Sigma fp: At a glance

- £1,999 body only

- £2,399 with 45mm f/2.8 DG DN lens

- 24-million-pixel full-frame sensor

- ISO 6-102,400

- 18fps shooting

- 3.1in, 2.1m-dot fixed touchscreen LCD

- 4K video recording

Sigma is best known as one of the finest third-party lens makers, but it’s always had an interest in making cameras too. The firm long ago learned that there’s little point in competing directly with the likes of Canon and Nikon by making identikit DSLRs, so its digital models have always been slightly off the beaten track. It was the first to make a compact camera with a large sensor for higher image quality, with the DP1 in 2008, and has developed this concept ever since. Its latest model follows a similar theme, but takes another step up: it’s the world’s smallest interchangeable-lens camera with a full-frame sensor. The fp name comes from the musical notation ‘forte-piano’ meaning ‘loud and soft’, suggesting high performance in a discreet, unassuming package.

Indeed according to Sigma CEO Kazuto Yamaki, the design concept was very simple: to make the smallest possible full-frame camera for travel. To this end, the firm has removed everything but the essentials needed to make the camera work. So there’s no viewfinder, with just a fixed rear LCD for composing your images. The mechanical shutter has also been left out, leaving the camera reliant on an electronic shutter, and if you want to use an external flash, this requires bolting a hot-shoe adapter onto the side. Indeed the fp is designed to be modular, with the option to add various grips and accessories to meet each user’s needs. It’s a really interesting concept, and quite unlike anything else you can buy.

The fp is significantly smaller than the Sony Alpha 7 III, although perhaps not by as much as you might think once a lens is attached

But just how small is the Sigma fp, really? The body is a rectangular box measuring 113 x 70 x 45mm, making it comparable to a Sony Alpha 7 III with the viewfinder removed from the top and the handgrip from the front, and 14mm taken off one side. It’s similar in size to compact APS-C models such as the Canon EOS M6 Mark II, Fujifilm X-T30, or Sony Alpha 6400. But of course you need a lens, with the matched Sigma 45mm F2.8 DG DN adding 46mm to the depth and giving a total weight of 640g. This combination is small by full-frame standards, but is still larger and heavier than the fixed-lens Sony RX1R II, which sports a 42.4MP full-frame sensor, 35mm f/2 lens, pop-up viewfinder and tilting screen, but costs £600 more.

Sigma fp: Features

As Sigma’s first camera born of its alliance with Leica and Panasonic, the fp is based around the mirrorless Leica L mount. Not only can it use native lenses from all three companies, but also adapted Canon EF or Sigma SA-mount lenses via the Sigma MC-21 adapter. Officially, only the firm’s Global Vision-series lenses made since 2012 are fully compatible with the MC-21, but in practice, every Canon EF lens I tried worked fine, although autofocus tends to be slow. As with all mirrorless cameras, a huge array of manual-focus lenses can also be used via mount adapters.

In contrast to all of the firm’s previous models, which used multi-layer Foveon sensors for full-colour sampling at each pixel location, the fp’s 24MP full-frame sensor employs a conventional Bayer colour filter array. This should massively broaden the fp’s appeal, as it delivers considerably higher dynamic range and lower high-ISO noise. The sensor employs a back-illuminated architecture to increase light-gathering sensitivity, while detail rendition is maximised by the omission of an optical low-pass filter.

The standard sensitivity range of ISO 100-25,600 is par for the course these days, as are the extended high settings up to ISO 102,400. But at the other end of the scale, Sigma has added a unique set of ‘composite’ settings down to ISO 6. Unlike on other cameras, these aren’t ‘pulled’ low ISOs with reduced highlight range; instead the camera takes a series of exposures at ISO 100 and adds them together. It’s a really neat trick that allows you to use long shutter speeds without needing a neutral density filter, while delivering raw files with ludicrous dynamic range that can easily be pushed five stops with no visible noise. The catch, as with other composite modes, is that anything moving within the scene will give multiple ghost images.

Autofocus uses contrast detection, with three different size AF areas that can be placed freely across approximately 80% of the frame width and 75% of its height. When moving the AF point using the physical controls rather then the touchscreen, it’s easiest to switch to a 49-point setup, arranged in a 7×7 grid. Naturally you can enable face- and eye- detection, at which point the camera will outline your subject and track them as they move around the frame.

In terms of shooting speed, the fp is capable of up to 18 frames per second, although with a buffer of just 12 frames. The shutter provides settings up to 1/8000sec, and being electronic, is entirely silent. Rolling shutter artefacts can be apparent if you pan the camera while shooting, but Sigma has done an decent job of suppressing the banding that can be caused by the flickering of LED or fluorescent lights when shooting indoors.

Raw files are recorded as 14-bit DNGs, so they should open easily in your existing raw converter, if perhaps without a perfect colour profile. Sigma has also included a good range of options for adjusting the camera’s JPEG colours, accessed using a dedicated button on the back. Alongside a conventional-sounding set of modes such as portrait, landscape etc, there are some more creative options with names like Teal & Orange, Sunset Red and Forest Green, each of which can be tuned in-camera.

Another button allows you to adjust the tone curve, with highlights and shadows set independently, and the impressive Fill Light feature familiar to users of Sigma’s raw processing software has been transposed into the camera itself. All of these options can also be applied retrospectively using the in-camera raw converter.

Other handy features include an intervalometer and a comprehensive array of bracketing options (exposure focus, white balance, colour mode and fill light). One thing that’s conspicuous by its absence, though, is any form of smartphone connectivity – neither Wi-Fi nor Bluetooth is included. Likewise image stabilisation needs to be provided by the lens: a form of electronic stabilisation is built-in, but only for JPEG shooters.

Videographers will find a lot to like, with the fp promising to be an excellent little camera for use in a rig or on a drone. It’s capable of recording 4K (3840 x 2160) video at 30 fps, and can output raw video in the 12-bit CinemaDNG format to an external recorder. One especially neat trick is that the camera can record directly to an external SSD, simply by plugging one into the USB-C port. This is such a useful idea that you have to wonder why the bigger camera firms haven’t adopted it before. The full scope of the camera’s movie capabilities goes far beyond what it’s possible to cover in a stills-focused review, but suffice to say, it has a lot of videographers very excited.

Sigma fp: Focal points

The compact-bodied, modular Sigma fp is quite unlike any other full-frame mirrorless camera.

- Sigma’s BP-51 battery is also used by the dp Quattro series, and is identical to the Panasonic DMW-BLC12, so spares are easy to find. It’s charged via the USB port, with a 1.8A supply included in the box.

- A large heat sink behind the LCD screen provides a means of preventing the camera from overheating during video recording.

- Along with the usual tripod thread on the baseplate, there’s another ¼ in socket on each side. They’re used for attaching accessories, handgrips and even the removable strap lugs.

- On the side you’ll find USB-C, microphone and micro-HDMI ports, alongside a connector for the add-on hot-shoe accessory. The mic socket also accepts the CR-41 cable release.

- The fp is designed to be dust- and splash-proof, with seals arranged at 42 points around the camera body.

- There’s a single UHS-II type SD card slot, but you can also record files to an SSD connected to the USB-C port, which should be especially handy for videographers.

- Color and Tone buttons on the back provide an access to a broad range of in-camera image-processing effects

Sigma fp: Build and Handling

When you first pick up the fp, it’s clear that this camera is built to withstand less-than-gentle conditions. Its die-cast aluminium body feels completely solid, and is sealed at 42 points against dust and moisture. The various buttons, dials and switches are large and well-spaced, and I rarely found myself operating anything inadvertently. Indeed despite the camera’s small size, it’s quite usable when you’re wearing gloves.

That brick-shaped camera body does, however, fit into your hand just as awkwardly as you might expect. It desperately needs something – anything – on the front plate to afford your fingers some purchase. Thankfully Sigma makes two accessory handgrips, with the smaller HG-11, which bolts onto the side of the body and wraps around the front and back, being the bare minimum you need. I used it as a matter of course with the 45mm f/2.8 and found it improved the handling immeasurably, the catch being that it adds £60 to the price. Meanwhile the larger HG-21 attaches to the baseplate, and is a better option with heavier lenses, but costs £100.

In contrast, the control layout and user interface is mostly excellent. Two large switches on top turn on the camera and select between the Still and Cine modes, with entirely independent settings and optimised interfaces for each.

A pair of electronic dials on the top and back set exposure parameters, with the rear one controlling exposure compensation in the P, A and S modes; however the dial functions can be exchanged if you prefer. This allows you to repurpose the larger top dial to exposure compensation when shooting with lenses that have physical aperture rings, such as the 45mm f/2.8. The rear dial also serves as a d-pad for navigating menus and changing settings.

Other key settings are changed using Sigma’s excellent onscreen Quick Set menu, which is accessed by a press of the QS button. Here you’ll find such things as ISO, white balance, metering and drive modes, along with image quality, aspect ratio and fill light options. There’s no exposure mode dial; instead this is changed using a button at the camera’s base.

On the whole, the controls operate with satisfying precision, aside from slightly ill-defined click-stops on the rear dial which can hinder changing settings quickly. Very little hardware control customisation is on offer, aside from defining whether the movie record button should be active in Still mode, and specifying how the AEL button should behave. But with an interface this well thought-out, you don’t necessarily need it.

One area where the fp is let down, though, concerns focus-area selection. Usually you’re expected to use the touchscreen, but when you tap on the subject, the response is disconcertingly laggy, with the camera taking almost a second to register the new AF point. Things are no better using the physical controls: you need to tap the down button of the d-pad, then AEL, and then use the d-pad, which is unnecessarily long-winded and requires a lot of thumb movement. It’s a shame the d-pad can’t simply be used to set the focus area directly.

Sigma fp: Viewfinder and screen

Another drawback becomes apparent when it comes to composing your images. With just a fixed rear screen, you’re forced to hold the camera out in front of you to take pictures, smartphone style. But with the fp being much heavier than a smartphone or conventional compact, it’s not a particularly stable pose, and this is exacerbated further if you fit a large lens. It’s a camera that’s crying out for a tilting LCD.

Thankfully the screen itself is excellent: at 2.1-million-dots it’s sharp and detailed, and bright enough to see clearly outdoors in daylight. It previews colour and exposure, and you can overlay useful information such as gridlines, an electronic level, a live histogram and zebra pattern overexposure warning. Pressing a small button beneath the LCD allows you to cycle through up to four display modes with user-definable levels of information. But one disappointing quirk is that, as with its L-mount cousin the Leica SL2, there’s no apparent way to preview depth of field.

If you really want to shoot with the camera at eye level, Sigma offers the LVF-11 LCD View Finder accessory for £289. This is a massive hood for the rear screen with a magnifying eyepiece, which attaches via either the BPL-11 baseplate that’s supplied with it, or the large HG-21 handgrip. It gives a huge view that surpasses any built-in electronic viewfinder by far, making it fantastic for fine-tuning focus and composition.

Indeed the magnification is so extreme that you can see the fine dividing lines between the LCD panel’s pixels. But it also makes the onscreen graphics look clunky and obtrusive (and the levels display in particular), which is compounded by the fact that the button for switching through display modes for a cleaner view becomes awkward to reach when you’re shooting at eye level.

The LVF-11’s biggest drawback, though, is that it has the unfortunate effect of turning the world’s smallest full-frame camera into one of the world’s bulkiest. It’s also impossible to remove quickly or hinge away from the screen, so you’re obliged to use it all the time, including for reviewing images, changing settings and navigating menus. This also means that it blocks any possibility of using the touchscreen, which forces you into using that tortuous method of selecting the AF-area. So if you really want to shoot using a viewfinder, you’d be better off buying a camera that’s got one built in.

Sigma fp: Autofocus

With the fp relying on contrast detection for AF, it’s never going to be the best choice for fast-moving action. But with static, or only slowly moving subjects it generally works just as well as we’d expect from a modern camera. It’s rapid, silent and inherently accurate, and has no problems focusing correctly on off-centre subjects with large-aperture lenses. In low light it perhaps has a greater tendency to hunt than its peers, but that can often be fixed by switching to a larger focus area.

Moving subjects pose more of a challenge. If you set the camera to AF-S and face detection, it’ll make a decent attempt to keep your subject in focus as they move, but not surprisingly, you can’t expect to get the same speed and hit-rate as you’d get from a high-end phase-detection system like that on the Sony Alpha 7 III. Having said that, the fp’s form factor lends itself far more to casual, across-the-table social shooting than anything that looks like action photography, and for this purpose it’ll do fine.

If you prefer to focus manually, the fp has some neat tricks up its sleeve. When using a native lens, turning the manual focus ring activates a detailed ‘picture-in-picture’ magnified view for accurate focusing. Focus peaking is also available, in a choice of colours, and the camera can display either a basic distance scale or the current focus distance.

With an adapted lens, pressing the button in the centre of the rear dial toggles magnified view, which is temporarily dismissed by a half-press of the shutter button for clearer composition. It all works very well, making the fp a fine vehicle for using small manual-focus primes.

Sigma fp: Performance

Previous Sigma models have tended to suffer from obvious operational flaws of one sort or another, but with the fp, the firm has created a camera that generally works very well. It does take noticeably longer than its peers to turn on when you flick the power switch, at about two seconds, and this will irritate those wishing to use it for quick grab shots.

But once it’s up and running, the fp responds snappily to the controls, and doesn’t often leave you waiting while it goes about its business. The only exception is when using composite low ISO settings, which tie up the camera for up to six seconds while they’re processed and stored. But given that you’ll probably be using them with slow, considered shooting on a tripod, that’s an acceptable price to play given the incredible clean files created. The example below was exposed for the highlights and has had huge shadow adjustments in raw processing, but shows no visible noise.

The fp isn’t the best choice if you wish the shoot and use JPEGs easily. Its metering is distinctly cautious, often giving underexposed images, and its auto white balance frequently veers towards the cool side. Its default Standard colour palette is also somewhat neutral and uninspiring, and as a result, its JPEGs often look dull and muddy. If you want attractive files directly from the camera, you’d be better off looking into cameras from the likes of Canon, Fujifilm or Olympus.

Raw files are, however, a different matter, and on the whole every bit as good as those from larger cameras with 24MP full-frame sensors, given a little bit of work in your favourite raw converter. There’s lots of fine detail thanks to the lack of a low-pass filter, dynamic range is excellent at low ISOs, and you can easily lift the shadows by three or four stops without any problem. Likewise, noise is kept impressively under control at high ISOs. The conservative metering also means that you rarely end up highlight detail being irretrievably lost.

The Sigma fp is a great vehicle for adapting small primes. Here I used an Olympus OM Zuiko 21mm f/3.5, which decorated the shot with lots of lens flare. 1/500sec at f/11, ISO 200

It’s worth noting that the fp’s battery life is nothing to write home about. Even obsessively managing the power, and switching the camera off whenever I wasn’t using it, I struggled to get 200 shots from a single charge. So if you tend to take a lot of pictures in a session, it’s best to make sure you have a spare or two, and maybe carry a powerbank to top up while you’re not shooting.

Sigma fp: Image quality

The whole point of full frame is image quality, and the fp’s 24MP back-illuminated sensor delivers this impressively well. Without an optical low-pass filter it records plenty of detail, while keeping noise extremely well under control. I’d be perfectly happy shooting at ISO 1600 without a moment’s hesitation, and up to ISO 12,800 if necessary.

Perhaps the biggest limitation on the fp’s image quality is its fully electronic shutter, which can give motion distortion and banding artefacts in some situations.

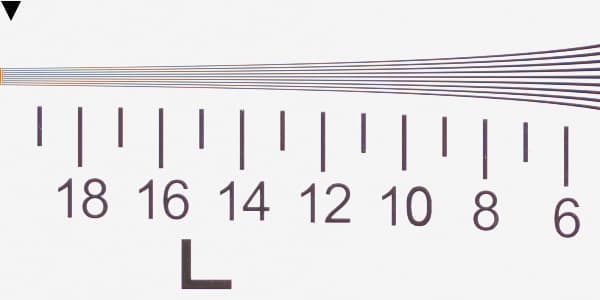

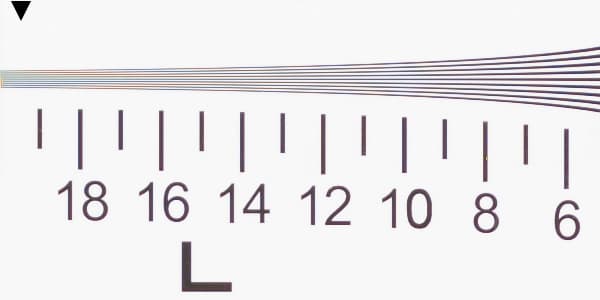

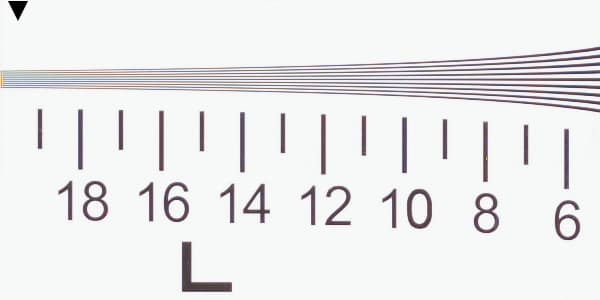

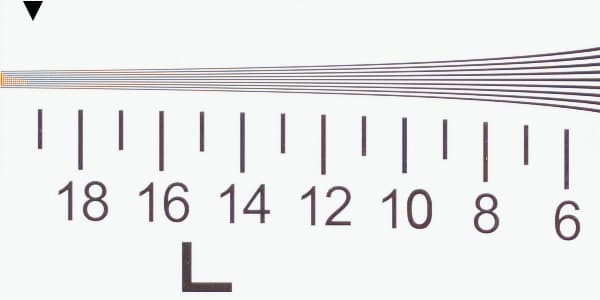

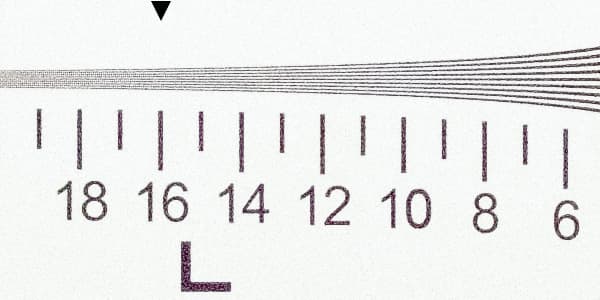

Sigma fp: Resolution

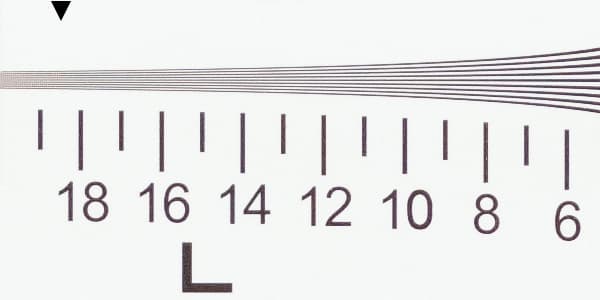

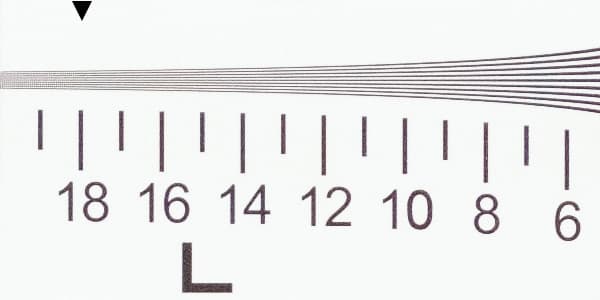

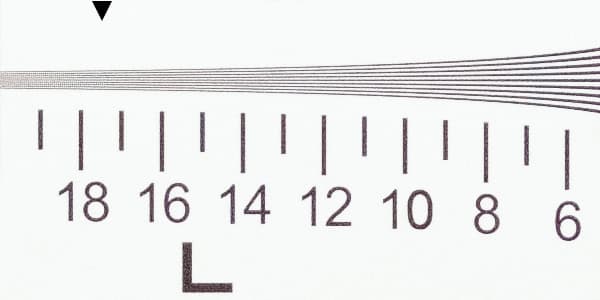

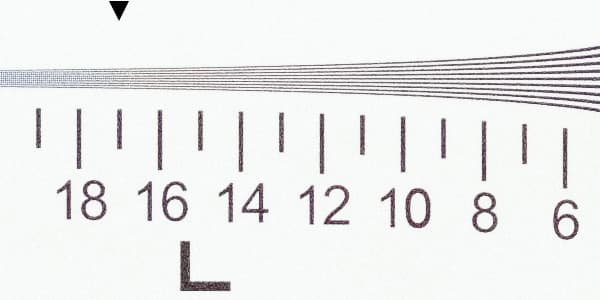

At low sensitivity settings, the fp cleanly renders every bit of the 4000 lines per picture height (l/ph) that its sensor is theoretically capable of delivering. Noise only starts to have any real impact at ISO 1600, at which point resolution drops to 3600 l/ph. Files stay remarkably clean at higher settings, and even at ISO 25,600, the sensor delivers an impressive 3,200 l/ph, Remarkably, even at the top ISO 102,400 option, resolution still surpasses 3000 l/ph. Using the 100% crops below taken from our resolution chart test shots, multiply the numbers beneath the lines by 200 to calculate the resolution in lines per picture height.

Sigma fp, resolution, ISO 6, raw + Adobe Camera Raw

Sigma fp, resolution, ISO 100, raw + Adobe Camera Raw

Sigma fp, resolution, ISO 400, raw + Adobe Camera Raw

Sigma fp, resolution, ISO 1600, raw + Adobe Camera Raw

Sigma fp, resolution, ISO 6400, raw + Adobe Camera Raw

Sigma fp, resolution, ISO 12,800, raw + Adobe Camera Raw

Sigma fp, resolution, ISO 25,600, raw + Adobe Camera Raw

Sigma fp, resolution, ISO 51,200, raw + Adobe Camera Raw

Sigma fp, resolution, ISO 102,400, raw + Adobe Camera Raw

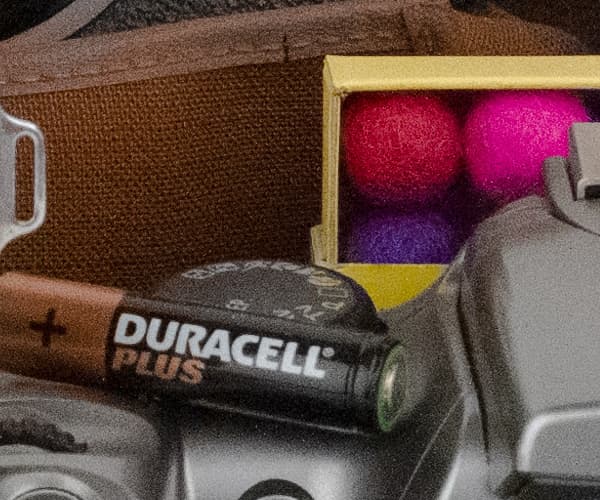

Sigma fp: Diorama

Wonderfully crisp, clean images are seen at ISO 100, with no hint of noise. Indeed there’s no immediately visible benefit to shooting at the low composite settings; instead they’re all about the ability to capture noise-free detail right down into the deepest shadows. Image quality also holds up impressively at ISO 1600, with just the slightest hint of noise creeping into files when viewed close-up onscreen. Detail and colour saturation continue to hold up well to ISO 12,800, but beyond this things take a turn for the worse. I’d use ISO 25,600 at a push, but avoid the higher extended settings due to faded, broad-brush colour and the lack of shadow detail.

Sigma fp, ISO and noise, ISO 6, raw + Adobe Camera Raw

Sigma fp, ISO and noise, ISO 100, raw + Adobe Camera Raw

Sigma fp, ISO and noise, ISO 400, raw + Adobe Camera Raw

Sigma fp, ISO and noise, ISO 1600, raw + Adobe Camera Raw

Sigma fp, ISO and noise, ISO 6400, raw + Adobe Camera Raw

Sigma fp, ISO and noise, ISO 12,800, raw + Adobe Camera Raw

Sigma fp, ISO and noise, ISO 25,600, raw + Adobe Camera Raw

Sigma fp, ISO and noise, ISO 51,200, raw + Adobe Camera Raw

Sigma fp, ISO and noise, ISO 102,400, raw + Adobe Camera Raw

Sigma fp: Verdict

On the simplest level, the Sigma fp is a straightforward camera to assess. If you demand full-frame image quality and interchangeable lenses in the smallest possible package, this is it. As long as you can live with the fixed screen and lack of a viewfinder, it’ll do the job and deliver excellent images. Indeed with the 45mm f/2.8 lens onboard, it’s a fine little camera that’s a lot of fun to shoot with. But it’s less successful when paired with larger lenses, so desperately needs more small primes of the same ilk to realise its full potential, perhaps a 28mm and a 90mm. Thankfully Sigma is a firm that fundamentally understands photography, so you can bet your bottom dollar it’s working on such lenses right now.

The bigger question, though, is whether it’s worth sacrificing so much for the size reduction compared to more mainstream models such as the Sony Alpha 7 III or Nikon Z 6. These boast built-in viewfinders, tilting screens, faster, more sophisticated AF systems, in-body image stabilisation, and better handling with a wider range of lenses, all for less money than the fp. Alternatively if size is crucial, a small APS-C camera like the Fujifilm X-T30 might be a better option, coupled with some compact primes. For most photographers either of these options would probably make more sense; the fp is something of a niche choice.

That said, Sigma has to be applauded for not only trying something different, but also making a first-generation product that realises its concept very well. I’m sure we’ll see the camera’s best new ideas, such as composite low ISO settings and the ability to record directly to SSD, widely copied in the near future. Personally, I really wish the fp had a tilting LCD and some kind of finger grip, but hopefully those will come on a successor model. Even so, it’s an impressive first effort at full-frame from Sigma with its own unique charms.

Sigma fp: Specifications