The global pandemic has changed the very nature of street photography over the past 18 months. Steve Pill speaks to three very different pros about new briefs, adapting techniques, and what the future holds.

Taking street photos during the pandemic: Paola Franqui

Paola’s aim is to record fleeting moments that capture the environment and atmosphere. Sony A7R III, 55mm, 1/160sec at f/1.8, ISO 100

Paola’s tips for pandemic street photography:

- I constantly switch lenses. When I get too comfortable, I need to do something different.

- Be respectful. If I take a photo of someone and they look at me, I immediately smile to show I’m not doing any harm.

- Study other photographers’ work. It’s a way of finding inspiration to make something for yourself.

Paola Franqui’s photographs are a product of her environment in the best possible sense. Whether shooting a Parisian boulevard or a Tokyo subway, she manages to capture the spirit of each place via a series of telling moments that play out like stills from a long-lost 1970s film.

Her most frequent subject is Manhattan, which she infuses with a timeless romance and the outsider perspective of a Puerto Rico-born photographer living an hour away in New Jersey. ‘I don’t think there’s any place like New York City. The characters, how it feels, the smell, the chaos,’ she says.

‘Photographing the city at the beginning of this year was very challenging because it was so quiet – that liveliness, that spark was gone.’ Paola delights in human interactions, so the lack of visible smiles among masked crowds proved particularly difficult. ‘You had to try harder to find something else, that extra thing that’s going to make the photo work,’ she says.

Capturing human interaction is central to Paola’s work Sony A6000, 19mm, 1/800sec at f/2.8, ISO 100.

When a full lockdown prevented regular jaunts to New York and beyond, she began to look through her archive, enjoying the world vicariously through her images and picking out forgotten frames to edit. ‘I’m very big into colour grading and I would spend hours and hours a day just trying to bring things back to life with different colours and different editing styles. That was something that kept me sane.’

This period of self-reflection also resulted in Paola’s first photobook, Momentos, published this summer by London’s Setanta Books. ‘What I said to them at the beginning was that I wanted this book to be like a movie: from the first page to the last, I wanted to tell a story; I wanted all of the images to speak with each other. And I think the way they did it was very successful.’

The cover image, ‘Until We Meet Again’, is typical of Paola’s approach: sepia-tinged colours, an exacting composition, and the photographer’s own image inserted into a complex interaction of reflections. That final element was inspired by Vivian Maier, the reclusive nanny whose vast street photography archive only emerged after her death in 2009.

Paola spent hours during lockdown picking out images from her archive to edit with different colours and editing styles. Sony A7R III, 24-70mm, 1/160sec at f/4, ISO 100

Paola discovered Maier’s work at a point when she had grown disillusioned with her own output: ‘I was immediately obsessed. I was like, “How was this person real?” I bought all of her books and I would spend hours looking at her work.’

Maier also indirectly inspired No Film Wasted, a second Instagram account through which Paola and her wife, Laura, post scans of mid-century film slides. ‘Every time we go thrifting, we try to find more,’ she says excitedly. ‘Our collection is crazy; I don’t know what I’m going to do with them. I have maybe like 10,000 slides and I’m not going to stop.’

That passion for photography has been evident ever since Paola first started shooting street on an iPhone 5 nine years ago and Instagram has proved a valuable role in her development – not only in terms of building an audience of more than 325,000 followers, but also because most of her commercial clients first found her via the social media platform.

As an ambassador for both Sony and Adobe Lightroom, Paola also feels an added responsibility to capitalise upon her increased profile in the industry. ‘I’m working for females, for Latinas, for queers,’ she says proudly. ‘I want to pave the way for more female photographers because I know how hard it is for us. We have to work extra hard.’ While Paola is clearly putting in the hours, she has certainly found a way of making her photographs seem effortless.

About Paola:

Paola, also known as Monaris, is a Puerto Rico-born photographer based in New Jersey, USA. She is an Adobe Lightroom Partner and Sony Ambassador. Her first photobook, Momentos, was published this summer by Setanta Books.

To see more of her work, check out her website and Instagram.

Taking street photos during the pandemic: Neil Hall

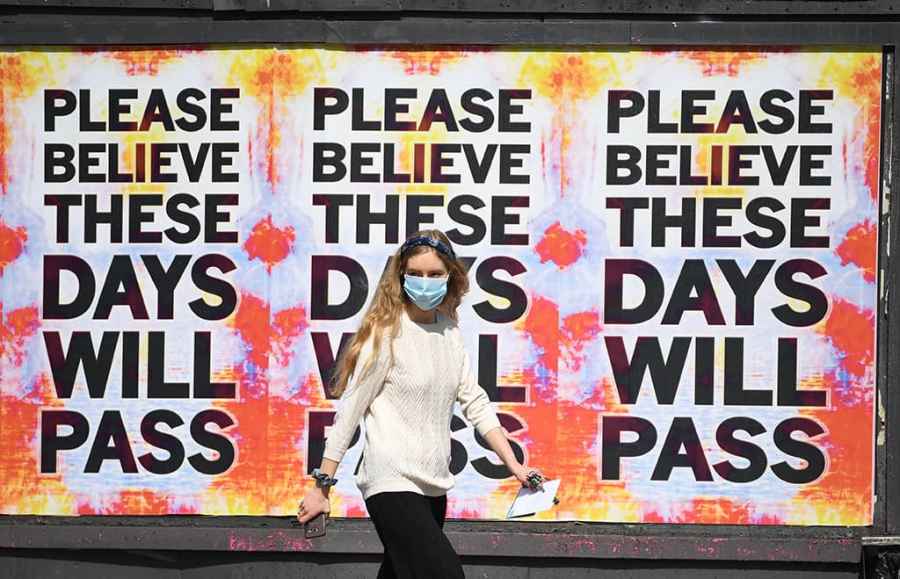

Neil Hall was keen to include people to humanise scenes, to tell the story unfolding in front of him Nikon D5, 1/3200sec at f/3.2, ISO 125

Neil’s tips for pandemic street photography:

- Stick to autofocus for street photography. You are just as likely to screw up as you are on manual focus, but it’s faster.

- My go-to lens for wide shots is a 24-70mm. Anything wider is so beyond the normal field of vision that it becomes almost like an effect.

- If you are trying to tell a story in a single frame, you must pick a point of interest. As a rule, I shoot quite wide open – usually f/2.8.

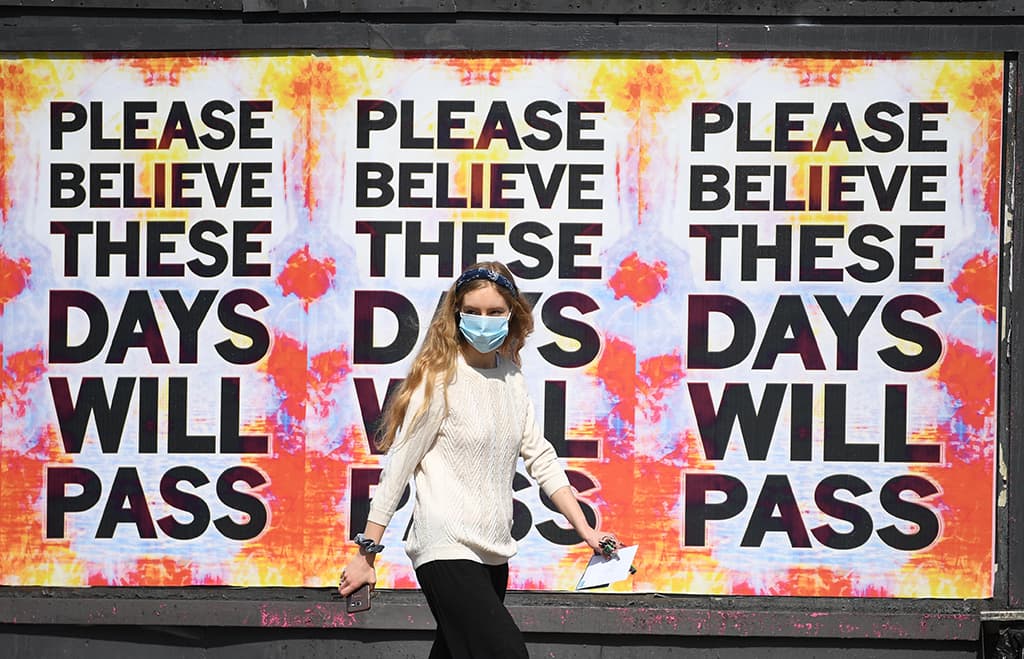

When daily life ground to a halt for many of us 18 months ago, it largely remained unchanged for Neil Hall. As a staff photographer for European Pressphoto Agency (EPA), he continued to commute across London every day while his classification as a ‘key worker’ meant his daughter stayed in school. Nevertheless, while Neil’s routine appeared much the same, his output did not.

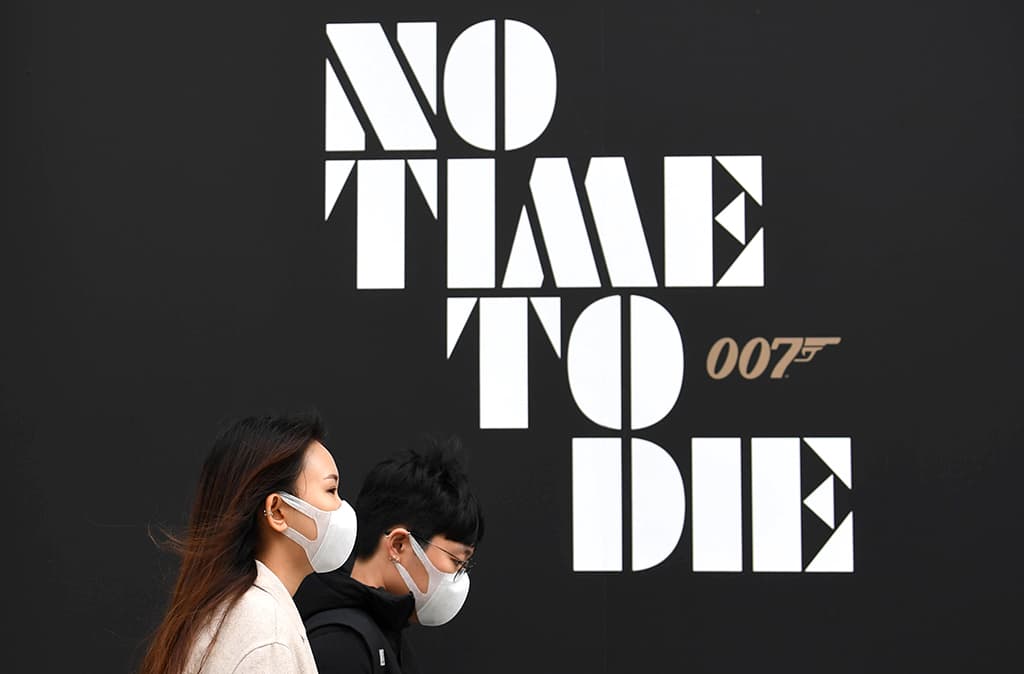

‘The job of a news photographer is often to show or reflect the world – therefore obviously as the world completely changed, the nature of the pictures you take and how you take them has completely changed,’ he explains. ‘In effect, we became pure street photographers.’

With public life on hold, the 41-year-old was given a much broader brief to seek out visual clues and signifiers that would illustrate how daily life was changing in unprecedented ways. ‘The trick is to remember that what is happening today might not be happening in a week, so you’ve got to have that historical eye on the situation,’ he explains.

Neil quickly went from documenting masked shoppers running home with armfuls of toilet roll to shooting deserted London streets at what should have been rush hour.

Neil was tasked with capturing moments representative of how daily life was changing during the pandemic. Nikon D5, 70-200mm, 1/800sec at f/4, ISO 400

While the silence of an empty Piccadilly Circus was striking at first, he says, the resulting photographs were ultimately unsatisfying: ‘Unless it’s a very clever piece of visual design, street photography needs people in it to humanise it and tell the story – because stories are about people.’

Once people began to return to the city, they brought with them a fresh set of challenges. Government restrictions on daily exercise meant that photographers were eyed with greater suspicion, further exacerbating an already fraught dynamic between public and press.

‘Certainly, in the last five years, with the explosion of social media, people have become more aware of what can happen to a picture,’ says Neil. ‘And with that comes a significant mistrust of photographers, more so than at any point in history. If you look at some of the great photos that Henri Cartier-Bresson captured, you probably couldn’t take those now in quite the same way.’

Verbal attacks have become a regular occurrence. ‘I always find that people like social documentary photography except when they’re in it,’ he notes drily. To help in this respect, Neil set aside his trusty Nikon D6 for the silent shutter of the mirrorless Nikon Z 7. However, he is adamant that there is much more to photography than good kit.

Shooting deserted London streets at rush hour soon became the new norm Nikon Z7, 24-70mm, 1/250sec at f/5, ISO 64

‘A picture isn’t just about the technical aspect,’ he says. ‘Anyone can learn to paint to a reasonable standard, it doesn’t make them Picasso. You can swallow a thesaurus, but it doesn’t mean you’re going to be Hemingway.’

Neil’s appreciation for the more elusive qualities of street photography took shape in 2003 when, as a young archaeology graduate, he visited two landmark London exhibitions: Walker Evans at the Photographers’ Gallery and Tate Modern’s Cruel and Tender. ‘That was a mind-blowing experience for someone who didn’t have a great background knowledge of photography,’ he says.

Neil promptly took a job at his hometown newspaper, Tamworth Herald, working his way up via freelance shifts with the nationals and six years as a stringer at Reuters, before joining EPA in 2017. As his working day now settles back into a more regular routine of sporting events and political summits, it is still the simple challenges of classic street photography that continue to motivate his practice.

‘It’s like trying to capture a rare butterfly while you’ve got a large bell around your neck,’ he says. ‘It’s really difficult but when you get it, it’s more satisfying than anything else.’

About Neil:

West Midlands-born Neil is a staff photographer and video journalist for the London bureau of the European Pressphoto Agency (EPA). In 2020, he was named Arts & Entertainment Photographer of the Year at the BPPA Press Photographer of the Year awards.

See more of Neil’s work at EPA and his website.

Taking street photos during the pandemic: Craig Whitehead

Craig likes to push saturation in post to emulate the orange tones of Kodachrome filmCraig’s tips for pandemic street photography:

- Don’t fret about having the newest kit. It doesn’t matter what a camera can do, as long as you know how to get it to do what you want.

- Move around, stalk your subject a bit. Eye-level, stood where you are is almost never going to be the best version of that shot.

- Get up close to a subject, just once. Even if you never get that close again, knowing that you can when the moment arises is really important.

It’s strange to think, now that he has amassed more than 250,000 Instagram followers, but Craig Whitehead only turned to street photography by chance.

The Cambridge School of Art graduate picked up a camera purely as a creative outlet during his lunch breaks from work, while even his specialist subject came about by necessity. ‘The only option was to shoot the city because that’s where I happened to be,’ Craig explains.

‘If I had been based in the countryside, I’d probably be a landscape photographer.’ Craig’s only real experience of street photography at that stage was the unflattering flashgun portraiture of Magnum photographer Bruce Gilden.

He tried imitating a similar style, shooting wide and close, yet quickly realised this was not for him. ‘I’m not going to stick my camera in someone’s face while they’re biting into a burger, it doesn’t interest me,’ he says. ‘I’m definitely more in the camp of trying to make art.’

Shooting through objects to give the appearance of layers can often be seen in Craig’s street scenes

During his degree, Craig used multiple sheets of tracing paper to carefully build his illustrations and he takes a similarly layered approach to street photography. Rather than focusing purely on people, he is more interested in the scene as a whole, so he will select interesting backdrops or objects to shoot through first, before identifying repeat patterns of behaviour that allow him to pre-empt how figures might enter into the frame.

He views the process as a numbers game – and he fancied his odds better with a camera. ‘You could work for a week on a couple of illustrations and hate everything you’ve done; whereas I can take 1,000 photos in a day and it doesn’t matter if I don’t use 999 of them,’ he explains.

Craig will often find an interesting backdrop first and wait, pre-empting where people might pass through the scene

That matter-of-fact attitude extends to editing and an approach that might alarm photojournalistic purists: Craig thinks nothing of removing unwanted details that have strayed into shot, like wires or bag straps. There’s a similar amount of artistic licence used in colour grading, as he pushes the saturation and often skews reds towards the slight orange-bias of Kodachrome film.

The avoidance of what he calls ‘known colours’ is the key to preventing pictures from looking false or overly worked. ‘It’s the skin tones that give it away,’ he explains. ‘If people like blue highlights, you can tell as soon as you see a face in there. But you can play around with colour a lot if you protect those indicators.’

Craig agrees that his appetite for street photography is bordering on an addiction and it is clear that he has been suffering withdrawal symptoms. ‘In the past 18 months, I just haven’t been producing,’ he admits.

‘It sucks. That feeling of just surprising yourself and getting a shot that you never expected is the entire reason to keep going out and doing it, so not having any of that for the best part of two years is awful. I’ve had to accept that everyone is in this same situation, it’s not just me.’

The extended lay-off has given Craig time to reassess his practice. He cites Saul Leiter and Ernst Haas as the ‘Old Masters’, and he is keen to emulate their broader interpretation of the subject. ‘Why am I pigeon-holing myself completely to street?’ he asks rhetorically.

‘They didn’t think like that, they just shot what they wanted – especially Haas. People hold him up as one of the street photography masters, but half of his work doesn’t even have anyone in the frame. It’s just beautiful art.’

Suitably inspired, Craig intends to adopt a more generally creative approach, trying his hand at different subjects and alternative techniques, like multiple exposures. ‘It’s a good time to refresh and experiment,’ he says, that addiction showing no sign of abating.

About Craig:

Under his Sixstreetunder handle, Cambridge-based Craig has become one of Britain’s leading street photographers. He teaches workshops with Skillshare, and he is working on a follow-up to his first sold-out photobook, New York. Explore more of Craig’s work at www.instagram.com/sixstreetunder and purchase prints via www.sixstreetunder.com.

New to street photography? Check out our Beginners guide to Street Photography here.

Further reading

Best Camera For Street Photography

Street photography in lockdown

What makes great street photography?

Black and white street photography: Tips and techniques from the experts