In partnership with Nikon

Your guide: Jeremy Walker

For more than 25 years, Jeremy Walker has been producing landscape, architectural and urban images for use by advertising agencies, design clients and publishers. Not only does he lead LEE Filters workshops, but he also runs his own workshops in the UK and overseas. See his website for more.

Location hunting

Finding locations is easy if you devise a plan of action and put in some legwork

Google it

(Other search engines are available, don’t forget.) Search engines are a powerful tool for research and perhaps the best tool for location hunting. Cross-check your facts, though, because not all of the information on the internet is accurate and up to date – that ruined castle you have seen images of may now be a luxury five-star hotel, so double-check before you go.

Check magazines and books

Many publishers now produce books for location finding

(no doubt there is also an app and tablet version). Split into regions or counties, these books will show an image of the location, but go on to give exact coordinates, parking spots, what time of day or year to shoot, and pretty much where you should put your tripod.

Do it yourself

Check out Ordnance Survey maps (the proper paper ones, not the ones on your phone). Study a map and ask yourself questions about the terrain; look at footpaths and bridleways to see where they lead and what opportunities they may afford. Just because a particular area does not have any images on the web does not mean that it’s a poor area for photography. Don’t be a sheep, be a leader.

Take advantage of local knowledge

Speak to the locals and tell them what you are doing or looking for. Local farmers are a great source of information – after all, they are the ones who are out in all weathers, at all times of the day, so they will know their patch intimately.

Search through websites

Look at the websites of landscape photographers and workshop companies. Many photographers will put the location information alongside their images. Check out their social media feeds and see if they mention the nearest town or landmark. Workshop companies have to advertise where they’re going, so they post images of their tours. Many will mention where they’re staying, too, which provides a clue.

Use social media

Follow the photographers and image makers that you admire. Follow their Facebook posts or their Instagram accounts. All photographers want you to ‘Like’ their images and most seem quite happy to tell you where they are shooting, what they are shooting and where they are heading to next. Be warned, though, some photographers will deliberately mislead and not reveal the exact location of their image. It’s important to do your own research.

Be prepared

Be prepared

Recce your location. Check out weather forecasts, sunrise and sunset times and, if appropriate, tide times. Know how to get back to your car, as paths will look very different in the dark when lit with a head torch. If you have the time, explore your location in advance, even on a grey day when shooting opportunities may be limited. The more you know about your location, the better the chances of securing a great image.

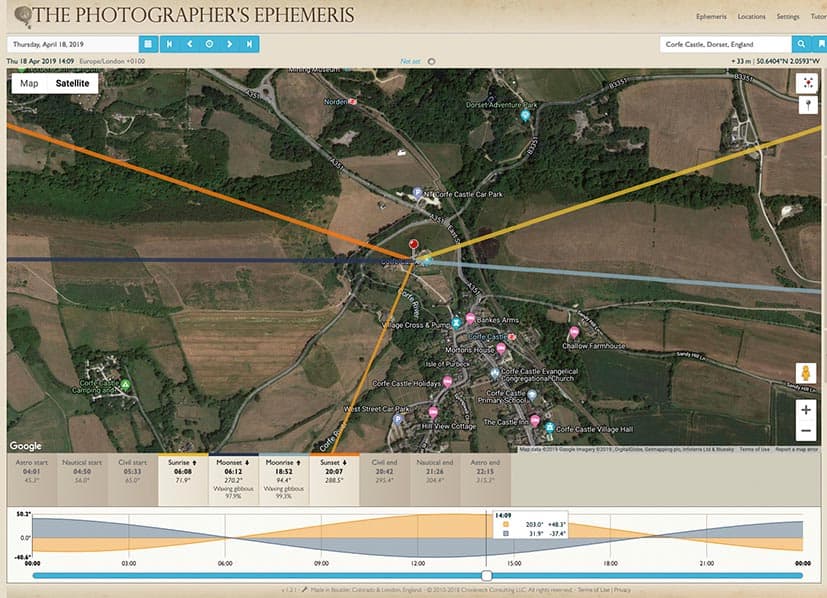

Download an app

There are hundreds of apps for finding locations, and once you have found one there are hundreds more telling you if it will rain, what time the sun will set and in which direction the moon will rise. There really is an app for everything. Probably the most useful is The Photographer’s Ephemeris. Strictly speaking, this is not a location-finding app, but it’s one of the most useful for location photographers.

Kit list

Mobile phone: Make sure your phone is fully charged, and conserve power. If you’re heading to a location with poor reception, check the last place where you had a strong signal just in case you have to make an emergency call.

Ordnance Survey map: Carry an OS map of your location and know how to read it. If you don’t want to carry a bulky map, then before you head out, download the section you need from the internet (try Bing Maps), do an A4 printout, and put it in a waterproof sleeve.

Head torch and whistle: If your phone fails, you can still attract attention in an emergency. Learn the correct sequence of blasts or flashes to aid rescuers. A torch, preferably a head torch, should be carried at all times – you may linger longer than expected and light levels will start to fall.

Your guide: Verity Milligan

Verity is a professional landscape photographer based in Birmingham. She has worked on campaigns for organisations such as Yorkshire Tea and Visit Britain. She’s happiest when outdoors, and relishes the opportunity to connect with people, environments and cities. See here for more.

Crucial composition

Composing eye-catching pictures can sometimes mean breaking the rules

It’s not all about the wide angle

Traditionally, when we consider landscape photography, we automatically think of wideangle lenses. However,

one of my favourite things to do is shoot landscapes with a telephoto lens. Having the reach of a longer lens enables me to go deeper into a scene and explore the smaller details that could otherwise have been missed in a photograph shot with a wider lens. This kind of landscape photography can be difficult to master, but it offers the opportunity to capture a scene from unexplored angles.

Shoot landscapes in portrait

Landscape photographers will often have a wideangle lens in their kit bag. This can encourage the photographer to include as much as possible in the photograph. Shooting landscapes in the portrait format is a great way to focus

the mind on a particular composition and provides an opportunity to really consider what should be in the frame. Shooting landscapes in portrait orientation can be particularly effective if you’ve got a strong foreground and wish to lead the viewer through the scene to the background.

Play with the light

When the sun is low in the sky, it casts a wonderful golden hue across the landscape. Where you position your camera will change how you perceive that light. I don’t often shoot directly into the sun because of the implications of lens flare, and if the sun is behind you it can make the scene quite garish. Ideally, depending on the circumstances, using side light in your composition can be particularly pleasing, especially during dawn and dusk.

Use your mobile to ‘sketch’ a composition

When I’m out in the landscape I’m encumbered with a lot of kit, which can make it difficult to continuously change position. If you’re like me in this way, one trick is to use your smartphone to visualise a composition. Most phone lenses are 21-24mm, so are comparable to a wideangle. The phone gives me freedom to move around in the scene and pinpoint the best composition without struggling with my kit. And while I’m there, I capture the scene on my phone for good measure.

Change your perspective

Photography is a participation activity – you’re not meant to stay in one spot. Changing the perspective by moving the camera up and down can completely transform a composition. Placing the camera close to the ground can provide a completely new perspective on a scene and you might end up seeing a composition that would not be possible if you were shooting from your usual camera position. The same applies to a higher perspective, especially if you’re using a wideangle lens and you’ve got a strong foreground.

The rule of thirds

One of the most basic rules in all of photography, not just landscape, is the rule of thirds. Instinctively, the human eye knows when something looks correct in an image and more so when it doesn’t. The rule of thirds encourages positioning of important elements one third of the way in from the edge of the frame. The more you practise composing this way, the more it becomes second nature and you begin to understand how all the elements should work together in the image.

Break the rules

However, there are certain circumstances when it’s okay to ‘break’ the rule of thirds, particularly if you’re photographing reflections. In this case, it makes more sense (and it’s more pleasing to the eye) to position the horizon in the middle of the image so you can maximise the impact of the reflection. This can be especially effective if you’re capturing a body of water like a lake, canal, or even a puddle!

Leave out the sky

When I first started capturing landscape photographs, I would make sure I had everything in the frame: the foreground, background and the sky. This not only made it a struggle to expose correctly, but it also made my images quite ‘messy’. On workshops, I often give the advice to avoid including the sky in your compositions. This allows you to concentrate on the scene in front of you without the distraction of dealing with the bright highlights that are so often part of the sky.

Kit list

Tripod: My carbon-fibre Gitzo Mountaineer Series 2 is essential. I can trust it to keep my camera steady even

if the conditions are less than ideal.

Filters: I currently shoot with the LEE Filters 100 kit (below). The circular polariser and 0.9 soft ND grad are permanently on the front of my camera.

Lens cleaner: Small, but infinitely useful, especially if I’m shooting in changeable weather or near the coast. Ultimately, clean lenses ensure my images stay sharp.

Your guide: David Clapp

David Clapp is a landscape, architectural and travel photographer. A jack of all trades, he works for Canon UK, is a stock photographer for Getty Images and leads popular photographic tours across the world. David recently received a direct fellowship from the RPS. See his website for more.

Camera settings

Successful landscape photography starts with the right camera settings.

Manual mode

Gain maximum control of your exposures by using manual mode. Although this seems somewhat confusing at first, take time to learn how the change in aperture, shutter speed and ISO affects the exposure. The camera’s in-built metering system can only do so much, so use manual to gain complete control. First, choose the aperture to control depth of field. Second, dial in shutter speed to alter image brightness. Third, adjust your ISO, if you feel your shutter speed is too slow.

Don’t fear high ISO

Many landscape photographers fear using high ISOs, but – with the quality of modern cameras – there has never been a better time to use it. A higher ISO such as 1600 is virtually noise free, even on most consumer cameras, and should be embraced. Shooting landscapes with a long lens can benefit greatly from high ISO, lifting the shutter speed to reduce camera shake. Higher ISO can also be perfect for controlling motion, like water movement in rivers or coastal landscapes.

Mirror lock-up

The one way of ensuring your imagery is as sharp as possible is to use mirror lock-up (with a DSLR). With your camera mounted on a tripod, vibration can be caused not only by wind but also by the mirror movement as it lifts up and down, especially with longer focal lengths. Using this feature alongside a cable release or a two-second timer will ensure the sharpest possible image, as the mirror lifts up, before a delayed shutter fires.

Customise ‘My Menu’

Most cameras have a My Menu feature that allows you to collate all your essential menu items into a list, so you can avoid endless menu searching. Some important ones to include are white balance (if it’s only located in the menu), mirror lock-up for DSLRs, and picture styles (for switching to B&W, for example). I am surprised to see ‘Format Card’ in the My Menu list on many client cameras!

Custom controls

Custom controls are a great way of storing a snapshot of the entire camera’s settings and retrieving them via a quick turn of a dial for handheld landscapes. Many cameras contain as many as three custom settings or more (C1, C2, C3), so store your presets to save you from menu digging. Set C1 to aperture priority, single shot, f/5.6, ISO 200, and daytime white balance. Set C2 to the same, but with ISO 1600 (for darker environments). Then set C3 to the same again, but with low-speed continuous shot and servo focusing, in case something unexpected happens (like a wildlife opportunity).

Ride the colour temperature

Rather than relying on a pre-programmed white balance value (such as sunny or cloudy) to set your white balance, choose the K setting and learn to set your white balance to match the scene you are shooting. Higher values of K warm the scene up, whereas lower values cool your picture. It’s a great idea to match your live-view screen to what you see, as this really helps to provide you with a great starting point when it comes to your processing.

Image stabilisation

Sometimes you need to use all the tools you can get to achieve that sharp shot, so image stabilisation saves you from reaching for the tripod. My record for a pin-sharp handheld shot at 400mm is 1/3sec! Image stabilisation (IS or VR) works by using gyroscopic elements to correct any physical movements, operating a lens element to

move in the opposite way to that direction. When on the move, or in failing light, let IS help you get that successful shot. Leave it switched on all the time, but not when on a tripod, although some professional lenses recommend leaving it switched on.

Change the aspect ratio

Learn to see differently by using the camera in different aspect ratios. The beauty of these modes is that they teach you to spot compositions and encourage a more interesting approach to an image – a bit like choosing different time signatures in music. Most cameras have additional aspect ratios, such as 4:3, 16:9 and my favourite, 1:1. Learning to see square is one of the most powerful lessons and creates a wonderful alternative portfolio. Remember to shoot in raw, as this will ensure you can revert to 3:2 when processing.

Kit list

Really Right Stuff BH-55

There is no ballhead more sturdy or more heavyweight than this one. It’s the most stable of platforms and is essential for my long-lens landscape work.

L-bracket

By keeping the centre of gravity over the centre of the tripod, the L-bracket ensures the most stable of images, whether you are using landscape or portrait orientation.

Levelling base

I’m a panoramaholic, so I use a levelling base (above) – it ensures a flat plane of rotation in one motion, without all the faff of levelling the legs individually.

Your guide: Mark Bauer

Mark Bauer has been a full-time professional landscape photographer since the early 2000s, supplying images for editorial and commercial use to clients around the world. He is the author of six books, and has won a number of awards in major competitions. See his website for more.

Lighting

Reading and understanding natural light is fundamental to landscape photography

Use backlighting for drama

Shooting into the light – especially when the sun is low in the sky – can produce dramatic results, with shadows fanning out towards the camera and emphasis on shape and form. Choose bold, graphic compositions, and if there are strong shapes in the foreground, consider silhouetting them by metering from the bright sky. If you are not aiming to silhouette your subject, keep an eye on the histogram and be prepared to increase exposure, as backlighting can fool meters into underexposing. Flare is also a potential problem, so use your hand to shade your lens from the sun.

Dealing with midday sun

It’s perfectly possible to shoot good landscapes in the less photogenic light of the day. Waiting for the right moment pays dividends. Clouds diffuse harsh sunlight, so shoot when the sun is covered or partially covered. On blustery days when the clouds are moving quickly, there is potential for dramatic light as the sun bursts through and creates a spotlight on the land below. In harsh light, consider shooting monochrome. Contrasty scenes containing deep shadows and bright highlights make good mono conversions with the right subject.

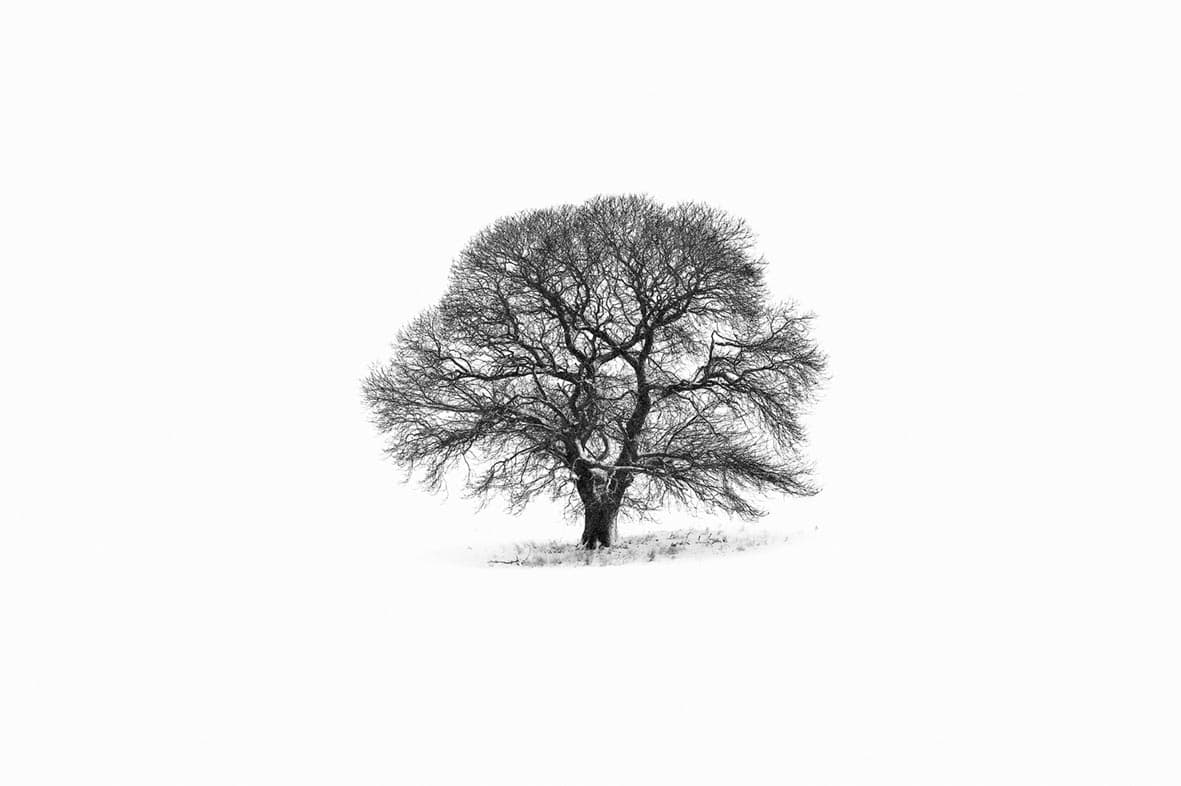

Make the most of dull light

On dull, overcast days, it can be tempting to stay at home and catch up on image processing, or sit on the sofa and read a book. But you’re missing a trick if you don’t head out with the camera, as this type of lighting can be incredibly productive. One option is to pack a set of neutral-density filters and head to the coast to shoot some long exposures. Keep compositions simple and exploit the negative space around your subject. Long-exposure minimalism works best when it highlights the contrast between a static subject and the moving elements around it.

The blue hour

Most photographers pack up as the colour drains from the sky after the golden hour. However, if you like moody, romantic landscapes, then you should stay around for the ‘blue hour’: the period of twilight when the residual sunlight takes on a blue hue. Alternatively, get to dawn shoots early for the morning blue hour. Cityscapes are a natural choice of subject, as the blue backdrop contrasts with artificial lighting. With rural landscapes, look for water as reflections make great foreground interest.

Transitional light

The most dramatic lighting for landscapes usually happens during the transition from one state to another – light to dark or vice versa, the transition from one season to another or as one weather front replaces another. Showery days are one of the best examples of this: as a shower passes and the sun breaks through, the light is dramatic with amazing clarity. The key to success is to anticipate the change and set up early – even if that means standing in the rain with your camera under a raincover. If you set up after the rain stops, you will miss the moment.

Focusing

Obtaining front-to-back sharpness doesn’t need a maths degree, just a little patience.

Differential focusing

Although we are used to the majority of landscape images exhibiting front-to-back sharpness in ‘near-far’ compositions, there is no rule to say all our landscapes have to follow this convention. In fact, by doing the opposite, you can make your images stand out from the crowd. Use a telephoto lens and open it up to maximum aperture to restrict depth of field, and then either throw the background or foreground out of focus to force attention onto your main subject. An out-of-focus foreground can make an effective frame for the subject and add a touch of impressionism.

Double distance focusing

The usual advice for maximising depth of field is to focus ‘a third of the way in’. However, this is rather vague and doesn’t guarantee good results when there is close foreground. Focusing on the hyperfocal distance is more precise, but if messing around with charts isn’t your thing, try double distance focusing. Identify the nearest object in your composition that you want sharp, calculate its distance from the camera and then focus at double that distance. If you are shooting with a wideangle lens and a mid-to-small aperture, this technique will deliver front-to-back sharpness. To be sure, check the review image for depth of field.

Focus stacking

With very close foreground interest, even careful focusing may not get you enough depth of field. One option is to use tilt–shift lenses, but these are expensive optics. A cheaper alternative is to use a technique known as focus stacking. Take a series of shots, covering the scene from foreground to infinity, with depth of field overlapping from one shot to the next. These can then be blended in software into a single file with extensive depth of field. There are plenty of online tutorials to help you perfect the technique.

Back-button focus

Purists will try to insist that you focus manually, but autofocus is quick, convenient and accurate, so why ignore it? More important is to know where in the scene to focus and to make sure that focus is locked once achieved. Back-button focus enables this. Via a custom setting, most cameras allow you to assign one of the buttons as an ‘AF-On’ button and decouple focus from the shutter button. You then focus with the back (AF-On) button and when you press the shutter button, the camera does not refocus before opening the shutter.

Kit list

Sun app: I use a sun position app, such as Sun Surveyor or Sun Seeker, in order to help me find when the best light is at a particular location.

LEE filters: In my landscape photography arsenal is a set of LEE filters (above) including various grads, neutral-density filters and a polariser.

Raincover: I use chamois leather as a raincover to protect the camera from the elements and also for wiping kit down if it does get wet.