Long overlooked in the UK, Charlie Phillip’s pioneering documentary work is now enjoying the attention it deserves. Jon Devo talks to him.

When Charlie left his home in Jamaica and arrived in London as a boy, he came with a strong sense of Britishness, instilled in him by his parents and his school education. This was true of many African and Caribbean people whose families answered the call from the ‘Mother Country’ to travel to Britain and help rebuild the country in the wake of the Second World War.

‘I arrived on 18 August 1956 at Paddington Station. And my father came to meet me. Before I came he told me that an English suit was a Burton suit, Bata shoes and a Poplin shirt,’ Charlie tells me. He agreed to meet me at The Tabernacle, a local cultural centre, just a few roads away from the place he first lived when he came to London. I know The Tabernacle well. I’ve been going there since I was a boy as I also grew up in the same area as Charlie.

Outside the Piss House Pub, 1968

The Tabernacle is a Grade II listed building that became a community arts centre in the 70s. As you walk in, photographs of local people throughout the past six decades adorn almost every wall. Charlie’s photography is among the collection and when he walks in, he’s greeted by a stream of people. He no longer lives in west London, but he’s still clearly a local celebrity and a much-loved figure.

‘We lived at number 9 Blenheim Crescent, and we had to share a room with two strangers, in what they called a double room. It was a refuge point for a lot of people who came here and didn’t have anywhere to stay at first,’ he says.

Man on Westbourne Park Tube Station, 1967

‘Many others settled in Birmingham, Wolverhampton and Reading. I’m trying to get a blue plaque put up at number 9, because as far as I’m concerned it is part of our history and part of this area, which has now been forgotten about. But I documented it, so I’m glad that after 60 years now, those images have come to use [as evidence]. The photograph never lies.’

Charlie believes that the current generation of young British people seem more keen than ever to learn more about the full picture of British history. This is partly why he feels that his work is getting more acknowledgement today than it ever has in England before.

‘We’re coming up to the seventh generation of African-Caribbean British people living in the UK. And when I was a child, you couldn’t ask your parents anything about those times. And in the 50s/60s there’s a missing gap within our history, because our parents didn’t talk to us directly about what was happening. Much of our history is otherwise orally shared, because not so much was written down then. This is where I came in. When I first started taking photographs I planned to put them in an album and share them back home. Our family only intended to stay five years.’

Despite going for many years without ever catching a big break, Charlie is enjoying this new-found interest in his work. ‘I’m grateful to see that 50 years later I’ve got volunteers and others around me who are saying: “Uncle Charlie, we’ve got to tell your story because we still haven’t been given a proper platform to tell our story.” Even if it’s only a small part, it’s still a part of British history and until recently, a lot of that story has been left out. This is why I don’t celebrate Black History Month.

‘Our history is British History, whether some people like it or not, from the moment we were colonised. It’s about time the institutions see us from a new perspective. We do have history here, we do have culture, we do have a story.’

Notting Hill Couple, 1967

As a boy, Charlie tells me, he never wanted to become a photographer. He had a deep passion for all things maritime and actually set his sights on a career in ship design and construction. Back in Jamaica, before he ever set sail for the UK, Charlie would spend time at the docks, watching the ships arriving and departing for England. His second passion was for opera music.

‘I wanted to be an opera singer,’ Charlie tells me. ‘I remember my employment officer at school asking me what I wanted to do when I was older. When I told them I wanted to be an opera singer, he told me I was having a f*#ing laugh and suggested I aim for a job in transport or the health service. That’s as far as it goes. We were never expected to do anything that we aspired to do, outside of those types of boxes.’

Throughout Charlie’s career, he’s experienced varying degrees of disbelief from galleries, publications and agencies. Some were sceptical that he, a black man, could be the person behind the brilliant photos he captured. While others outright refused to believe the provenance of his work until he produced the negatives to prove himself. Even then, Charlie felt that some grudgingly acknowledged his ability. Interestingly, Charlie says he found the most acceptance and recognition during those first few decades when living and working in Europe.

Despite his work being displayed around the world, Charlie has only gained recognition as a key figure in British photography over the past few years.

Silchester Road before and after demolition of the area, 1967

A Journey into Photography

In some way, you could say that photography found Charlie. His eye for imagery was often sparked by artists outside of the photographic field. One of his favourite early images was Norman Rockwell’s classic painting ‘The Runaway’, which he discovered while flicking through a copy of Esquire magazine. Fashion and art magazines were often left at his home by American GIs that his father befriended. Charlie took up photography as a hobby using a box camera that could take eight 6×9 pictures on a roll of 120 film. Rather than taking up an apprenticeship, he decided to teach himself how to capture and develop his own photos. Charlie saved up money from his paper round to buy a magazine titled Do It Yourself Photography from Boots chemist for 3 shillings and sixpence, which would be roughly £15 in today’s money accounting for inflation.

One day, one of his father’s GI friends was too inebriated to return home after one of the family’s famed weekend house parties, so he had to stay over. In the morning, he had no money to get back to his base, so Charlie’s father loaned him some money and he left his Kodak Retinette 35mm film camera as insurance. But the gentleman never returned to collect it, so Charlie inherited it and put it to good use documenting everything from his local community, to student protests in Paris, 1968, to anti-war and anti-apartheid protests throughout the 60s and 70s.

He eventually moved on from the Kodak Retinette and acquired a Petri camera, which he bought second-hand for £25.99. Then when he began travelling into Europe, he upgraded to the Nikkormat FT, the more affordable cousin of the Nikon F series cameras that accepted the same lenses. And settled on the Leica IIIc when he was living in Rome, where he lived on and off for eight years, working as a mild-mannered paparazzo.

Sharing his thoughts on his favourite lenses and film types over the years, Charlie tells me that affordability was one of the main reasons that much of his work is in black & white.

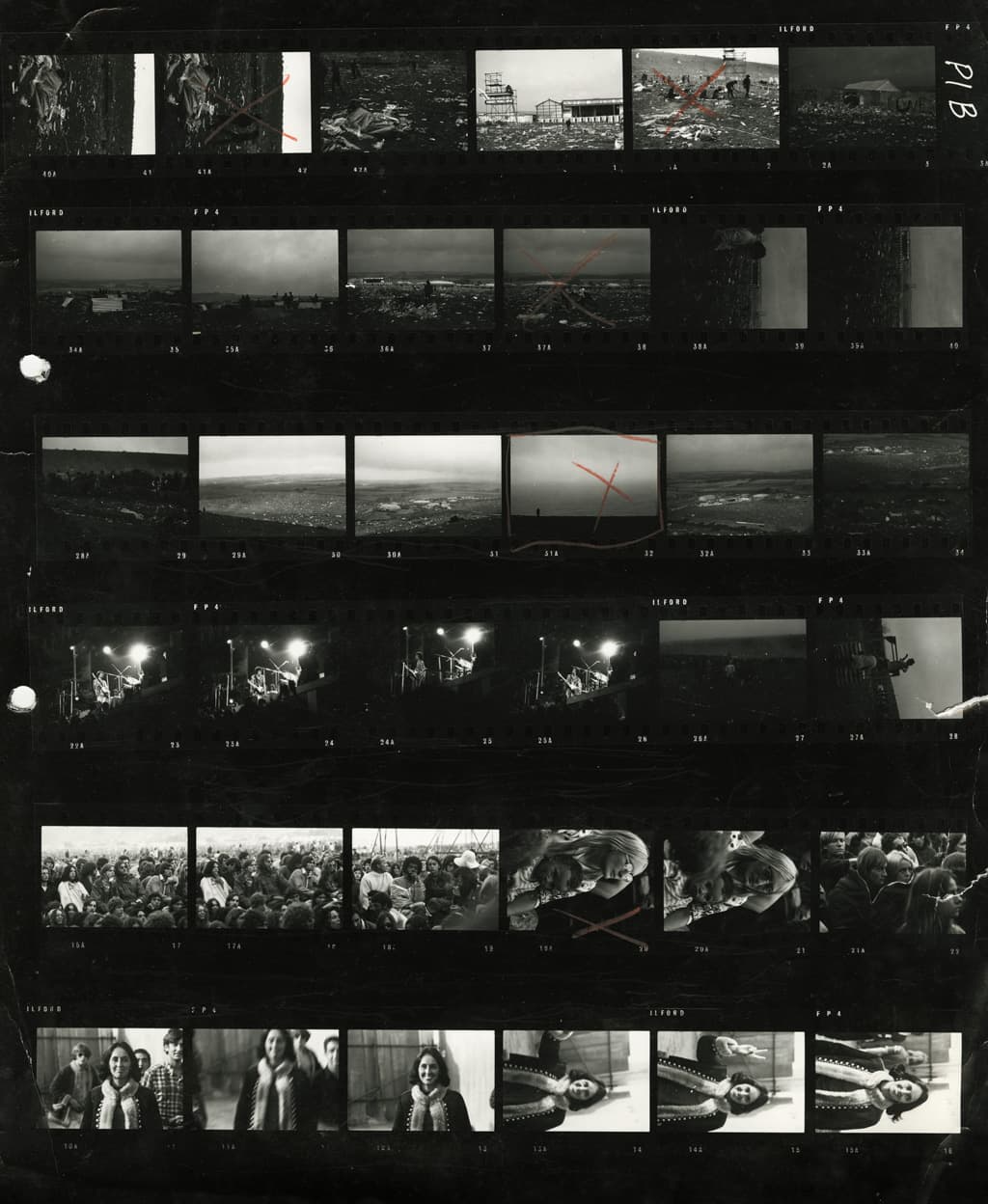

‘I went through different periods. My favourite film was an Ilford FP4 or HP5. Sometimes I would also use the Kodak Tri-X or Plus-X, but I was really an Ilford fan. It was the softness of them. I also used to like the AgfaPhoto APX 35mm film too.

‘As for lenses, the 50mm was standard, but I liked an 85mm too. When I worked with a Leica, I liked the Carl Zeiss Jena Tessar 50mm f/2.8. Sadly, when I came back to England, I had to pawn my Leica for £35.’

Charlie was there to photograph the first ever Notting Hill Carnival in 1966. He was working in his darkroom on Portobello Road and set off into the streets with his camera when he heard the commotion and music. His pictures of the inaugural west London carnival have become iconic as younger generations have come to cherish evidence of these significant cultural events.

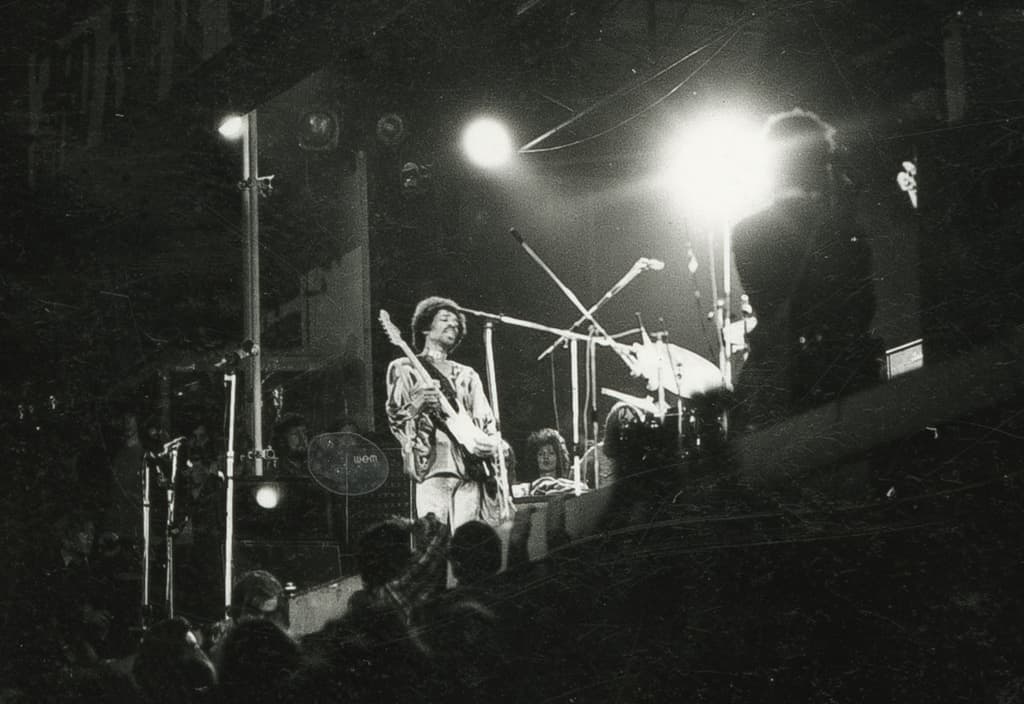

Jimi Hendrix, Isle of Wight Festival, 1970

Exploring Europe

After reading Jack Kerouac’s On The Road Charlie became a beatnik, living in squats and hitchhiking around Europe. ‘As a young man, going through different stages in life, I travelled to France during my revolutionary stage. There was a big student uprising. We went there because we wanted to show solidarity.’

The unrest that Charlie was referring to took place in May 1968, as students staged occupation protests against capitalism, consumerism and imperialism. Arriving at Gare Du Nord, Charlie was greeted by a young man whose head was pouring with blood following clashes with police. It was a startling moment that still lives with him to this day. Haunted by the experience, he left Paris and hitchhiked down through France, stopping off in Marseille, Monte Carlo and Avignon. Eventually, he wound up in Rome.

‘I was hanging out in Rome, staying in a hostel. One morning I saw all these crowds of people. It was Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton [there]. They were promoting Cleopatra and I thought to myself, “I could join in with this”.’

That moment inspired him to become a paparazzi photographer. ‘I was the only black photographer, but they found me curious. I met a lot of people. And it was during the era of the Spaghetti Western, so I started photographing a lot of the B-list American actors and actresses who needed headshots to get more jobs. People like Robert Woods, Henry Silva and Marcello Mastroianni.’

His time in Italy was arguably the height of his photographic career. Charlie was doing well, landing work with a number of publications, including Italian Vogue. And wound up being cast as an extra in Federico Fellini’s 1969 film ‘Satyricon’. He also developed a network of influential friends, including Donyale Luna, who’s widely regarded as the first black supermodel, and renowned photographer Henry Cartier-Bresson.

‘We met at my first major exhibition in Milan. People there used to call me the black Cartier-Bresson, he was a nice guy. Sadly, I lost all of those photographs I had with me and him. Nobody believed me when I came back to England and showed my portfolio.’

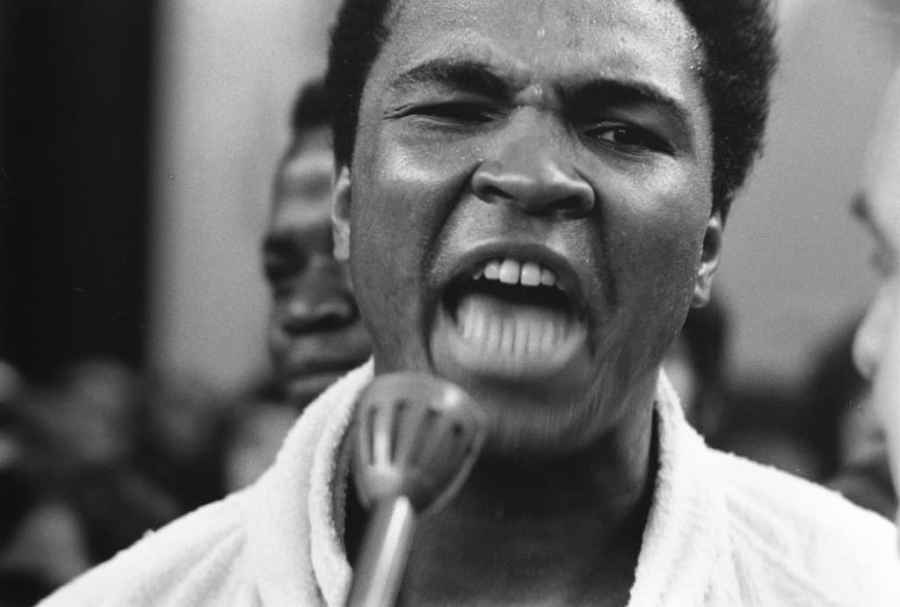

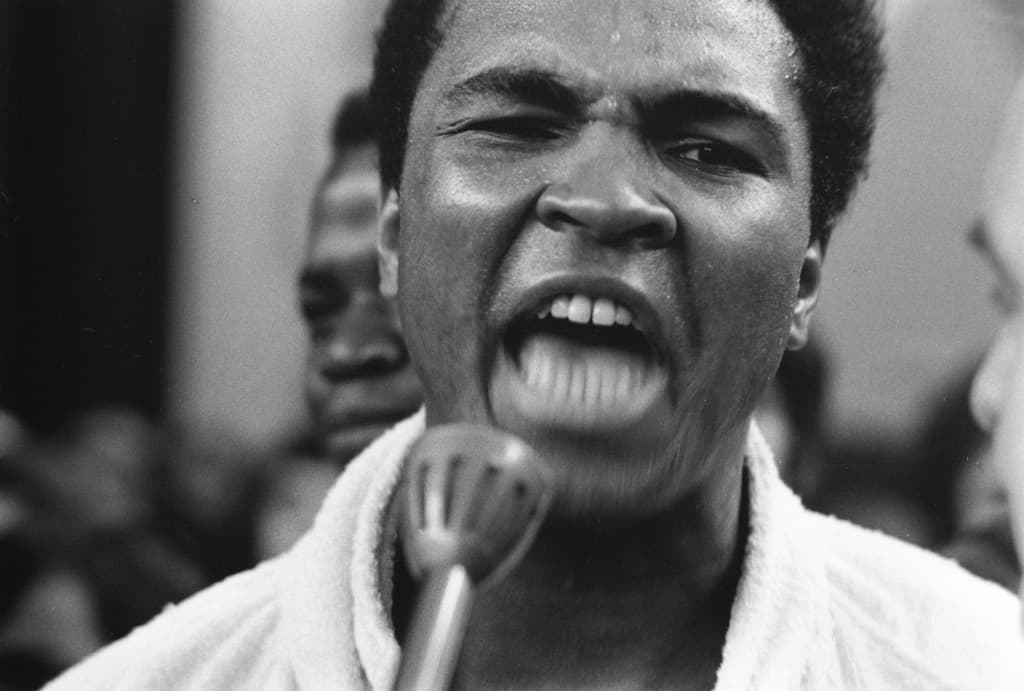

Muhammad Ali, Zurich, 1971

By chance, Charlie also found himself working as the personal photographer for Muhammad Ali. ‘After he lost his title and lost his boxing licence because he didn’t want to go to Vietnam, he had to come to Europe. He was fighting a European champion called Jürgen Blin and I was living in Milan at the time so I travelled up to Switzerland to meet him and photograph him. He was so glad to see me, because I was another brother. I took these series of photographs and I thought I’d make a name for myself with one of them.

At the time, Charlie had been regularly submitting work to Life magazine’s editor in Milan and built up a good relationship with the editor at the time.

‘One of the best magazines that always showed me a lot of respect was Life magazine. Every time I took my stuff into Life, they’d give you a roll of film and say “thank you for coming”. That’s why they’ve got one of the biggest archives. I captured an iconic photograph of Muhammad Ali and I thought “Yeah” that’s my ticket.’

The image Charlie was referring to is an image of a buoyant Ali looking into the camera and his mouth is blurred from the motion. It was an image that said “I’m back!” Charlie tells me and he was hoping it would make the cover of Life magazine. Sadly, it wasn’t to be.

‘Unfortunately, the editor told me that they wanted a colour photograph, so they couldn’t use it.’

Eventually Charlie returned to London, drawn back to the community of his boyhood. The area that fuelled his creativity over so many decades.

‘There have been so many talented people here who think in another dimension. This area’s always been fantastic for diversity and culture. Because you’ve had the Irish here, the Afro-Caribbeans here, you’ve got the Africans here, Eastern Europeans. When you bring people together from all over, you get something fantastic. That’s how you end up with something like Notting Hill Carnival.’

Renewed Exposure

‘I haven’t taken a photograph commercially since 1975. My archive was under my bed and in my loft for the last 40 years. And it’s not until ten years ago that they discovered who I was. And I have this archive telling our side of the story that’s been overlooked. The exposure I get has always been at a grassroots level.’

Despite the hiatus, Charlie’s work continues to be published. His work has recently been featured in a landmark book celebrating the history of Notting Hill Carnival. His work documenting 50 years of African and Caribbean funerals in London has also been collated and published in a book titled How Great Thou Art.

‘I’ve been taking pictures of funerals for the past 50 years. Funerals are just about the fact that someone has died, but it’s a celebration of their life. The beauty about Afro-Caribbean funerals is that celebration. You can see it in the dress codes, for example. If you look through the book, each service has a strong theme. This is evident throughout each funeral over those decades. Fashion plays a big part too. It used to be the case that people would wear all black, but over time it’s gotten more colourful. Now it’s common for people to wear the favourite colours of the person who died. The whole point is to celebrate life. It’s part of our culture and history as well, that is why I’m documenting it.

Clinton at Cassidy’s funeral, Kensal Rise, 1972. Cassidy was a mechanic and he loved Land Rover cars. His dying wish was that he go to his funeral in a Land Rover rather than the traditional hearse

‘Early on, the main song that would be sung at a service was the classic hymn How Great Thou Art,’ Charlie says, before treating me to a quick rendition of the chorus. This is where the book takes its name from. He then tells me that the musical choices have evolved to include pop classics like Tina Turner’s (Simply) The Best and Sinatra’s My Way.

Charlie explained that this unique collection of images wasn’t curated by a picture editor or art director, but rather by ordinary people of various ages. Before the work was first exhibited, Charlie’s team conducted surveys with his local community to gauge which type of photographs they’d love to see published in the final book. Charlie is keen to appeal to younger generations, which informed his decision to open up the selection process to the people he wanted his art to engage with, rather than so-called ‘experts’. The book’s cover features the funeral car of a west London mechanic, whose coffin was placed on the back of a Land Rover. Charlie was keen to point out that this was long before the Duke of Edinburgh’s impressive hearse alternative was ever revealed.

Looking over his work, I was surprised to learn that the name Charlie Phillips was not highly regarded within the British art and photography worlds decades ago. Particularly because I grew up in the same area that Charlie settled in when he came to the UK. Notting Hill is now one of the most famous and recognisable locations in the world, popularised in cinema by films such as Bedknobs and Broomsticks, the Paddington Bear movie franchise, Love Actually and Notting Hill starring Hugh Grant and Julia Roberts. But when Charlie arrived in the late 50s, it was effectively a slum. Few photographers have documentary evidence of the cultural melting pot that was Notting Hill throughout the second half of the 20th century. Long before it became a desirable haunt and home to celebrities and millionaires.

The lack of recognition for Charlie’s pioneering photography prompts a couple of key questions: Why would such culturally important work go largely unnoticed for so long? And what has changed?

‘It’s by public opinion, my friend! Because the institutions have suppressed my work. I wouldn’t be recognised if I never put on events in this place [local cultural centre The Tabernacle] or in my annual pop-up cinema exhibitions. I’m also grateful for all of the barbershops, garages and hairdressers that gave me wall space. I even put my work up on railings…it’s by public demand that my work is getting the attention that it is today,’ Charlie proclaims.

Isle of Wight Festival, 1970

A team of supporters have encouraged Charlie to keep sharing his work, despite the seemingly uphill struggle for acknowledgement. ‘They say they’ve got to keep my legacy alive because I’ve documented a story that hasn’t been given enough of a platform. I’ve done this through my own will. As I said, we’ve got to tell our side of the story. Although it’s there, I feel there could be a broader scope.’ With his work and career enjoying renewed attention, Charlie is using his platform to tell his story unapologetically. As has been the case throughout his life, Charlie refuses to be confined by any narrow definitions and he continues to forge his own path, with or without the approval or endorsement of the art world establishment.

‘Our story hasn’t been properly told or properly documented. You hear everything from the cultural elites, but I’m doing things on a grassroots level,’ Charlie explains. At last year’s The Photography Show at the Birmingham NEC he revealed some never-before-seen images of Muhammad Ali during his talk. Sadly, due to travelling a lot over the years and film stock not being returned, Charlie has lost a significant portion of his images. But he is still managing to track down images archived by publications that have printed his photographs in the past. The work featured in his TPS presentation will also include one of the earliest photographs that he has saved, which was captured during a Jamaican Independence Day celebration in London, on 6 August 1962.

When he first picked up a camera in 1958, Charlie couldn’t have known the future cultural significance of the images he was to capture over the 50s, 60s and 70s. But we could all learn a lesson from his life’s work and delayed fame. He never took a picture for ‘likes’ or to follow a trend. He didn’t persist as a photographer because it gained him notoriety. When I asked him what he was looking for each time he raised a camera to his eye, Charlie told me that he was simply searching for something real. He’s looking for honesty.

Charlie Phillips’s photo book How Great Thou Art is available to purchase online soon and Lottery Funding has allowed for a group of his supporters to collect and display his work in an online archive: charliephillipsarchive.com.