Steve Fairclough speaks to legendary sports photographer Gerry Cranham about his long and pioneering career

You might not have heard of him but the name Gerry Cranham transcends photography, let alone sports photography. He was only the second photographer, behind the legendary Henri Cartier-Bresson, to have an exhibition at the prestigious Victoria & Albert Museum in London – this was way back in 1971, when even the idea of photography exhibitions was in its infancy.

The pictorial fruits of his lengthy career are now available in the new book This Sporting Life, which was produced thanks to a successful Kickstarter campaign set up and driven by his fellow sports photographer, Mark Leech, and the graphic designer, Doug Cheeseman.

Born in 1929 Gerry Cranham, who’s now almost 93 years old, was a true pioneer of sports photography. He helped to move the goalposts in sports photography from images that merely documented events to pictures that turned the sports photography genre into an art form. His use of remote cameras in the 1960s, deployment of zoom/blur techniques and his approach to underwater photography of swimming produced images that are now considered the norm but were truly groundbreaking at the time.

In fact, Cranham, who was weighted down and working submerged at the time, had to be pulled out of a pool by his hair when photographing the ‘Falkirk Flyer’, swimmer Bobby McGregor, in 1964 to prevent him from drowning. As a result of pushing the envelope technically and artistically, his iconic sporting images have become etched on the public consciousness.

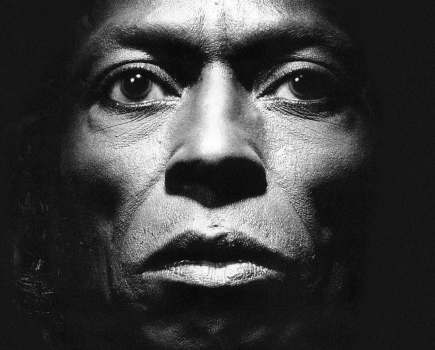

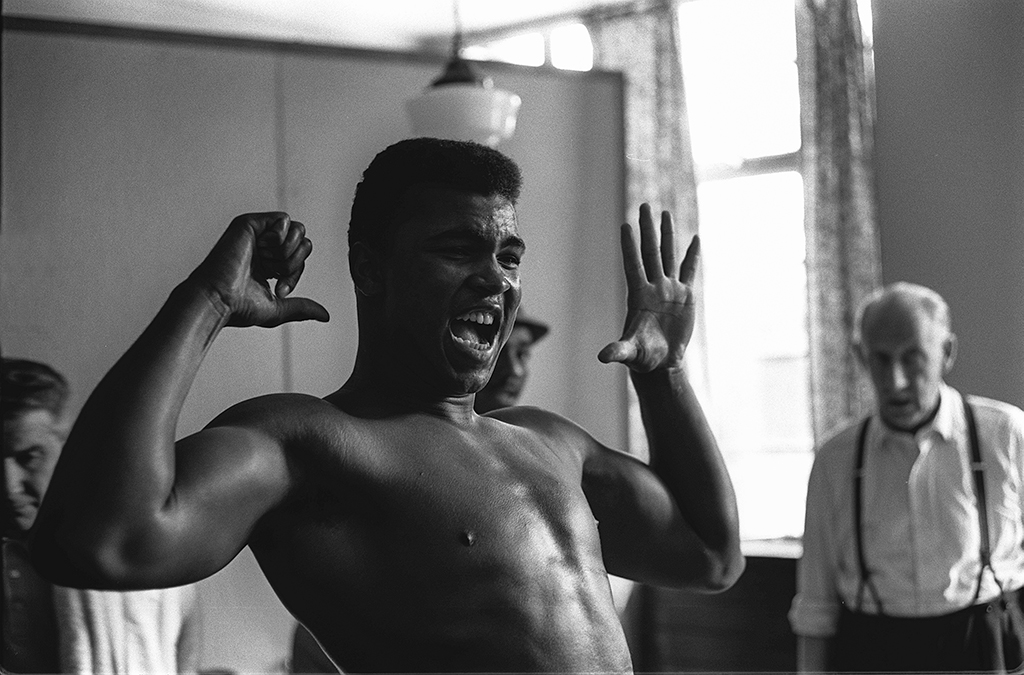

Many of them depict sporting legends such as Muhammad Ali, Arnold Palmer, Olga Korbut, Billie Jean King, Graham Hill, Mary Peters, Pelé, Bobby Moore and the three-time Grand National winning racehorse, Red Rum.

Olympic torchbearer

Cranham’s career as a sports photographer started by chance when a promising middle-distance athletics career was cut short by injury. He had spent five years in the British Army, with the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, and was a competent athlete – he was even a torchbearer for a leg of the Olympic Torch relay in the build-up to the 1948 Olympics in London. However, with his injury halting a potential career in athletics he had to seek a different path and Cranham chose to coach athletes.

As part of his methodology for coaching he began to photograph athletes to use them as a pictorial aid to show their failings; a technique that’s now used by sports and athletes at all levels. He didn’t pick up his first professional camera until he was 27, which is incredible given the vast volume and diversity of his sports photography archive, and explains, ‘I started coaching athletes and I thought it would be a good idea to get a camera to show someone how badly they were running. I had to save to afford the camera. It was a Corfield Periflex, which was about £40, a lot of money then. I didn’t realise how expensive photography was.’

Although his photographic knowledge was fairly basic this didn’t prevent Cranham’s budding photography career from becoming an instant success. He recalls, ‘I had a guide – a little plastic card – with all the exposures, and it was trial and error. But I managed to sell the first roll of film that I took… I was never an amateur [photographer]. There was this road relay from London to Brighton.

A man from the local athletics club had a sports car, and I photographed the race all the way through. From that roll of film I sold most of those pictures. I think they were very bad.’ At that time athletics was very popular in the UK, after Roger Bannister broke the four-minute mile mark in 1954, and soon Cranham’s photos were being sold to Athletics Weekly, which provided a great introduction to the sports photography industry.

Spurs’ goalkeeper John Hollowbread at White Hart Lane, London, 4 January 1964. Shot using a remote camera operated via a cable

Kitchen darkroom

After managing to sell his images, Cranham felt encouraged to further develop his passion for photography. He admits, ‘The stuff I used to sell from my first jobs was terrible, but there wasn’t the competition there is now. I went through hundreds of rolls of film. I had a great advantage, having been an athlete for quite a number of years, so I was able to exploit that.

It meant I knew when to take shots and when to keep out of the way. I found out a little bit more about developing and printing. I bought a cheap enlarger, blacked out the kitchen in my little flat and put my camera lens in my enlarger. Everything was done on a shoestring and was all trial and error.’

In the first three years of his career Cranham only shot athletics but he still had a few hurdles to overcome. ‘Bit by bit, I managed to get into the agency Fox Photos. The problem was I couldn’t get proper access to the photographers’ areas at sporting events, as you had to be a member of the National Union of Journalists. Much of the time I had to shoot from the crowd and other places. But I got to know one or two people.

18 May 1969, Monte Carlo, Monaco. Graham Hill (GBR) after winning the Monaco Grand Prix for the fifth time

I used to supply the local magazines and papers. I met a sports writer, John Rodda, who became The Guardian’s athletics correspondent. He introduced me to a lot of other journalists and they helped me a great deal.’

When Sports Illustrated picked up one of Cranham’s photographs he got to know one of their sports writers, John Lovesey, the magazine’s London correspondent. ‘John Lovesey had worked with a lot of the best American photographers and guided me. He became the managing editor for sport for The Sunday Times. John was a pioneer, as I was.

A lot of the trends in sports photography now come from those early days. The chance to work for Sports Illustrated, the world’s best sports magazine, with its circulation of one million issues a week, and seeing the work and the standards in the magazine, improved me beyond measure.’

Cranham worked closely with Lovesey – they were once invited by Muhammad Ali to take pictures of the boxing icon when he was drinking tea at the Savoy Hotel in London. He also often hit the road alongside the legendary sports writer Hugh McIlvanney to shoot for the Observer Magazine and was friendly with the US photographer Mark Kauffman, who shot for Life and was instrumental in setting up Sports Illustrated.

Cranham’s talent took him all over the world covering huge sporting events – he shot all the FIFA World Cup tournaments from 1966 onwards, the Wimbledon tennis championships and Formula 1 Grand Prix for publications on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean.

Discovering remote cameras

In November 1963 Cranham was in the USA when President John F Kennedy was assassinated. He recalls, ‘I went over to the Sports Illustrated office in America, and while I was there, Kennedy was shot; and being the only English photographer out there I eventually ended up in the White House when LBJ was declared President! A few days later I was at the Boston Celtics basketball match, and a colleague said “Do you want to have one of these new remotes?” which only the Americans were using. I picked it up on the hoof.’

He brought the kit back to England and used it in the net for the first time during a January 1964 Tottenham v Chelsea FA Cup tie. His fellow photographers teased him and the crowd in the Paxton Road end threw peanuts at him but this produced a mould-breaking image for football coverage, which showed the Tottenham goalkeeper John Hollowbread jumping in the air at a foggy White Hart Lane.

Cranham was one of only two photographers to shoot the legendary 1966 FIFA World Cup Final between England and West Germany using colour film – he estimates he shot 28 rolls to cover the historic event. He had been shooting in colour since 1963 and explains, ‘I met this chap who worked for Walt Disney. He was a journalist and, at the weekend, he made his money covering sports events for the Sunday papers. He said to me, “Gerry, colour is the future. You should be shooting colour.”

Of course, it was mainly black & white then, it was rare that anyone shot colour, particularly in sports photography. I was inspired by the Time/LIFE way of doing things, creating picture essays in colour. I was one of the first to shoot a lot in colour over here [in the UK], and it helped me get ahead. I was using Ektachrome – it was only something like 60 ASA but by then (1966) I was reasonably proficient in colour but it was difficult as the film speed was very slow.’

As well as his penchant for shooting in colour Cranham’s intuitive and unique way of shooting revolutionised sports photography. Many of the techniques that we see today can be credited to Cranham, most notably the zoom/blur. In a highly competitive and expensive industry, he simply had to stand out, ‘I had to do something different because I had five kids to feed at home!’ Much like fellow sports photography great Neil Leifer, Cranham stood out because his techniques and angles meant ‘no one was doing’ what he was doing.

He concentrated on framing and composition at a time when everything was captured using manual focusing, but he also had the eye and brains to add context by choosing to photograph the spectators and their surroundings as much as the athletes. Of his famous 1971 exhibition in the V&A Museum, Cranham recalls, ‘I was so busy with advertising and sport… this chap kept ringing me up and I’d say, “Give me a ring another time.”

This went on for months. Eventually I said, “You’d better come down and have lunch with me.” He turned out to be the deputy director of the V&A. Photography had taken off a bit then and in 1968 the V&A had a Cartier-Bresson exhibition. My exhibition was the next one. I was the first British photographer to have an exhibition there.’

Shepherds Bush, London, 30 May 1963. Heavyweight boxer Cassius Clay trains before his fight with Henry Cooper

Munich and Montreal

Although his career spanned from 1957 right through to 2013, Cranham only covered two Olympic Games – in Munich in 1972 and in Montreal in 1976. He explains, ‘It was tough. It was working on the outside and never getting in the middle. Being told where you were [going to shoot] and that was it. At least in Munich you could move around a bit, and make the best of a bad job, but in Montreal it all went security mad.

Sports Illustrated was paying people to queue up overnight to get the best [shooting] spots and it just went to ridiculous levels of trying to fight and get into the best positions. If you wanted to move, because something was blocking your view, it was terribly restrictive. I didn’t enjoy Montreal at all. It put me off and I never shot another Olympics.’

He continues, ‘Munich was so exciting and had a wonderful atmosphere. I didn’t mind being stuck on the last bend instead of at the finishing line. As a former middle-distance runner I knew this was where the race often develops. I got some shots of (5,000 and 10,000 metres Olympic champion) Lasse Virén overtaking there. Being on the corner gave me a nicer shape and a nice position for relay changes – it just worked for me.’

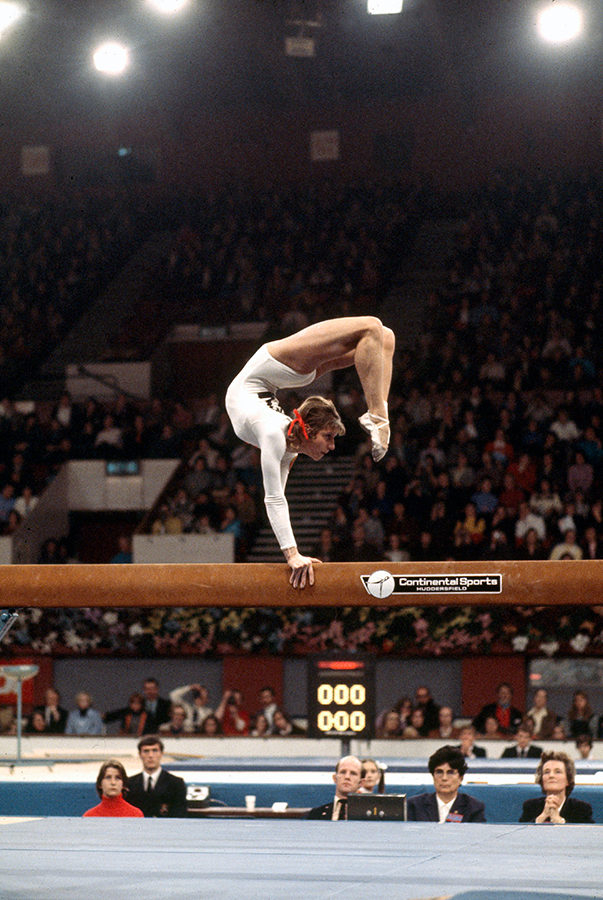

His famous images of the USSR’s star gymnast Olga Korbut at Munich 1972 remain iconic and he reveals, ‘I wasn’t shooting up to the mat [at the gymnastics]. I didn’t know about Olga Korbut beforehand – she just appeared and it was just unexpected. I spent a bit more time at the gymnastics than I’d planned. In 1972 it was pretty cool [working at an Olympics] but by 1976 it was just all queuing and it was madness.’

Picking key moments

Cranham used a range of cameras during his career, including Nikon Fs and Leicas, but when he retired he had no need for them. He reveals, ‘When I was finished with them, they were only good for the scrapheap. It took me five years to master focusing, exposure and composition. In the days of automated digital cameras, we’ve forgotten exactly what it was like for sports photographers shooting film.

There was a lot more thought and physical actions required to get shots you wanted. It’s not like pushing buttons with autofocus. You had to get the exposure right, the film wasn’t very fast and you had to focus. I was shooting 35mm film and, all the time, I was concentrating on keeping the cameras loaded, not shooting too much, and picking my moments.’

He concludes, ‘In my day everything was done a lot more thoroughly, there was a lot more time. I used to have to lug all this gear around; I worked with four cameras and a big bag of lenses. Now my back is really bad; I’ve had two lots of major surgery, and can hardly walk! But I was very lucky, I met the right people, and I took note of what they said. It’s very pleasing to see my pictures still around and know that they haven’t gone forever.’

Gerry Cranham

Born in 1929, Gerry Cranham is a British photographer, who is widely regarded as the one of the world’s foremost practitioners in sports photography. He began his photography career in 1957 and worked right through to 2013. He worked with many newspapers and magazines such as The Watch, Sports Illustrated, Time and The Evening Standard and his work is in the collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum.

The Gerry Cranham book This Sporting Life, by Mark Leech, Doug Cheeseman and Charlotte Wilson, is published by Offside Press in association with Vision Sports Publishing (ISBN 978-1-913412-29-6) with an RRP of £40. https://shop.visionsp.co.uk/products/this-sporting-life-standard-edition