When there is no foreground object particularly close to the camera, focusing about a third of the way into the scene – in this case, just in front of the second set of posts on the jetty – will give you all the depth of field you need in a landscape

Front-to-back sharpness

One of the most commonly asked questions regarding depth of field is, ‘How do I get front-to-back sharpness?’ The usual advice for beginners is to focus a third of the way into the scene. This is because depth of field extends twice as far behind the point of focus as in front of it.

However, this method lacks precision, as it’s often difficult to exactly locate ‘a third of the way in’ – and it doesn’t take into account variables such as the focal length of the lens you’re using, or the aperture you’ve set. Nonetheless, it can work surprisingly well in many situations.

Where it does fail is when there is an object close to the camera that needs to be kept sharp along with the background. In these cases, a more accurate way of calculating and controlling depth of field is needed – namely, focusing using the hyperfocal distance.

Photographers often assume this is a complicated technique when, in fact, it’s really easy to use. Put simply, the hyperfocal distance is the precise focal distance at which depth of field is maximised for a given aperture and focal-length combination. While it can be tricky getting to grips with the principles, it’s perfectly possible to apply the technique without getting bogged down in the theory.

Hyperfocal distance focusing was used here to ensure sharpness was present all the way through the image

Circle of confusion

For those keen to understand the theory, however, you need to start with the ‘circle of confusion’ (CoC) – and no, it’s not a group of photographers trying to understand hyperfocal distance!

The circle of confusion is the maximum size at which an unsharp ‘blob’ will appear to the human eye as being indistinguishable from a perfectly focused point. For 35mm film or ‘full-frame’ sensors, this is usually stated as 0.030mm, and assumes a maximum print size of about 10x8in (about 8x enlargement for 35mm).

Different formats will require more or less enlargement to achieve the same-sized print, and so different circles of confusion are used. The circle of confusion is part of the equation used to calculate depth of field and hyperfocal distance, so knowing what CoC has been used in the calculation can be useful.

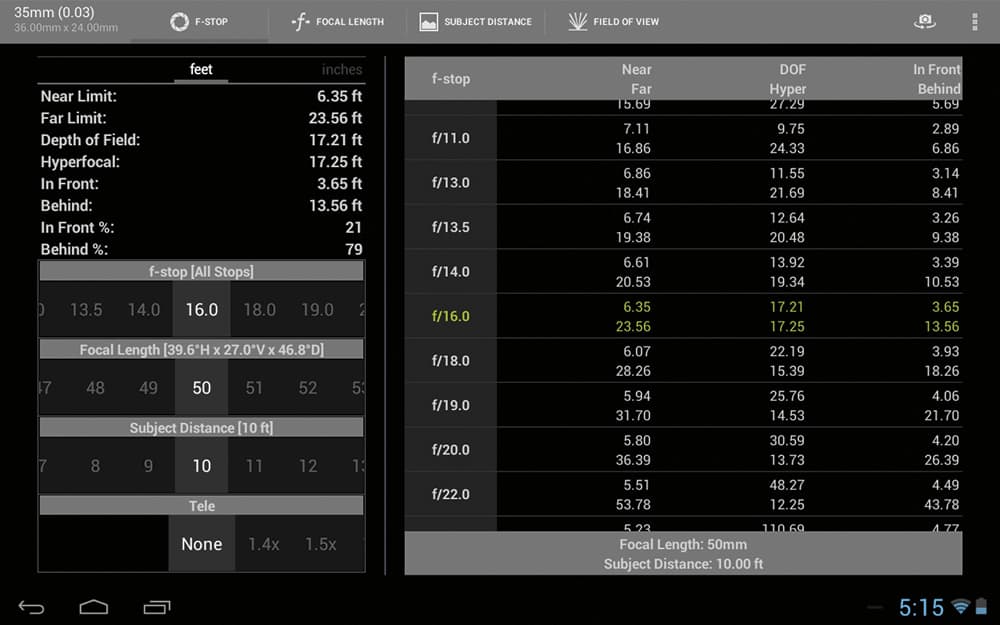

For once, practice is easier than theory, and there’s no need for complex calculations using the CoC, as there are many pre-prepared charts available, as well as several smartphone apps.

Hyperfocal distance chart or app

Unless you really enjoy complicated maths, use a chart or phone app to help you find the hyperfocal distance.

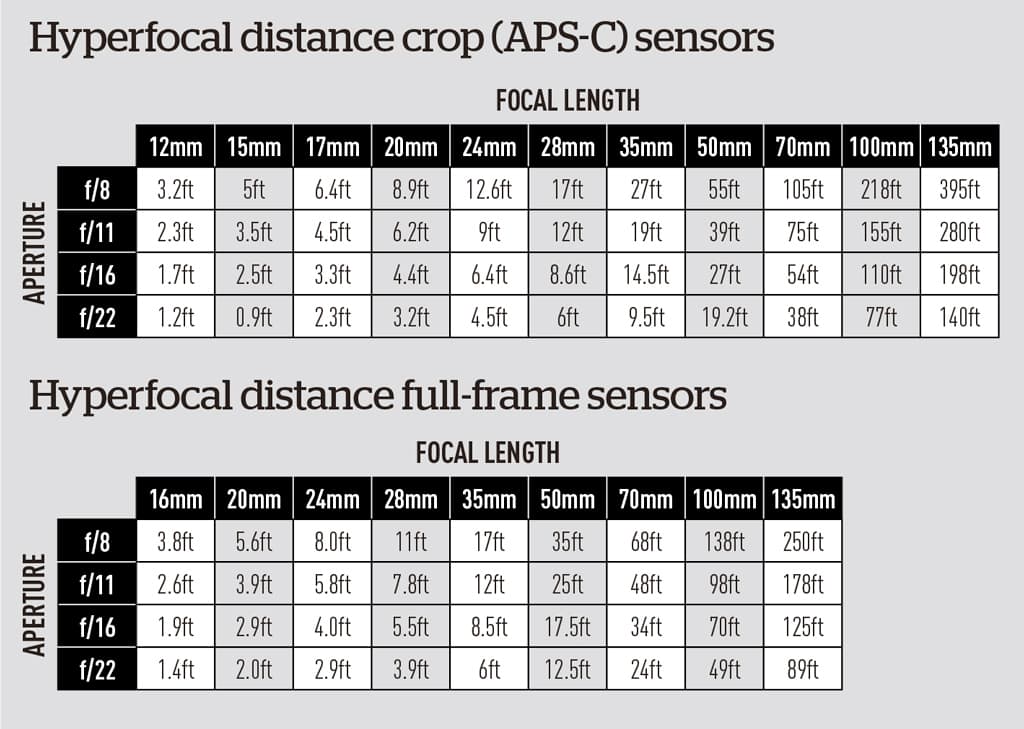

Below are two sample charts. One for crop-sensor (APS-C) DSLRs and the other for full-frame DSLRs, showing hyperfocal distances for popular focal lengths

To put hyperfocal distance into practice, just check the focal length and aperture you’ve set, find the hyperfocal distance from your chart or app and then manually focus on an object at this distance. (You could use the distance scales on your lens, but these are not always very detailed or accurate on modern zooms).

Everything from half the hyperfocal distance to infinity will be within the zone of sharpness. For example, if you shoot with a full-frame camera at f/11 on a 20mm lens and set a hyperfocal distance of 1.2 metres, depth of field will extend from 60cm to infinity.

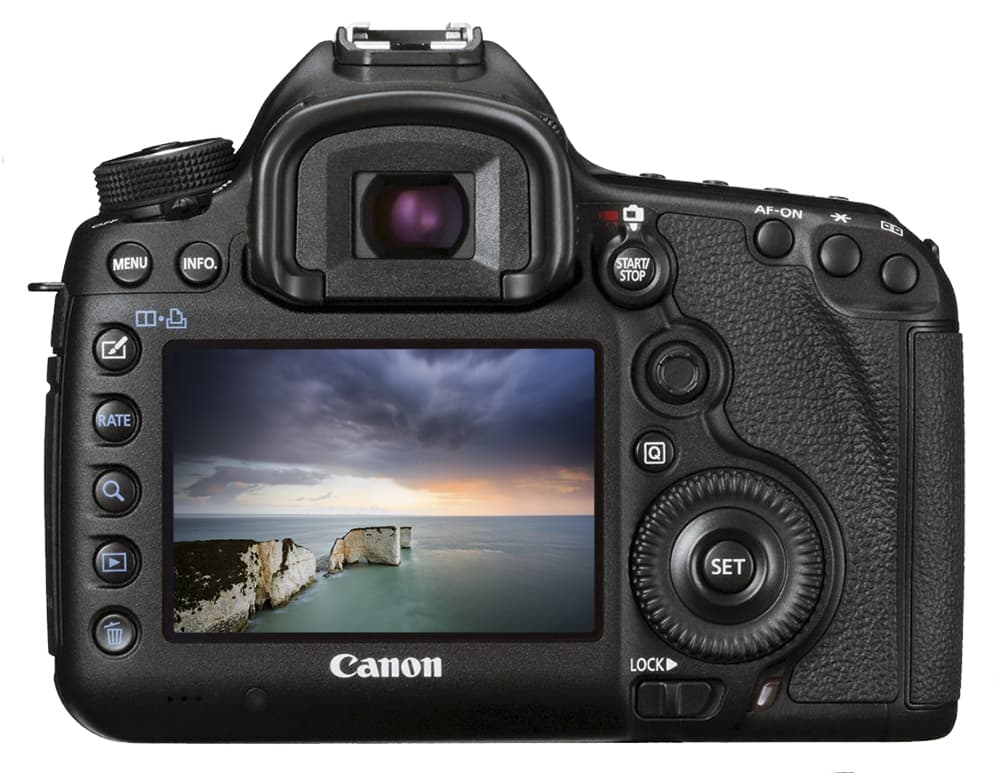

Before pressing the shutter, you’ll need to check that your depth of field calculations are correct. Looking through the viewfinder won’t show you the depth of field, as the aperture stays wide open until the shot is taken. Most cameras have a depth of field preview button, however, which enables you to manually stop the lens down to the shooing aperture. The problem is that with the aperture stopped down, there is less light coming through the lens and the viewfinder image might be too dark to be useful. Live view works better as the screen brightens to compensate for lower light levels.

Camera manufacturers implement live view in different ways, though, so check how yours works. For example, Canon’s live view operates in the same way as the viewfinder, with the aperture wide open. To check depth of field, press the depth of field preview button. With other makes, such as Nikon, the live view image is shown stopped down to the taking aperture, so there is no need to use the preview button.

Using hyperfocal distance

1. Set up your shot, making sure you get a good balance of foreground and background elements in the composition.

2. Check the focal length and aperture you’ve set, then find the hyperfocal distance on your chart or smartphone app.

4. Choose an object at the hyperfocal distance and focus on it. Live view is excellent for accurate manual focusing.

5. Once you’ve taken the shot, zoom in on the review image and check sharpness in the foreground and background.

6. The final image should display perfect front-to-back sharpness running through the entire picture.

Diffraction

When light passes through a lens aperture, the light striking the edges of the diaphragm blades get scattered, or diffracted. This reduces image sharpness. As the aperture is stopped down, a greater percentage of light is diffracted and the image becomes progressively softer. Therefore, although depth of field increases, overall image sharpness also deteriorates, so as a general rule it’s best to avoid extremely small apertures such as f/22.

However, in practice there are a number of factors that can influence the effects of diffraction, such as the number of aperture blades in the lens, and therefore how good the aperture circle is, and the subject matter of the image. You also need to consider that other factors, such as shutter speed, will influence the aperture you choose. Generally, though, an aperture of around f/11 often provides the best compromise between achieving sufficient depth of field and reducing diffraction.

Shooting with an aperture of around f/11 will often provide the best compromise between depth of field and diffraction

Don’t get carried away

While it can be tempting to set hyperfocal distance focusing all the time, think about the image you’re applying it to

Occasionally, those new to the technique will routinely set the hyperfocal distance for every landscape shot they take, even if there’s nothing in the immediate foreground. While this doesn’t necessarily lead to bad results, it can mean that you’re using depth of field where you don’t need it – in the foreground – and that the background, while acceptably sharp, could be sharper.

When there is no close foreground interest, it’s better to check what the hyperfocal distance is and then, if the nearest object to the camera is beyond the hyperfocal distance, focus on that object, or just slightly beyond it.

When there is no foreground interest close to the camera, it’s best to ignore the hyperfocal distance and focus on your main subject instead

Check calculations

There’s no rule that says you have to have front-to-back sharpness in landscape images, so don’t be afraid to experiment with limited depth of field. Use the depth of field preview button to see the effect before you take the shot

Tilt and shift lenses

With foreground interest close to the camera, sometimes the only way to get enough depth of field is to stop the lens right down, but the resulting image may end up soft due to the effects of diffraction. One way around this is to use a tilt-and-shift lens.

These are specialist lenses, which have movements that allow you to tilt the plane of focus, thus extending depth of field. This means that you can shoot at the lens’s ‘sweet spot’ of around f/8, while still obtaining front-to-back sharpness.

These two images show the difference between shooting at f/8 with no tilt (left), and at the same aperture and focused on the same point with tilt applied (right)

Kit list for mastering hyperfocal distance

Prime lenses

To make setting the hyperfocal distance really easy, use prime lenses with clear distance scales – you won’t even need to use a chart.

Tape measure

Not everyone is good at estimating distance, so when accuracy is important a tape or laser measure can help you find an object at the hyperfocal distance.

Tripod

A tripod not only helps you with setting precise composition, but also means you know exactly where the sensor plane is when calculating or measuring distances.

Live view

Precise focusing is essential for getting the depth of field you want, so if your camera has a live-view facility, use it.

For a more general guide to depth of field, see our depth of field guide.

Mark Bauer has been a full-time landscape photographer for more than a decade and takes inspiration from the landscapes in the southwest. www.markbauerphotography.com