My first photography project came about rather unexpectedly. Photography projects had always been something I’d liked the idea of doing, but had never quite got round to starting. Instead, my photography just seems to have evolved into one big, sprawling, open-ended ‘East Anglian landscape’ project with no real plan to speak of and no end in sight. Then, in the summer of 2014, I received an email from the National Trust asking if I’d be interested in taking on a year-long project to capture images of the East Anglian coast. And, just like that, it seems I’d found myself a project.

Orford Ness and its fascinating history creates a mix of man-made relics in a wild landscape

Diverse landscape

For those of you unfamiliar with this part of the world, the East Anglian coast is diverse and, for want of a better word, ‘quirky’. It’s not the sort of rugged, rocky coastline that usually draws photographers, but no less interesting.

In the muddy Essex estuaries of the south of the region lurk remote islands of saltmarsh. Once the site of battles with invading Viking hordes, they are now teeming with birdlife. Moving north, Suffolk’s ‘sunrise coast’ boasts Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty and Sites of Special Scientific Interest – everything from marshland and shifting shingle spits to remote beaches fringed by dunes and crumbling sandstone cliffs, topped with heather and gorse.

Finally, the Norfolk coast has wide, sandy beaches and dunes, saltmarshes with creeks running like capillaries through them, quaint harbours where boats sit scattered in the mud at low tide and undulating cliffs – all this under those endless ‘big skies’.

Norfolk’s Brancaster beach at low tide – a broad stretch of sand fringed by dunes

The brief for this project was to capture specific locations along this coast and how they change with the seasons – everything from classic views to unusual details, summer wildflowers to wintry storms – all in my own style.

Getting started

I always found that the biggest obstacle to starting a project was deciding on the idea and scope of the project itself. I didn’t have that problem now, but I did have a dozen or so places on my list, and if I was going to be in the right place at the right time to capture all the images I needed, some serious planning would be required.

My first thought was to come up with a comprehensive shot list to work through, but I was concerned I might end up going through the motions, moving from shot to shot without any emotional response to what I was seeing.

The coastal cliffs of Sheringham make a subtle background for clover flowers

Instead, I aimed to come up with at least one ‘iconic’ view for each location – a single image that captured the spirit of the place. This would be the starting point from where I could look deeper and build a collection of images. I hoped to get the classic views out of my system at the very start, then with some shots in the bag and a few ideas in my head I could relax, go with the flow and see where it took me.

The planning began with internet research on each location to find what was unique or special about it, where the iconic views would be and what else was there to shoot. Would there be wildflowers and, if so, when would they be at their peak? Would it be best at low tide or high tide? Once I had an idea of the important images I wanted for each place, I used www.suncalc.net (a website that shows the angle of the sun throughout the year) to work out at what time of day and year the light would be best to capture them.

Make use of websites to work out the angle of the sun at any time at any given location

There are a host of useful websites for researching everything from tides and sun positions to finding footpaths and places to park, but while the internet makes researching projects like this a lot easier, it can only tell you so much. There’s no substitute for taking a map and seeing the lie of the land for yourself and, ultimately, my first trips of the project were as much to explore the location as they were about photography.

Building a schedule

As the plan for this project developed, I made notes in a diary and began to build up a schedule for the year ahead. This might sound a little over the top but, aside from my appalling memory, I had to arrange access in advance to certain sites.

One of the perks of working on this project was that I had access to some of the harder-to-reach coastal sites at unusual hours, so I could get the shots I wanted in the best light. To shoot star trails, I was able to stay overnight at Orford Ness, a shingle spit on the Suffolk coast, which is usually only accessible by boat during daylight hours. Blakeney Point on the north Norfolk coast, where I had the privilege of accompanying the rangers as they counted the pups in the seal colony, is equally difficult to reach. These visits all needed to be arranged in advance, so it was important to plan ahead.

Overcoming problems

With such a detailed plan, all that was left to do was turn up with the camera and take the photos, right? Not quite. I came up against some interesting problems and it often took several visits to get the images I wanted.

The weather always made life difficult. The mild winter weather was disappointing and the dreaded coverage of blank white cloud was a frequent nuisance. I always find going with the flow is the way to deal with the weather. There’s almost always something to be salvaged from any conditions. For example, the even lighting on blank-sky days is ideal for detail shots.

I knew I’d have to deal with the weather, but I hadn’t envisaged some of the more unusual issues, like missing the dawn light because I was trying to dig out a vehicle that was stuck in the shingle or having to take cover from marauding gulls that were nesting on a building I was trying to shoot.

Surprisingly, though, one of the biggest issues I faced was in my head. I wanted the end result of this project to be a set of images that were in my usual style, but I found that harder than expected. First, it was difficult to ignore what the images were for – I found myself imagining what the end user would think rather than just taking the photo I wanted. Second, I had to change my usual approach for a more disciplined one – most of the images I wanted to capture were time-sensitive, so I had to shoot what was needed.

Positive feedback

Despite these issues, the fact I was doing this project for a client was enough to keep me motivated. I supplied the images in batches throughout the year so they could be used straight away, and the positive feedback I received, as well as seeing my work published, didn’t hurt morale either.

The project came to an end in the autumn of 2015. The images were to be used predominantly for promoting the Neptune Coastline Campaign on everything from the National Trust’s social media and website, to newsletters and press releases. They also found their way onto gifts, from jam jars to jigsaw puzzles. At the end of all the hard work it’s satisfying not only to look back on the collection of photos, but also to see them used in so many ways.

Neptune

In 1965, the National Trust launched Enterprise Neptune (since renamed the Neptune Coastline Campaign), an ongoing fundraising campaign that responded to the need to protect our beautiful coastline from the threat of development. The funds raised were used to buy coastal sites of outstanding beauty and protect them from development.

Nearly 50 years since its inception, the campaign has raised more than £65 million and secured 742 miles of coastline across England, Wales and Northern Ireland. Coast acquired through the Neptune Coastline Campaign has been conserved in as natural a state as possible and managed in a way that enables people to enjoy and use it while encouraging nature to thrive.

Top 5 locations

Dunwich Heath

Home to a variety of wildlife, Dunwich Heath is a large area of Suffolk heathland reaching all the way to the top of the sandstone cliffs that overlook the crashing North Sea. When the heather is in bloom, the sea of pink and purple heather is a stunning sight.

Orford Ness

This is a unique and unusual place that provides a great deal of inspiration for photographers. It has big skies, unusual derelict military buildings set in an exposed shingle landscape, as well as marshland that is home to an abundance of wildlife.

Stiffkey saltmarshes

This is an endless expanse of Norfolk saltmarsh criss-crossed by footpaths and narrow wooden bridges spanning the twisting creeks. In summer the marsh is a haze of gorgeous purple sea-lavender and it’s the perfect place to make the most of dramatic skies in winter.

Brancaster

At low tide, Brancaster beach in Norfolk is a vast stretch of pristine sand, fringed by dunes high enough to offer views along the coast. It’s often exposed and windy, but that wind rearranges the sand beneath the dunes into waves of photogenic ripples.

Blakeney

Blakeney has it all – from the pretty quayside with boats bobbing in the tidal creeks (or wrecked on the saltmarsh) to the wildlife. In winter the freshwater marshes are home to thousands of geese, and Blakeney Point has the largest colony of grey seals in the UK.

Change it up

Lens choice makes a big difference to the image, and making the most of the characteristics of different focal lengths is a great way to help produce a varied collection of images. I like to start with wide shots, then work my way in closer to the details. This project often involved a lot of walking, so to keep kit to a minimum I generally only carried three zoom lenses, which covered all eventualities.

Canon EF 16-35mm f/4L IS USM

Wideangle lenses are ideal for emphasising interesting foregrounds and capturing the wider views.

Canon EF 24-105mm f/4L IS USM

This standard zoom lens was probably my most used for this project. I love using wide angles, but the downside is that distant objects become very small. A standard zoom helps to keep everything in the picture more evenly balanced.\

Canon EF 100-400mm f/4.5-5.6L IS USM

This was very useful for photographing the seals on Blakeney Point, but as well as the obvious uses for wildlife, it’s great for picking out details in the landscape or compressing distance to give a different look to a familiar view.

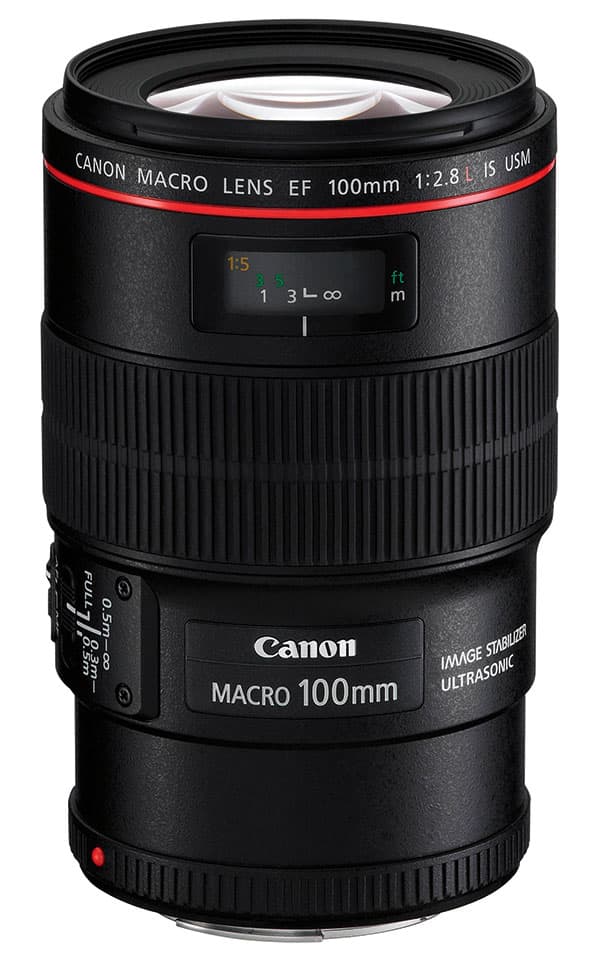

Canon EF 100mm f/2.8L Macro IS USM

This is the least-used lens on this project, but nevertheless still very handy to have in the bag for shooting things like wildflowers.