Stuart Franklin is better placed than most to examine the human ‘need’ to document the world, as he now combines his photographic career with teaching. ‘I’m a professor of documentary photography in a university up here,’ he explains down a Skype line from Norway. ‘I run a BA and a Masters programme in documentary photography. I do it 50 per cent of the time – of which half is spent on research and the rest of the time I spend photographing.’

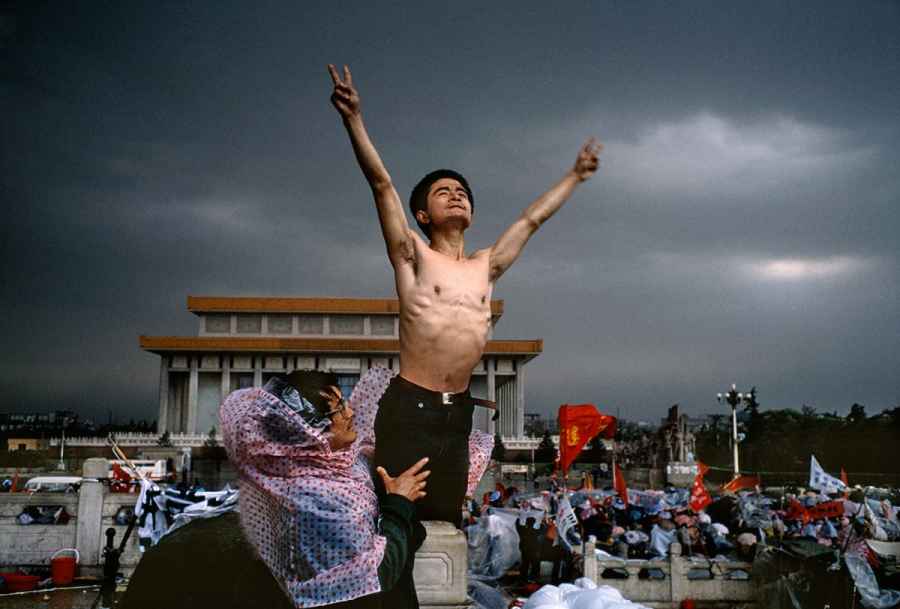

The recent result of Franklin’s research and his views on documenting the world are contained in his new book The Documentary Impulse, which is an in-depth examination of humankind’s desire to document – from cave paintings to today’s digital world. His suitability for authoring this tome is reinforced when you consider that his documentary career has included covering events such as the 1983 Nigerian exodus, the 1985 Heysel Stadium disaster in Belgium, the conflict in Northern Ireland, famine in Sudan in the mid-1980s, as well as the events in Tiananmen Square, China, in 1989. But more of that later in the article.

Initial interest

Franklin’s initial interest in photography dates back to his late teens. ‘When I was about 19, I lived on Vancouver Island in Canada, having hitchhiked across America,’ he explains. ‘I bought a Yashica B twin-lens reflex camera in a second-hand shop in Victoria and travelled down to Mexico and central America. I just enjoyed wandering around, seeing and using the light. It seemed like a really joyful thing to do and the people were amazing. It was all [shot] in black & white – I didn’t shoot a single frame in colour.

‘When I came back and developed the images they were absolutely dreadful. I took them to a guy called Len McComb, a painter who was running a foundation course at Oxford Polytechnic, and he took me in. I didn’t have any “A” levels and, bless him, I carried on from there.’

Fittingly, Franklin got his early inspirations from photography books. ‘I remember finding Mary Ellen Mark’s first book, Passport, in a charity shop for 10p and thinking it was a wonderful body of work. It was kind of harsh and grainy, but what was fantastic about the work to me was her sense of curiosity, the energy and also the fact that she’d been to all these places and travelled. Marc Riboud’s Visions of China was a book I got quite early on and this kind of very cool, impressionistic kind of work was lovely. It was very simply done on a 50mm lens; I loved the disarming simplicity of it. I was in heaven in the library, and I was very aware of that kind of aesthetic of people like Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Doisneau and so on.’

The most influential documentary photographer

Corporal ‘Snowy’ Forbes, of the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers, on exercise in the hilly country near Episkopi, Cyprus, 1987

In his book, Franklin cites Cartier-Bresson as probably the most influential documentary photographer of the 20th century. When reminded of this he laughs. ‘I only laugh because he said in an interview in 1971 that he was not interested in documenting and that he was one of the world’s worst reporters,’ says Franklin. ‘But you only have to look at the picture he took of the Belgian Nazi collaborator (and Gestapo informer) in Dessau in 1945 to realise what an amazing reporter and documenter of life he was. He was dealing in this kind of dialectic of form of content and was always trying to resolve the problem of loving the form and getting occasionally interested in the content. So, all of that was hugely inspiring to me.’

But aside from inspirations, what does Franklin think is the most powerful thing documentary photography can do? ‘I talk in the book about Tolstoy’s idea about art needing to “infect” – to get inside us. I would probably still uphold that view, although I probably wouldn’t use the word that Tolstoy used. I think that images have got to touch our soul somehow, and we’ve got to feel our way into them and be moved by them. You never quite know how that’s going to happen. It’s a bit like a pop song: you never quite know how suddenly a song is going to catch on and people go, “Wow! That’s amazing. I’ve been singing that in my sleep”.

‘Things do catch on and I think that that’s, almost subliminally, what documentary photographers set out to do – to make a sort of clear transition between what is a particular moment in a particular place to something that’s much more generally felt.’

Impact of the ‘Tank Man’ image

Perhaps the best example of one of Franklin’s images that ‘caught on’ is his famous ‘Tank Man’ photograph from Tiananmen Square, China, in 1989, when he, and other photographers, leant out of hotel windows to capture the now iconic stand-off between a lone man in a white shirt and a line of Chinese Army tanks.

‘It didn’t really become that important for a couple of days,’ Franklin recalls. ‘It was only after it got on to television that people woke up to the picture and television drove its future as a picture. It was convenient from the point of view of [then US President] George Bush, who was the first person to publicly champion the photograph when he saw it. It was convenient for him because it enabled him to say, “Oh, look, they’re showing restraint,” and it suited the Chinese as they could carry on business as usual. But on the other hand it became a very powerful symbol for people facing the power of the state, the power of oppression and so on. So it was a sort of multi-headed hydra that was born through that picture.’

The need to feel

While some might struggle to see beyond the stereotype of the hard-nosed documentary photographer, the legendary English photojournalist Don McCullin has been quoted as saying, ‘photography isn’t looking, it’s feeling.’ So does Franklin agree?

‘Totally,’ he says. ‘I’ve been in tears when I’ve been photographing. I think if you didn’t feel anything then you may well be in the wrong job. If you can’t instil [feeling into] some of the more poignant moments that we, as documenters, are privileged to experience, then maybe you should do accounting or something.’

But is there any point at which a photographer should intervene in a situation? Franklin explains: ‘I’ve done that a few times – got blankets for people who were shocked by a particular event or lent them my car. We do it all the time. I think I was in Gaza and somebody wanted to go to the hospital, and I had a car and a driver – of course, not many people do there – so I became the ambulance. But that’s the sort of thing that journalists do everywhere.’

As well as imbuing their photographic work with feeling, should a photojournalist ever put down his or her camera? Franklin says: ‘It depends on the situation, and I think one always has to be sensitive to people’s feelings around you, particularly at things like funerals that can be very moving events. If you get a sense you’re imposing in some way, then you’d stop photographing; I’m sure I’ve done it a couple of times. I think that most people out there working in the field, who are experienced, do know when to step back a bit. That’s unless whatever is happening is so critically in the public interest that you’d carry on, but it’s a decision you can only make in the field.’

Key landmarks

As for his personal career landmarks, Franklin reflects: ‘I remember doing a story for The Sunday Times Magazine on the Peto Institute [in Hungary], which is an institute that helps children who suffer from cerebral palsy. I remember being in a café and a lot of people would come over from England, where these children were often treated as “vegetables”, and there [at the institute] they were helped to gain some mobility. Seeing this mother’s face when her young child walked for the first time was incredibly moving. I find it very difficult to talk about it, even to my students, without kind of cracking up somehow.

‘I think it’s these little moments of joy that are perhaps more resonant than tragedy, which in a sense one tries to blot out… dead babies or things that you can do nothing about – people who are going to die. But the moments of extreme hope and joy I think are very memorable.’

Franklin also believes that while photojournalism can be very dark at times, it can also have a sense of humour. ‘Doisneau wrote very succinctly about this kind of “lighter touch” and way of seeing – and I think there’s a lot of humour in his work, but in quite a kind and interesting way, particularly the work he did in Paris,’ he says. ‘There’s a sort of lightness that he and many other photographers have brought to their work that is special. I don’t think photojournalism has to be dark at all, but on the other hand one can’t gloss over the fact that there is a lot of tragedy out there.’

Advice for aspiring documentary photographers

As for advice for those wanting to carve out a career in documentary photography, Franklin states: ‘Like anything [else], you’ve got to be prepared to put a lot of time into it because in most of the best documentary work that we see you can feel the time that has been spent in it and the sense of being there. If you’re not prepared to spend time and give to the reader or viewer the sense of being there, then you might as well go and do another job.

‘You can be conceptual in certain ways and you can turn up for ten minutes, but I think a lot of the pictures that have survived are ones in which you can feel the time to some degree. I mean not always – Richard Avedon said he felt closer to people when he only spent a few minutes with them, and he didn’t want to spend any more time with them. A lot of his portraits, say, from the American West, are very powerful, so it’s not a sort of “concrete rule”. Avedon is an interesting exception, but in general it is worth spending time.’

Hopes for the future

Unlike some, Franklin does retain a bright outlook for the future of documentary photography. ‘I think it’s a hugely important medium and, because there are so many gaps in what television can deliver, there are so many more opportunities in photography to tell stories that people wouldn’t otherwise see,’ he says. ‘I know that it’s very hard to whet the appetite for this. It’s very hard to get people to buy work and invest in photography, but there are a lot of grants out there and there is a huge interest on the part of the public.

‘I mean Nick Serota, who’s just left the Tate galleries after nearly 30 years [as director], said in an interview that he expected two million people to go to the Tate Modern and already more than five million are going a year. They’ve invested heavily in photography and in the prospect of people visiting the collections. It’s just about how it’s organised and articulated. But I think the important thing is to find the power inside yourself to go out and do meaningful work and to stick with it so it has coherence.’

All images by Stuart Franklin/Magnum Photos, used with permission.

_______________________________________________________________

About Stuart Franklin

Stuart Franklin is an award-winning photographer who began his career shooting for the The Sunday Times Magazine and Sunday Telegraph Magazine before joining the Sygma press agency in Paris. He has been a member of Magnum since 1989, and was president of Magnum from 2006 to 2009. He is best known for his ‘Tank Man’ image shot in Tiananmen Square, China, in 1989. He now spends half his time teaching documentary photography and the other half on a mixture of personal projects and assignments.