Fireflies have become endangered species. They are beetles and use light to attract a mate and warn off predators – sadly the recent use of pesticides is killing off the river snails on which they feed. Credit: Tim Flach

The saiga, a nomadic antelope whose range extends from Kazakhstan to Uzbekistan, is a curious-looking creature. A survivor from the ice ages, its drooping nose can warm up cold air (essential for bitter winters) while filtering out dust (for dry summers).

“The saiga looks like something out of the canteen scene in Star Wars,” laughs photographer Tim Flach as he recalls his brief encounter with the animal. Tim may be laughing now but this goat-like creature proved extremely tricky to photograph.

“These animals have been decimated through hunting for their horns,” he reveals.

Only the males grow horns, which are sold in East Asia for their supposed medicinal properties. In 2015 a deadly virus hit the population and this, combined with poaching, has caused numbers to plummet. As a result, the saiga are now a critically endangered species – and are extremely hard to find.

With the help of a contact in Moscow, Tim located a saiga herd – but it was just the beginning of his troubles.

“I visited an area near the Caspian Sea during the summer and found myself in a fly-infested location,” he recalls. “By 9.30am the heat was so fierce that it distorted the air and my pictures were blurred.”

Not to be deterred, Tim returned during the winter months when temperatures fell to -35°C. Against all odds, this time he got his picture.

“Poachers hunt the saiga on a kind of moped, so when they hear a motor, or any kind of noise, they just run and run,” he explains.

“I photographed one saiga as he was glancing back but by the time I took another shot, he was gone.”

The saiga has been hunted for its meat and horns for centuries, but a deadly virus in 2015 and 2016 killed thousands. Credit: Tim Flach

Eye-opening

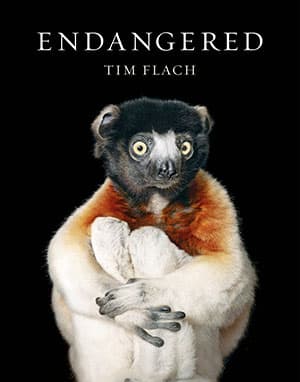

More than two years in the making, Endangered, Tim’s latest book, is eye-opening in every sense. Who knew that vultures play such a crucial role in disease prevention, for example?

“Vultures are nature’s cleaners,” says Tim. “They live off the dead and they clean the carcasses. Now 90% of them have disappeared and it’s having different consequences in different continents.”

He explains that in India, for example, cases of rabies have increased as dogs have filled the gap left by the birds’ rapid decline. Unlike vultures, their digestive systems cannot destroy dangerous pathogens and consequently they pass them on to humans.

Deciding which endangered species to feature in his book resulted in some interesting conversations.

“I asked a lot of eminent people which animals I should include but the world’s panda expert is just going to say ‘pandas’!” he laughs.

Continues below…

[collection name=”small”]

Nevertheless, he spent six months asking leading scientists and conservationists questions about value systems and nature. One of them was Dr Jonathan Baillie, chief scientist at the National Geographic Society.

“Jonathan has been at the coalface, educating people about conservation,” says Tim. “Like many conservationists he is concerned about how traditional wildlife photography can create action. There is a difference between what we know and what we act upon.”

Jonathan wrote the excellent prologue and epilogue to Tim’s new book.

When the weather turns, polar bears make a pit in the snow and hunker down, allowing the snow to drift over them. Credit: Tim Flach

Telling stories

In the end Tim decided to look for stories, rather than follow any prescribed ‘endangered species’ list. The vultures are a perfect example.

“Instead of going after the glamorous animals everyone else chases in the Maasai Mara I chased vultures, because their story is so important,” he explains.

Another obvious candidate of endangered species was the ploughshare tortoise. Highly prized by poachers due to their glorious shells, these land-based reptiles only live in Baly Bay in Madagascar and take 15 years to reach their breeding age. As a consequence, the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust goes to great lengths to protect them. It might seem drastic but defacing their shells seems to be the most effective way to deter poachers. With this in mind, Tim photographed ploughshare tortoises both with and without their man-made engravings.

To deter poachers the shell of the ploughshare tortoise is intentionally defaced. Credit: Tim Flach

The endangered species of western lowland gorilla was another must-have subject for the book. Habitat loss and illegal hunting are the main threats here but what’s less well known is the role these gorillas play in the tropical forest ecosystem. They have a fruit-based diet and disperse seeds via their droppings. Once again, Tim was after the story but this time he got more than he bargained for.

“There was a military clampdown during my visit,” he recalls. “Law and order broke down, so it was a struggle to get home. The planes wouldn’t pick us up because the pilots were scared. They didn’t behave in a particularly honourable way and left us in Gabon. I had a wonderful experience watching the gorillas but then it comes back to humans again.”

Tim did get home eventually but the experience left its mark.

Like most images in his book, the lowland gorillas were photographed with a Canon EOS 5DS.

“It’s got a 50MP sensor and is amazingly good at catching high-speed action,” enthuses Tim.

To prove his point he draws my attention to an incredible picture of a lowland gorilla scooping a handful of water to its mouth. The water has created a reflective coating on the gorilla’s knuckles and you can see the forest canopy on the surface of its dark skin.

“This picture was taken handheld from a boat,” explains Tim.

Makara was the first Indian gharial to be captive-bred outside of his native range. He hatched in Florida in 2016. Credit: Tim Flach

Familiar faces

If you’re familiar with Tim’s work, you might recognise a few pictures in Endangered – the shots of Celebes crested macaques, for example are taken from his ‘More Than Human’ series. He makes no apologies for the repetition.

“There are 20 images in the book that I borrowed from my other projects, partly because it seemed crazy to go back and redo them, but also because I knew I could rework the files,” he explains.”Photographers evolve and we know how to manage things differently, so we can take a file and start again from scratch.”

There are familiar settings, too. The pictures of military macaws were shot in Tim’s studio, for example. But there were also countless times when he was forced outside his comfort zone. On one such occasion he dived to a depth of 35 metres in the sea off the Galapagos Islands with a school of hammerhead sharks circling high above him.

In the wake of the 1989 ban on trading elephant ivory, poachers have switched their attention to the magnificent canines of hippos. Credit: Tim Flach

“I’m not an underwater photographer and I’ve never pretended to be but for my own integrity I needed to cover every aspect,” he says. “Oceans make up the majority of the surface area of the planet, so I couldn’t just ignore them!”

So, having photographed endangered species from a single cave-dwelling olm to a swarm of migrating monarch butterflies, I wonder how Tim feels about the state of the planet and our role as its custodians.

“I feel that I could, perhaps, be useful,” he explains. “I hope the book brings stories that touch people emotionally and make them better placed to know how to move forward. Our most valued treasure is the world we are in and if we are not careful, we are going to spoil our nest and lose the most valuable thing we have.”

Endangered by Tim Flach is published by Abrams (ISBN 978-1-41972- 651-4) and features more than 180 images documenting the lives of endangered species.

Tim Flach studied fine art at St Martin’s College of Art and Design. He emerged with a fascination for photography that has led to numerous commissions, awards, solo exhibitions and a presence in permanent collections around the world. Endangered is his fourth and most ambitious book to date. To find out more visit www.timflach.com.