Top photography teacher Joel Grimes explains why it’s not always the best photographers who make money – but the most persistent and smart at marketing.

Joel Grimes by his stand at the Xposure expo

Joel Grimes has been a commercial photographer for over 30 years, with particular success in the fields of advertising and portraiture.

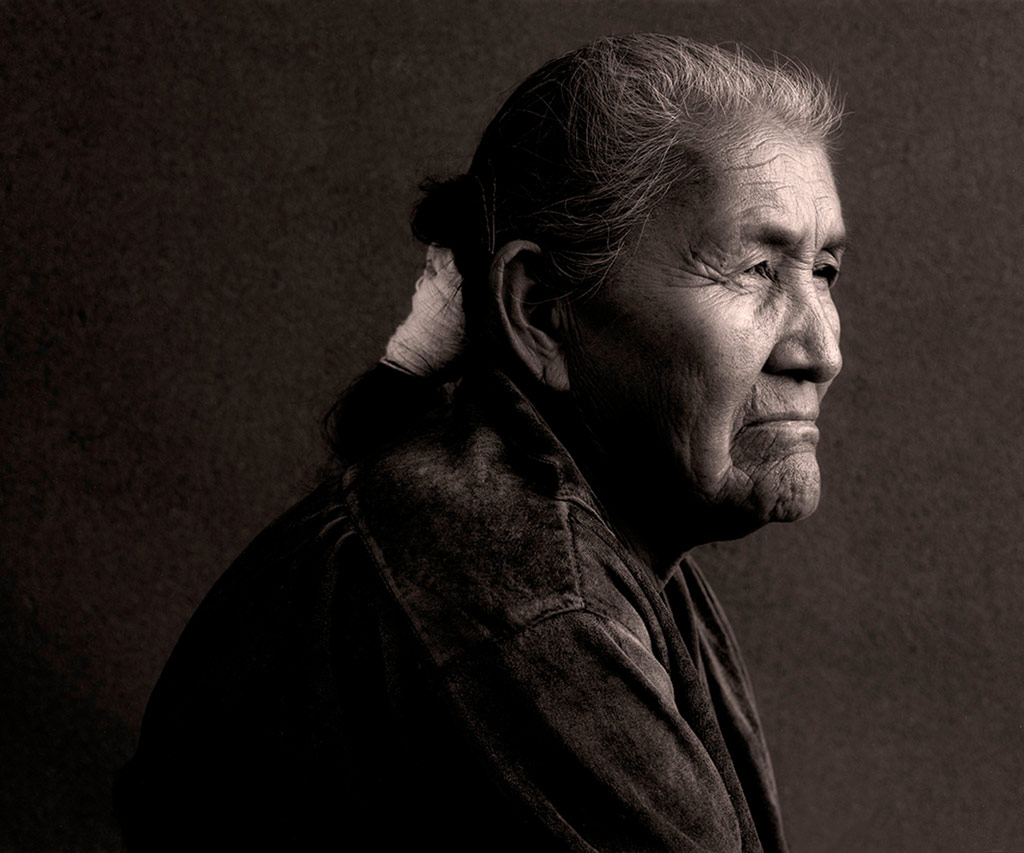

In 1992, his first coffee table book, ‘Navajo, Portrait of a Nation,’ led to an 18-month solo exhibit at the Smithsonian American History museum. Joel’s also a Canon Ambassador of Light, yet he’s equally well known as a photographer teacher.

Joel’s a passionate believer that it’s still possible to make money from photography, even in very tough and competitive genres like landscape.

Joel’s stand at the Xposure Photo Expo was packed with people hoping for commercial photography advice, but he found time to share some tips with deputy editor, Geoff Harris.

What’s your background as a photographer?

I studied photography at the University of Arizona. Although I was very drawn to landscape shooting, a charismatic professor got me interested in portraits, as well as seeing the work of other great portrait photographers.

Eventually, a buddy and I set up a studio in Denver, and he taught me a lot about lighting – I’d also studied art history, so I was interested in the techniques of the old masters.

To cut a long story short, I got into architectural photography and then portraiture, via advertising. Some mom and dad ‘testimonial shots’ I took for a campaign were very popular and launched my advertising career.

Luti, a Navajo woman, Tuti, Arizona. Credit: Joel Grimes

Why and how did you get into teaching?

If you talk to my wife, even 30 or 40 years ago, I would always have my studio door open and was happy to show what I was doing to anyone who was interested. I was fine to share my secret sauce.

This was quite unusual, as during the 80s and 90s photographers were very tight-lipped about how they did things, but I was never like that.

This approach naturally opened the door for me when photography started to explode during the digital era, and teaching opportunities arose.

It grew from one client to 45 speaking events a year, and then I began offering tutorials and training courses – starting off with tutorials on DVDs before moving online.

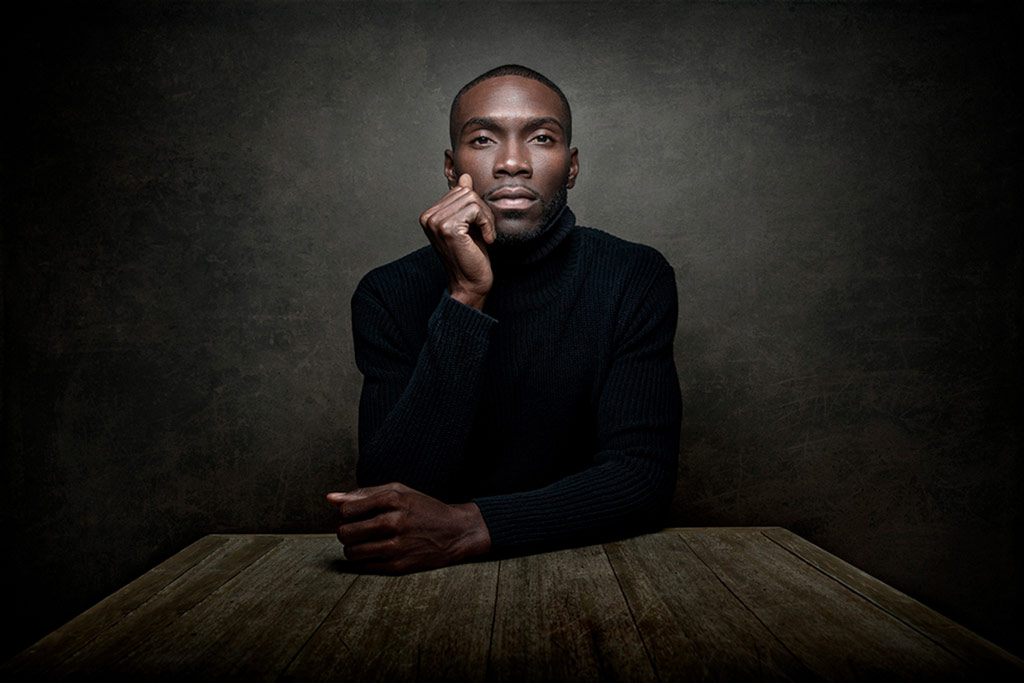

Greg Wildman, cowboy, Prescott, Arizona. Credit: Joel Grimes

Now we have a team that markets my courses and we send out 5 million emails a month. I don’t go YouTube much, we find that mailing lists work best – it’s now half a million strong.

So let’s cut to the chase – can people still make money from most photography genres?

Yes, absolutely. I am probably the loudest voice in the industry saying that is possible to make a living with a camera. And here’s why. If you throw a rock in say Denver or Phoenix, for example, you will hit a building that needs photography.

Kerron Clement, Olympic gold medalist, 400m hurdles. Credit: Joel Grimes

Photography needs are surrounding you and it’s about learning how to go after them by sharpening your business skills.

Let me give you another example. You are driving down the road and see a billboard, featuring great photography. Somebody took that picture and got paid for it. So when starting out I’d I ask myself – what is the path they took to get to that place? I learned that path and now have billboards all over the place.

Most people don’t understand this process. Work doesn’t fall in your lap. You have to push yourself into the presence of the people who make the decisions on hiring you to do that.

Here’s the other thing. It’s not the best photographers who get hired, it’s the most persistent ones. It’s a weird thing. When I got hired by an agency, it was not because of how good I was, but because of a crisis.

The art director or creative director at some point will have a list of go-to photographers and because some kind of problem or emergency has arisen, they will need a photographer at short notice. Because I had been so persistent, my name popped up. For years I lived off this.

Advertising and commercial photography is one thing, but what about people hoping to make money from really tough genres – landscapes, for instance?

Yes, again it’s possible. Think about it this way. Let’s say we look for a landscape photographer that is successful. They are making a living, and they are there.

The reason they are at the top is twofold: they take more pictures than the average person and they learn how to market them. These are the two things they probably do better than anyone else.

So with time, they built a good body of work but they learned how to market it. If you can also market your work effectively, you can make money in any genre you can think of. I know a lot of landscape photographers who are making money.

You can try pitching to the big galleries and chasing the big money, but what about selling prints at open art fairs – they are all over the US, and I am sure they are popular in the UK and Europe too.

From what I’ve seen, the landscape photographers who get out there and target art fairs are probably making more money than those who try and get their work in galleries. They working on volume, selling prints at, say, $300 a pop.

The psychological side is important too. Landscape photographers might have to get beyond being shy, insecure, their fear of rejection etc, but an equally big problems is misinterpreting the market.

Elena, archer, Italy. Credit: Joel Grimes

What about the difficult subject of setting pricing?

Most photographers tend to generally undervalue their work. Studies have been done with landscape photography. You take a landscape print and put it up for, say, $300. People think, ‘hmm, that is kind of cheap.’

Then the next week you put a $1000 price tag on same print and people think wow that must be a pretty good print, I love it, and seems like a great investment!’

You’ve instantly put a greater value on it. It’s a complex subject, and I’ve done a video on it here.