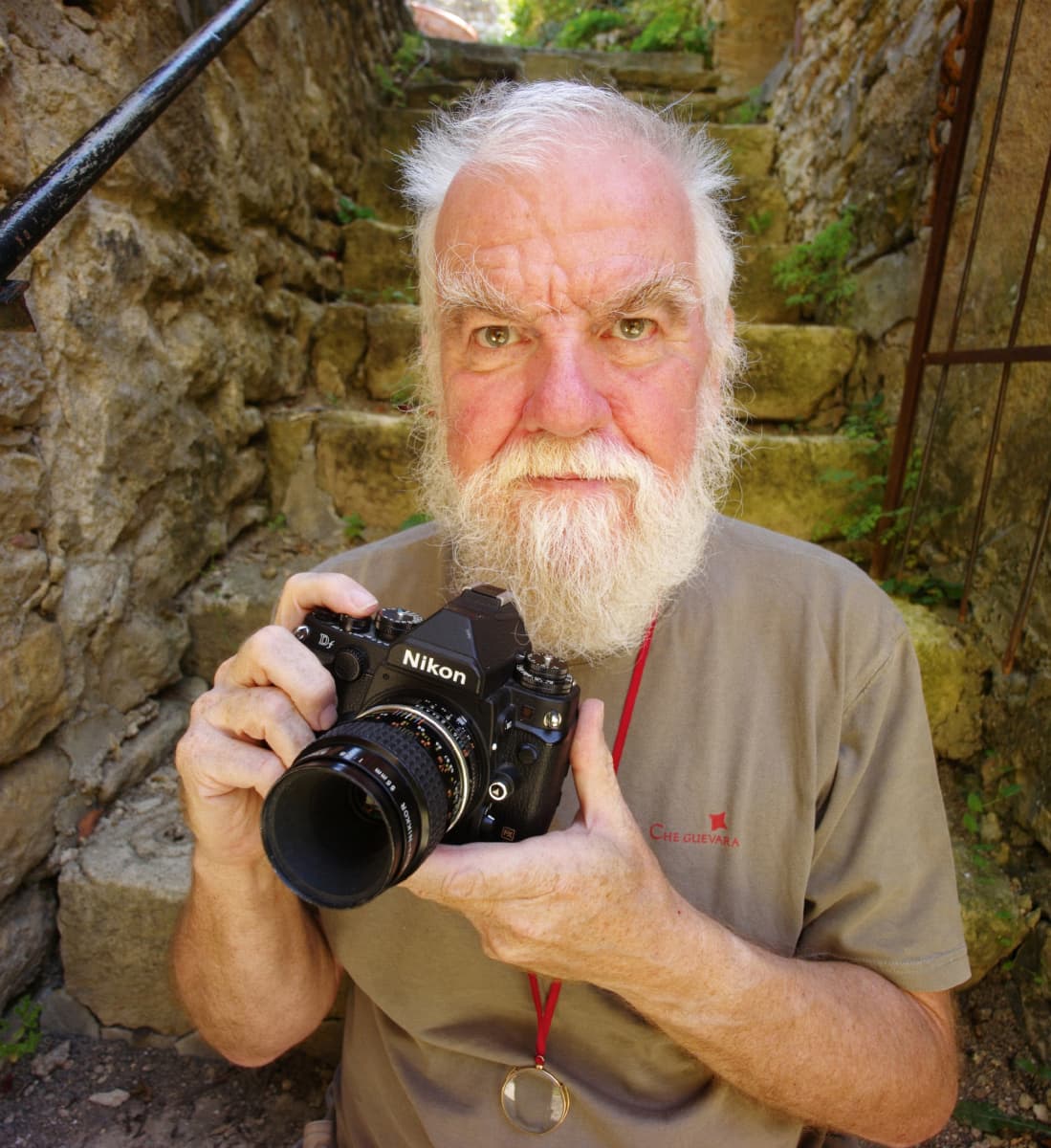

The Df can accommodate up to nine manual-focus AI lenses at a time. For each lens, once only, you enter focal length and maximum aperture. It doesn’t take long. I use the nearest Nikon equivalent for non-Nikkors, such as 200mm f/2.8 for my 200mm f/3 Vivitar Series 1. Thereafter, it’s three menu steps (Setup; Non CPU lens data; Select lens) whenever you change lenses. This is a slight hassle, but as it enables me to use my old Nikon-fit lenses I’m not complaining. I’ve used lenses from 14mm up (Sigma 14mm f/3.5 rectilinear, which vignettes badly on digital until about f/11) but all the illustrations here, except the picture of me with the camera, were shot with the Micro-Nikkor. Here’s why.

Too many people at a classic car show? Shoot medium shots and close-ups instead. 1/125sec at f/5.6, ISO 400

First, as already mentioned, it focuses very close indeed. It lives on the camera. Even if I don’t need to focus close for one picture, I can for the next.

Second, I find manual focus far quicker and more reliable than autofocus, where the choice is between blind faith, moving the autofocus point and focus locking. Blind faith is useless when the autofocus spot is not on your principal subject. Moving autofocus points is impossibly slow and tedious, although easy to do accidentally. Focus/exposure locking is not too bad if you use the dedicated lock button, but I find it no quicker or easier than manual focus.

Easier to visualise

Third, it’s a prime lens. This makes it much easier, at least for me, to visualise exactly what I want in the viewfinder and to stand in the right place at the right time. Yes, I understand the theory of using a zoom as a bag of primes, setting, for example, a 24-85mm as if it were a 24mm, a 35mm, a 50mm and an 85mm, but I can’t bring myself to work in that way. I waste time tweaking the focal length. As a result, I often miss pictures.

Fourth, there’s a manual diaphragm ring marked with apertures, not an unmarked dial on the camera body with a readout only in the viewfinder.

Fifth, it has a meaningful depth of field scale. This provides only a rough guideline, but autofocus lenses don’t offer even that. There’s an IR focusing mark, too.

Sixth, it accepts all the 52mm Nikon filters I have collected over 40-plus years.

Seventh, despite a 2/3-stop increase in speed, the image quality is even higher than the old 55mm f/3.5, thanks to a six-glass, five-group reformulation. Excellent flare resistance is further aided by the deeply recessed front element.

Mill stream. The DF is the sort of camera that makes you go out looking for pictures, and manual focus beats autofocus for reflections in rippling water. 1/125sec at f/8, ISO 400

Of course, neither the camera nor the lens is perfect. I have already mentioned the wandering focus point. I wish there were a way of locking it in the middle and leaving it there. Some other buttons are too easily operated, too. For example, a few weeks after buying it, I panicked after I’d put the camera in a pocket and inadvertently turned off the autofocus. There are at least three more buttons I have never used or needed, and the day I bought the camera, I disabled the sub-command dial. I’ve yet to miss it – I wish I could disable more. As with any digital camera, some menus are about as far from intuitive as they could be, at least for me.

The viewfinder screen is not optimised for manual focus, but it works pretty well: in-focus images are significantly contrastier than out-of-focus. Also, the focus confirmation spot is astonishingly effective, even in light that is too poor to allow easy visual focusing.

Micro-Nikkor 55mm f/2.8 lens

Moving on to the lens, the focusing ring has an understandably long focus travel of about 300°. This doesn’t worry me: it focuses down to half life size, after all. It is, however, easily nudged, especially when I remove the camera from my eye. I miss focus sometimes, but less often than I did with the autofocus 50mm f/1.8. Enough technical flim-flam, though. What do I actually shoot with it, and why?

Well, I’ve had the Micro-Nikkor lens only for a couple of months, but you can see more examples on my website at www.rogerandrances.com. Things like ‘The Secret Life of Chairs’ or ‘Recycled Religion’ could equally well be shot with either. So could the series I’ve just started, ‘Beach Towels’.

The Df is good for street photography, too. This camera is not ageing elegantly, so it looks a bit battered, and the M9 is well brassed. Many tend to mistake both for film cameras: the preserve of bumbling old eccentrics (and, one might hope, wide-eyed young art students) rather than predatory paparazzi. Retro-looking cameras with physically smaller lenses tend to be regarded as less ‘threatening’ than massive DSLRs with big zooms. It’s a bit like steam engines or vintage cars: people are always more comfortable with things that seem familiar, even if (like steam engines, vintage cars and manual-focus cameras) they are not actually very common any more.

Micro-Nikkor 55mm f/2.8

I do a lot more close-ups with the Df, simply because I can, and then there are the low-light and small-aperture shots. And, of course, I use it for the purpose for which I originally bought both the camera and the lens: illustrations, close-ups and copying. There’s even a piece on my website based on copying: mostly, a selection of photography ads from a 1909 edition of Simplicissimus magazine.

The bottom line is this: it is never going to be easy to get every picture you can imagine, exactly the way you want it, with any camera, be it manual, automatic or hybrid. There are always going to be times when you have to substitute experience and intelligence for automation. If I rely on automation, I quickly get lazy. Sooner or later that trips me up. With an all-manual camera, I have to pay attention all the time: not very much, but enough to keep me thinking about what I am doing. This is always a good idea.

The Nikon Df will not suit everyone. The same is still truer of the Micro-Nikkor lens. But I’m not ‘everyone’. I’m me, and the combination of the Df and the Micro-Nikkor suits me better than I would ever have thought possible. It has given SLR photography back to me. Ask yourself if you, too, differ from ‘everyone’. If you do, look at the Nikon Df. And maybe at the Micro-Nikkor as well.

Points of interest

Much of the charm of the Df/Micro-Nikkor combination lies in what isn’t there.

Roger Hicks with the Nikon Df and Micro-Nikkor 55mm f/2.8 lens

Manual shutter-speed dial

You can set the shutter speed with the camera away from your eye. This is often useful when you want to work quickly and unobtrusively, especially in street photography, or when the camera is on a copy stand.

ISO dial

There’s no need to go wading through menus. I normally leave it on ISO 400, because that’s the most familiar speed for me, but I use higher speeds, up to 12,800, in poor light.

Manual focus

As noted already, I find manual focus quicker and more reliable than automation or using AE/AF lock.

Manual aperture ring

As with the shutter-speed dial, it is often useful to be able to set the aperture without having your eye to the viewfinder.

Colour-coded depth of field scale for f/11, f/22, f/32

This is only a rough guide, but a lot better than you get with AF lenses.

WB button

All right, it takes you to a menu on the back of the camera, but so long as you hold the button down, the thumb wheel lets you flick from one setting to another. Custom WB, pre-sets and colour temperature settings are only slightly more difficult.