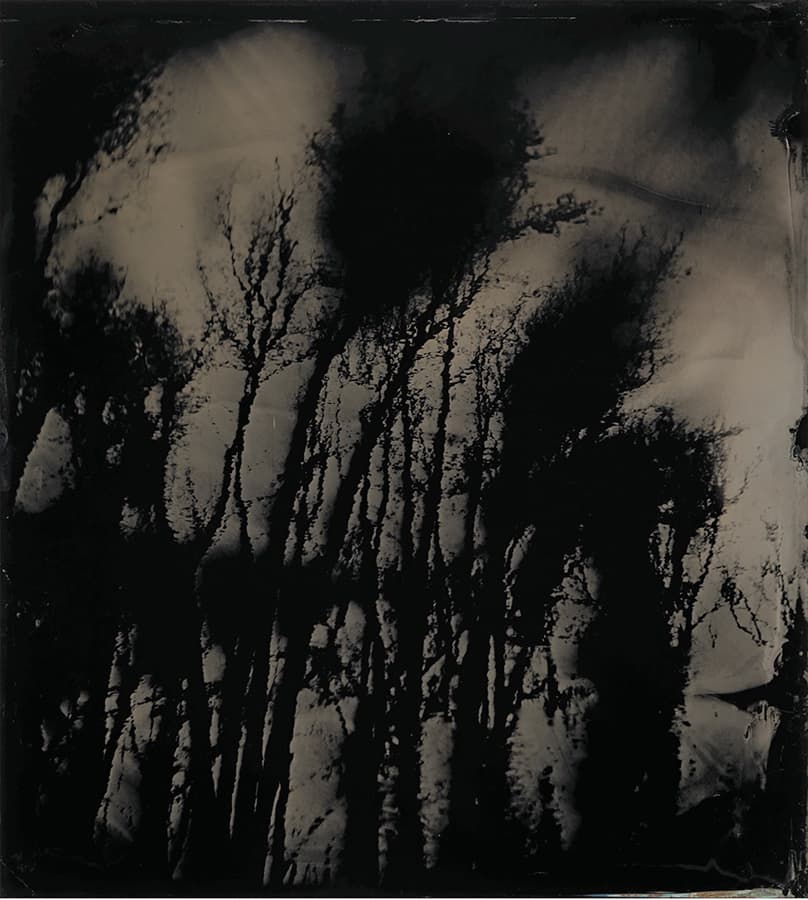

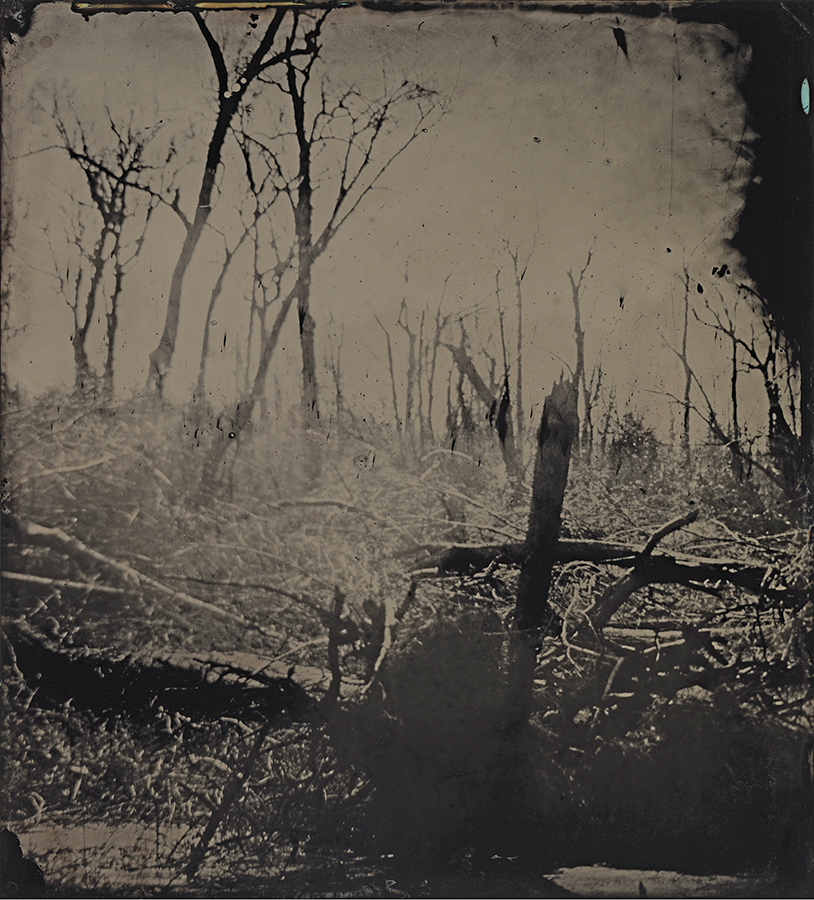

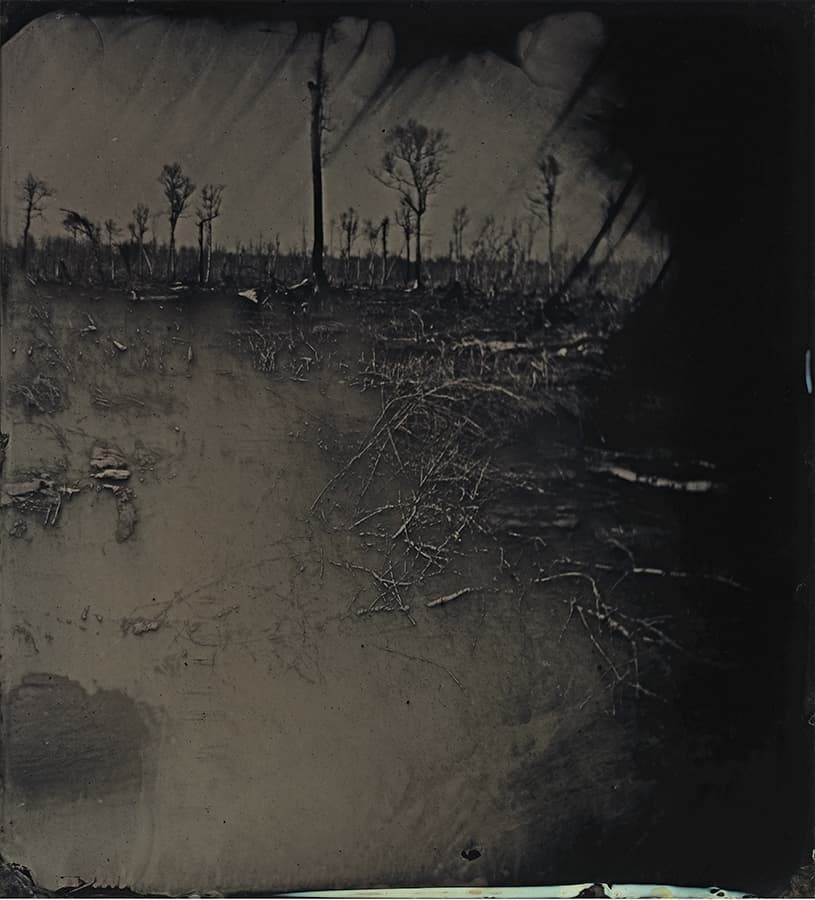

A set of brooding tintypes by celebrated American photographer, Sally Mann, of a swamp in America with a dark history, has won a top award. Peter Dench finds out more

On August 20, 1619, the English privateer ship White Lion landed in the British colony of Virginia, USA, at the ineptly named Point Comfort. The 20-30 enslaved Angolans would find none. Around 350 Africans were originally kidnapped by Portuguese colonial forces and packed onto the ship San Juan Bautista en route to Vancruz, New Spain.

Approaching its destination, the White Lion attacked, accompanied by the Treasurer and snatched some of the human cargo. The arrival of the enslaved marked the beginnings of two and a half bleak centuries of slavery in North America Less than 30 miles south of Point Comfort is the Dismal Swamp, an area comparable to the size of Mauritius. It’s very far from paradise.

As slavery escalated in the region, escaped slaves would often seek refuge in the swamp, preferring the challenges of insects, snakes, bears and other wild animals to the living hell of servitude. Communities of runaways (called maroons) established themselves in the swamp, constructing huts on higher ground and using the abundant wildlife for food.

Occasionally, slave catchers would try to infiltrate the swamps and flush them out with specially trained dogs. Working on the dead or alive theory, if the slaves couldn’t be captured, the colony would sometimes be surrounded and set on fire.

Catching fire

In June 2008, the swamp ignited when logging equipment caught fire. It burned for months across thousands of acres before finally being contained. On August 4, 2011, lightning struck and lit it up once more – it’s both literally and historically a combustible region. ‘By the time I was exploring it, vast fires, easily viewed from space, had begun consuming the swamp and continued to burn, forcing me to trespass past safety barriers warning of danger.

Thick smoke billowed up ceaselessly, not just for days or weeks, but off and on for years. In some kind of poetic, metaphoric righteousness, even the soil itself burned,’ explains photographer Sally Mann in her artist’s statement. The American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow described the quagmire as a terrifying place ‘where hardly a human foot could pass, or a human heart would dare’.

Mann’s feet and heart did dare, and hauling her large-format camera, she set out to explore the devastating wildfires consuming the Dismal Swamp. For her efforts, she collected 43 deer ticks across her body (taking hours to individually detach) and one of the world’s top photo-prizes. Mann’s series of tintypes, Blackwater (2008-2012) was announced on 15 December 2021 at the Victoria and Albert museum in London as the winner of the 9th cycle, Fire, of the Prix Pictet, the global award in photography and sustainability.

Entry to the award is strictly by nomination by a network of 300 nominators from across the globe, and more than 600 photographers were nominated. Mann, the recipient of the cash prize of 100,000 Swiss Francs (£80,000) was unable to attend the awards ceremony as she cares for husband Larry, now suffering from late-onset muscular dystrophy. Mann was also unavailable for an interview.

Founded in 2008 by the Pictet Group, there have been eight previous cycles of the Prix Pictet award to date. Each has highlighted a particular facet of sustainability: Water, Earth, Growth, Power, Consumption, Disorder, Space and Hope. Previous winners include Benoit Aquin, Nadav Kander, Mitch Epstein, Luc Delahaye, Michael Schmidt, Valérie Belin, Richard Mosse and Joana Choumali.

For each cycle, a book has been published and distributed worldwide. The hardback book, Fire (teNeues 2021) is big, beautiful and democratic, printed before the winner is announced. Mann has two images in the main body of the book and a page of ten images towards the back as one of the 12 shortlists (of 13 artists).

Chairman of the Prix Pictet jury, Sir David King prophetically remarks, ‘If ever there was a time for the Prix Pictet to take up the theme of fire, that time is now. Last summer we were inundated with images of fire at its most frighteningly destructive… These were not the harbingers of a crisis; they are the thing itself. This is it. The fire, long foreseen, has finally arrived. It is as if the future has somehow slipped into the present while we have been busy looking elsewhere and discussing long-time solutions.’

Born in Lexington, Virginia, 1951, Mann is perhaps best known for her intimate photographs exploring family, social realities and the passage of time. She began studying photography in the 1960s, attending the Ansel Adams Gallery’s Yosemite Workshops in Yosemite National Park, California and the Putney School and Bennington College, both in Vermont.

She received a BA from Hollins College, Roanoke, Virginia, as well as an MA in creative writing. A Guggenheim fellow and three-time recipient of the National Endowment for the Arts fellowship, Mann was named America’s Best Photographer by Time magazine in 2001.

She is the subject of two documentaries: Blood Ties (1994), nominated for an Academy Award, and What Remains (2006), nominated for an Emmy in 2008. Mann’s Hold Still: A Memoir with Photographs (Little, Brown, 2015) received critical acclaim, named a finalist for the 2015 National Book Awards and winner of the Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Nonfiction From the late 1990s into the 2000s, Mann focused on the American south, assembling photographs in Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana for her Deep South series (2005) and Civil War battlefields for Last Measure (2000), for which she made glass negatives using a large-format camera and an antiquated method – the wet plate collodion.

One of the earliest and most technically complex photographic methods, invented by Frederick Scott Archer in 1851, it involves coating a glass plate with a syrupy substance called collodion and a light-sensitive solution of silver salts. The negatives made of glass, rather than paper, brought a new level of clarity and detail to photographic printing. Mann found that working with the historic method helped infuse her pictures with a sense of the past.

Working with tintypes

Continuing with an historic method, Mann made her Blackwater series on tintypes (producing a 38.1×34.3cm/15×13½in plate), underexposed collodion negatives that read as positive images against a dark background. Produced on a sheet of black lacquered metal, tintypes are one of a kind. Also known as a melainotype or ferrotype, the tintype peaked in popularity during the 1860s and 1870s. They were utilised in documenting soldiers and battle scenes during the American Civil War (1861-1865).

Views from the Wild West were captured by wandering photographers working from covered wagons. Tintypes remained popular at carnivals until the 1890s – the lacquered iron support (there is no actual tin used) was resilient and did not need drying. They could be developed and fixed and handed to the customer only a few minutes after the picture had been taken.

Mann’s images are stark, beautiful, rich and brooding, the deep black liquid-like surface echoing the burnt trees, billowing skies, murky swamp and even murkier history. The images were first exhibited as part of A Thousand Crossings, an exhibition of more than 100 landscapes that premiered at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, in 2018.

Mann, who lives on a 400-plus-acre farm under vast skies tucked into the Virginia hills says, ‘For years I have been examining the racial history of my homeland, the American south, viewing the land as a vessel for the memories of the complex struggles enacted upon it. The fires in the Great Dismal Swamp seemed to epitomize the great fire of racial strife in America— the Civil War, emancipation, the Civil Rights Movement, in which my family was involved, the racial unrest of the late 1960s and most recently the summer of 2020.

‘Something about the deeply flawed American character seems to embrace the apocalyptic as solution, the Fire Next Time, fire as a curative. Perhaps we do need to tear it down before we can rebuild, perhaps fire, uniquely, does cleanse and restore, yielding the small green sprigs and vines starting now to re-vitalize the swamp, offering hope for restoration.

But fire does not destroy memories and no matter how our laws are revised to be more equitable or how our tortured racial past might somehow be mitigated or how completely the Great Dismal Swamp is engulfed in flames, no one will forget,’ she adds. Mann’s repurposing of an historic photographic process cleverly tells a chilling contemporary story. The Blackwater series is a testament and reminder.

Related Articles:

Sally Mann wins fire themed Prix Pictet prize with tintypes

French photographer scoops £65k Prix Pictet prize

Five-year project on global food consumption wins Prix Pictet prize

Colossal camera creates ‘largest tintypes in the world’ for Photo London