While the overwhelming majority of photographers now use digital, there can still be great delight in shooting film. With each exposure costing money, it imposes a slower, more contemplative approach. Film cameras are also often wonderfully tactile to shoot with, particularly fully manual and mechanical models.

Many old cameras are still eminently usable, just as long as they use 35mm or 120 roll film. Some don’t even need batteries, except to power their exposure meters. Even formerly high-end models can be surprisingly cheap, especially when bought through online marketplaces such as eBay. However if you’re planning on using one seriously, it’s best to spend more money with a proper dealer, who would have checked the camera thoroughly and will likely offer some kind of guarantee.

Prices of film cameras vary widely, depending on their condition and from where you buy them. I’ve included indicative values, but expect to pay more for an example in excellent nick, or less for a battered one. Bear in mind that any camera can have problems that only become apparent after shooting a roll of film, so caveat emptor.

Halina 35X

- 35mm fully manual compact

- No battery needed

- £10

Introduced in 1959, this is a particularly cheap and cheerful introduction to film photography. The Halina 35X is a very basic camera that manages to look much more sophisticated and expensive than it really is. It employs a simple, uncoated 45mm f/3.5 Halina Anastigmat lens which stops down to f/16, scale focusing to 3ft, and four timed shutter speeds from 1/200 to 1/25sec, along with a Bulb setting. There’s a tiny direct-vision viewfinder, but no meter or focusing aid. The film is advanced using a large knob on the top plate.

When shooting, it’s crucial to remember to reset the shutter using a lever on its side, as otherwise it won’t fire when you press the button. However the double-exposure prevention mechanism will still activate, meaning you’ll get a blank frame.

Minox 35EL

- 35mm aperture-priority compact

- PX27 battery

- £50

If you want a 35mm compact that can be used in aperture-priority auto mode, then a Minox might be the answer. The firm is best known for its iconic spy cameras, but it also produced tiny 35mm cameras. The 35EL is the original, with later models adding extra features.

The Minox 35EL has a plastic body shell, with a removable back for loading film. The focus distance and aperture are set using small rings around the lens, while the ISO dial is on the baseplate. During shooting, the shutter speed selected by the camera is shown on a large scale at the right side of the viewfinder. Oddly there’s no way of attaching a strap; you either have to screw one into the tripod socket, or use the ever-ready case. The camera won’t work without a battery, but silver-oxide PX27 replacements are readily available.

Canonet QL19

- 35mm compact rangefinder

- PX625 battery

- £70

The 1960s and ’70s saw a proliferation of high-quality 35mm compact rangefinders, with perhaps the finest being made by Canon and Olympus. The Canonet range progressed through multiple generations, each with three different lens speeds (f/2.8, f/1.9 and f/1.7). The third-generation QL17 GIII is a classic that’s beloved by street photographers, but has a three-figure price tag to match. This second-generation version has most of the same features but a slightly slower lens for a lower price; however it’s not so easy to find.

This is a small, well-made camera based on a 45mm f/1.9 lens and a large viewfinder with a bright, clear rangefinder spot in the centre. All of the main controls are grouped around the lens, with the focusing lever placed closest to the body. The aperture ring has no click-stops, which makes it easy to use intermediate settings, and an A position for use in shutter-priority auto mode, which is the only time you’ll need a battery. The Canonet is a joy to use and capable of great results.

Rollei 35 T

- 35mm fully manual compact

- PX625 battery

- £100

Few cameras polarise photographers’ opinions quite as much as the Rollei 35. Some consider it a timeless classic, while others decry its eccentric, impractical design. Personally I love it.

Rollei 35s came in several designs. The cheaper B 35, C 35 and 35 LED used three-element Triotar lenses, while the premium 35 S had a five-element f/2.8 Sonnar. The classic original version, however, is based around a scale-focusing four-element 40mm f/3.5 Tessar lens.

This camera was originally sold simply as the Rollei 35, but later rebadged as the 35 T for consistency with its sister models. The shutter speed and aperture are set using front-plate dials, while looking down at the match-needle meter on the top-plate. Additional inset dials on the front set the film speed and provide a reminder of the film type loaded. The camera gives best results using zone or hyperfocal focusing methods, via the clearly marked distance and depth-of-field scales on the lens.

Olympus μ[mju:]-1

- 35mm autofocus compact

- CR123A battery

- £50

On the whole, 35mm autofocus compacts lack the attraction of older manual-focus cameras, with their plastic bodies and reliance on battery-driven automation. A few certainly stand above the crowd though, including Olympus’s weather-proofed mju line. The best of these, the tiny f/2.8-lensed mju-II, will set you back around £200, which is considerably more than it cost when new. Thankfully its predecessor, the mju-1, is much more affordable.

The camera features a capsule design, with a cover that slides to one side to reveal the 35mm f/3.5 lens. Operation is almost entirely automatic, with just two buttons on the top to set the flash mode or activate the self-timer. Like most of its contemporaries, the mju-1 focuses in the centre of the frame, and while this is clearly marked in the viewfinder, it can still result in focus errors if you’re not careful. Aside from that, it’s a competent and versatile point-and-shoot.

Olympus OM-1

- 35mm fully manual SLR

- PX625 battery

- £100 with 50mm f/1.8

For anyone who wants to learn the basics of photography, there’s a real attraction to fully manual 35mm SLRs. Many such cameras are big and clunky, but in the early 1970s Olympus changed all that with its OM system. The OM-1 was unusually compact compared to its contemporaries and backed up by an extensive line of small, high- quality Zuiko lenses. Even now, it’s a lovely camera to use.

The camera offers shutter speeds from 1sec to 1/1,000sec, along with a Bulb setting for long exposures. Unusually, the shutter speed dial is placed around the lens mount for control with your left hand, with the aperture ring positioned at the front of most lenses to avoid confusion between the two. A top-plate dial sets film speed. Metering is via a simple centre-weighted match-needle system, and is the only thing that requires a battery. But possibly the OM-1’s standout feature is its huge viewfinder, which at 0.92x magnification is significantly larger than that on any DSLR.

Ensign Selfix 16-20

- Medium-format folding camera

- No battery needed

- £50

English manufacturer Ross-Ensign made a number of folding cameras during the 1950s, all using 120 medium-format roll film. The most desirable is the rare rangefinder-focusing Ensign AutoRange 820, which shoots 6x9cm frames and commands a four-figure price tag. At the other end of the scale we find the altogether more affordable and easier to find Selfix 16-20, which takes 16 6×4.5cm frames on a 120 roll. It came in two main versions, with either a fixed or folding viewfinder, each of which could be fitted with a range of lenses. The nicest variant has the folding viewfinder and a 75mm f/3.5 Ross Xpres lens. To focus, you simply use a distance scale on the lens.

Indeed this is a lovely little camera, and a great way to experiment with medium-format film. Perhaps its main attraction is its coat-pocketable size, at just 12.1×9.4×4.2cm when folded. Its oddest feature is the left-handed shutter button, with an inset spike that painfully pokes you in the finger if you forget to cock the shutter!

Canon EOS 3

- 35mm autofocus SLR

- 2CR5 battery

- £200 (body only)

Canon’s late-1990s powerhouse was one of the most technically sophisticated film cameras ever made. With a design based on the flagship EOS-1 line, but a less rugged polycarbonate shell, its impressive specification includes a top shutter speed of 1/8,000sec, continuous shooting at 4 frames per second (or 7fps with the optional booster grip) and a sophisticated 45-point autofocus system. The latter employs Canon’s unique eye-controlled focus technology, with the camera selecting the AF point based upon where in the frame the user is looking. This is a fantastic feature for those who can get it working properly, although many photographers find it too unreliable.

Those interested in shooting slide film will benefit from the 21-zone evaluative metering, along with the handy multi-spot metering system that allows the user to assess the brightness range of the scene and expose accordingly. Best of all, the EOS 3 works perfectly with the latest lenses. But at 161x119x71mm and 780g, it’s a big beast.

Nikon F90

- 35mm autofocus SLR

- 4 x AA batteries

- £70 (body only)

This chunky SLR dates from the early 1990s, and was considered Nikon’s first camera to really challenge Canon for autofocus speed. Its solid build and impressive specification meant that it was widely adopted by enthusiasts, and it’s still a very capable camera today. Its main limitation is that it has only one AF point in the centre of the frame, although with a choice of wide and spot modes.

Aside from that, pretty much everything you might want is on board. This includes shutter speeds up to 1/8,000sec, 3.6 frames per second shooting, and eight-segment 3D Matrix metering that takes subject distance into account. The viewfinder is large and bright, at 0.78x magnification, with interchangeable focusing screens.

This being Nikon, however, there are limitations if you wanted to use the F90 with modern lenses. The aperture is set using a ring on the lens, so G-type lenses can only be used in program or shutter priority modes. The latest E-type lenses won’t work at all.

Fuji GSW690 III

- Medium-format rangefinder

- No battery needed

- £600

Fuji was a serious player in medium-format film photography, making both SLRs and rangefinders. The GSW690 III is of the latter type, and sports a fixed 65mm f/5.6 lens, equivalent to a 28mm wideangle.

Don’t be fooled by appearances, though. The GSW690 III shoots huge 6x9cm frames on 120 film, and everything has to be scaled-up to match. So while in photos this might look like any other rangefinder, in reality it’s massive. Indeed at about 20cm wide, 12cm high, and 13cm deep including the lens, it’s nicknamed the ‘Texas Leica’.

Operation is extremely simple. Focusing employs a ring around the lens, with a small rangefinder spot in the middle of the viewfinder. The shutter speed and aperture are set using dials at the front of the lens which are only operable by sliding the lens hood forward (this makes the camera near-impossible to use with square filter systems). There’s also no built-in meter. Don’t let this put you off, though, because the 6x9cm transparencies it can produce are objects of rare beauty.

Fujifilm Instax 100

- Point-and-shoot instant camera

- 4 x AA batteries

- £30

Instant photography has enjoyed a resurgence in recent years, fuelled by both Fujifilm’s Instax range and the sterling efforts of Polaroid Originals (formerly Impossible Project) to keep the iconic square format alive. But if you want reliably attractive prints, it has to be Instax, with the biggest and boldest being Instax Wide.

A new Instax 300 Wide camera will set you back £100, but you can buy the first-ever Instax model, the 100, for a fraction of that price. In terms of features, there’s practically no difference between them, although the 300 gains a tripod mount.

Again the large format results in a bulky camera, and at 17.2x12x9.2cm the Instax 100 is about as far from pocketable as you’ll get. It includes the usual sparse feature set, namely a lighten/ darken control, flash on/off, and the ability to select between close and distant focus settings. Film is expensive, at £17 for 20 shots, but there’s a real attraction to the fact that every single print is unique.

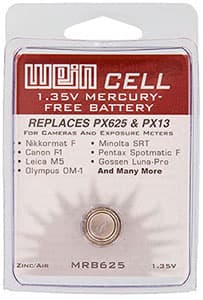

PX625 battery replacement

PX625 battery replacement

Many cameras from the 1970s were designed to use the now-banned PX625 mercury cell.

Avoid 1.5V alkaline replacements, as they will usually give inaccurate meter readings, and instead use 1.35V zinc-air Wein cells, which cost around £7 each. Just be aware that the battery will slowly discharge from the moment it’s activated by peeling off the cover.

Three essential accessories

- Lightmeter For cameras with no meter (or a broken one), the easiest option is probably to use a smartphone app. But for a more authentic experience, you could use a vintage lightmeter, or a modern option such as the Gossen Digisix.

- Rangefinder This gadget can be used to measure the focus distance for scale-focusing cameras that don’t have their own focus aid. Simply rotate the dial to bring together the two images, read the distance and transfer it to the lens. Most can be mounted on the camera’s accessory shoe.

- Cable release When you need to shoot with a slow shutter speed, most vintage cameras use universal screw-in cable releases.