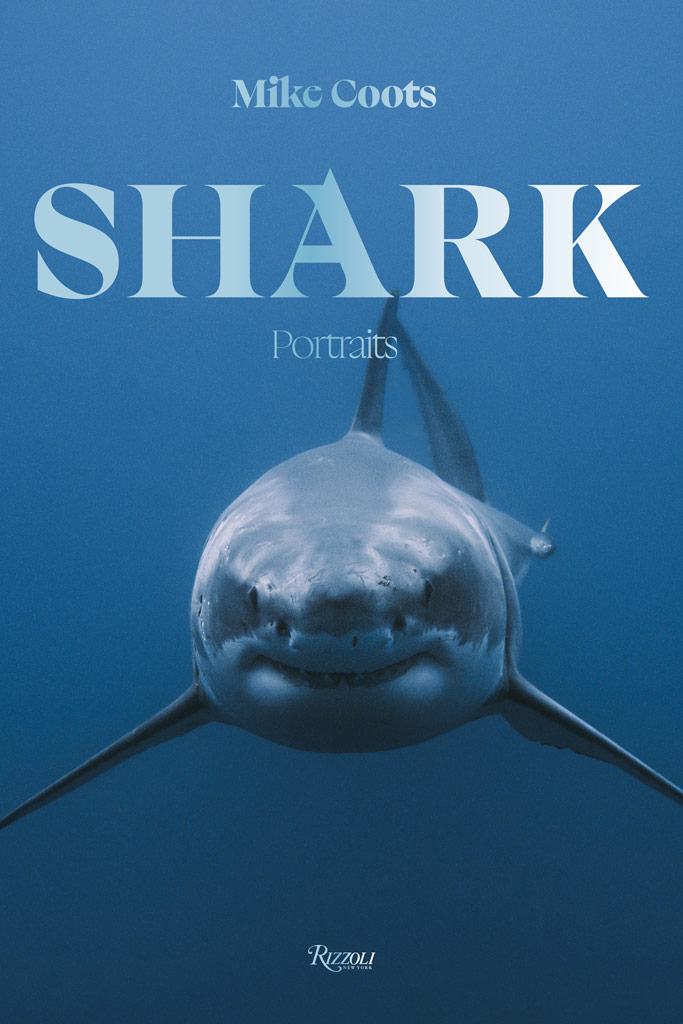

Being attacked by a shark would put many people off going back into the ocean. But for Hawaiian surfer Mike Coots, 44, the near-death experience led to a new life as an underwater photographer working to understand and to help protect the majestic but threatened apex predator. He tells Graeme Green about his venture into wildlife photography, shark portraits and his new book Shark: Portraits.

Trigger warning: detailed mention of shark attack experience

Your new book is called Shark: Portraits. Are sharks open to having their portraits taken?

Some sharks like the camera. They’ll come close and seem really interested in you and your camera. But some sharks are skittish. With tiger sharks, a lot of people jump in the water and start chasing after them. You need to give them time and let the animals come towards you. That’s when you get the best photos.

What kinds of portrait techniques do you apply to sharks?

When I’m underwater, I’m mainly trying to nail the focus and composition. It’s more in the post-production. I gravitate towards images where I can see the shark sort of having a human characteristic: a smirk, a smile maybe, a highlight in the eyes that catches the light. I look for those same things you would if you were going through a portrait session with a person.

I’m trying to get people to love sharks. Hollywood has done a good job of showing the scary side of sharks. It’s refreshing to show the other side.

What is it you find fascinating about sharks?

After I was attacked, I was more curious about shark attacks than the sharks themselves. I was curious why I got attacked. I had a lot of questions and read a lot of books.

The first time I went diving with sharks, I saw a whole other world. I’d spent a lot of time, as a surfer, above the water. But when you’ve got eye contact and you’re below the water with a shark, it’s mesmerising. They’re beautiful creatures. You’re looking at a living dinosaur.

Can you talk through what happened in the attack?

It was in Kaua‘i, in 1997. I was 18 at the time. We have a good surf spot on the west side of the island. I’d been in the water less than five minutes. I was paddling for a wave. I didn’t see a fin breach or have any forewarning – I was just blindsided. It grabbed onto me – a big tiger shark, around 12 to 14 feet. I stuck my right hand into its mouth to try to get my legs out. That didn’t work, and I felt a huge amount of pressure – zero pain, but a lot of pressure. The shark lifted me out of the water and ragged on me back and forth. It felt like I was watching myself in a movie. I punched the shark in the nose. It let go as soon as I hit it a few times.

Did your survival instinct kick in?

Yes, it was a primal instinct – “A large animal is attacking me and I need to fight back.” I got back on my board and started paddling in. My right leg did a weird ‘shake’. I thought the shark was finishing me off, but I looked behind me and my leg had severed right off, big squirts of blood coming out every time my heart beat. Fortunately, a wave came and I rode it all the way to the sand. My friend Kyle used my board’s leash as a tourniquet and saved my life. I went in and out of shock as we drove to the hospital. I woke up a day later as an amputee, and spent a week in hospital and a few weeks bedridden at home. I was back in the water in a little over a month.

At Tiger Beach, the Bahamas. This great hammerhead shark is a large female named Pocahontas. Surviving a shark attack prompted Mike to learn about the importance of sharks. Photo: Mike Coots

Was there a chance you’d never go back in the ocean?

No. I knew it was a statistical anomaly that I got attacked. The fear of losing out on good surf and being with my friends in the ocean was much greater than feeling I’d be attacked by a shark again. The second I could get back in the water, I did.

Do you have any idea why the attack happened?

When we turned up at the beach that morning, there was a foul smell in the air. I think there were dead fish in the water. The shark probably thought I was a turtle or something. The water was murky that day as well.

What made you channel your experience into protecting sharks?

One thing led to another. After the attack, I was out of the water for a while. Sitting on the beach, I fell in love with shooting photos of my friends surfing. That transformed into going to art school to study photography, and then that transformed into learning about the importance of sharks on Youtube. Later, I got into the policy-making side of things. I’ve talked to congress (in Washington?) about shark legislation. I’ve been able to speak out as a shark attack survivor and use the irony of my shark attack, along with science, to say why we need to protect sharks.

Why are sharks so endangered?

One of the biggest threats is shark fin soup, a delicacy in Asia, which has no nutritional value. It’s barbaric. People go out to sea, catch the sharks, and then cut off the fins, which are used in the soup – the rest of the body is thrown overboard.

Another big issue is bycatch from the commercial fishing industry. Sharks are inadvertently caught in longlines for tuna and swordfish.

For shark fin soup, there are upwards of 70 million sharks being killed each year. For the commercial fishing industry, I don’t know the number because the industry’s hidden in secrecy.

How vital are sharks to healthy oceans?

As a keystone species and apex predator, they get rid of the sick, diseased, dying and weak, and they keep the food chains below them in balance, so other populations don’t get wildly out of control. If we don’t have sharks in our oceans, we won’t have healthy oceans or a healthy planet.

What’s the best location in the world for photographing sharks?

For great whites, it’s Guadalupe Island in Mexico. For tiger sharks, it’s either Fuvahmulah in the Maldives or Tiger Beach in the Bahamas.

Fish are Friends. Tiger shark at Tiger Beach, the Bahamas. Mike says Hollywood has done a good job of showing the scary side of sharks and it’s refreshing to show the other side. Photo: Mike Coots

Are sharks difficult to photograph, when you need to keep a close eye out?

Sometimes you can get so locked on to what’s in your viewfinder that the space around you disappears. It won’t be the shark in front of you that you’re photographing that’s a problem – it’s going to be the shark that you don’t see. It’s good to pull your head away from the camera regularly to get a good visual sense of what’s around you.

Since the first attack, have you had any other close calls?

I was in an underwater submersible in Mexico, a cage that moves with propellers. You have a guy driving, and you can hang half your body out the front. I had a great white shark, who was irritated by those propellers, come straight at me – it was within millimetres of my face. I thought it was going to bite my head off. I couldn’t talk for a while after that.

The ocean is unpredictable and wild, but I control everything that’s in my power. If you know the sharks are getting agitated or the water is getting murky, you get out of the water. You never want to push yourself, or say “Five more minutes, I’m getting the best shots.” Safety is Number One – photography is second.

Shark: Portraits by Mike Coots (Rizzoli, £42.50) is out Sept 19. For more on Mike’s work, see sharksbymikecoots.com and Instagram @mikecoots

Featured image: Mike taking another of his stunning pictures, of a tiger shark. Photographed at Tiger Beach, in the Bahamas

Wildlife photography holidays

Test and improve your wildlife photography skills on one of our Wildlife photography holidays. Led by experts, we have a range of photo trips coming up in the UK and around the world. See all upcoming trips here.

Related reading:

Best waterproof cameras and housings

Revealed! The world’s best underwater photographs

How to be an ethical wildlife photographer

Best cameras for wildlife photography

Follow AP on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube and TikTok.