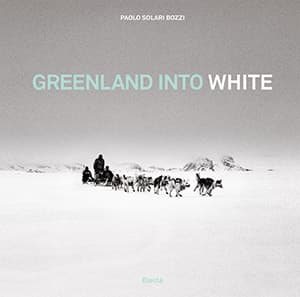

This shot from Greenland into White shows Tiniteqilaaq is a settlement in southeastern Greenland. Credit: Paolo Solari Bozzi

Greenland seems a rather odd name for a glacier-covered island lying mostly within the Arctic Circle. But being a little free and easy with the truth allowed Erik the Red to persuade fellow Icelanders to settle here in the 10th century (so legend has it). In his defence the island was much warmer than it is today and there are accounts of lush green meadows and fjords positively fizzing with fish.

Having established their colonies here, the gutsy Icelanders thrived in Greenland for the next three centuries, but in the middle of the 14th century the climate began to change leading to an era known as the Little Ice Age. The settlers were farmers, so the arrival of this inclement weather hit their crops and livestock hard. As a consequence they turned to the sea for both food and trade, but their trips became more treacherous as the sea grew ever stormier. By the beginning of the 15th century most of the original settlers had abandoned this white desert, leaving the Inuit population to adapt to this new environment.

In 2016, when Paolo Solari Bozzi travelled to Greenland to photograph the Inuit communities and the landscape they inhabit he expected to see some individuals wearing bear and seal furs, but he was wrong.

Continues below…

[collection name=”small”]

“I wasn’t surprised they were wearing Western clothes,” he recalls, “but I was surprised by how many of them were dressed this way. The Inuit are going through a period of transition, which is causing them to abandon some of their centuries-old traditions.” One such tradition involves living underground during the winter – something grandparents of the current generation would have done.

It might seem strange to those of us living in relatively mild climates, but polar bears construct temporary dens to shelter from severe weather, and there is much to be learnt from nature. “Wooden houses were imported from Denmark about 100 years ago,” says Paolo. “Before then the Inuit made caves in the ground and used wooden planks to cover the hole.” The wind here can reach speeds of 200km an hour, which is often no match for these wooden cabins.

The Inuit live in wooden cabins like this one in Sermiligaaq. Credit: Paolo Solari Bozzi. Greenland into White

The winter of 2016 (when Paolo visited the island) was relatively mild, but he is quick to point out that this isn’t something to celebrate. “Everything is getting milder due to global warming,” he says. “As photographers we have a duty to use our images to make the world aware of what’s going on – despite Mr Trump’s allegations and denials about climate change. All he needs to do is to take an aeroplane to Greenland and talk to the people there and they will tell him that every year the ice is melting earlier.”

An offshoot of this warmer weather is the effect it has on the hunting season. The Inuit still shoot polar bears and hunt seals, but the number they kill is strictly controlled by law. Joining them on a hunt is forbidden, and Paolo would have incurred a large fine if he had taken part in any of the expeditions. “If you offered them a million pounds they still wouldn’t take you because then it becomes a business,” he suggests. “It’s a good law. The Inuit are not allowed to hunt on snow bikes so they use sledges to give the polar bear a fighting chance.” While he never witnessed a kill, Paolo was present when a dead bear was brought back to town. It took over an hour for the animal to be cut up and divided into bags – some meat was kept for the dogs, some set aside for human consumption, and the fur was left out to dry. “The Inuit don’t shoot for fun, it’s not a sport,” says Paolo. “They eat what they kill, and fishing and hunting is in their genes.” The huntsmen can be gone for weeks at a time, with no way of contacting their families back home.

A polar bear skin is left out to dry at Kap Hope. Credit: Paolo Solari Bozzi. Greenland into White

There is no margin for error in the Arctic, and the weather is beyond brutal. Paolo had a taste of the hostile conditions while he was travelling by dog sled. “The temperature was about -25°C, but with the wind chill factor it was -40°C for sure,” he recalls. “You have to be careful because you are totally immobilised. You need to wear goggles, because when the dogs go they really go – they can reach speeds of up to 30km an hour. The snow comes at you horizontally and you can get icicles in your eyes if they are not protected properly. It’s serious stuff.”

It comes as no surprise to learn that Paolo invested a lot of time, and money, researching and buying equipment before he left his home in the Swiss Alps. What’s more surprising though is the fact that he decided to shoot the project on black & white film. “Analogue is fun,” he laughs. “I would much rather work in the darkroom than sit in front of a computer.” In 2011 Paolo abandoned his screen-based job as an investment banker after receiving a cancer diagnosis and undergoing a successful course of chemotherapy. Shortly afterwards he spent five months travelling across Southern Africa in his faithful Land Rover. “I like infinite spaces,” he reveals, “that’s why I went to Africa, and that’s why I chose to spend two months in Greenland.”

The Inuit hunt seals and polar bears, but numbers are strictly controlled by law. Credit: Paolo Solari Bozzi. Greenland into White

Handling film in sub-zero temperatures is not without its challenges. Paolo kept his equipment as warm as possible by tucking it in between his fleece and his Arctic jacket, but changing the rolls was tricky. “One of my cameras [a Fujifilm GX617] shoots beautiful 6 x 17cm panoramas, but I only get four frames on a roll,” he explains. “Sometimes I took off both pairs of gloves and it was so cold that I couldn’t move my fingers to change the film – it’s something I grew accustomed to in the end!” Despite temporarily losing the feeling in his fingers Paolo was very happy with his decision to use film rather than digital for the project. “The more electrical components a camera has, the more there is to go wrong,” he suggests. “If I had used a digital camera the batteries would have drained too quickly in the cold, and if something had gone wrong I was in the middle of nowhere so I might as well have packed up and gone home.”

Like many photographers, Paolo finds colour a distraction, and he delights in the physical process of producing a traditional print. “When you develop and print a film you use your whole body,” he says. “When you’re in the darkroom you hold a tray of developer and move it up and down, you cut the paper, you hold the print in your hand and sometimes the beauty lies in the imperfection. Years ago somebody asked me where I meditate and I said ‘in the darkroom.’ I have my music in there, it’s dark, I like the smell of the chemicals, and I become immersed in the process.”

Creating black & white prints has proven integral to the project. While Paolo was in Greenland he met Ragnar Axelsson who he describes as ‘the father of Arctic photography’ and Carsten Egevang, a photographer and dedicated researcher of Arctic seabirds. The three men decided to arrange an exhibition of their work in the hope that it would raise awareness about climate change. The show, entitled ‘The Arctic. Final Frontier’, featured 120 prints and first appeared at the Casa dei Tre Oci (a palace by the water) in Venice. Having completed a successful three-month run it will be moving on to the Triennale in Milan (8 Feb-25 Mar 2018).

When the dogs are really going they can reach speeds of up to 30km an hour. Credit: Paolo Solari Bozzi. Greenland into White

“The idea is to create awareness through beautiful, strong images, not the boring classical reportage photographs of the ice cracking,” says Paolo. “There is an aesthetic component that will gratify the visitor, but the aim of the show is to highlight the problem of climate change.” To reinforce the point the team arranged a one-day summit during the exhibition and invited politicians, professors and leading experts to offer their personal perspectives on the subject. It’s a carefully considered approach that will hopefully prompt action, and fast.

Greenland into White by Paolo Solari Bozzi is published by Mondadori Electa, ISBN 978-8- 89181-238-4 and is priced at £55.

To see more of Paolo’s work visit www.solari-bozzi.com.