Churches are an easy go-to topic for architecture or landscape photographers. There’s plenty of them, they’re usually pretty welcoming to cameras and you don’t have to rely on the weather to photograph them. But, perhaps one downside is that many traditional churches look quite similar to each other. Looking at Thibaud Poirier‘s fantastic series Sacred Spaces however, demonstrates that there are myriad opportunities to find unusual ecclesiastical architecture if you’re prepared to put the legwork in.

Most of the churches in the series are found in Europe, with many in France (where Thibaud lives) but some in neighbouring countries such as Germany. However, he also ventured further afield particularly to the US and Japan. The Sacred Spaces series is just one of several Thibaud has worked on in recent years, including one particularly popular one on libraries.

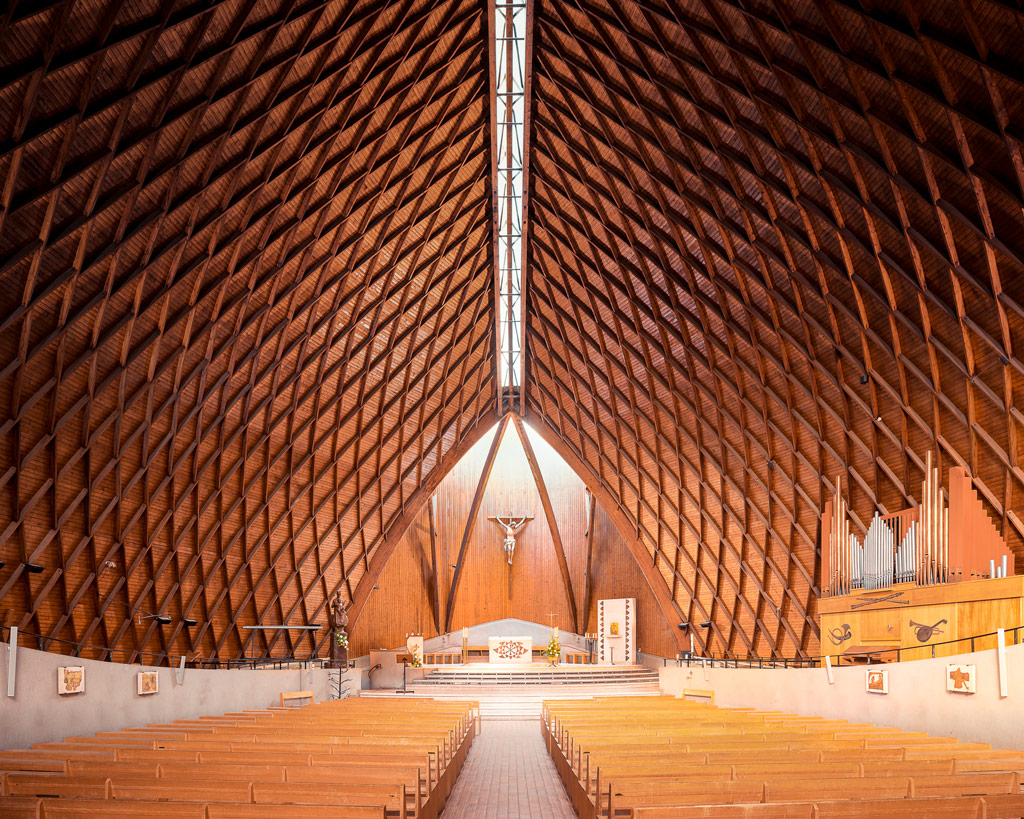

St. Ignatius Church, Tokyo, Japan (Sakakura Associates 1999) Photo credit: Thibaud Poirier

A loose criteria was applied for finding the churches. As he explains, ‘I didn’t necessarily want a set number, but usually when I do a series I try to have at least 15 or 20 sites, just to have that sense of representation of what I’m trying to achieve and photograph. I wanted to photograph churches from the 20th or 21st century; usually churches that were either modern for the time or used new materials like concrete and specific types of glass, with new architectural techniques. Most of the churches I photographed were from the 1940s, ’50s or ’60s – this is a time period I particularly appreciate for the use of new modern techniques – and mostly concrete as a material.’

You might think from the abundance of images in the series (more can be seen on Thibaud’s website) that these sites are not too difficult to find, but in many cases it was a real mission. ‘Finding information about these churches was very hard. Unlike popular, very-old churches in city centres, these are ones that people don’t visit to take photographs of inside. So I might be basing whether to go on a long trip off a picture from the ’50s with no real idea whether it was still in that state. Or I might have a blurry iPhone picture to look at.’

Eglise Notre-Dame de Royan, Royan,France. Photo credit: Thibaud Poirier.

Once he started publishing pictures it became easier to learn of other potential sites. ‘One of the nice things is that a lot of people send me emails and say things like “oh I have one like that in my little town which is not really famous” and that kind of thing. People will send me shots so I can see, or I might get sent local magazines with specific photos – people are generally pretty happy to share locations.’

Something to take into account was the fact that, unlike tourist-friendly churches, many of these places are not open all week. This turned out to be a plus at times though. ‘With other spaces I’ve photographed – say the libraries – they’re not empty very often. Sometimes it might take six months or a year to get the access I need as it’s such a complicated administrative process. With these churches, it was mostly a little easier because most of the time they’re pretty much empty.’

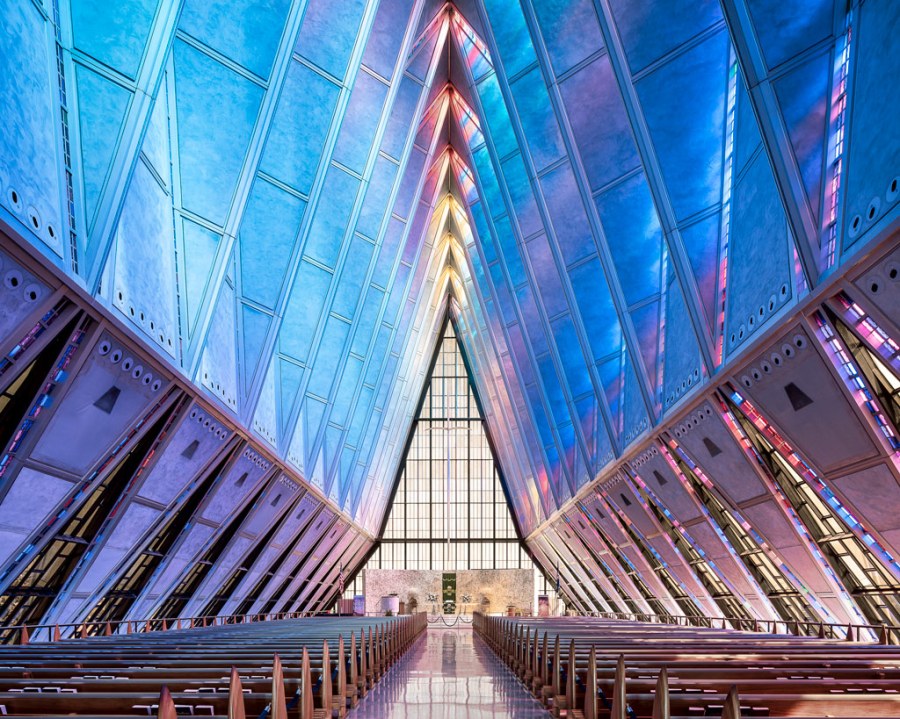

Saint Moritz, Augsburg, Germany (Jon Pawson 2013) Photo credit Thibaud Poirier

Part of the beauty of this series is its simplicity. The set-up is always the same and relatively straightforward. He uses a Sony A7R series camera (later images are shot with a Mark IV, but he previously had an older version) and uses Canon tilt-shift lenses to ensure the photos are as accurate as possible at the point of capture without relying too much on editing. ‘I think 90% or 95% of them are taken with a 24mm tilt-shift. A few are with a 17mm, but that usually gives a bit more distortion and is a bit too wide for some shots.’ He always uses a tripod and often uses multiple exposures to get the look he’s after – but describes it overall as a very simple process.

Despite so much effort and time being put into research, travel and actually being at the church, he’s usually only looking to shoot just one picture. ‘I want the same point of view so it’s consistent through the series. Depending on the size of the church or its architectural details I might take a few more, but it’s usually the main central shot that I try to take.’

Meguro Church, Tokyo, Japan. Photo credit Thibaud Poirier

As for lighting, that’s pretty simple too – it’s always either natural or available light. Luckily, churches are often purposefully built around creating beautiful light. ‘I have selected these spaces because of their architectural qualities, and most of the architects designed and built the churches with light in mind. Where natural light isn’t so good, I play with the lighting in the church – maybe I’ll turn on one light here, one light there, then take the shot – then turn on other ones and take another shot. That way I can light the church without having to see bright light bulbs in the finished piece. In these cases having someone around who can help with the light in the church is a bonus.’

Another way to keep the series looking uniform is to choose specific weather conditions where possible. ‘Usually I try to go when it’s overcast but pretty bright. That gives kind of the same feel from one photo to another. Sometimes having really bright sunlight come into the church it can overpower and create too strong a contrast.’

Grundtvigs Kirke, Copenhagen, Denmark. (Peder Vilhelm Jensen-Klint, 1927) Photo credit Thibaud Poirier

Generally, Thibaud will shoot at similarly narrow apertures to get the greatest depth of field possible, with shutter speeds dependent on the available light. ‘Sometimes it can be pretty long exposures; there’s one church in Copenhagen where everything looks pretty bright – that’s 30 seconds. I rarely go below one second.’

Thibaud has his own theories about why the series has resonated so well with pretty much everyone who’s seen it. ‘What drew me to do the series is that whether you’re religious or not, we’ve all been in churches. Some of the nicest and most popular monuments in France are churches. We all have this idea of what a church is, but when I discovered there were totally different architectures, and sacred spaces was a way for great architects of the 20th century to develop their creativity and share their different techniques, that struck with me. I think when people see the series it’s peculiar for them – some of them are like something out of sci-fi. It’s interesting that there were some different ideas in the 20th and 21st centuries to convey what the church wanted to, through modern and innovative architecture.’

Eglise Notre-Dame du Chêne, Viroflay, France. Photo credit Thibaud Poirier

As for the churches themselves – Thibaud says many of the staff probably haven’t seen the work. ‘I haven’t had too many interactions, but when I have it’s mostly been very positive because I really try to make the best out of the space and to show it as I see it – which is maybe in a more beautiful light than it is in reality. That said, some churches don’t have a website or anything, so it’s not always clear who to contact. I’m certain some of the people who work there don’t know me and haven’t heard of me. But generally the return on the work is very positive.’

When it comes to words of wisdom for anybody aspiring to shoot similar to him, Thibaud’s suggestions are very simple. ‘For me it was all about photographing what I found beautiful. When you look at my series, the technique is very precise but it’s not particularly innovative. It’s just that it’s similar and disciplined. The most fun part is the hunt for the spaces, it’s doing all the research and going on Google or Instagram and trying to find these gems and travelling. When I go to these churches, though I usually only take one picture, I probably spend an hour in there to take it all in and walk around and see the little particularities of each church. I think it’s really about photographing what you love, being present while you’re there and enjoying the space.’

Saint Moritz, Augsburg, Germany (Jon Pawson 2013) Photo credit Thibaud Poirier

Thibaud is no longer working on Sacred Spaces but admits there are plenty of churches he’d still like to shoot. Should he get the opportunity, he might return to it. For those in the UK curious to find modern churches to have a go at something similar, there’s three that Thibaud would love to photograph: Clifton Cathedral in Bristol, Cathedral of St Michael in Coventry and Bishop Edward King Chapel in Oxford. Do send us your pictures if you’ve been, or visit at any point.

Thibaud Poirier is based in Paris. He spent his childhood in many cities, including Buenos Aires, Montreal, and Tokyo. It was in the latter that he developed a fascination for architecture and urban environments. Equipped with an acute understanding of architectural principles and a keen sense of composition, he merges his technical expertise with his artistic vision. narratives embedded within the spaces he portrays. His work has been exhibited in galleries across the world and he often collaborates with renowned architects and design firms. See more of his work here: thibaudpoirier.com

Read more:

Abstract architecture photography tips to transform your building shots

Master black and white building photography

Best lens for landscape photography in 2023

Follow AP on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube and TikTok.