We can spend hours poring over advice on how best to use our cameras and lenses, but we often overlook how to make the best use of the other accessories we have in the camera kit that we lug around with us.

Admittedly, compared to the plethora of settings on a camera, accessories can seem a little basic by comparison, but this doesn’t mean you should get sloppy with your technique. Even the simplest of accessories have a right and wrong way of being used, while little tricks and techniques can make life not only that bit easier, but can also help you to achieve better shots. Therefore, knowing how to use your accessories correctly is just as important as knowing how to use your camera and lenses.

We take a look at how you can maximise your skills with a range of popular accessories, so you too can get the most from them.

Filters

Filters are a vital accessory, but use them incorrectly and it can be very hard or even impossible to correct the mistakes in Photoshop. Here are a few key things you need to know.

Position your ND grad

Positioning your ND grad correctly is essential for achieving a pleasing shot. Image by Jeremy Walker

When positioning your ND grad, especially when presented with a straight horizon, it can be easy to become complacent. We’ve all been guilty of simply pulling the grad down to roughly the point where the horizon meets the sky and then shooting away. This, though, can lead to far too dark a horizon, so be sure to really study the scene and pay particular attention to positioning the grad line correctly and carefully.

Should a feature – such as rocks or a cliff – protrude into the horizon line, you might want to set the grad at an angle, so these features aren’t too dark in the final image.

Know your density

A 0.9ND filter is more suitable here (left image), than a 0.3ND option (right), which is not as strong. Images by Jeremy Walker

The darkest part of an ND grad varies in exposure value (EV) between filters. One with a lighter density might cut out only 1EV of light, whereas the darkest density grads can cut out as many as 4EVs of light. You don’t want to use a grad that’s too strong for the scene, which might result in the sky appearing darker than you’d like.

Selecting the correct filter can be confusing, as manufacturers give them different names. For example, an ND4 is the same density as a 0.6ND – both reduce the exposure by 2 stops.

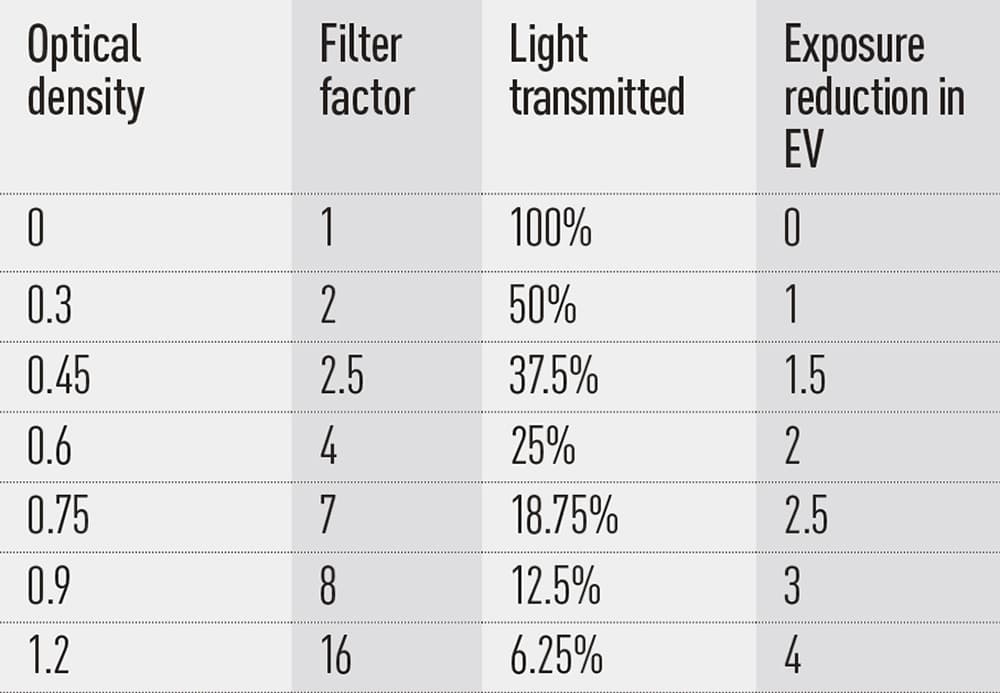

The table outlines the relationship between the optical density, filter factor and number of EVs by which the dark part of the filter reduces the exposure. A good starting point is an ND4 or 0.6ND, which is suitable for the majority of scenes, but this varies depending on the strength of the light.

The table outlines the relationship between the optical density, filter factor and number of EVs by which the dark part of the filter reduces the exposure. A good starting point is an ND4 or 0.6ND, which is suitable for the majority of scenes, but this varies depending on the strength of the light.

Hard or soft?

The unfiltered shot here doesn’t lend itself to a hard grad (left image). Instead, a soft grad delivers a smoother transition (right). Images by Jeremy Walker

After determining the density of filter required, the next decision is whether to use a hard or soft grad. Hard grads have a sharp transition from clear to dark, and are the most popular choice, as they allow the point of transition to be set on the horizon, where the sky is often at its brightest. Soft grads have a much more gradual change from clear to dark, and are suitable for landscapes where there are trees, mountains or buildings above the horizon. The use of a hard grad in these situations would produce a distinct line across these elements in the image and ruin the shot.

Tripods

Always leave the thinnest leg sections until last. It’s better to use the thicker ones first and only use the thinner ones if you need the extra height

A tripod may look like a straightforward piece of kit, but there are plenty of tricks you can use to get the most from it. More importantly, you’ll achieve the sharpest possible shots.

Avoid using the centre column

Most tripods come complete with an extendable centre column that can be used when you need a much higher shooting position than normal. The trouble is, it’s easy to become lazy, and rather than extend the tripod’s legs we simply bring up the centre column to the height we want – leaving the leg sections collapsed. However, this creates a far less stable platform from which to shoot, even when using the best tripod; save the centre column for when you really need that extra bit of height.

Use thinnest sections last

If you don’t need the tripod’s full height, you should extend the largest leg sections first. The most spindly sections are also the least strong, so using them instead of the thickest parts of the leg can affect stability. You want your camera’s support to be as sturdy as possible, so use the stoutest sections first.

Weigh it down

With your tripod extended and camera mounted on top, blustery conditions can destabilise your set-up pretty easily, so it’s a good idea to weigh everything down. This is easily done by attaching your camera bag to the centre column (there’s normally a hook to do this). If you can place your body between the prevailing wind and the tripod to shield it, so much the better.

Firm base

When you’re setting up, make sure you push the legs really firmly down into the ground, to give you as solid a base as possible from which to shoot.

If you’re on the beach, it’s tricky to maintain a solid foundation so try to find some rocks or stones on which to position your tripod legs, or consider using snowshoes to spread the load.

Get it level

While it’s not too much hassle to correct wonky horizons in Photoshop, get it right in-camera if you can. Some tripods have built-in spirit levels to help with this, or you can pop one on your hotshoe.

Don’t carry your camera on a tripod

When we’re swept up in the moment, we often want to move quickly between locations. Don’t try to save time by keeping your camera attached to the tripod and slinging it over your shoulder while you walk. Take a moment to pop it safely back into your bag, as you never know what might happen. It’s easy to forget that the camera is attached, and you can end up scuffing it along a wall, damaging the lens or the camera itself. In another nightmare scenario, you might not have tightened the quick- release plate sufficiently, and the next thing you know, you’re watching your camera as

it bounces along the ground.

Monopods

When shooting on locations like a beach it can be tricky to find a solid base for your tripod, so think about snow shoes and rocks on which to position the legs. Image by Phil Hall

Even with the best anti-shake systems, a monopod can add an extra level of stability to your set-up.

Use your tripod collar

Most decent monopods come without a head, but this shouldn’t be an issue if you’re using a longer focal-length lens, as most come with their own tripod collar. Screw your monopod onto the lens collar rather than to your camera body, as this allows you to switch between landscape and portrait-format shooting positions easily.

Rest your hand

Rather than holding on to the monopod itself and gripping it tightly, try to rest your left hand and arm lightly on the top of the lens if you’re using a long telephoto optic. This will greatly increase stability when shooting, as well as allow you to move the lens smoothly.

Image by Phil Hall

Flashguns

Flashguns (or speedlights/speedlites, as manufacturers would have us call them) can be an incredibly versatile piece of camera kit, allowing us to control and shape light, but we can sometimes be guilty of not making the most of them. With that in mind, let’s take a look at a few tricks that can transform flash images, form hard, directly lit photos to high-end shots with sculptured lighting.

Underexpose ambient light

Image by Kate Hopewell-Smith

A striking technique to try with off-camera flash is to purposely underexpose the ambient light of the shot, while the flash is used to light your subject and make it really stand out.

You’ll need to manually meter, stopping down the aperture by a couple of stops to force the camera to underexpose, then boost the power of the flash to compensate (you’ll need to set the flash to manual, too).

High sync function

Image by Kate Hopewell-Smith

Most cameras offer a maximum flash sync speed of between 1/160sec and 1/250sec. If you use a shutter speed faster than this you’ll end up with banding across your image. This isn’t an issue indoors, but if you want to use fill flash outdoors, or set a shallow depth of field, it can be restricting.

Some flashguns, though, feature a high-sync flash function. This allows you to use a much faster shutter speed (1/8000sec, for example) without the resultant banding of the shutter across the image. This is down to the flash firing for longer than normal, and the rear curtain of the shutter starting to close before the front curtain fully opens. This will be a dedicated setting on your flashgun.

Diffusion

Image by James Abbott

Light modifiers allow you to diffuse and sculpt the light for a much more pleasing result, with umbrellas and softboxes being the most popular choices.

Umbrellas are easier to transport and, in most cases, quicker to set up on location. There are two types to pick from. Shoot- through examples have a white translucent fabric through which you fire the flash to soften the light, while reflective options have a silver lining that you use to bounce the flash off and back onto your subject.

Softboxes also soften the light as the flash is passed through one or two layers of material and prevent light from spilling out the sides, although they can be a bit more hassle to set up.

Bounce flash

Image by James Abbott

Direct flash fired from the camera can cause unsightly shadows, especially if your subject is standing close to a wall. While off-camera flash can overcome this, it’s not always possible or realistic to set up lights remotely, so a quick fix is to start by angling the flash head (with the flashgun still mounted on the camera) and bouncing the flash off the ceiling or wall. This softens the light and reduces the shadows behind the subject.

Just remember, though, to avoid bouncing the flash off brightly coloured walls and look for neutral surfaces instead. Otherwise you’ll end up with an unflattering colour cast on your subject that will be hard to correct in post-processing.

Go off-camera

Positioning your flashgun remotely is a great way to achieve more sculptured lighting effects. Image by Phil Hall

Liberating your flashgun from the hotshoe and triggering it remotely is a great way to achieve high-end images. You can trigger the flash with a sync lead, via a (compatible) built-in flash on your camera, or – most people’s preferred option – via triggers.

Taking your flashgun (or flashguns for multiple light set-ups) off the camera means you’re going to need a suitable light stand for positioning your flash. Dedicated stands are better than simply using a tripod on which to mount your flashgun, and are relatively inexpensive. You’ll also probably need a bracket to hold the flashgun in place, but if you’re shooting outside it’s a good idea to anchor them in place to stop everything blowing over.