The Dream, which is currently being exhibited at the Bronx Documentary Center, covers the past five years of images that Bucciarelli has shot throughout the world, highlighting the plight of refugees. His travels have taken him from the Italian island of Lampedusa, to Syria, Turkey, Iraq, Egypt, Serbia, Macedonia, and to the small Greek island of Lesbos, where refugees continue to arrive from Turkey by the boatload every day.

We recently caught up with him to ask about his career and this latest project.

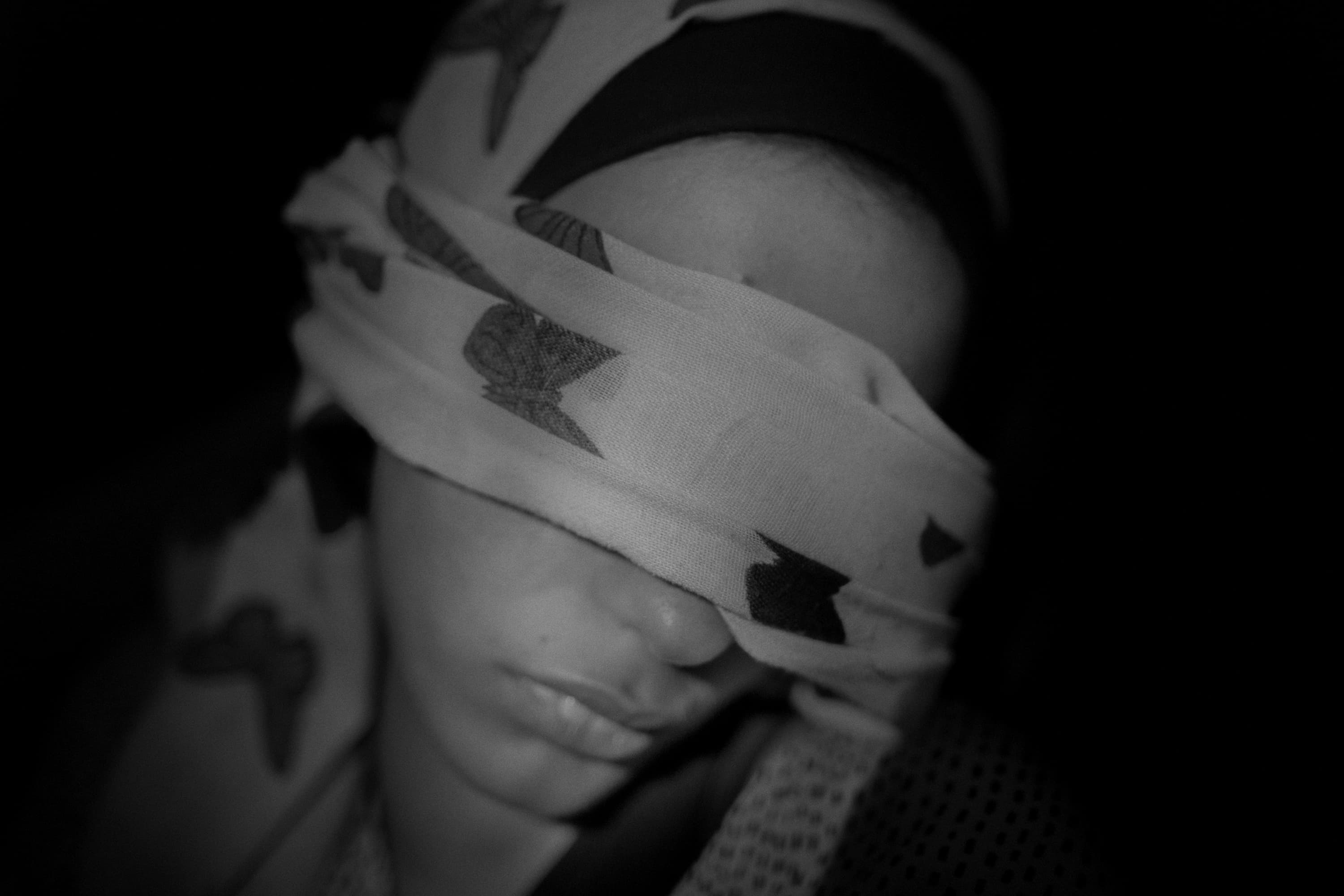

A woman from Syria rests on a bus crossing Serbia, bringing her from the Macedonian north border to Belgrade, Serbia’s capital city.

How did you start out as a photographer?

I originally got a degree in telecommunications in 2007 and worked for a while as an engineer. In 2008 I started becoming interested in photography and did some reportage and exhibitions in an amateur way. At the end of the year, inspired by a workshop by [war photographer] Philip Blenkinsop, I decided to quit my job and try to work as a photographer.

So I started travelling and the turning point was when I spent a month covering the 2009 earthquake in Italy, collaborating with Italian press agency La Presse/AP. When I came back they gave me a contract as a staff photographer covering sports, Milan fashion week, political events, etc. It was like a dream for me. After two years I decided to quit the agency to work freelance.

When did you end up specialising in war photography?

In 2011 I went to Libya a few times on assignment and covered the final battle there. I took a picture of Gaddafi on the day of his death, and that was a turning point for my career as a freelance photographer.

I continued to cover the Arab Spring and in 2012 spent a month covering the war in Syria. I received the Robert Capa Gold Medal and the Pictures of the Year International award for the work I did there, and this was another major turning point in my career.

A Sudanese refugee sits on the dock of the Sicilian port of Augusta (Italy) waiting to be transferred to the first reception area, June 23, 2015.

What inspired this project on the refugee crisis in particular?

In Libya, when I was covering the fighting in Benghazi, I remember hundreds of people waiting in camps. These people were from Bangladesh or other African countries and had come to work in Libya, but when they arrived they immediately entered the conflict zone and became refugees of the Arab Spring. So, at that time I decided to keep an eye open for the refugees of the Arab Spring. I travelled to different countries such as Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Syria, Turkey, and to the Balkans, and since 2011 have been taking images of the refugee crisis.

After last summer, I looked over all my work that was ready to be published and talked to FotoEvidence Press in New York, which decided to do a book about all these stories. From the book the exhibition was born. We have just finished the edit of the book, covering the past five years, which will come out in the first week of May.

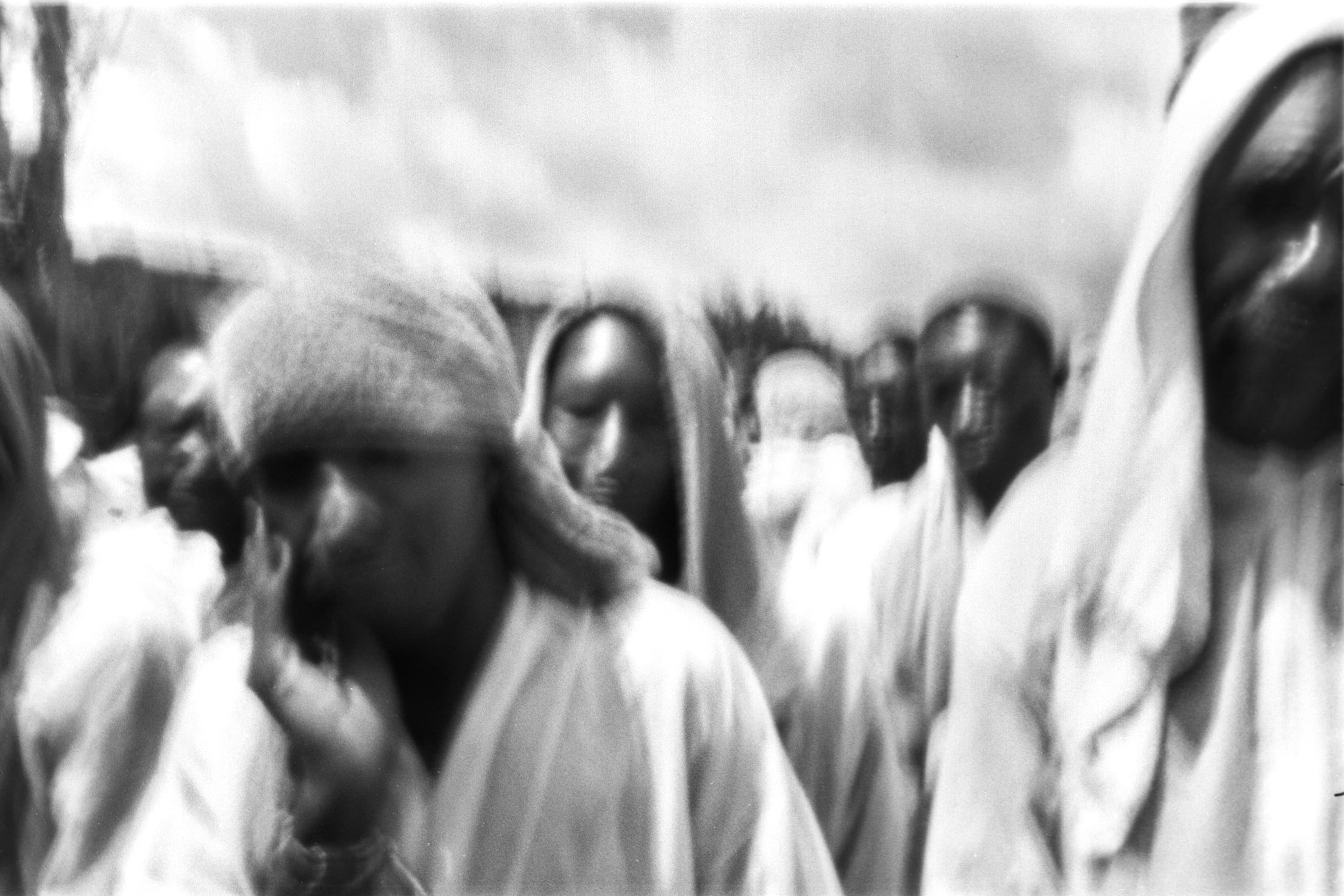

Afghan refugees wait to be registered out of Moria camp at the Greek island of Lesvos on October 12, 2015.

Am I right in thinking ‘The Dream’ is a crowdfunded project?

Yes, we were wondering how we would get funding to publish the book, because it’s not like a book with the best pictures across the past five years; it’s a book with a specific idea. So we decided to join forces with the crowdfunding campaign [Kickstarter]. We asked for $26,000 and got $30,000, so we got enough money to do the book.

What are you hoping to highlight with the images in the book? Are you hoping to change people’s opinions or show something in particular?

Yes, absolutely. During the past year we have been overwhelmed with images of refugees escaping, or images of refugees crossing countries, so what I tried to do is give a different focus to the refugee crisis.

The book is called The Dream – the dream means the engine for the refugees when they start fleeing war, when they start to escape from the conflict zone. The only thing that gives them the power, the hope to escape, is the dream – the dream to get a family, the dream to find a job, the dream to escape as far as they can from the war.

So it’s like a more conceptual way of storytelling. But at the same time, we are talking about a breaking news event. We are talking about a very immediate crisis, so I tried to get a [balance] between photojournalism and conceptual pictures.

The Dreamers

How are you received by the refugees? How do they respond to you taking their images?

Everyone was great. There are a lot of people escaping from Syria who know very well the importance of photojournalism, because this is the way the world can know something more about them.

The point is, when you’re trying to get a picture that has empathy, you have to feel that empathy when you are getting the picture, so you have to spend time with them so they trust you. The difference between just a good picture and one that becomes iconic is the empathy you feel when you are shooting.

What would you like people to know about the refugee crisis if there’s one thing your images could tell people?

First, that they are victims of war, or anger, or crime.

Another thing is that I want people to treat them as human: that’s the most important point. In Europe, after the past six months, there are a lot of countries building barbed-wire fences because they don’t want the refugees coming into their country, but they have to understand that they don’t want to come into your country, they are escaping the war.

It’s like Italians when they came to South America. It’s migration – and that’s the human story.

A Syrian family weeps tears of joy after reaching, on a rubber boat from Turkey, the village of Skala Sykaminias located on the northeastern Greek island of Lesbos, on October 10, 2015.

Can you tell us about the kit used? You said you used a pinhole camera for a lot of the images.

Yes, a friend of mine made a pinhole camera for me to test for him, as he wanted to start production of them. When testing the camera I realised it was really good, so I decided to start shooting with it. The kind of image that pinhole cameras produce is timeless. It’s a bit different from the photojournalist images that explain what is going on: pinhole images transmit more empathy, the feeling of what the refugees are feeling during their trip and during their process.

Migrants and refugees coming from Sub-Saharan countries are seen in line for the identification process at the dock of the port of Messina (Italy) on July 4,2015.

How do you maintain impartiality in war photography? I imagine it’s very difficult to tell both sides of a story.

Yes, it’s difficult to tell the story from both sides. For example, I’ve never been in Syria from the regime side. It’s not easy for me to go there now because I’ve been working in Syria on the rebel side and have been published a lot. If you want a 360-degree [perspective] of the situation it would be great to visit both sides of the story, but sometimes we have to take a side. We are journalists and we have an idea of what is going on over there – that’s the reason why we want to go and cover it, and we have to be clear with ourselves why.

With the Syrian war, I went to the rebel side rather than the Assad side because I was thinking, and am still thinking, that Assad did a shit in the country, so I wanted to talk about the story of the poorest people who were getting bombs on their heads.

When I covered the Libyan war, I decided to go to Libya to cover the war from the rebel side because at the time all of Libya was fighting for their rights against a dictator. When a journalist decides to go somewhere, they have to decide which side to cover, and there needs to be a reason to go on the one side and not the other – that’s probably the way the journalist sees the story.

Syrian refugee children play in the reception tent at the dock of the city of Augusta (Italy) after having been registered by the Italian authorities on June 10, 2015.

Do you ever put yourself in danger? How do you decide what levels of danger are acceptable?

You are covering a war, so you are always in danger. That just means when you are at the frontline and people are shooting at you, you can be three kilometres from the front and something can happen, or you can cross the border and they can kidnap you. When you are covering conflict, you are in danger, but everybody can choose the level of danger they want to take.

There are no images that are important enough to die for. You know perfectly well you’re in dangerous situations and something can happen, but the idea is to try to minimise the risk.

I try to do no more than one-and-a-half months in a conflict zone, because I know that after that time I’m going to lose the fear. After a month and a half, I always come back to get the reality again, because when you are working a lot in a conflict zone it gets to be normal for you, and it’s not normal, so it’s important to balance that – to have the idea that you are in danger and you should not lose the fear.

Syrian refugee family just landed after reaching, on a rubber boat from Turkey, the village of Skala Sykaminias located on the northeastern Greek island of Lesbos, on October 9, 2015.

What motivates you to go out and take these images?

The romantic idea that the photographer has to get evidence and try to spread information about what is going on. Let’s take Syria: imagine five years of war without a photographer or camera. That’s the evidence that explains what’s going on. If there is one person who sees my images in Syria and discovers what is happening there, I think I’ve done my job well.

October 8, 2013 – Kawergosk refugee camp is one of the biggest camps in the Kurdish area of Northern Iraq.

The Dream is currently being exhibited at the Bronx Documentary Center from 10 – 27th March: https://bronxdoc.org/