Olympus OM-D E-M5 Mark II at a glance

- 16-millon-pixel, Four Thirds sensor

- 40-million-pixel high-resolution composite mode

- ISO 100-25600 (extended)

- 3in, 1.04M-dot LCD

- 2.36M dot EVF, 0.74x equiv magnification

- 1/8000sec max shutter speed

- Price £900 body only

Three years ago Olympus turned the compact system camera market on its head with the launch of the OM-D E-M5. This enthusiast-oriented model packed a groundbreaking 5-axis image stabilisation system into its compact, weatherproof, and handsomely retro-styled body. With an improved sensor compared to previous Micro Four Thirds models, it also offered image quality competitive with most APS-C SLRs. It rapidly became a favourite among photographers looking for a high quality system without the weight and bulk of an SLR, and in both 2013 and 2014 it was the most popular CSC among users of the photo-sharing site Flickr.

With the OM-D E-M5 Mark II, Olympus is clearly attempting counter the threat of more recent competitors, such as the even-more-retro Fujifilm X-T1 and the full frame Sony Alpha 7 series. In the absence of a new sensor to play with, it still uses a 16-million-pixel Four Thirds MOS chip, but almost everything else about the camera has been tweaked, revised and updated.

The camera’s headline trick is a new 40-million-pixel composite shooting mode, although as we’ll see later, this comes with some serious limitations. Apart from that, the E-M5 Mark II gets a larger, clearer electronic viewfinder, a fully-articulated LCD, a vastly-improved control layout, and an improved super-quiet shutter. And that’s just the start of it.

Take a look at our Olympus OM-D E-M5 Mark II image samples gallery

Features

From the front the E-M5 Mark II resembles Olympus’s classic 35mm OM SLRs

We’d hope to get a lot for our money from a £900 camera, but the E-M5 Mark II almost redefines the phrase ‘fully-featured’; indeed it’s simply not possible to cover everything here (if you’d like to explore in depth, we put together an exhaustive guide to the 57 differences between this camera and its predecessor). But let’s start with the basics. The camera offers a standard sensitivity range of ISO 200-25600, with an extended ISO100 option also available (but more likely to clip highlight detail). Shutter speeds range from 60 sec to 1/8000 sec – good for shooting with fast lenses in bright light – and there’s a completely silent electronic shutter option with a 1/16,000sec top speed. At the other end of the scale, Olympus’s unique Live Bulb, Live Time and Live Composite modes take the guesswork out of long-exposure shooting, giving an on-screen update of how the image is developing.

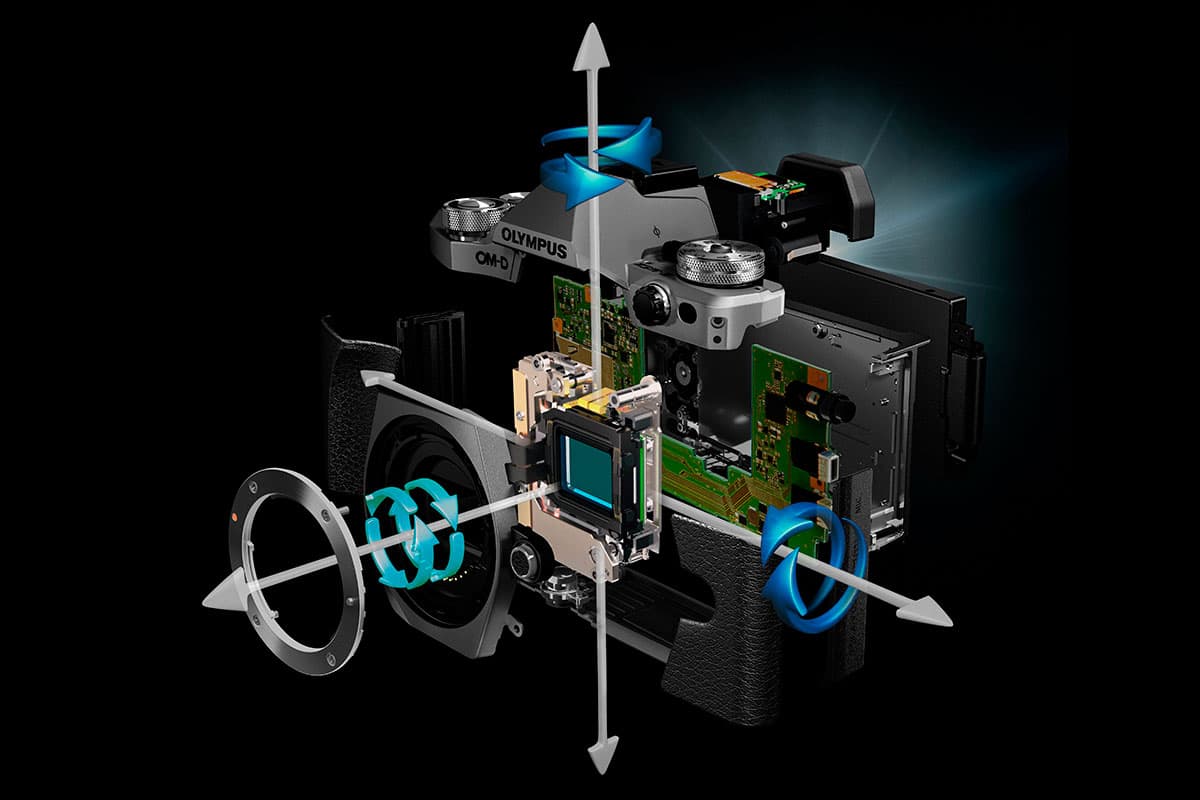

Naturally Olympus’s 5-axis in-body image stabilisation is on-board; it works with all lenses, including manual focus optics on mount adapters. It does an exceptional job for both stills and video, giving sharp images at implausibly slow shutter speeds, and bringing an almost Steadicam-like quality to handheld video. For example I was able to get sharp shots using a shutter speed of 1/6sec with a 60mm lens – more than four stops slower than I’d usually expect to get away with.

The 5-axis in-body IS has been updated to promise 5 stops of stabilisation – which it appears to deliver

Continuous shooting is available at 10 frames-per-second, or 5 frames-per-second with continuous AF and a live view display between frames. The buffer is sufficient for capturing 16 RAW frames before the camera slows down. The Mark II also features a highly customisable self-timer and built-in intervalometer, which it can use to create in-camera timelapse movies.

Other features include the obligatory built-in Wi-Fi, for image sharing and remote control of the camera. There’s also a large set of image-processing ‘Art Filters’ for looks such as Toy Camera and Grainy Film. While these aren’t everyone’s cup of tea, Olympus’s are unusually well-judged, and critically allow you to record a raw file alongside your filtered JPEG in case you change your mind later. In-camera High Dynamic Range (HDR) shooting and a double exposure mode are also available, but surprisingly there’s no automated in-camera panorama stitching mode.

The hotshot accepts Four Thirds-dedicated Olympus, Panasonic and third party flashes, as well as the small unit that comes in the box. A small, easily-losable cover on the front of the camera unscrews to reveal a standard coaxial PC sync socket for use with studio flash systems.

The supplied splashproof FL-LM3 has a bounce head and can act as a wireless commander

I also have to mention the FL-LM3 flash that comes in the box. While it’s not especially high-powered, with a guide number of 12.9m at ISO 200, it has a fully articulated head, allowing the light to be bounced off a ceiling for a more flattering effect indoors. Using a fast lens and relatively high ISO, this works genuinely well. It’s also splashproof and can act as a wireless controller for off-camera flash setups. Overall it has to be the most useful flash unit that comes supplied with any camera.

Arguably the most comprehensive changes have been made to movie shooting, where the Mark II looks like a far more serious tool them previous OM-Ds. There’s no 4K, but Full HD recording is on offer at choice of frame rates up to 60fps. The bit-rate is much higher (up to 77 MBPs) for better-quality footage, sound-recording options have been expanded, and clean HDMI can be output to an external recorder. A full set of touchscreen-based controls have also been added, including the ability to pull focus from one subject to another just by touching the screen. Combined with the remarkable image stabilisation and Olympus’s traditionally-excellent colour output, this makes the E-M5 Mark II a really interesting option for movie makers who don’t want to be encumbered by stabilisation rigs, or spend ages on post-processing.

Viewfinder and screen

The OM-D E-M5 Mark II’s screen is now fully articulated

Both the viewfinder and rear screen gain significant updates compared to the E-M5. The electronic viewfinder is superb; large and high resolution, in real-world use it’s a match for any other premium compact system camera, and indeed as large and sharp as the optical viewfinders of full frame SLRs. One feature I appreciate is how it adapts its display brightness to match the ambient light conditions. A viewfinder eye sensor automatically switches from the LCD to the EVF when you bring the camera up to your eye. It’s disabled when the screen is folded out, at which point the EVF can’t be used.

The 1.06M dot rear screen is both higher in resolution than the E-M5’s and visibly more colour-accurate, but the biggest change is that it’s now fully articulated. This makes it useable as a waist-level finder when shooting in portrait format, which I like a lot. But the catch is that it interferes with the microphone, HDMI and remote release ports on the camera’s left hand side. To be fair, given the camera’s tiny size there’s not a lot Olympus could do about this, short of pointing all of the connectors out of the front of the camera instead.

One problem with the articulated screen is that can clash with a remote release. Using a remote cable or microphone also compromises weathersealing, as opening the shared cover exposes all three connectors

Olympus has obviously been working hard on making the most of fully-electronic viewing as a tool for pre-visualising your images, to offset any perceived disadvantages compared to optical viewfinders. Exposure, depth of field and any chosen picture effects can all be previewed live, and the display can be overlaid with a wealth of information including electronic levels and a live histogram. You can even preview the effects of the camera’s built-in HDR and perspective correction modes. This is hugely useful while shooting, taking the guesswork out of changing exposure settings, and something DSLRs simply can’t match.

Build and handling

The OM-D E-M5 Mark II is a small camera, but handles well

It can be easy to go overboard when talking about build quality, but here the E-M5 Mark II absolutely excels. There wasn’t much wrong with the E-M5, but the Mark II feels even more solid and better made, and it’s splash-, dust- and freeze-proof, at least with appropriate lenses. The one disappointment is the cover for the three connectors on the left side of the camera, which feels thin and flimsy. Once open it exposes all three ports, inevitably compromising weathersealing.

Handling is, quite simply, excellent, and a significant improvement on its predecessor. Indeed the Mark II has adopted essentially the same control setup as the flagship OM-D E-M1. Two large control dials change the main exposure settings, and are ideally placed under your index finger and thumb for easy operation. The exposure mode dial is lockable by pressing down the button in its centre, but can be left unlocked if you prefer – a nice touch.

The twin control dials are well positioned, and the mode dial can be locked

I always felt that the E-M5 was a little short of buttons, and the Mark II addresses this by adding a couple more, which by default activate depth of field preview and HDR shooting. I don’t much like the HDR button, as it’s too easy to press accidentally, completely changing the camera’s set-up in the process. But like practically every control on the camera it’s user-customisable, so I set it to access ISO and white balance instead. I then changed the switch on the camera’s back that usually does this job to select between autofocus and manual.

The take-home message is that if you’re prepared to spend a bit of time tinkering, you should be able to set up the camera to your liking. But the complexity of Olympus’s menu system, combined with some far-from-obvious labelling, means that there’s a very long learning curve to fully master the camera.

It’s worth bearing in mind that the E-M5 Mark II is, at 123.7 x 85 x 44.5mm, a fairly small camera, and much closer in size to the OM series 35mm SLRs from which it draws design inspiration than it is to modern DSLRs. It also has a rather minimalist hand-grip, which helps to maintain a small-camera feel. Personally I quite like it, but I suspect many users will prefer to use one of the add-on grips that are available.

The BLN-1 battery is rated to 310 shots per charge, so you’ll probably want a spare. The tripod socket is in-line with the lens, but close to the front of the body

Focusing

With its reliable face detection autofocus, the E-M5 Mark II has no trouble focusing on off-centre subjects. This example was shot using the relatively inexpensive Olympus m.Zuiko Digital 45mm f/1.8 lens wide open.

We’ve become used to CSCs offering fast, accurate autofocus, and the E-M5 Mark II is no exception. Its 81-point contrast-detect AF system covers most of the frame, and can automatically switch to face detection when it detects a human subject. At this point it will even detect and focus on the closer eye, which is usually what we want to do. When using the EVF, the focus area can be set using the D-pad on the back of the camera; with the LCD it can be selected by simply tapping the screen.

Traditionally CSCs have not been so great at following moving subjects, but the manufacturers have made great strides here in recent years. The Mark II isn’t top of the class, as it has no phase detection elements on the sensor and therefore can’t match the likes of the Samsung NX1, Sony Alpha 6000 or its big brother the E-M1. Instead it can ‘only’ shoot at 5fps with continuous AF, which will likely satisfy many users. But if you spend a lot of time shooting fast-moving subjects, it might not be your best choice.

For manual focus, both an image-stabilised magnified view and a focus peaking display (that detects and highlights high contrast edges) are on hand to help with critical focusing. The two can be combined, and the latter is nicely customisable, with a choice of highlight colours and intensities. I found peaking worked well both with modern, native primes and older manual focus optics – but magnified view gives the very best accuracy.

Performance

In its default Natural colour mode, the E-M5 Mark II gives lovely colours which are vivid without being unnatural

So how about image quality? Well in 16MP mode the Mark II behaves much the same as other current Olympus models. The TruePic VII processor brings some image-processing advantages compared to the old E-M5, most notably automatic removal of colour fringing due to the lens’s lateral chromatic aberration, but aside from that, the output is much the same as before.

On the plus side, this means you get Olympus’s usual excellent JPEG processing. In its default ‘Natural’ mode the Mark II gives lovely saturated colours that are vibrant but not unrealistic, and its auto white balance tends to the warm side, giving a lift to even the dullest day. Noise reduction is a little heavy-handed by default, though, and personally I turn the ‘Noise Filter’ setting down to maximise detail rendition.

If you’re looking for something a little different, Olympus’s Art Filters offer some attractive alternative image processing options. Personally I’m a fan of the high contrast monochrome ‘Grainy Film’ mode, and the new ‘Vintage’ filters also give some interesting results. Crucially Olympus gives you more control over how the images turn out than many of its competitors, and you can shoot Raw files alongside in case you change your mind.

This portrait comes straight out of the camera, using Olympus’s atmospheric ‘Grainy Film’ Art Filter

The 16MP resolution may not sound to great on paper when most APS-C competitors are around the 24MP mark, but it’s important to keep this in context. It’s still plenty enough to make a nice A3 print, which I suspect is the largest most photographers will contemplate. And if you need more, there’s always the 40MP composite mode.

When it comes to high ISO noise, the Mark II also lags a little behind its APS-C competitors when compared like-for-like. I’m perfectly happy shooting it up to ISO 1600, and ISO 3200 at a push, but beyond that image quality clearly suffers, with noise reduction impacting on fine detail and little shadow detail to be seen. With most APS-C models I’d be happy shooting at a stop higher ISO.

If you’re after the very best in resolution or low noise, then, the Mark II may not be for you. But to me the gap against APS-C isn’t huge in practice, and frequently negated by the impressive image stabilisation system, which lets you use longer shutter speeds and lower ISOs. The availability of reasonably affordable fast prime lenses also helps, and lenses like the Panasonic 20mm f/1.7 and Olympus 45mm f/1.8 are so small you can carry them around all day without really noticing.

40MP composite mode

The Mark II’s 40MP composite mode is ideal for shooting highly detailed static subjects

The Mark II’s headline trick is undoubtedly its 40-million-pixel composite ‘High Res Shot’ mode. This works by taking 8 images, using the camera’s in-body stabilisation system to move the sensor fractionally between them on order to sample the scene in higher detail. The camera has to be fixed solidly to a tripod for this to work, and because it’s a multiple-exposure process that takes at least a second to complete, anything that moves will show ghosting artefacts.

The mode first has to be turned on in the camera’s menu; this allows you to define a delay before the picture is taken (to allow any vibrations to die away), and even specify a wait time between exposures to allow flash units to recharge, if you’re shooting in the studio. Slightly strangely High Res Shot is then accessed as a drive mode, rather than as a resolution setting where you might expect to find it. You can decide whether or not to record raw files independently of your usual choice in 16MP mode; by default, this option is turned off.

The 8-shot composite raw file is vast – 100MB or more – and recorded with an ‘ORF’ extension, but the camera also writes a conventional 16MP raw of the first exposure with an ‘ORI’ extension. This gives a safety net in case something goes wrong, for example you inadvertently shoot in High Res mode hand-held. Composite raw files can be re-converted in-camera to 40MP JPEGs, with the usual options to tweak exposure, white balance etc. Currently you don’t get the choice to make a 16MP file from the first exposure, but if you rename the ORI file to an ORF using a computer and re-insert the memory card, the camera will recognise it as usual and let you make a 16MP JPEG.

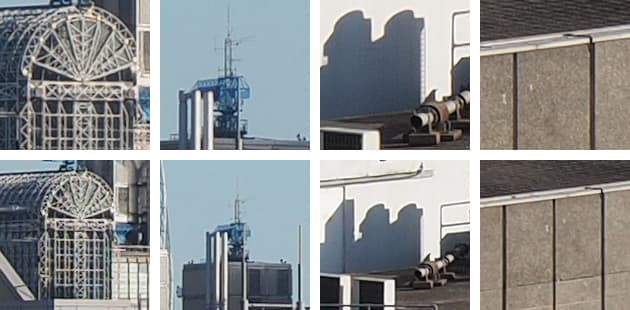

Here we’re showing comparison crops from images shot at the same time in 40MP mode (top) and 16MP mode (below). In all cases the 40MP version shows visibly more detail and fine texture, and fewer colour artefacts.

There are a number of limitations on exposure settings. Olympus won’t allow you to set an aperture smaller than f/8, because diffraction blurring at smaller settings will negate the mode’s usefulness, and the longest available shutter speed is 8 seconds to avoid the build-up of thermal noise. The maximum sensitivity is limited to ISO 1600, but it’s worth noting that because this is a multi-shot process that effectively averages noise, the images remain impressively clean.

It’s also important to use a good lens; Olympus’s ‘Pro’ series zooms and fast primes should be able to resolve sufficiently across the frame to deliver the additional detail, but cheaper lenses will struggle with resolving enough detail towards the corners. Ironically this includes both the 12-50mm and 14-140mm zooms that will be sold in kits with the Mark II.

However, when it does work, the high-resolution composite images are impressive. Visibly more detail is recorded compared to 16MP mode, and while it’s perhaps not as much as you’ll get from a 36MP full frame sensor, the difference is very small. Colour moiré is effectively eliminated, too, and noise is very low, even at higher ISO settings. Even so the High Res mode is only suitable for static subjects, and to be honest, nowhere near as practical as simply using a camera with a high-resolution sensor.

You can see more analysis of the 40MP mode on the Resolution and Detail and Noise pages of this review.

But what about when it goes wrong?

When the 40MP mode goes wrong, it tends to do so quite spectacularly. In the example below, I tried unsuccessfully to shoot using a railing as a support. But the camera moved fractionally between shots, and various objects moved in front of the camera too, resulting in a salutary lesson in how not to use a multi-shot mode.

In this 40MP shot, just about everything that can go wrong, did.

This boat had the temerity to move during the process, and ended up as an unrecognisable mess

The camera also moved slightly between frames, and this 100% crop reveals a disastrous impact on image quality.

But my favourite artefact is this ghost bird, captured differently in the separate exposures as it flew across the frame

The take-home message here is that you can’t expect to be able to get way with a lot of the camera support tricks you might use for normal shooting if you’re not carrying a tripod with you; instead you absolutely have to use a rock-steady support. Of course, with the E-M5 Mark II’s compact size and small lenses, you can get away with using a relatively lightweight tripod compared to what you’d need for an SLR.

Obviously you also need to take care to avoid having moving subjects in your photos. If you’re taking photographs with moving water, then it probably makes sense to use a strong neutral density filter to blur it, which should give better results than overlaying eight ‘freeze frames’. There’s probably also scope for using the 16MP .ORI file to help patch out any moving subjects, albeit at reduced resolution.

Image quality

The Olympus OM-D E-M5 Mark II uses a 16-million-pixel Four Thirds sensor, which is basically the same as the one used in the E-M5 three years ago. This means that it can’t technically match its APS-C competitors, particularly for noise at any given ISO. It gives good results up to ISO1600, but ISO 3200 is marginal, and the higher settings for use only when there’s no other choice. However the new 40-million-pixel High Res Shot mode is very impressive indeed, giving both excellent resolution and low noise. Photographers who shoot JPEGs will also appreciate Olympus’s attractive colour rendition.

Resolution

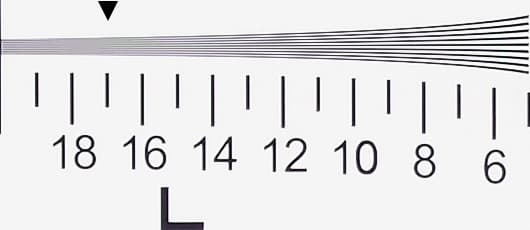

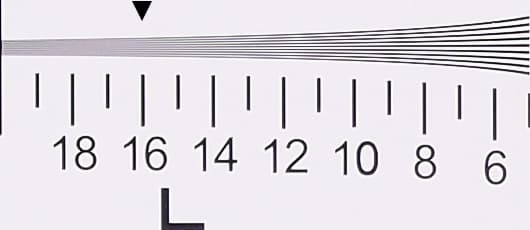

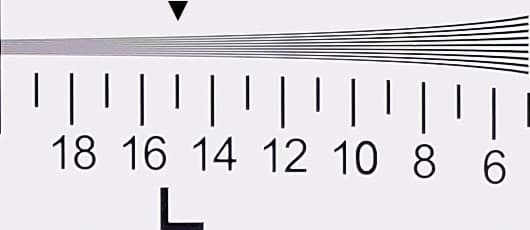

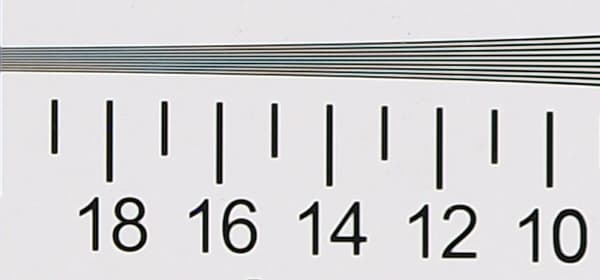

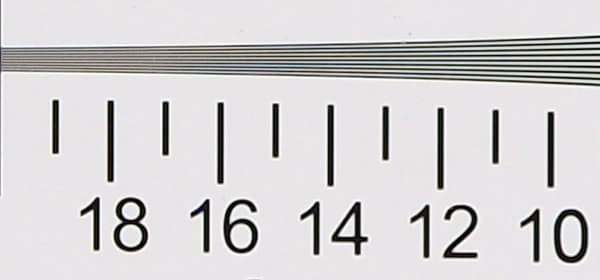

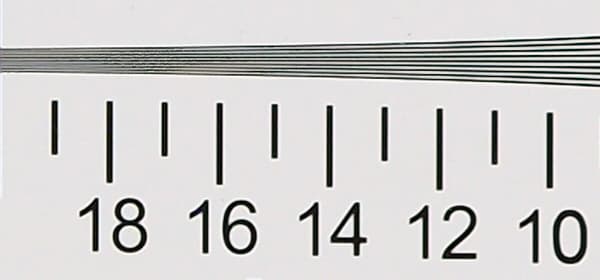

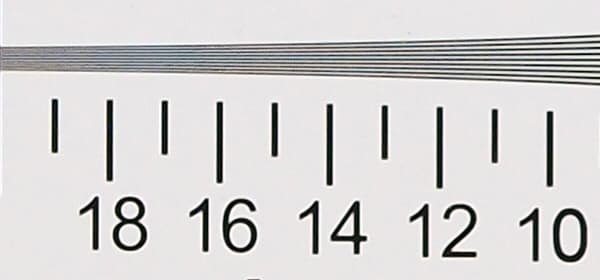

The E-M5 Mark II resolves around 3400 l/ph at ISO 100 in our resolution tests, which is close the theoretical maximum its 16MP sensor could achieve. This falls gradually as the sensitivity is raised and the effects of noise and noise reduction take their toll, to around 3000 l/ph at ISO 1600. Past this though things deteriorate more rapidly, to about 2600l/ph at ISO 6400 and just 2200 l/ph at ISO 25600.

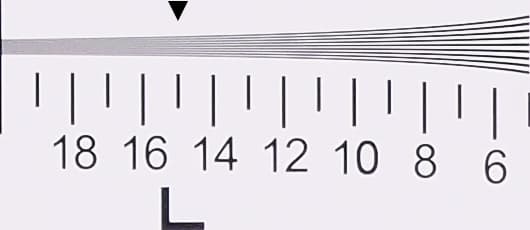

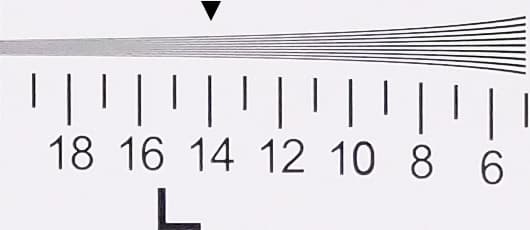

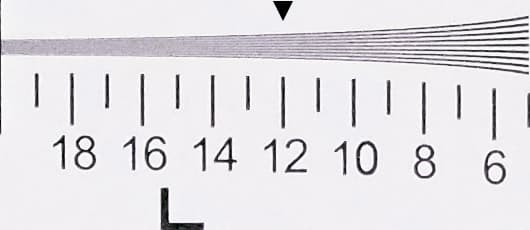

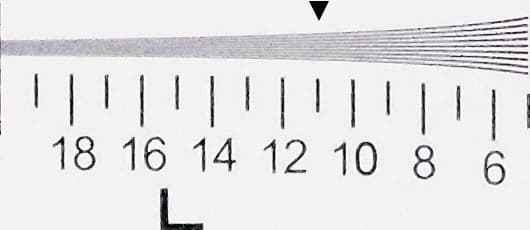

Below we show 100% crops from our resolution chart at each ISO, with a black triangle indicating our estimate of limiting resolution. Multiply the numbers by 200 to give the resolution in lines/picture height.

Olympus OM-D E-M5 Mark II resolution, ISO 100

Olympus OM-D E-M5 Mark II resolution, ISO 200

Olympus OM-D E-M5 Mark II resolution, ISO 400

Olympus OM-D E-M5 Mark II resolution, ISO 800

Olympus OM-D E-M5 Mark II resolution, ISO 1600

Olympus OM-D E-M5 Mark II resolution, ISO 3200

Olympus OM-D E-M5 Mark II resolution, ISO 6400

Olympus OM-D E-M5 Mark II resolution, ISO 12800

Olympus OM-D E-M5 Mark II resolution, ISO 25600

Resolution: 40MP mode

Switch the OM-D E-M5 Mark II to 40MP composite mode, and the resolution can surpass 4000 l/ph at ISO 100, which is pretty impressive. Because this is a multi-shot mode, noise has less of an impact as sensitivity is increased, with resolution dropping to around 3600 l/ph at ISO 1600. This is still higher than the camera can manage at low ISO in standard 16MP mode.

Olympus OM-D E-M5 Mark II resolution, 40MP mode, ISO 200

Olympus OM-D E-M5 Mark II resolution, 40MP mode, ISO 400

Olympus OM-D E-M5 Mark II resolution, 40MP mode, ISO 800

Olympus OM-D E-M5 Mark II resolution, 40MP mode, ISO 1600

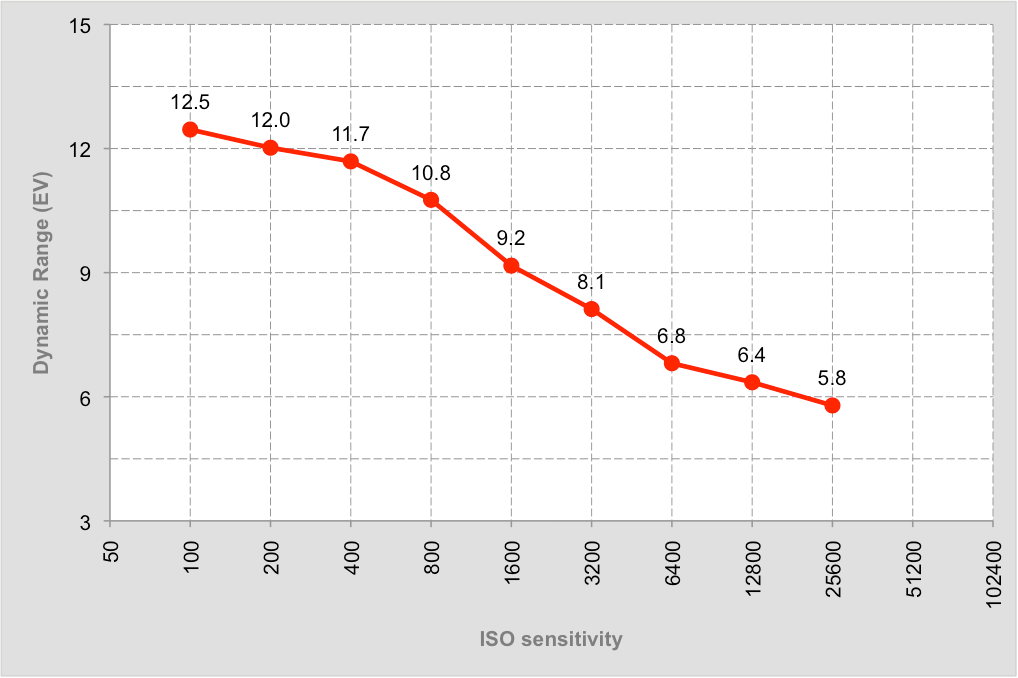

Dynamic Range

As you can see from the Dynamic Range chart, the E-M5 Mark II does well in our Applied Imaging tests, registering an impressive 12.5EV at ISO 100. It holds up OK to ISO 400 but thereafter drops off quite quickly, indicating that shadow noise will becomes increasingly visible. At ISO 1600 we still see a respectable 9.2 EV, and ISO 3200 gives a just-about-acceptable 8.1 EV. But the top three ISO settings all show very low figures, suggesting that detail will be swamped by noise, especially in the shadow regions.

Detail and Noise

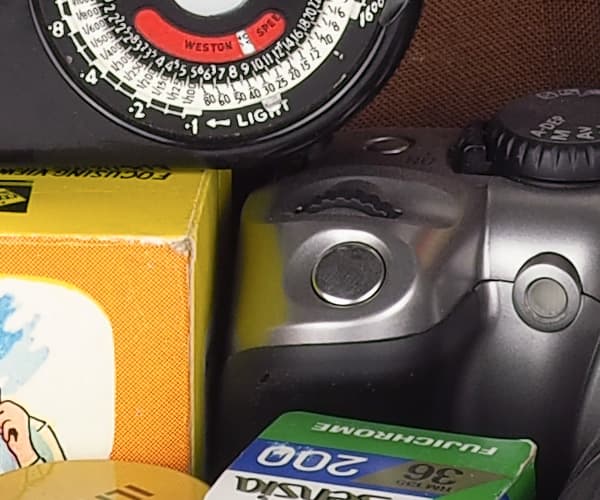

At its lowest standard sensitivity of ISO 200, the E-M5 Mark II gives clean images with attractive colours and lots of fine detail. ISO 100 is, if anything, even cleaner, but this comes at the cost of earlier highlight clipping. Stepping up through the sensitivity range shows that excellent results are still obtained at ISO 800, although with some loss of detail both in the shadows, and in finely-textured patterns. By ISO 3200 almost all fine detail has been blurred away by noise reduction, and shadows are being clipped to hide visible noise; but colours remain strong and saturated, meaning that images still look quite attractive overall. The top three settings, though, look increasingly stretched.

Olympus OM-D E-M5 Mark II ISO 100 JPEG, 100% crop

Olympus OM-D E-M5 Mark II ISO 200 JPEG, 100% crop

Olympus OM-D E-M5 Mark II ISO 400 JPEG, 100% crop

Olympus OM-D E-M5 Mark II ISO 800 JPEG, 100% crop

Olympus OM-D E-M5 Mark II ISO 1600 JPEG, 100% crop

Olympus OM-D E-M5 Mark II ISO 3200 JPEG, 100% crop

Olympus OM-D E-M5 Mark II ISO 6400 JPEG, 100% crop

Olympus OM-D E-M5 Mark II ISO 12800 JPEG, 100% crop

Olympus OM-D E-M5 Mark II ISO 25600 JPEG, 100% crop

40MP composite mode

Switch to 40MP mode and camera can resolve visibly more detail and texture. Because it’s a multi-shot mode, noise is also kept very low up to the maximum available sensitivity of ISO 1600. In the crops below you can see visibly more fine detail and texture compared to the 16MP versions, with the image staying pretty clean at ISO 1600 (where usually the fine detail is blurred-away by noise reduction).

Olympus OM-D E-M5 Mark II, 40MP mode, ISO 100 JPEG, 100% crop

Olympus OM-D E-M5 Mark II, 40MP mode, ISO 200 JPEG, 100% crop

Olympus OM-D E-M5 Mark II, 40MP mode, ISO 400 JPEG, 100% crop

Olympus OM-D E-M5 Mark II, 40MP mode, ISO 800 JPEG, 100% crop

Olympus OM-D E-M5 Mark II, 40MP mode, ISO 1600 JPEG, 100% crop

Conclusion

With its large, bright, high resolution EVF the Mark II is a joy to shoot with.

First of all, a disclaimer – I own and use an OM-D E-M5, so I’m naturally inclined to like the Mark II. But what’s struck me most, comparing the two side-by-side, is just how much work Olympus has done on improving the camera’s design and usability. All the little tweaks to the control layout really add up, and once set up to my liking, I’ve found the E-M5 Mark II to be a really excellent little camera to shoot with.

Indeed where the original the original E-M5 was a trailblazer for its type, the Mark II sees the concept of the small SLR-like CSC refined to being a really serious photographic tool. The superb electronic viewfinder, fully articulated screen, wonderfully quiet shutter, and extremely effective in-body image stabilisation system combine to make an exceptionally capable camera. The tiny bundled flash is unusually useful, with its bounce head and ability to act as a wireless commander, and the highly-improved movie features should make the Mark II very interesting to videographers.

Of course the big question is how the E-M5 Mark II stands relative to its peers. It lags behind a little APS-C cameras with regard to raw image quality, particularly in terms of noise at high ISOs, but on the other hand it offers very attractive out-of-camera JPEGs. And let’s not forget that the Micro Four Thirds mount allows use of a wide range of lenses from both Olympus and Panasonic, many of which are very small, yet optically excellent; a direct advantage of the smaller sensor.

Camera choice is all about compromises, and ultimately the E-M5 Mark II offers a hugely impressive feature set in a very portable package. The original E-M5 was extremely popular, and its replacement is a considerably better camera. For SLR owners looking to take the weight off their shoulders without sacrificing much capability, it’s a very compelling option.