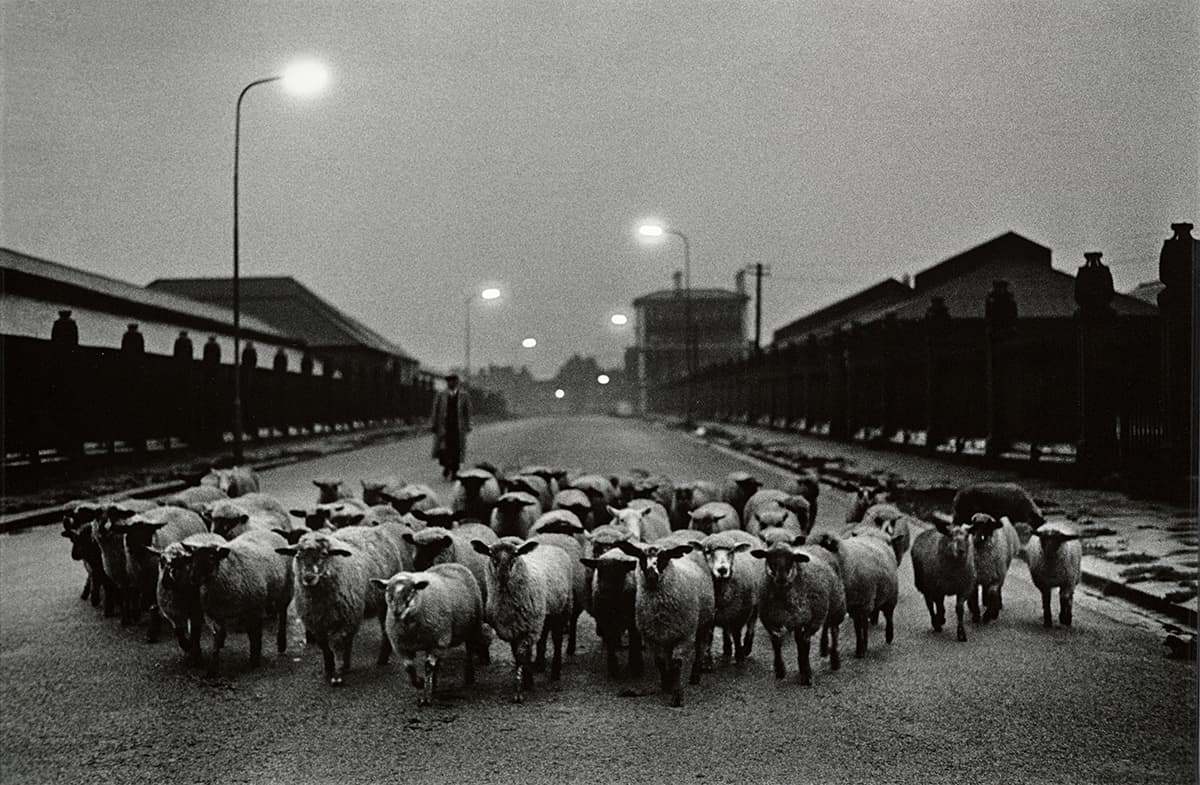

Sheep going to the Slaughter, Early Morning, near the Caledonian Road, London, 1965

Photographing conflict has become an all- too-familiar staple of photography. It’s a genre that began with Roger Fenton who documented the Crimean War back in 1855 and went on to feature people such as Robert Capa, one of the greatest war photographers of our time, who was killed in Vietnam in 1954 after stepping on a landmine while reporting on the First Indochina War.

While the methods of warfare may change, war is a constant in human civilisation, and for decades photographers have risked their lives to bring the truth to the world. Don McCullin, who was born into a working-class family in north London in 1935, has spent the past six decades visiting some of the most dangerous places in the world.

A Palestinian woman returning to the ruins of her house, Sabra, Beirut, 1982

Don celebrated his 80th birthday last year, which was commemorated by an updated version of the retrospective photobook, simply called Don McCullin; a new version of his autobiography, Unreasonable Behaviour; and a limited-edition collection of his images, called Irreconcilable Truths. McCullin will also be exhibiting work at Photo London from 19-22 May and the Arles photography festival in France from 4 July-28 August. It’s been a hectic few months.

‘I never had an interest in photography,’ says McCullin. ‘I was in the Royal Air Force and I came out with a very nice camera, a Rolleicord, which was inappropriate for doing reportage. Someone had encouraged me to buy it. I was stationed in Nairobi, Kenya, and someone there said, “Why don’t you buy this Rolleicord? It will only cost you 30 quid. It’s brand-spanking new and comes in a beautiful case.” So I bought this camera and I went around Nairobi with it for a couple of days and took a couple of pictures. Looking back, they were really amateurish shots. I then went from Nairobi to Cyprus, then came back and put the camera in a chest of drawers. I never had any interest in it after that because I returned to the environment I left before my military service started.’

McCullin put the camera into a pawn shop, but it wasn’t long before he reclaimed it because his mother was concerned that he would fall into bad company if he didn’t have something to occupy himself. Ironically, it was the fact that he mixed with slightly unsavoury people that gave him his first break in photography, he remembers.

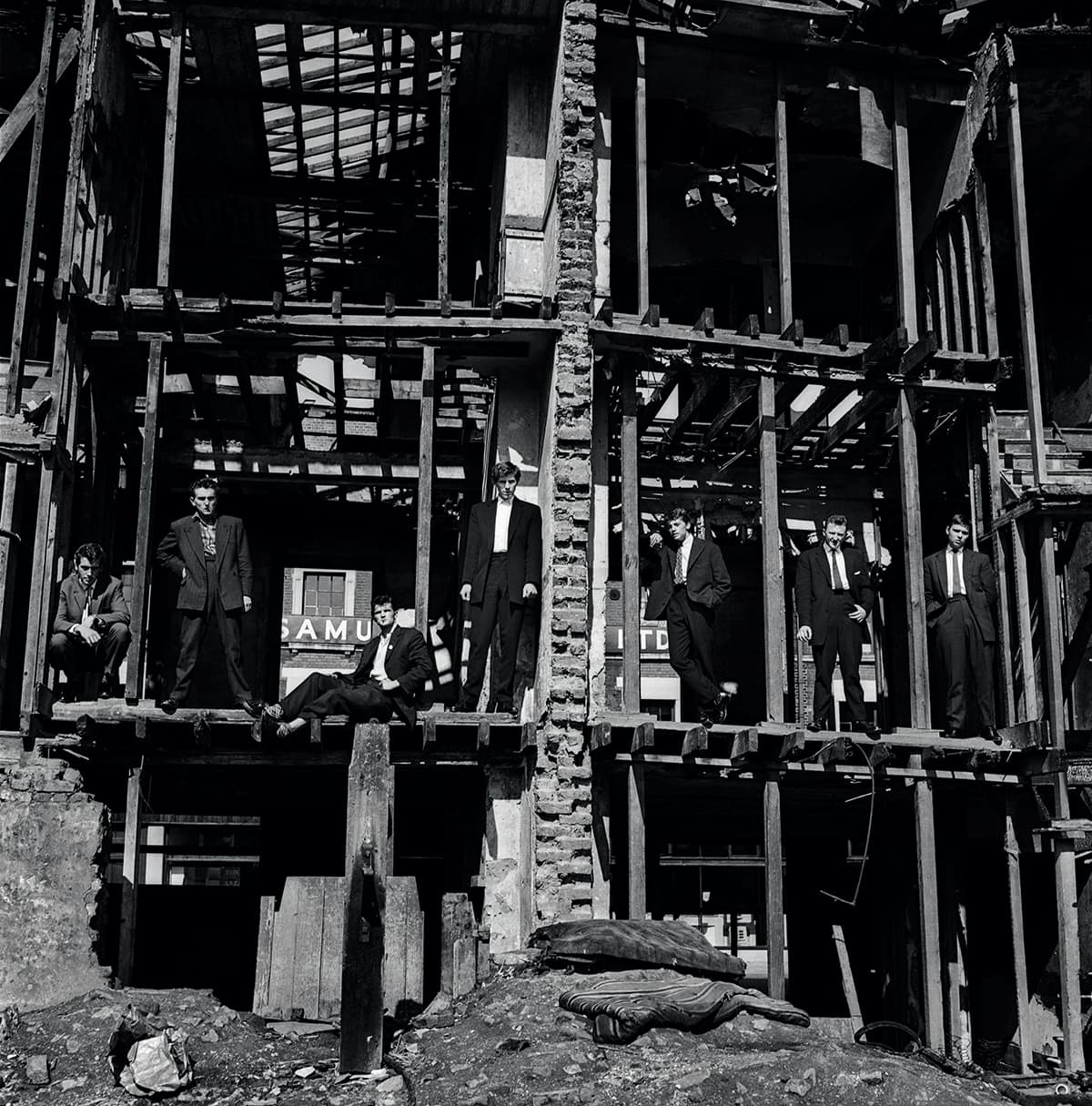

‘The boys I grew up with got involved with something quite violent – the murder of a policeman,’ says McCullin. ‘They didn’t do it, the other crowd did. During the build-up to the trial, they said, “Why don’t you go and get that camera and take some pictures of us”. They knew this was going to be in the newspapers and they were showing off. I took one picture of them in a derelict building, which is at the bottom of my street where I grew up.

The Guvnors in their Sunday Suits, Finsbury Park, London, 1958

‘I was working in Mayfair, in London, at the time in an animation studio. I was given my job back after national service, as a sort of messenger boy. Then they said, “Now you’ve worked in a darkroom, would you take over our darkroom?” They did line drawings, so I had to photograph the drawings, use the enlarger and work in the darkroom. I processed the film of the boys in that darkroom and I still have the negative to this day. It’s probably one of the best negatives I’ve got. I had no exposure meter, so I guessed the exposure. I even remember it was taken on an Ilford FP3, which was a very slow but a very fine film.

‘The people in the place where I was working – a very posh place in London’s Berkeley Square – saw the picture and they said, “Why don’t you take this picture to The Observer?” So I did, and they asked me to take some more pictures for them, which they published.’

The following Monday, McCullin was contacted by various companies and offered jobs in TV, on newspapers and magazines. ‘But I wasn’t really a photographer,’ he says. ‘It was a pure fluke that I composed this picture and it

was quite dramatic.’

Monochrome world

The language of reportage photography is nearly always composed in black & white, with its best exponents utilising monochrome. McCullin eschews colour in his work for a very deliberate reason. ‘I think colour takes you on another journey,’ he explains. ‘With me, I’ve always been a black & white photographer.

I was forced to do colour when I eventually found myself working on The Sunday Times, so colour became a necessity. But even so, I used to persuade the art director there to let me shoot black & white and they would put my mono images on a four-colour printing press. Black & white is bleak and stark, and it brings reality into things, whereas colour gives you opportunities to go off at different thoughts and places.’

Friedrichstrasse, Berlin, 1961

McCullin’s work has a very distinctive style, thanks to carving his own niche. ‘With reportage, you had to be on the street and you had to have your feet in the mud,’ he says. ‘It’s not a case of being protected by a knowledgeable photographer and you have the comfort and safety and warmth of that.’ He does, however, admit that his career wouldn’t have taken off without the input of other people in the same profession.

‘While there was some influence of other photographers, I still very much had my own identity,’ says McCullin. ‘When you work for someone like, say, Bailey and Irving Penn, you were stifled by their fearful reputation and tantrums. I have made my own journey in life. I wasn’t relying upon other people. On the other hand, I couldn’t have made that journey without acknowledging the work of other people.’

Perhaps surprisingly, the photographer who influenced McCullin the most wasn’t a war photographer, but someone who specialised in a different field entirely. ‘I studied the work of Alfred Stieglitz, who for me was much more important than Capa,’ says McCullin. ‘Covering wars is easy if you’ve got the b***s to do it, because it happens in front of you. You don’t have to compose or create, whereas somebody like Alfred Stieglitz was a very intellectual, very creative, sophisticated person in his own right, and he dictated on many occasions where he thought photography was most important.’

US Soldiers tormenting a civilian in the old city of Hue during the offensive, Tet, Hue, 1968

Fractured parameters

Perhaps because he came from a different background to many of his contemporaries, McCullin had no problem breaking the rules and conventions of the industry. ‘They are meant to be broken,’ he says. ‘In the late 1960s I went to a Commonwealth Prime Ministers’ Conference, and in those days the Fleet Street photographers all lined up to take photos. I ran out in front of them with my 35mm camera and they shouted: “Oi! You can’t do that! Get back here! What the Hell do you think you’re doing?” They also said: “Do you think you’re going to get anything with that stupid little camera?” They were all using Rolleiflexes and I had a 35mm Pentax at the time. So they were making fun of me, thinking I wouldn’t get anything with such a “horrible little camera”. People like Henri Cartier-Bresson went around the world with a 35mm Leica and took the greatest pictures in the world, so why would I listen to fools like that? So I did break the rules.’

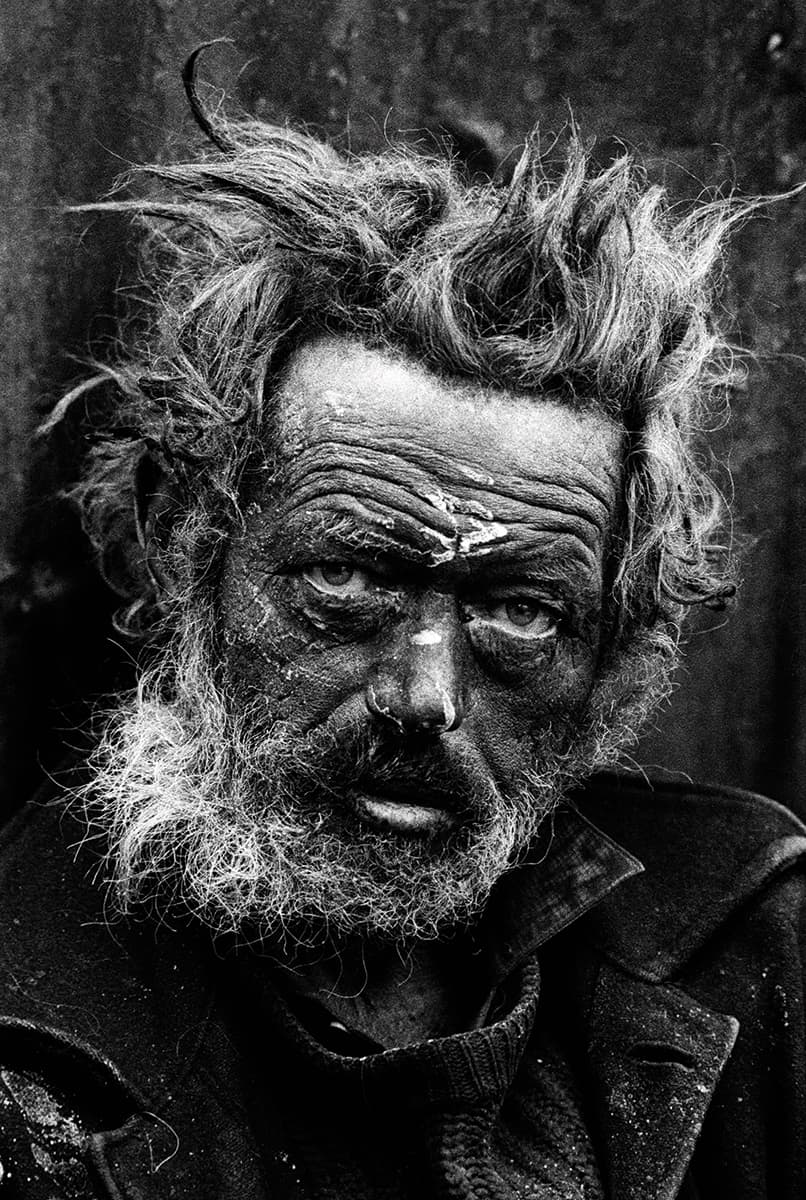

Tormented, Homeless Irishman, Spitalfields, London, 1969

McCullin still develops film, but decades of working in a darkroom have taken their toll. ‘I am not going to be doing it for much longer,’ he says. ‘I have passed my 80th birthday and I am not going to be standing in that darkroom. I have been doing that for 60 years and am beginning to get chest wheezes and pains. Doing that for 60 years, I might as well have been smoking three packs of fags a day. Developing fluid is lethal stuff.’

He does use digital cameras, but he still has a preference for film. ‘I have been given some digital cameras, and it has just taken me a while to understand them. They are far too sophisticated for anybody,’ he says.

McCullin is best known as a war photographer, and he has seen some of the worst acts humanity has carried out over the years. ‘You can’t divorce yourself from tragedy like that,’ he says. ‘It’s impossible. If you do, you shouldn’t be doing it. How it affects me is that I get less and less patient with things and people. I have realised that – particularly now – what affects me is doing what I am doing now, talking about it. I am so tired of talking about it because I have been doing it for so long.’

Over the past few decades, McCullin has switched his emphasis to landscapes, a subject that seems a world apart from his war photography. But the former Londoner, who has lived in Somerset for three decades, gets a great deal out of documenting the land.

Dew Pond by Iron Age Fort Somerset

‘I started [landscape photography] before I came to live in Somerset,’ explains McCullin. ‘I used to live in Hertfordshire and took two nice pictures: one of a dead sparrow in the snow, and one of my village at dusk and you can hardly see it. I was enthusiastic about not settling and pointing my camera at one thing.

‘You should not be governed by rules, which I think should be broken. I had such a wide canvas that I looked at the sky, and I looked at the landscape, and I started forming a kind of love affair with the wintrous landscape of England. I am not interested in the summer because it comes too close to a chocolate-box image. It’s even worse now because if you take a digital camera and do an autumn shot, it’s so sickly. The colours are totally false, they’re not real colours from digital cameras.’

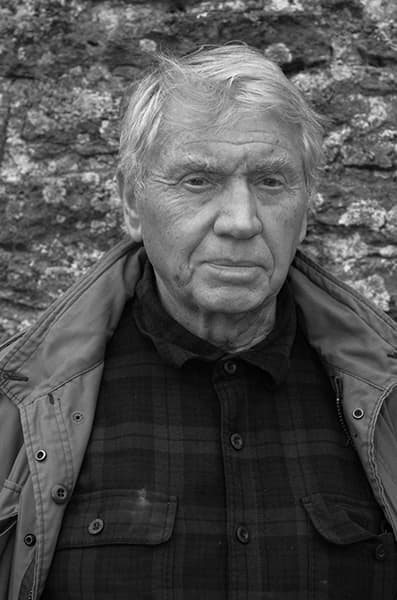

Don McCullin CBE, Hon FRPS, is a British photographer whose images of warfare and social hardship have been widely seen and published throughout the world. He has also recently produced a series of landscape images.

Don McCullin headshot by Joel Meadows