Leah Sobsey is an artist and educator with a background in both art and anthropology, merging these two seemingly diverse fields within her beautiful images of anthropological collections from the collections of natural history museums. Her vividly coloured images are both detailed and beautiful, possessing radiant lighting and striking imagery, so the pictures look more like artworks than studies in nature.

Sobsey works primarily in 19th century photographic processes combined with digital technology. She has exhibited nationally in galleries, museums and public spaces, and her work is held in private and public collections across the USA.

In 2008 she was given a residency at the Grand Canyon National Park, and used the time photographing their museum’s collection of bird, bone and animal specimens. Her first monograph, called Collections, features the resulting work from the Grand Canyon’s collection and will be released this July by Daylight Books. We spoke to her to find out more about the inspiration and processes behind the work.

Bleached bones

Can you tell us a little about the work that you do as a photographer and anthropologist?

I work at the intersection of 19th century photographic processes and 21st century digital technology.

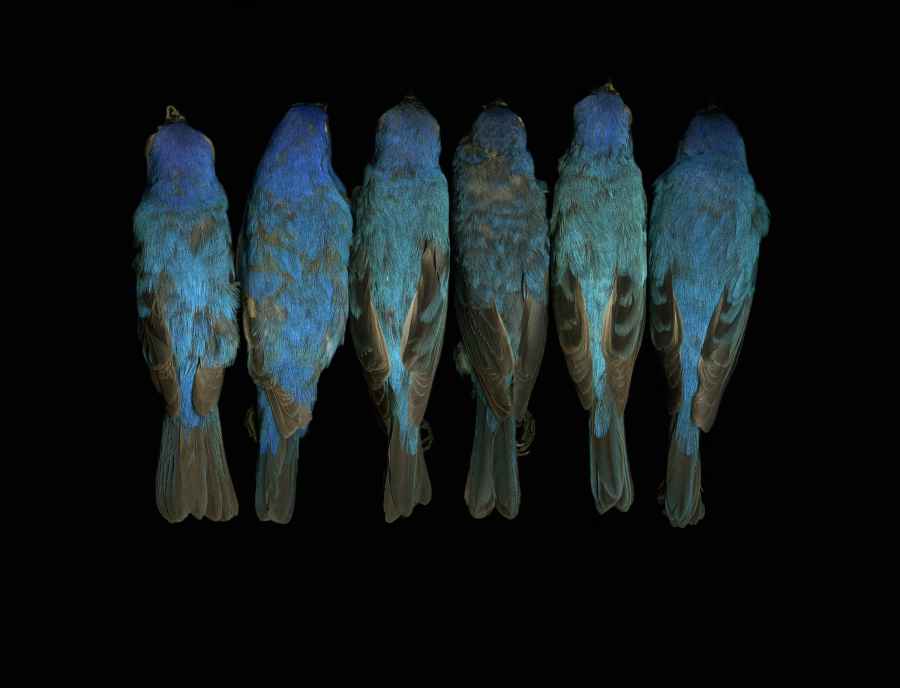

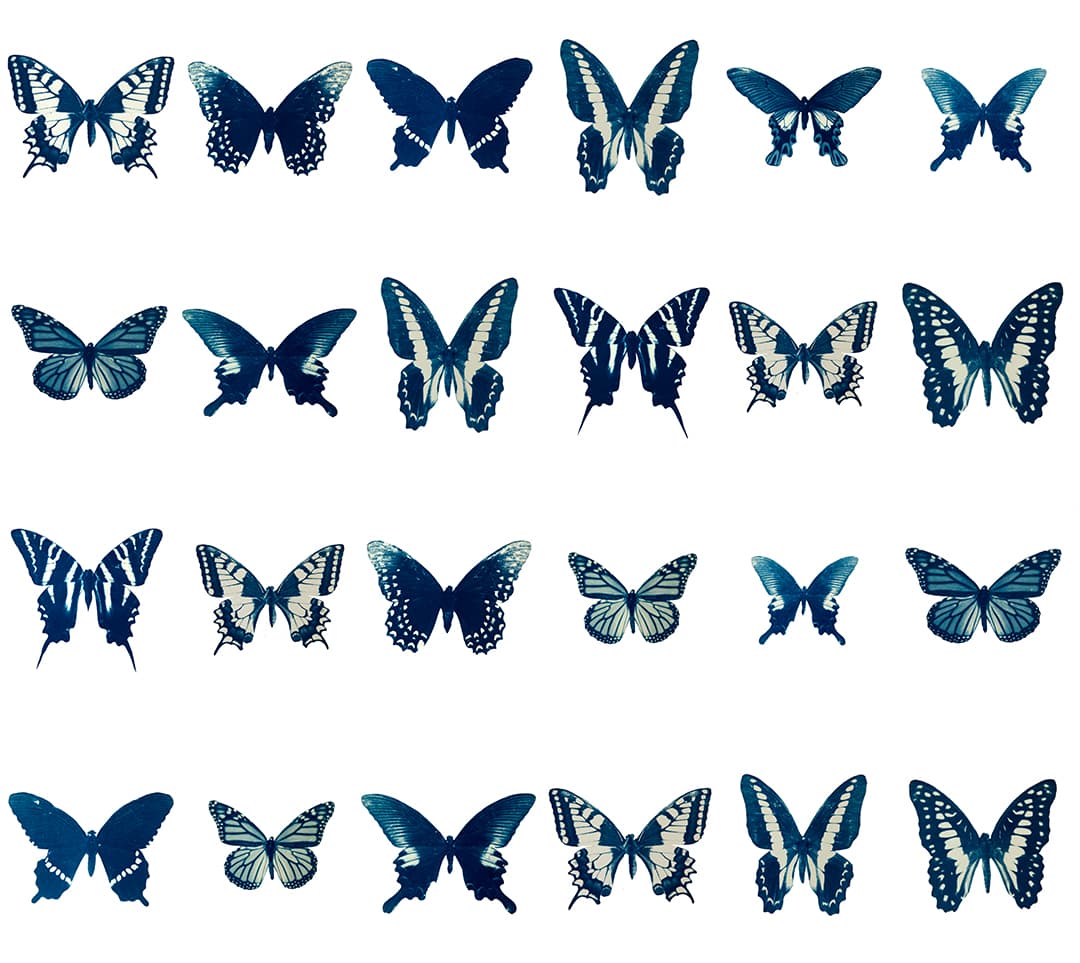

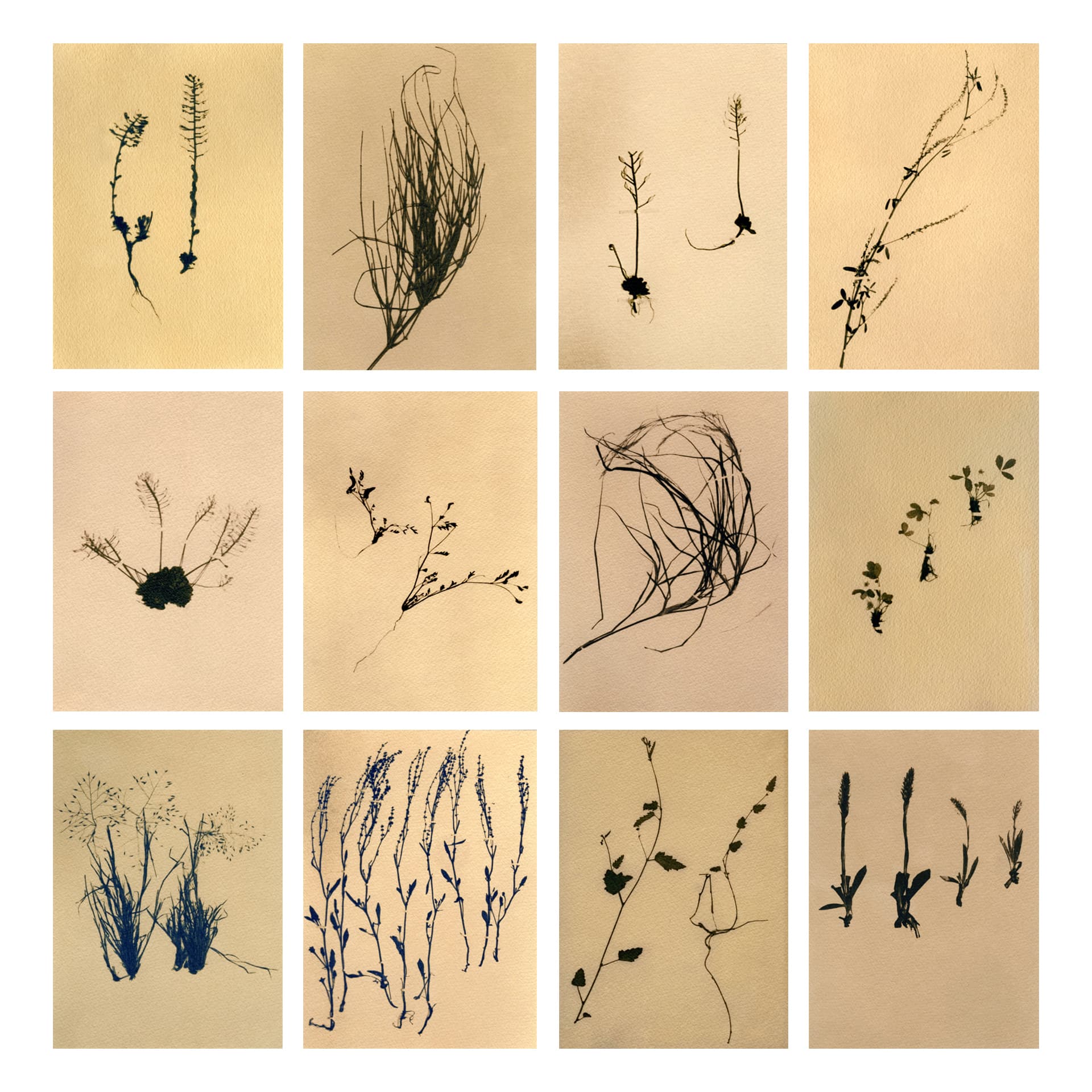

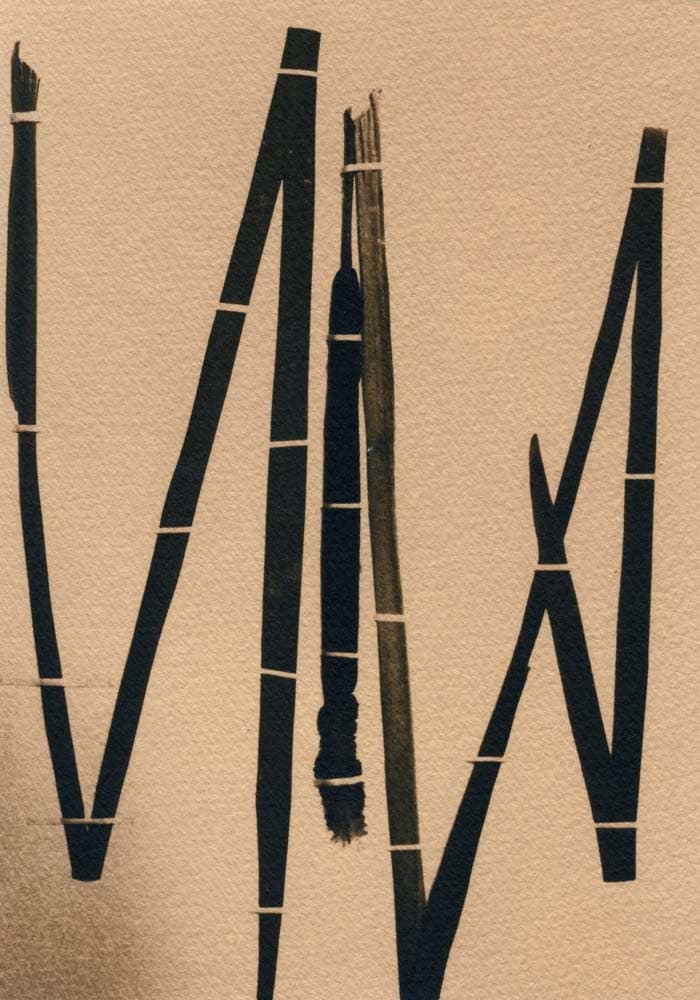

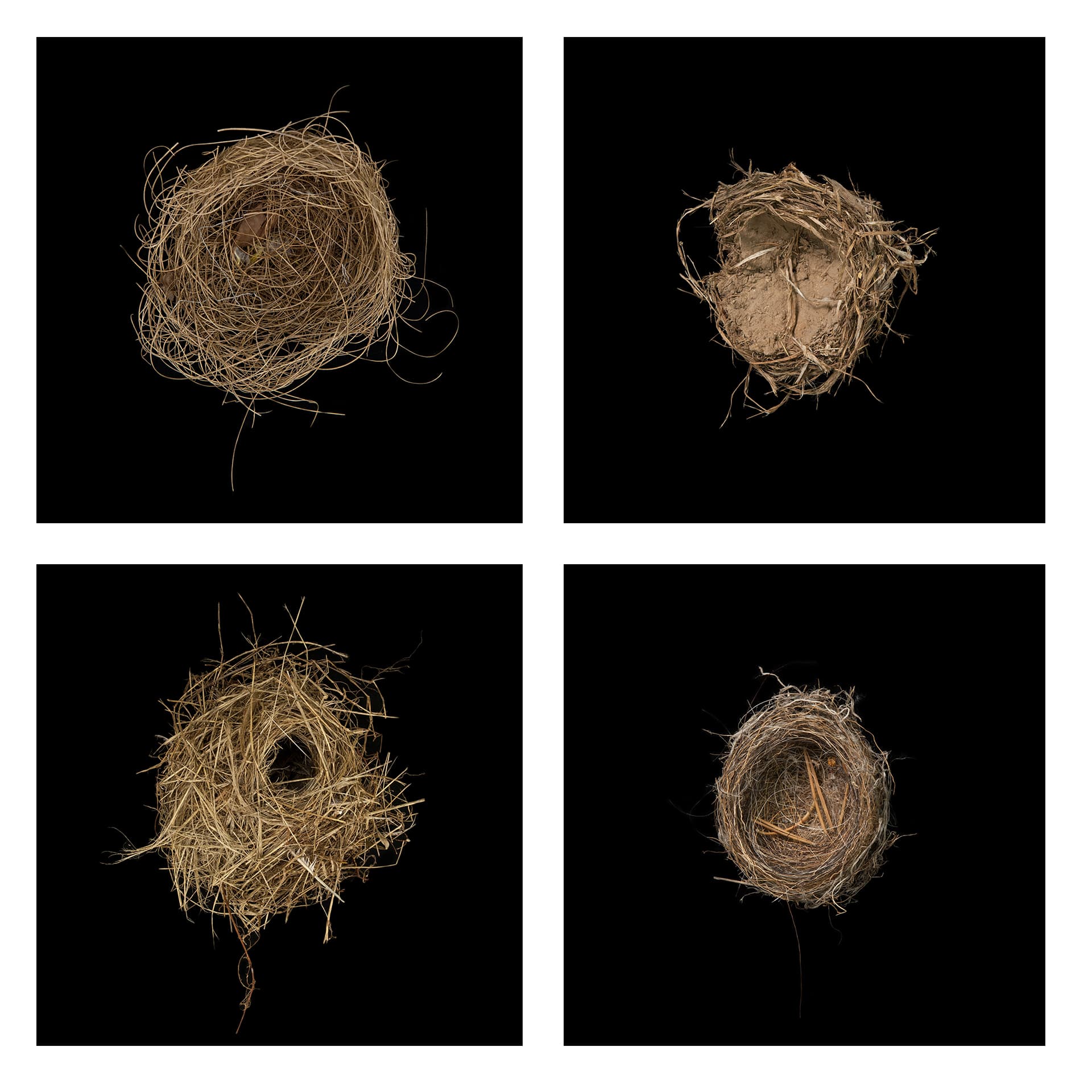

I photograph bird skins, bleached bones, tattered shoes, flora and fauna, and fragile butterflies that I unearth from the dark drawers of national park museum collections across the United States.

The project spans over a decade, which began at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences.

Shoes

The subjects you photograph are specimens from national park museum collections in America, but what made you want to focus on this type of photography in particular?

It was a series of moments over my lifetime that brought me to this project.

I can remember when I was about eight years old, I watched my uncle (who was then the curator of birds at The field Museum in Chicago) open the wooden drawers of the collection – floor-to-ceiling drawers, in my childhood memory. And there were birds. Thousands and thousands of birds – vertical, in endless rows. Bird specimens from across the world. It was beautiful and it was jarring. And it left an indelible imprint.

Fast-forward over two and a half decades: A tufted titmouse crashed into my kitchen window. My first instinct was to hold it; my second was to photograph it. It triggered memories from the Field Museum, launching me into the work of Collections.

I started at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, where I was granted permission to photograph some of the 10,000 bird skins in its collection.

Birds

Your book Collections features specimens from the Grand Canyon National Park. How did you gain access to these collections?

The United States has more than 50 artist-in-residence programmes at different national parks across the country. In May 2008 I was awarded a residency at the Grand Canyon.

Residency lodging was in the 100-year-old Verkamp family home that looks out directly over the canyon.

I knew I didn’t have anything to add to the canyon landscape photography, so I set out to work in the museum collection where they generously granted me full access.

Artefacts

Your images combine 19th century photographic processes with digital technology. Can you tell us about your process and why you chose these methods?

I was first drawn to the herbarium collection that is over 100 years old. Inspired by Anna Atkins, the 19th century botanist and photographer, I decided to create cyanotypes from some of my photographs.

The apartment had no darkroom, so I crawled through the living-room window onto the rooftop where, under the light and heat of the desert sun, I exposed digital negatives on hand-coated watercolour paper in contact frames.

Plucked from their context and illuminated by sun and light, the specimens are brought to life once again. The subject matter of each series is dictated by my discoveries, bridging past to present, honouring both the specimens I work with and the medium of photography.

I don’t always consider myself a documentary photographer because traditionally, context would be provided. Instead, I have stripped the photographs of their context, illuminating them on a stark black background, memorialising them, and creating an ambiguous narrative.

It’s looking at them as hauntingly beautiful objects. It’s looking at them as part of the cycle of life and death, and our place in it. However, the documentarian in me feels compelled to include the scientific name as the title of each specimen and as a way to honour their history.

Butterflies

What were your aims for the project? What were you hoping to capture or convey?

Standing at the edge of the canyon, overwhelmed by the magnitude of the landscape, it’s easy to miss the details.

The museum collections allowed me to hold, rearrange, photograph and memorialise the objects that are part of American history – from mid-19th century tattered shoes in Acadia National Park, and flora and fauna in the Grand Canyon, to an alligator skull more recently found in the Florida Everglades.

This project is particularly timely during this centennial year of the National Park Service, and as museum collections are presently in a state of crisis due to diminishing funding and support.

My current focus on national parks is a way of preserving these fragile specimens that represent American history. This comes at a time when climate change and funding allocations threaten indigenous species and artefacts with extinction.

Flora and fauna

Do you have any plans for future projects?

I have a number of exhibitions that I’m currently working on, and projects that I’m dreaming up.

I will be exhibiting work from Collections at 21C Museum in Durham, North Carolina and Rayko Photo Center in San Francisco, California. Then, I’d love to dig into the archives at the Natural History Museum in London.

Nests

Leah’s book Collections, will be released in July of 2016 by Daylight Books. You can buy the book, or find out more information at www.leahsobsey.com