Fujifilm GFX100: At a glance:

- £9,999 body-only

- 102MP medium-format BSI-CMOS sensor

- ISO 100-12,800 standard, ISO 50-102,400 extended

- 5 frames per second shooting

- 5.76-million-dot EVF

- 2.36-million-dot tilting touchscreen

When Fujifilm decided to give full-frame a miss and instead develop a medium-format mirrorless system, it offered a perfectly rational explanation. Its APS-C X system would comfortably meet the needs of the vast majority of enthusiasts, especially given its comprehensive system of matched lenses. But for professionals requiring higher image quality, the larger 44x33mm sensor would provide a much more significant step up compared to full-frame. However, while the firm’s current 50MP GFX cameras are capable of producing truly stunning images, the problem is that high-resolution full-framers such as the Nikon Z 7, Panasonic Lumix S1R and Sony Alpha 7R III aren’t all that far behind, while offering faster and more polished operation.

With the GFX100, Fujifilm’s answer has been to boost the resolution to a spectacular 102 million pixels, comfortably surpassing any of those rivals. Its brand-new back-illuminated sensor also gains on-chip phase detection, promising much faster autofocus – arguably the biggest drawback of the firm’s existing models. To further increase its all-round appeal, the camera boasts in-body image stabilisation (IBIS) and 4K video recording. However, the cost of all this technology is a significantly higher price: the GFX100 will set you back twice as much as the SLR-shaped GFX 50S, and almost triple the more compact, flat-bodied GFX 50R. But in context, that’s still only a third of the price of its ultra-high-resolution rivals from the likes of Phase One and Hasselblad.

Of course, I doubt many of our readers are likely to buy a 102MP camera that costs £9,999 body-only. But for a one-off special occasion, it won’t necessarily be out of the question to hire one. And if nothing else, it’s a really interesting demonstration of what’s possible at the cutting edge of camera technology, perhaps giving some clues as to what we’ll see in more mainstream models in the not-too-distant future.

Fujifilm GFX100 – Features

First of all, let’s think about what 102MP really means. The GFX100 outputs files that measure 11648 x 8736 pixels, which equates to approximately 39 x 29 at an output resolution of 300ppi (for metric thinkers, that’s about a metre wide). As a result, it can deliver critically sharp prints about four times the area of A3+, the largest paper size home printers can generally handle. Even its full-frame crop mode delivers 9552 x 6368 pixel, 60.8 MP images – fractionally larger than the new Sony Alpha 7R IV. It’s a landscape photographer’s dream.

While the GFX100 isn’t the first 100MP medium-format camera ever made, it is the first that’s been specifically designed for hand-held shooting under demanding outdoor conditions. With such a high-resolution sensor, even the slightest handshake or operational vibration risks blurring fine detail. So Fujifilm has gone out if its way to help users get the full benefit of its resolution without having to use a tripod all the time.

Accordingly, the GFX100 is the first medium-format camera to include in-body image stabilisation (IBIS), that’s claimed to provide up to 5.5 stops of shake reduction. The firm has also isolated the shutter from the sensor, IS unit and lens mount using a system of springs, to minimise any chance of image blurring from mechanical shock. By default the camera uses an electronic first-curtain shutter to eliminate vibration, although a mechanical first curtain is required at shutter speeds faster than 1/1250sec.

In terms of core photographic specifications, the standard sensitivity range covers ISO 100-12,800, with extended settings reaching ISO 50-102,400. While this is vastly beyond the range offered by older medium format sensors, it’s still not quite a match for the best full-frame models. However Fujifilm claims that the new back-illuminated sensor can record a very impressive 14 stops of dynamic range, with a 16-bit raw option available to make the most of this.

The resultant raw files are vast, at 200MB a shot, which means they require an up-to-date computer to process them at anything like a sensible speed. Even using a brand-new top-spec Windows laptop with an Intel Core i9 processor, they take about 10 seconds each to develop; on a 5-year-old Core i3 machine they can take almost a minute. Then there’s the disk space required simply to store all this data.

The camera offers timed shutter speeds as slow as an hour, which means that landscape photographers shooting with deep neutral density filters shouldn’t have to mess around with bulb mode. The mechanical shutter maxes out at 1/4000sec, and while the silent fully-electronic shutter can attain higher speeds up to 1/16000sec, it’s generally best avoided as rolling-shutter distortion is immense.

Continuous shooting is available at 5 frames per second, which again doesn’t match the latest high-resolution full-frame cameras, but is still pretty staggering when you consider the data throughput. However once you get past the spec sheet and actually use the camera, it quickly becomes apparent that live view between frames isn’t available at this speed, with the camera playing back previous images instead – something most mirrorless cameras grew out of about five years ago. If you want to keep track of moving subjects in the viewfinder, you’ll have to drop down to the 2 fps Continuous Low mode. So not surprisingly, this really isn’t a sports and action camera.

Elsewhere you get broadly the feature set as Fujifilm’s X-system users have come to appreciate. Most importantly, this includes the firm’s Film Simulation modes, which surely count as the most attractive suite of colour and black & white JPEG processing modes you’ll find. In-camera raw processing allows you to experiment with different looks after shooting, too. Given that the ludicrous resolution will reveal every tiny detail, whether you like it or not, Fujifilm has included a new ‘smooth skin effect’ option for portraits. Other handy features include an intervalometer and extensive bracketing options.

The integrated grip has allowed Fujifilm to include two NP-T125 batteries, as previously used in the GFX 50S and 50R, promising a combined endurance of 800 shots. As befits a professional camera, the GFX100 also has dual high-speed UHS-II SD card slots. It’s possible to use them simultaneously or sequentially, or record JPEGs to one and raw files to the other. On the left side you’ll find microphone and headphone sockets, along with USB-C, HDMI and 15V power-in connectors, plus a PC sync socket for studio flash. A 2.5mm remote control socket is located on the handgrip.

The GFX100 also boasts an extremely impressive video specification. 4K recording is available at 30fps using the full width of the sensor, with footage recorded at 10bit 4:2:2 externally and 10bit 4:2:0 internally, using the H.265/HEVC codec. Fujifilm has included its cine-optimised Eterna Film Simulation mode, while F-log allows greater flexibility for grading in post-production. Hybrid Log Gamma is also available for recording HDR footage.

Naturally Wi-Fi and Bluetooth are built-in, allowing connection to a smartphone or tablet for remote control of the camera or copying images for sharing. Meanwhile tethered shooting is available via the USB-C port, using Fujifilm X Acquire or Capture One Pro software.

Fujifilm GFX100 – Build and handling

In terms of design, the GFX100 resembles a pro-level full-frame SDLR, with an integrated vertical grip to accommodate a pair of hefty MP-T125 batteries, and a duplicate set of controls for portrait-format shooting At 156.2 x 163.6mm x 102.9mm and 1400g in weight (including both batteries), it’s very similar in size to the full-frame Nikon D5 or Canon EOS-1D X Mark II. With two separate magnesium alloy shells, one for the outer body and another to protect the core imaging components inside, it’s also built to withstand tough conditions, being dust- and water-resistant and freeze-proof to -10 °C. This all makes it much more robust and easier to handle than conventional medium-format DSLRs.

Strikingly, the GFX 100 does away with the analogue shutter speed and exposure compensation dials that are a hallmark of Fujifilm’s other cameras. Instead it employs pairs of electronic dials on each grip to control shutter speed, ISO and exposure compensation, with the aperture set using a ring on the lens. There’s no conventional exposure mode dial: when the aperture ring is set to its A position, a button beside the top LCD cycles between shutter priority and program modes; otherwise it toggles between aperture priority and manual. Holding this button down for a couple of seconds also locks the shutter speed. A large dial on the top-plate switches between stills and video modes, allowing optimised settings to be retained for each.

The rear LCD is touch-sensitive, which can be useful for setting the focus point and browsing through images, and in particular for operating the onscreen Q menu. However it’s a touch laggy, and can’t be used to navigate the main menus. So while it’s nice to have, it’s not as useful as those we’ve seen on recent high-resolution full-frame models such as the Panasonic S1R and Nikon Z7.

The LCD is touch sensitive, which is great for positioning the focus point or changing settings via the onscreen Q Menu.

Fujifilm has, however, made some uncharacteristic errors with regards to the handling. The control dials, buttons and joysticks are all tiny, and very difficult to operate with gloves. The main grip is nicely sculpted with a thick rubber coating, but the vertical grip is just a slim slab of bare metal, making it distinctly uncomfortable to hold. The control layout is also inconsistent between the two grips, with the exposure compensation and AE-L buttons in different places; this is compounded by the fact that so many of the buttons are unlabelled. Meanwhile the portrait grip AF-selection joystick is difficult to locate as it’s recessed behind a ridge on the back. This really shouldn’t be the case on a professional camera costing £10k.

Unfortunately the portrait grip is awful, with no rubberised coating and a different layout to the main grip

However there’s plenty of customisation on offer, and with a little tweaking the camera’s most egregious handling flaws can be mitigated. Most importantly, setting the exposure compensation button mode to Switch means that the rear dial continues to operate this setting until you disable it again, regardless of whether you turn the camera on or off. Even at its best, though, the GFX100 doesn’t really handle how a professional camera should. This stands in stark contrast to the similarly-shaped Olympus OM-D E-M1X, which works like a dream, with large easy-to-use controls and a vertical grip that closely mirrors the main one. But the GFX100 has a sensor that’s more than six times as large, so the image quality is incomparable.

Fujifilm GFX100 – Viewfinder and screen

If there’s one area where the GFX100 can’t be criticised, it’s when it comes to viewing your images. The camera employs a simply stunning electronic viewfinder, with a huge 5.76-million-dot resolution and 0.86x magnification that provides a vast, detailed preview image. Multiple viewing modes are available (which Fujifilm confusingly calls Boost modes), depending on whether you want to prioritise resolution, frame-rate, or autofocus speed. The differences may not be easy to see at first, but they genuinely make a difference to how the camera and viewfinder perform. As on the GFX 50S, the EVF unit is removable, with an optional hinged adapter that can be placed between it and the body if you wish to shoot at different angles.

A huge array of exposure information can be overlaid on the live view feed, including gridlines, an electronic level, a live histogram and a focus-distance scale. The exposure is always previewed live, which helps you judge exposure and avoid clipping highlights, while a half-press of the shutter previews depth-of-field. By default the in-camera processing is also previewed, but if you’re shooting in high-contrast light this can cause the shadows to block up excessively, hindering composition. In such situations I generally preferred to use the Natural Live View setting, which aims to replicate the look of an optical viewfinder by lowering the contrast and displaying more neutral colours.

On the back, there’s a 2.36-million-dot 3.2in touchscreen with a 3-way tilt mechanism that enables waist-level shooting in both portrait and landscape formats. However if you want to shoot with the LCD tilted upwards as a waist-level finder in landscape format, you’ll need to remove the EVF, as it overhangs the back of the camera so far that it blocks most of the screen. This isn’t necessarily a problem if you’re shooting static subjects such as landscapes, but it’s infuriating when you’re trying to work quickly. Swiping up or down on the touchscreen overlays a large YRGB histogram or a larger and more precise dual-axis electronic level. These displays can be particularly handy when you’re setting-up shots precisely on a tripod.

Like on other high-end Fujifilm models, the LCD can be used as a low-angle finder for portrait-format shooting

Additional monochrome status displays are found on the top and back. The large top-plate LCD screen can show detailed exposure information, a virtual ISO / shutter speed dial display or a live histogram, which can be handy for judging exposure when the camera is on a tripod. Meanwhile the small rear sub-monitor screen below the main LCD can show a brief summary of camera settings, exposure information, or a live histogram. But while it’s easy to cycle through display modes on the top screen by pressing a small button alongside, you have to dive into the menus to change the rear display, which makes it less useful than it should be. It would be nice to be able to access this from a function button or the Q Menu.

Fujifilm GFX100 – Autofocus

Until now, medium format cameras have always been known for sluggish autofocus performance. But the GFX100 is different, because it’s the first to employ on-sensor phase detection, using 3.76-million PDAF pixels that are spread across the entire image area. The improvement this brings over its 50MP siblings that use contrast detection is huge, with dramatically faster AF along with enhanced face- and eye-detection.

While it would be an exaggeration to claim that the GFX100 can match the very best AF systems around, it’s certainly quick enough to keep up with the camera’s likely uses. One word of warning for existing Fujifilm GFX users, though: all GF lenses require a firmware update to work with PDAF, and it increases their speed significantly.

The GFX100 focuses quickly and perfectly accurately even on off-centre subjects. GF 120mm F4 Macro, 1/160sec at f/4, ISO 400. Thanks to TimeLine Events, model: Yasmin

For static subjects the GFX100 behaves like any modern mirrorless, focusing near-instantly, quietly, and unerringly accurately, no matter where the subject is placed within the frame. With moving subjects it works surprisingly well too, thanks to the use of tracking algorithms borrowed from the firm’s top-end X-system cameras. Again, this isn’t a sports camera, but it’s perfectly capable of keeping focus on models walking towards you, for example. Face and eye detection works pretty well too, and I got good results using it at a vintage portrait shoot organised by Timeline Events. But it’s far too easy to turn off by accident, as the buttons that activate it are very exposed on the corners of the camera.

Fujifilm GFX100 – Performance

After a couple of weeks shooting with the GFX100, what’s impressed me most is how little it feels like a medium-format camera. Obviously it’s not as blisteringly quick as Canon and Nikon’s similarly-sized pro sports models, but it’s more than fast enough for the majority of subjects. It’s also unexpectedly easy to use.

The GFX100 delivers ground-breaking mage quality for its price, while being easy to use. GF32-64mm F4 at 53.6mm, 1/180sec at f/8, ISO 200

Previously, I’ve got used to writing about how you need impeccable photographic technique to make the best use of high-resolution cameras. But with its PDAF, IBIS and vibration-free shutter, the GFX100 makes it implausibly simple to get sharp, blur-free images time after time while shooting hand-held. This brings far more fluidity and mobility to your photography, which can be invaluable when you have a brief window of stunning light to exploit, for example.

Of course, a high-resolution sensor is nothing without a decent lens in front of it, and special mention has to be made of Fujifilm’s supreme optics. I used the GFX100 with the GF110mm F2 R WR portrait lens, the GF120mm F4 Macro R LM OIS WR, and the GF 32-64mm F4 R LM WR wideangle zoom, which are all practically flawless. Indeed the latter might just be the finest zoom I’ve ever used, and capable of rendering fine details right into the corners of the frame, even when viewing files close-up onscreen.

100% crop from bottom right corner

The image of Mount Fuji above was shot with the GF 1o0mm F2 R LM WR, and to get an idea of just how much detail is recorded in the foreground trees, here’s a 100% crop. This may not look like anything much different to other cameras, until you realise that when viewed on a standard 96dpi monitor, this is akin to staring up-close at a print somewhere around 3 metres wide. Oh and it’s taken from the extreme bottom right corner of the frame.

Here’s another example of the GFX100’s stunning resolution. This is an extreme crop of a lucky snap of a honey bee, taken with the 120mm f/4 macro. It would happily print to 10 x 8 inches, despite representing only about 7% of the overall image area.

The GFX100 gives astonishing image quality, with immense levels of detail and vast dynamic range. GF 32-64mm F4 at 32mm, 1/240sec at f/8, ISO 200

Metering is generally very accurate, and it’s easy to see in the viewfinder when you’re in danger of either clipping highlights or underexposing, and adjust accordingly. Aside from the sensor’s staggering levels of detail, it also records vast dynamic range, giving you scope to expose for the highlights even in extremely high-contrast situations, then simply bring up the shadows in raw processing. At low ISO settings the GFX100 gives results that comfortably surpass even the best full-frame cameras, as well as its current 50MP GFX models.

High-ISO image quality is very good indeed. GF 120mm F4 macro, 1/200 sec at f/4, ISO 8000. Thanks to TimeLine Events, model: Charlotte

The sensor is no slouch at high ISOs either, and a big advance on the older 50MP cameras; I’d have no hesitation in selecting its highest standard ISO 12,800 setting when necessary. The in-body IS also works very well, and means you don’t have to worry about keeping shutter speeds high simply to avoid camera shake. However if you’re doing a lot of low-light shooting a full-frame system would probably make more sense, due to the widespread availability of high-quality fast primes.

Here the IBIS allowed me to stop down for depth-of-field while shooting hand-held. GF32-64mm F4 at 32mm, 1/4 sec at f/16, ISO 100

Fujifilm’s in-camera colour processing is peerless, with a whole suite of attractive film simulation modes to choose from. For colour I tend to prefer Astia, or ProNegS for portraits, while Acros delivers wonderful black & white images. Unfortunately Adobe software doesn’t yet replicate these profiles, but it’s sure to sooner rather than later. Auto white balance is pretty much perfect, and I rarely felt the need to diverge far from the camera’s judgement when processing raw files.

Fujifilm’s ProNegS mode gives a wonderfully natural-looking colour palette to this portrait, complemented by smooth skin effect processing. GF110mm F4 Macro, 1/150sec at f/4, ISO 400. Thanks to TimeLine Events, model: Yasmin

Portrait photographers should certainly appreciate the Smooth Skin Effect setting, which essentially lowers the contrast of moderately fine detail to give a more flattering complexion (rather like setting the new Texture slider in Lightroom to a negative value). Just be aware that this affects every tone in the image, not just skin, so landscape photographers (for example) will want to turn it off.

We’d like to thank TimeLine Events for setting up the portrait samples used in this review.

Fujifilm GFX100 – Image quality

Thanks to its 102-million-pixel medium-format sensor, the GFX100 comprehensively outperforms any other camera we’ve tested to date. As expected it offers considerably higher resolution than any full-frame model, aided by Fujifilm’s exceptionally sharp GF lenses. At high ISO settings it also clearly outperforms its 50MP medium-format cousins, particularly when its higher resolution is taken into account.

Fujifilm’s excellent in-camera processing gives superb JPEGs direct from the camera, but as always you’ll only be able to fully exploit the sensor’s astonishing dynamic range by shooting raw.

Fujifilm GFX100 – Resolution

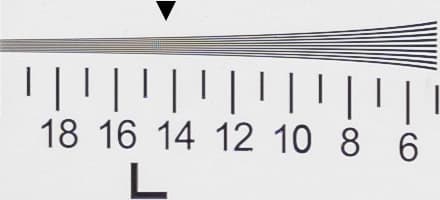

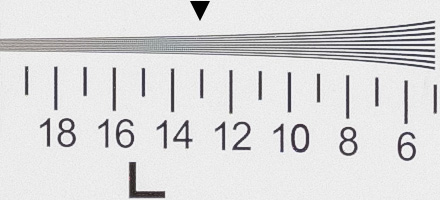

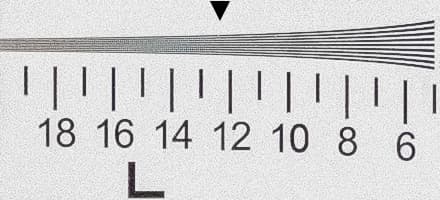

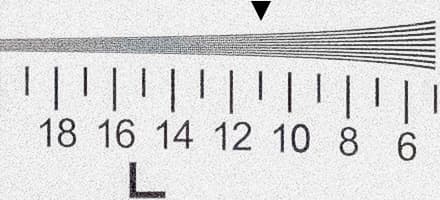

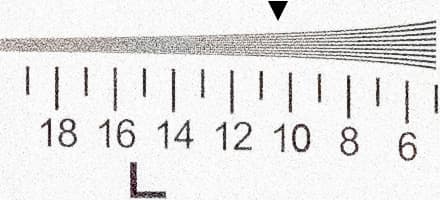

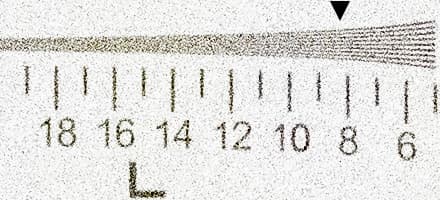

At its base ISO 100 setting, the GFX100 resolves approximately 8,500 lines per picture height in our resolution chart tests, comfortably surpassing even the best full-frame models. This declines gradually as the sensitivity is raised, with over 7,800 l/ph still achieved at ISO 800, and 7,400 l/ph at ISO 3200. Beyond this things fall apart much more rapidly, and by ISO 12,800 resolution has dropped to 6,600 l/ph. The extended settings decline especially rapidly, and at the top setting of ISO 102,400 resolution drops down to about 4,900 l/ph. But in context, that surpasses the best that can be achieved by 24MP cameras. In the crops from our resolution chart below, multiply the numbers beneath the lines by 600 to calculate the resolution in lines per picture height.

Fujifilm GFX100, raw, resolution at ISO 100

Fujifilm GFX100, raw, resolution at ISO 800

Fujifilm GFX100, raw, resolution at ISO 3200

Fujifilm GFX100, raw, resolution at ISO 12800

Fujifilm GFX100, raw, resolution at ISO 25600

Fujifilm GFX100, raw, resolution at ISO 102400

Fujifilm GFX100 – ISO and noise

It should come as no surprise to hear that the GFX100 extracts a ridiculous amount of detail from our standard test scene. There’s barely any visible difference in image quality from ISO 50 to ISO 400, and it’s only at ISO 800 that we start to see the slightest hint of pixel-level blurring, which is most unlikely to be perceptible in print, even at 1m wide. By ISO 3200 image degradation is more obvious, with almost all really fine detail blurred away and general a drop in local contrast. But then again, you have so many pixels to play with that even ISO 12800 should give perfectly acceptable-looking A3 prints. However noise has a significant impact on the extended ISO settings, and I’d steer clear of anything above ISO 25,600.

Below are 100% crops from our standard test scene, processed using Adobe Camera Raw. Just bear in mind that on a conventional monitor this is akin to staring closely at prints 3 metres wide.

Fujifilm GFX100, raw ISO 50

RAW ISO 400

RAW ISO 3200

RAW ISO 12800

Raw ISO 25600

Raw ISO 102400

Fujifilm GFX100 – Verdict

It’s easy for us to get blasé about all the new cameras that pass through the AP office. While they’re constantly improving, they don’t often bring something completely new to the table. However, just occasionally one comes along that offers a step-change in capability, and the GFX100 is a perfect example. It completely redefines what’s possible in a sub-£10,000 camera.

It’s not just the jaw-dropping image quality that matters here, although the resolution and dynamic range are unparalleled for a camera of this size or price. It’s also the ease with which you can take full advantage of that astonishing sensor. Shooting with the GFX100 and getting high-quality 102MP files is really no more difficult than using one of Fujifilm’s APS-C X-system models.

Indeed where ultra-high-resolution medium format was once the preserve of the studio, the GFX100 is perfectly home on location. It’s not excessively large or heavy and is easy to shoot hand-held, while the autofocus is strikingly quicker than the current GFX 50R and 50S models. Landscape photographers should find it perfectly realistic to trek a couple of miles carrying the body and two or three lenses in a backpack.

The camera’s biggest drawbacks relate to handling, and specifically the tiny controls, mismatched grip layouts and uncomfortable portrait grip, which fall well short of what we’d expect from a £10,000 professional model. But these flaws become more forgivable when you look at the extraordinary output. This is a niche camera for sure, but for photographers craving the maximum possible detail without sacrificing mobility, it’s an absolute revelation.