Thanks to its superior image quality, medium-format photography has traditionally been popular among serious enthusiasts, but the increasing dominance of digital media has resulted in many medium-format cameras now lying idle. Of course, this is great news for the committed film user because it means second-hand medium-format kit has never been so affordable, but the financial and creative freedom of digital photography is just too much to give up for many photographers.

Although the current cost of digital medium-format cameras puts them out of reach of most enthusiast photographers, it’s clear that the format has a future and while more models are being introduced, prices have tumbled over the past few years. With this in mind, Damien Demolder, Angela Nicholson and Richard Sibley set out to discover what can be expected from a current model.

Hasselblad cameras have never been cheap, but they are the benchmark by which others are measured, so the company’s latest model, the H4D-40, is the obvious camera to put through its paces.

This isn’t intended to be a full test, but each of us spent a day shooting a different type of subject with the camera, to see how it handles and performs. We were all keen to find out if Hasselblad’s claim that the H4D-40 is as easy to use as a 35mm SLR really is true, and if any of us would be phoning the bank manager to ask for a loan.

Features

For many photographers the most important fact about the H4D-40 is its asking price, so let’s get it out of the way first. A kit with an 80mm lens can be bought for around £13,000. It is a lot of money, but much less than a digital medium-format setup would have cost a few years ago.

The H4D-40’s modular construction means that, while it is a digital SLR camera, the viewfinder, sensor (or back) and lens can be removed and swapped for alternatives. It also makes the camera more future-proof as the back can be upgraded. In fact, Hasselblad offers two other cameras in the H4D line, among which the only difference in specification is the back. While the H4D-40 has a 40MP sensor, the H4D-50 and H4D-60 have 50MP and 60MP devices respectively.

The Kodak-manufactured sensor in the H4D-40 measures 33.1×44.2mm and has 7303×5478 pixels. Only raw file output is possible (Hasselblad 3FR format) and lossless compression sees the 16-bit files weigh in at around 50MB.

Tethered shooting is possible via a FireWire 800 (or 800 to 400) cable, but as the camera back contains a processing engine and UDMA-compatible CF card slot, the photographer can shoot without connecting the camera to a computer. However, like many medium-format models, the H4D-40 isn’t designed for quick-fire photography: each capture takes 1.1secs. Low-light shooting is also restricted, as the camera has a maximum sensitivity setting of ISO 1600.

The H4D-40 has one cross-type AF point, and features Hasselblad’s innovative True Focus system. This uses level sensors to detect the angle the camera is held at and automatically adjusts the focus to compensate for changes in subject distance when focusing and recomposing.

The 3in LCD screen is not Live View-enabled so images may only be reviewed and not composed on it. It also has quite low resolution with just 230,400 pixels.

The HVD 90x eye-level viewfinder with -5 to +3.5 dioptre adjustment is supplied, but a surprise inclusion, perhaps, is an integral flash (GN 12m @ ISO 100) in addition to the hotshoe.

While it may not have all the technology of a modern APS-C-format DSLR, the H4D-40 has all the modern essentials covered with autofocus, metering and automatic, semi-automatic and manual exposure modes.

Hasselblad H system

The Hasselblad H4D-40 is part of the Hasselblad modular H series of medium-format cameras. Like other digital medium-format cameras, there are two main parts: the camera, in this case with a battery forming the grip, a viewfinder and lens; and the digital back that contains the sensor.

The digital backs are interchangeable, but with the cameras costing upwards of £12,000 most photographers are likely to have only one.

There are currently 11 Hasselblad H-series lenses available, including the HCD 35-90mm f/4-5.6  and HC Macro 120mm f/4 lenses we used with the H4D-40. Lenses from the classic Hasselblad V system are also compatible with H-system lenses via an adapter.

and HC Macro 120mm f/4 lenses we used with the H4D-40. Lenses from the classic Hasselblad V system are also compatible with H-system lenses via an adapter.

One of the more interesting accessories in the H system is the HTS 1.5x tilt-and-shift lens adapter. This works with five of the existing H-series lenses, giving them tilt-and-shift capabilities while retaining infinity focus. However, it costs around £3,500, so it is only likely to be of interest to professional users.

There are three viewfinders available in the H system. The HVD 90x and HV 90x are 90° reflex viewfinders with slightly different magnifications. These viewfinders make the H-series cameras handle a lot more like a conventional DSLR. A waist-level finder is also available in the form of the HVM. Like most medium-format waist-level finders, this features a magnified hood to make precise focusing easier.

A medium-format roll-film back is also available in the form of the HM 16-32 and even the HMi 100, which is compatible with Polaroid 100-type instant film. It may seem odd to produce these products on such an advanced digital camera, but specialist film is still used in some advanced medical and scientific applications.

Medium-format options

Digital medium-format capture began with the introduction of sensor-housing backs that were compatible with several existing medium-format camera systems. There are backs with 22-60 million pixels from companies such as Hasselblad, Leaf and Phase One that are designed to be used with modern, updated medium-format cameras such as the Mamiya RZ67 Pro IID, Mamiya 645 AFD and Hasselblad V-series models available today. Using a back isn’t a cheap option as they generally start at around £7,000.

While these backs were originally  intended to allow photographers to turn their expensive (and much-loved) cameras into digital models, some manufacturers have turned their attention towards producing complete digital systems designed from the ground up.

intended to allow photographers to turn their expensive (and much-loved) cameras into digital models, some manufacturers have turned their attention towards producing complete digital systems designed from the ground up.

In addition to the H4D range from Hasselblad, there are models available from Leica (S2), Mamiya (RZ33), Phase One (645DF) and (hopefully soon in the UK) Pentax (645D).

While none of these cameras is exactly cheap, they generally cost less than buying a camera with a separate digital back.

Landscape Shoot

In the pre-dawn landscape Damien Demolder was glad he had spent some time familiarising himself with the H4D-40’s control layout

My task for this feature was to use the Hasselblad H4D-40 to shoot landscapes. Choosing to shoot just before sunrise and into the morning, I set myself up with the tripod kit, some ND grads and a polariser as one would normally.

The first challenge, though, was the size of the front element of the lenses we were using. With a thread diameter of 95mm for the 35-90mm f/4-5.6 zoom lens and 67mm for the 120mm f/4 macro optic, I was going to have to dig out my largest accessories. The zoom lens barrel is wider than anything else I use, including my plate and 5x4in kit, while most of my medium-format lenses happily share filters with the lenses for my 35mm and DSLR kits.

Packed into a Billingham shoulder bag, the body plus two lenses kit is heavy enough but not much worse than I would normally carry, although all the padding and compartments had to come out so the body would fit with a lens attached.

I used a standard mid-weight Benbo tripod with the Manfrotto 410 geared head, and found both coped well with the load.

Image: Medium format allows extremely narrow depth of field to be used even at ‘quality-safe’ apertures in the middle of the f-stop range

Landscape Shoot Handling

I had spent some time familiarising myself with the menu system and function locations of the camera and back so I would be ready to shoot fluidly in the field.

I am glad I did, as the ‘pushing porridge’ process of moving between features would have been too frustrating to learn on the job. Being used to instant reactions, and buttons and dials with a positive response, I stepped back at least eight years to buttons that require domination to activate and a menu system that hides its features. It is an amazingly old-fashioned and slow system.

In the dark of the pre-dawn the viewfinder of the H4D-40 is bright enough that you can easily check the focus point found by the AF system, and then adjust it if needed.

I found that the camera focuses surprisingly easily on distant subjects and, with their bright wide apertures, the lenses I used made clear what would and wouldn’t appear sharp. The depth of field button takes time to find, but it provides what it should. Neutral density graduated filters are so much easier to use through a large finder.

The screen on the rear of the camera is good enough to let you know you have recorded an image, but it falls some way short of indicating whether the exposure is anywhere near correct, whether you have chosen a suitable colour temperature and whether your focus is accurate. I ran the whole day with the histogram display as reassuring company.

Although, theoretically, the magic of digital imaging means there is no restriction on the number of pictures one can record in a session, CompactFlash cards only hold so much. With file sizes of about 50MB, for now at least we might be almost as restricted as we were with 120 film.

Landscape Shoot Image Quality

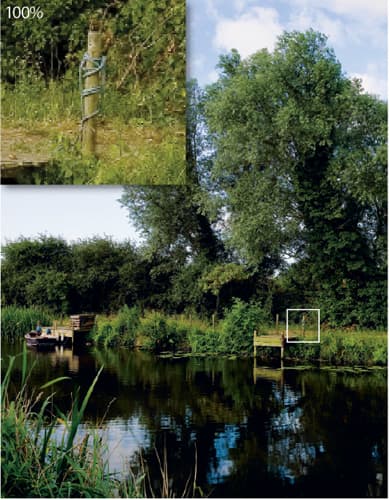

Image: The camera and back combination is able to record such a mass of detail and information that images can be used far in excess of normal enlargement limitations

The handling of the camera, and particularly the back, may not be ideal, but the quality of images produced is first rate.

Shooting between ISO 100 and 800, I found noise is simply not an issue. The lenses and back combine to collect the tiniest detail in the most distant subject, and my landscapes contain every leaf on the trees and every blade of grass.

My usual rule is that you need 300 pixels for every inch of paper you want to print on. With a good camera you can get away with halving that figure, to create a print twice the length, if you first interpolate the file to fill the gaps between the original pixels. Viewing files from the H4D-40 on-screen at 100%, the images look clean and detailed, as though they can be printed at that size. Only when blown up to 200% does the detail become confused and the pixel elements visible. I guess this is what you pay for – the detail and the enlargement potential that good-quality pixels offer.

All images are saved as raw files, and I used the supplied Phocus software to work on the images and then convert them to a more usable format.

Although the software is less convenient to use than the latest version of Adobe Camera Raw, it does have the benefit of customised optical corrections for the lens used, and the focus point and focal length it was used at. In fact, the package is efficient enough, and provides an excellent collection of adjustment possibilities.

The dynamic range achievable gives contrast control right back to the photographer and, although ND grads will still be needed, they will be less necessary than you might be used to.

Landscape Shoot Conclusion

While it is definitely true to say that the pictures produced by the Hasselblad H4D-40 are excellent, it is a little more difficult to say the same of the camera. There are elements that are nice to use, and the metering, colour and viewfinder are all very good.

I do find it hard to get over the handling issues, though, and think the Hasselblad needs to step forward a little to make the menus more usable and the screen of more use. Pentax is streets ahead in this area with its 645D.

We don’t usually comment on value for money, but when so much money is involved it is hard to ignore. The kit I was using would cost £22,424.89, which perhaps is less money for a business tool than it is for a hobby camera. The Hasselblad H4D is not any more expensive than its competition, but for the money I really would expect a better handling experience.

Studio Portraits Shoot

Professional fashion and portrait photography is one of the few realms where the medium-format camera is still king. Richard Sibley tries out the Hasselblad H4D-40 in a studio environment

One of the main reasons for the continued popularity of medium-format cameras among professional studio photographers is the high resolution of images that are captured. For a professional photographer this is vitally important, as the client may wish to make large prints at a high resolution.

It has been a couple of years since I used a medium-format camera, a Bronica ETRS, in a studio, and one of the first things that struck me about the Hasselblad H4D-40 was its size, especially with the 35-90mm f/4-5.6 lens attached. I was a little concerned about camera shake while handholding the camera. I was also slightly concerned that my arms might not be able to keep holding the camera while shooting for a couple of hours.

My fears were largely unfounded. While the camera is more substantial than a professional DSLR such as a Nikon D3X, it is surprisingly comfortable to handhold.

I needn’t have worried about camera shake, either. By turning off the lights for the studio and selecting a shutter speed of 1/250sec, the dim ambient light wasn’t captured by the sensor, leaving the quick burst of the studio flash lights as the sole source of illumination.

Studio Portraits Shoot Handling and Lightroom

It took some time to get used to a few of the H4D-40’s controls, as they are scattered around the side as well as the rear of the camera body. One button that is a little awkward is the True Focus AF button.

Its peculiar position requires you to stretch the thumb of your right hand.

It would be better placed nearer to the thumb’s natural resting place on the rear of the camera. Thankfully, nearly all the exposure-setting buttons are positioned around the H4D-40’s LCD top-plate.

When focusing on the subject’s eye, the extremely shallow depth of field sometimes makes it difficult to tell whether or not the True Focus AF has worked.

Often the pupil would be perfectly in focus, and at other times the eyelashes would be a sharper.

What is staggering is the sheer level of detail that is captured. Again, this is most noticeable in the subject’s eyes. With a 40-million-pixel image, the level of detail can be quite unforgiving – each eyelash and hair is clearly visible, making it a retoucher’s dream, or worst nightmare depending on how you wish to look at the images.

Images: The H4D-40 is capable of capturing a great amount of detail, which is further emphasised by the very shallow depth of field that can be created

Traffic Lights and Lightroom

Before importing the images into Lightroom 3, I used three ‘traffic- light’ buttons on the camera back to tag each image.

Once I had done this I was able to delete all the ‘red’, rejected images from the card, leaving only the green and amber images to be imported into Lightroom. Rejecting the images that weren’t needed at this stage helped to speed up the import process.

With such large file sizes I set Lightroom to create its own full-size preview files when importing the images., which saved time when browsing and cataloguing the images. Also impressive was Lightroom’s default sharpening, which I tweaked to reveal an amazing amount of detail.

Studio Portraits Shoot Conclusion

The H4D-40 is quite a staggering camera and yes, I do want one – I think most portrait photographers would. However, the expense does not make it a viable option for anyone except advertising photographers at the very top of their game. For the rest of us mere mortals there are now plenty of other full-frame, high-resolution DSLRs that will happily fulfil our needs.

Still Life Shoot

Angela Nicholson spent a day shooting still life and macro subjects with the H4D-40, and found herself wishing it was Live View-enabled

I opted to shoot still-life and macro subjects, which meant that the camera would be tripod-mounted throughout. This was a bonus for me: while the H4D-40’s battery creates a comfortable, ergonomically shaped grip, I find that with the 120mm f/4 macro lens mounted, the camera is too heavy to hold steadily to my eye for more than a few seconds at a time.

In the relatively low light of my naturally lit dining room, the H4D-40’s AF system struggled to focus consistently on the close-to dark cherries I selected to shoot. Fortunately, the HVD 90x viewfinder that is supplied in the kit provides a reasonably clear view of the subject.

As I was shooting at about waist-height, the optional waist-level finder might have been easier on my neck – but of course it is less than ideal with portrait-format images. There were also a few occasions when I found I needed a torch to provide a little extra illumination and I had to adjust the lens slightly in and out of focus to gradually find the sharpest point. It wasn’t long before I was longing for Live View technology; the magnified view of the subject would enable me to focus much quicker and more confidently.

Still Life Shoot Mirror-slap

A quick look at my first few images confirmed my suspicions that the hefty clack of the mirror was introducing some shake and that mirror lock-up was required.

Although I had located the appropriate button for this feature, I had to check the manual to fathom out exactly how to use it. It turned out to be quite versatile and I set the camera to lift the mirror two seconds after I pressed the shutter release, then pause for a further two seconds before firing the shutter.

The result was blur-free images. My only frustration was that it doesn’t appear to be possible to set the camera to remain in this mode and the Enter (ISO/WB) and Save (AF) buttons need to be pressed between each exposure.

Still Life Shoot Image transfer

Adobe doesn’t list the H4D-40 as being compatible with Camera Raw 5.7, but I found I was able to open and adjust the 3FR-format images successfully by right-clicking and selecting Open in Camera Raw.

Having a CF card on board means I was free to shoot without computer connection, but the 50MB files soon mount up so transferring the images to a computer can take a while. If you only have a USB 2.0 card reader, it’s worth connecting the camera via the supplied FireWire cable to speed up the process of downloading images.

Shooting with the camera tethered to a computer via the FireWire 800 cable and using the supplied Phocus software means the images are transferred one at a time as they are shot, which could be preferable when shooting indoors.

This method also brings the advantage of allowing each image to be examined in detail on a large computer monitor, as the 3in, 230,400-pixel LCD screen doesn’t display as much detail as some smaller format DSLR monitors. The software can also be used to control the camera, even setting the white balance by using the sample tool to correct an otherwise neutral area.

I shot with the camera untethered for most of the time I had it, and it took me a while to work out how to set a custom white balance because the camera’s two LCD screens display slightly different menus for some features.

Although the white balance button is next to the grip-based LCD, it is impossible to set a custom white balance value via this menu display. I had already used Adobe Camera Raw 5.7 to assess the appropriate colour temperature to set the manual white balance value to, when I discovered a method of setting a custom value via the controls shown on larger LCD screen.

Still Life Shoot Conclusion

Like many photographers, when I use a film medium-format camera I tend to shoot in a slower, more considered way.

To a large extent this is because of the cost of the film and processing and the limited number of shots that fit on each roll, but the size of the camera and the format have an impact as well. During the course of my time with the H4D-40 I shot many more images than I ever have with a film medium-format camera in a single day.

Using a camera that produces 50MB images naturally slows things down a little, but I can see that in the future the jump between a smaller-format digital camera and medium-format model could be made as easy as swapping between an APS-C camera and a full-frame DSLR.

As the H4D-40 stands, I find controlling it via the Phocus software more straightforward than using its own button and dial controls.

Images: Because of the large sensor, depth of field is very restricted with the 120mm f/4 macro lens at f/11 and f/16