Infrared photography still divides opinion. For some, it’s a great way to add mood and atmosphere to images, particularly black & white, while for others it’s a distracting gimmick. I can see both sides of the argument, but some of my favourite photography has used infrared, such as Simon Marsden’s haunting shots of Venice, or Richard Mosse’s superb Aerochrome IR film project in the Congo.

So, hearing that there had been an upsurge of interest in infrared during the lockdown, I decided to convert an eight-year-old Olympus OM-D E-M5 mirrorless camera. Would I greatly extend the life of this old warhorse or hobble a perfectly good back-up?

Before going on, let’s just recap the basic principles of converting a mirroless camera to infrared. Put simply, there are two options. One, add a glass IR filter inside the camera. There are a range of options, but 830nm, 720nm, 665nm, or 590nm glass filters tend to be the most popular (nm stands for nanometers, the measurement unit for infrared wavelengths). The longer wavelength conversions, such as 720nm and 830nm, are mainly used for black & white, as above 720nm there is very little colour information available.

Shorter wavelength IR conversions, such as 590nm, are popular for those ‘false colour’ effects you either love or hate (orange skies, bright red or bleached white foliage and so on). Or, for a similar price, you can go for a ‘full spectrum’ conversion (i.e. removing the internal hot mirror), which is generally more flexible as it doesn’t involve fitting an IR filter inside your camera – just optical-quality clear glass to protect the exposed sensor. With full spectrum, the camera essentially gains extra light sensitivity, so it is able to capture infrared images, ultraviolet light images and more.

Don’t try this at home

You then add IR filters to your lenses for specific effects, such as black & white at 720nm, or 590nm for false colours. Here’s the thing: you can also change back to using the camera in the ‘normal’ way simply by adding a UV/IR hot-mirror blocking filter. So, on the basis of recommendations from other AP contributors, I decided to get my Olympus guinea pig converted to full spectrum by Protech Photographic, who’ve been in business for over 30 years. Camera technician Kelvin Stonebrook explains the process. First, he is keen to stress that conversion is not really something you should try to do at home.

‘You can get an a shock if the camera has a built-in flash,’ he explains. ‘Some cameras are pretty easy to convert, such as the Nikon D70, but taking apart a mirrorless camera is usually complicated. Whilst DSLRs can indeed be converted, mirrorless are more flexible. With a DSLR if you opt for a full spectrum conversion you won’t be able to see through the viewfinder when using an external higher nm filter so you’ll have to set the exposure and composition first – you can use live view if your DSLR has it which makes things a little easier.’

‘If it is a dedicated IR conversion it makes no difference to the viewfinder – you can use as a standard camera as the glass IR filter is behind the camera mirror. Because a mirrorless camera focuses off the sensor you are focusing infrared light as opposed to visible light on a DSLR; additionally mirrorless cameras do not have to be adjusted for a particular lens as DSLRs would need to be.’

‘We convert many DSLRs, including for astro or scientific work, but lots of people are choosing to have mirrorless cameras converted as they may have a spare from an upgrade and the cameras tend to be a lot lighter if used as a second body.’

As mentioned, false colour infrared is not to everyone’s taste, so if you just want to shoot black & white, Kelvin recommends a 720 or 830nm conversion. ‘You don’t have to faff about with lens filters, so you can see why not everyone goes for full spectrum.’ If you want to experiment with false colour, Kelvin recommends a 590m conversion, which produces golden yellow leaves or bright blue skies, or 665nm as a good overall compromise.

Filter facts

We mentioned the outstanding infrared work of Richard Mosse at the beginning, who uses the hard-to-find Kodak Aerochrome film. To get the Aerochrome look digitally has never been easy unless you are a Photoshop expert, but you can try using a dual band filter, or the IR Chrome filter from Kolari Vision in the US (it’s not cheap, however, at around £100 plus shipping). Filter tips Not everyone will want to spend that much if they only take IR images irregularly, so what about cheaper filters, which you can easily use with a full-spectrum converted camera?

‘They work, but whether a purist could tell the difference between something cheap off Amazon or a pricier filter, I don’t know. Not everyone has the money for Schott glass B+W filters. You will get better quality glass if you pay more, and you have to be careful you don’t end up with an acrylic filter. Definitely avoid variable IR filters that claim to go up from 590nm, as you can get streaking and lines on the image.’ Another issue to watch out for is hot-spotting – a bright spot in the centre of the image that appears at narrower apertures. Some lenses are more susceptible than others, so check out the extensive database at kolarivision.com/articles/lens-hotspot-list.

Editing advice

Getting your camera converted, whether via a full spectrum conversion or adding a specific internal filter, is one thing, but to get the most from infrared digital photography, you also need to be aware of potential issues when shooting and editing. I noticed that it was quite easy to blow out the highlights, particularly in foliage.

‘If there is a lot of IR light coming off the foliage and you expose for, say, a church, you may indeed notice the foliage blows out,’ says Kelvin. ‘You can compensate for this, but it’s also a good idea to choose matrix metering rather than spot. Also, as you come down the spectrum, you will be getting more visible light – so a 720nm filter is more user-friendly than a 900nm, which requires a lot of light. Furthermore, with black & white, a 720nm filter will usually give you more “bite” than you’d get with a 590nm which lets in more visible light so foliage appears softer.’

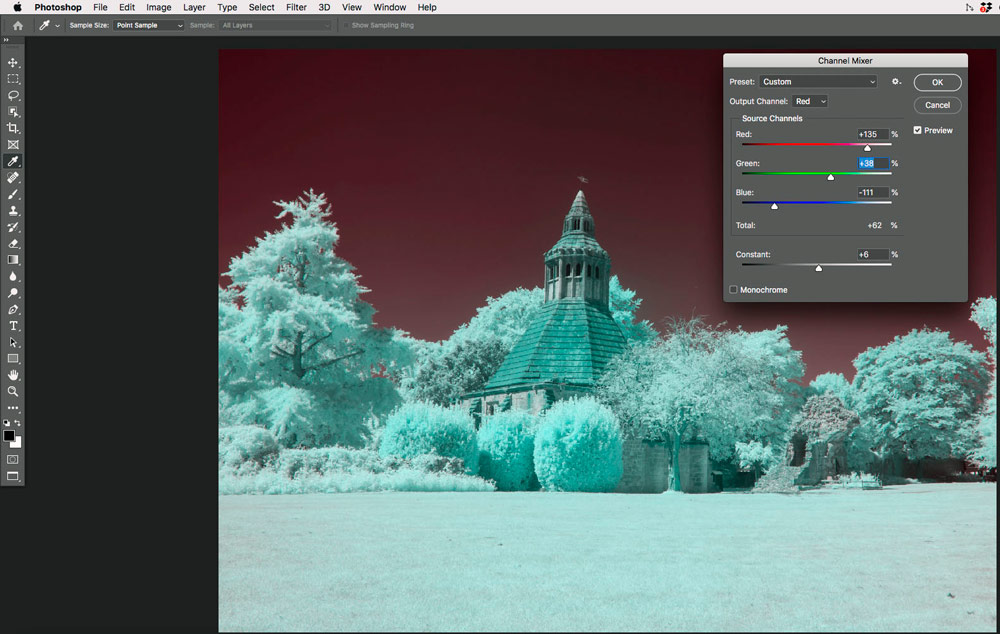

For editing, Kelvin always recommends setting a custom white balance when you add a lens filter (or have your camera converted with a specific IR filter). ‘Shoot in JPEG and raw at the beginning, as if you put a JPEG in Photoshop you will see what you see on the back of the camera and can then play around with the Channel Mixer in Photoshop for various effects. Put a raw file into Photoshop and it will render the image pink, as it ignores the custom white balance – so you’ll need to reset it.’ So to sum up. This article probably won’t convince committed IR-phobes, but I learned a lot getting my old Olympus camera converted, and it’s certainly added another weapon to my creative arsenal – particularly when it comes to black & white.

Which cameras make the best conversions?

Many people convert older cameras as it’s less of a risk. Which cameras are the most suitable? ‘They all have their pros and cons,’ says Protech Photographic’s Kelvin Stonebrook (see his workspace above). ‘Panasonic makes it easier to adjust white balance without digging through menus, and Fujifilm and Olympus work well. Obviously a full-frame sensor will give you higher-resolution files – the latest full-frame models from Sony and Nikon are particularly good. But as we see here, you can get great results with a camera that is nearly ten years old, so a lot of it comes down to your allegiance and range of lenses.’

A full spectrum of possibilities

Rather than thinking of a full spectrum as an IR conversion per se, it’s more accurate to think of it as a conversion that greatly increases the light sensitivity of your camera – so it can naturally detect more infrared light as part of this process. ‘If you set a custom white balance using a white or grey card and shoot a normal scene, it will look pretty normal except for the trees and foliage – they give off a lot of infrared light,’ says Kelvin. ‘The foliage will often show up as slightly soft, too, so adding a filter gives you punch.’ Another big advantage of a full spectrum conversion is better low-light results. ‘If you are photographing animals at night, for example, you get extra light sensitivity at the top end. Recently, we did a full spectrum conversion on a Canon EOS 7D for Russell Savory, who is covering the reintroduction of beavers to Essex after hundreds of years.’

Further reading

Follow AP on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube and TikTok.