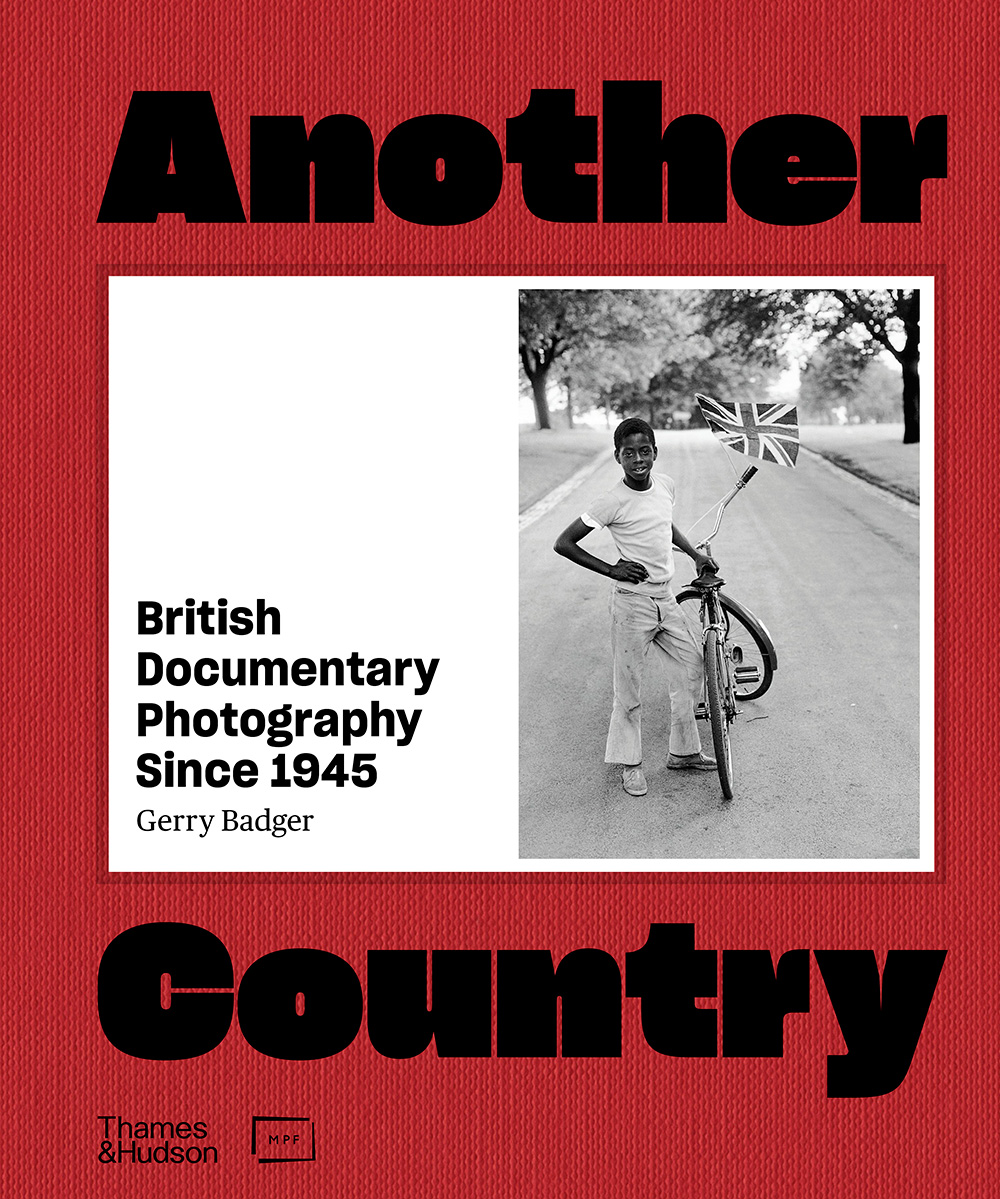

Writer, curator, and photographer Gerry Badger’s superb new book “Another Country: British Documentary Photography Since 1945” brings together works taken by more than 160 photographers over the past 80 years.

Here, Badger talks to us about the book, the history of documentary photography after 1945, and its role in British society.

All photographers love to travel and make work in exotic places. Why not? It’s work and surrogate holiday in one. But it’s a truism to say that the best work done by a country’s photographers is documenting their homeland, or adopted homeland. That’s where they have the biggest stake.

So a history of postwar British documentary photography is a history of the country through specific eyes. Which is why the book is titled Another Country. It is not, and can never be an impartial view. And although a ‘documentary’ view, it is actually a complicated fiction, although that in general means a fiction aiming to tell a truth.

But what is ‘documentary’ photography? The traditional view is that it is inherently ‘straight’ photography – the photographer observes and reports on something, thus making a record of society. But many photographers talk about society in their work, fabricating the images like a film director, even making photographic collages.

Street Musician, ‘Banjo – Jimmy Cross’, Spitalfields, London, 1972 © Ron McCormick

Lewis Balts said photography was ‘a narrow but deep area between the film and the novel’; in this way one can embrace a wider definition of the documentary, viewing it as an attitude – a desire to talk about aspects of society – rather than a style as such.

British photography in the 1940s was clearly very different from today. It tended to be regarded as a ‘trade’ rather than an art form.

Art photography was strictly the province of the camera clubs, while professionals worked to get their imagery in print in the illustrated journals and magazines – the most prestigious of which prior to the 1960s was Picture Post, edited by Tom Hopkinson and employing such photographers as Bert Hardy, Thurston Hopkins, and Grace Robertson. That magazine closed in 1957, but after a brief hiatus it was replaced by the supplemental magazines of the more serious Sunday newspapers – The Times, Observer, and Telegraph.

Blackpool, 1976-77. © Paddy Summerfield

David Bailey, Brian Duffy, and Terence Donovan became the star photographers in the commercial and fashion worlds, importantly representing photographers from working class backgrounds replacing upper middle-class figures like Cecil Beaton.

In reportage photography, David Hurn, Phillip Jones-Griffiths, and Ian Berry became members of the world’s most prestigious agency, Magnum, and together with such figures as John Bulmer, Patrick Ward, and Don McCullin working for the Sunday supplements gave British photography a greater reputation internationally.

Correct Distance, 1985-86. © Mitra Tabrizian

Towards the end of the sixties, a new spirit infused British photography, the notion of the ‘independent’ photographer, largely eschewing commercial photography and using the medium as creative self expression, as a fully fledged art form.

Photography as art had been largely confined to the photographic salons of institutions like the RPS, and although any photographer would regard their imagery in a creative light, the notion of exhibiting photographs as works of art in galleries and museums only became widespread in the 1960s, first in America, and then in Britain in the 1970s.

But photographers working independently and largely disregarding editorial work needed support and the story of British photography in the seventies and eighties is one of the support mechanisms – critical, financial, educational, and institutional – being established to encourage this new spirit in British photography and young photographers embracing the medium.

Untitled, from Stags, Hens & Bunnies, 2014. © Dougie Wallace

In the early 70s, the Victoria and Albert Museum appointed a photography curator in Mark Haworth-Booth; Sotheby’s and Christie’s began to sell photographs as works of art; the Arts Council established a photography administrator, Barry Lane, to provide grants for photographers; and Sue Davies and Dorothy Bohm founded the Photographers’ Gallery in 1971, the first British public gallery to be dedicated solely to photography.

Davies and Bohm’s London enterprise was followed by others throughout the country, such as Val Williams’ Impressions in York. The critical discourse also changed. Two ‘art photography’ magazines, Creative Camera and the shorter-lived Album, essentially promoted the modernist-formalist approach of the American art museum, an approach taken up by young photographers whose aim was to make pictures in the way of artists.

Many were attracted to British themes, inspired by the street photography of Tony Ray-Jones, figures like Chris Killip, Homer Sykes, and Paddy Summerfield. Such work, usually street photography, if not downright documentary photography, was at least in the ‘documentary mode’. The idea of photography as a useful art runs persistently through the British medium.

New Brighton, Merseyside, from The Last Resort, 1983–86. © Martin Parr

The late sixties was the age of political protest, and this was also reflected in the critical discourse of the seventies. Politically minded photographers gravitated towards the Half Moon Gallery and collective in Whitechapel, whose critical journal Camerawork – the antithesis of Alfred Stiegiltz’s early 20th century art photography magazine of the same name – questioned the representational nature of the medium and how to turn it to more progressive ends.

The Half Moon photographers, amongst them Paul Trevor, Chris Steele-Perkins, Mike Abrahams, and Robert Golden, documented the protests and social conditions of the seventies, but the Whitechapel political documentary hotbed was important for another reason.

Inspired by the feminist movement and decades of neglect by the photographic establishment, a whole generation of women photographers established their institutions and added a strong and much-needed voice to British photography.

Hand of Pork, from I Can Help, 1988. © Paul Reas

Britain had always produced great women photographers – Anna Atkins made the first photobook, Julia Margaret Cameron was arguably the finest portraitist of the 19th century, while Tudor Hart, Grace Robertson, Jane Bown, Lee Miller, and Shirley Baker made significant work, but it could be said that the seventies was the first time a coordinated phalanx of women photographers made a collective contribution. Notable figures from the 1970s include Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen, Markéta Luskacová, and Tish Murtha.

Seventies women photographers were often coordinated in a literal as well as psychological sense. For example, the Hackney Flashers Group, which included Jo Spence, Maggie Murray, and Sally Greenhill, worked to raise consciousness about women’s issues, an enterprise which culminated in their Who’s Holding the Baby exhibition in 1978, shown at various venues in 1979.

In their work, the group’s members questioned how much could actually be shown by traditional ‘documentary’ photography and sought to expand or move beyond the strict genre by employing such strategies as collage or staged photography.

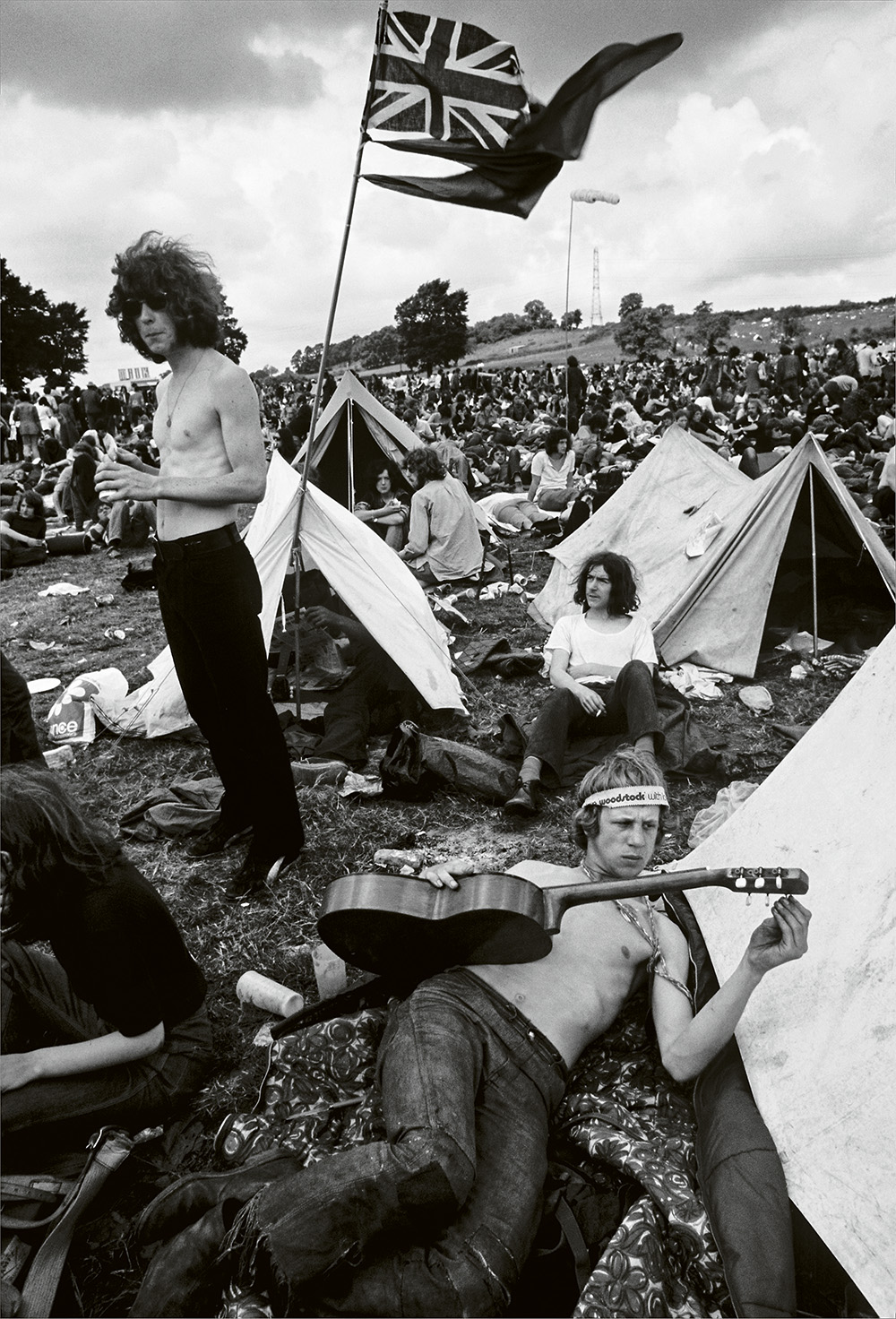

Isle of Wight Pop Festival, 1968. © Patrick Ward

Individuals also began to work in this way, such as Jo Spence (ex-Flashers), concentrating upon her own and woman’s health issues, and Karen Knorr, whose phototext pieces from the end of the decade looked at a demographic that was far removed from Whitechapel, wealthy Belgravia residents.

If the 1970s saw the support groups for women photographers established, the 1980s saw the general neglect of ethnic minority photographers at least partially ended with the establishment of the Association of Black Photographers in 1988.

As women had been, ethnic minority photographers had been working in British photography, with even less recognition, since the 1950s. Among the founder members of ABP were Sunil Gupta, Ingrid Pollard, and Rotimi Fany-Kayode. The establishment of their gallery, Autograph, under their director Mark Sealy, was as significant for British documentary photography as that of The Photographers’ Gallery or the Half Moon.

After the Swim iii, from Martha, 2018. © Siân Davey

Two further notable developments mark 1980s photography. The Margaret Thatcher government gave documentary photographers a much-changed society to document or fight against, and much of this work was in colour. The use of colour catapulted such figures as Martin Parr, Paul Graham, Anna Fox, and Nick Waplington into the limelight, while others, Chris Killip or Graham Smith for example, continued to use monochrome.

What is important is that, largely for the first time, through international festivals and wider distribution of photobooks, British photographers became internationally known and respected. This has continued, as the internet has created a global photo village, although the examination of British life and its explaining to other societies would still seem to remain the most vital project for British photography.

Oxford Street, 2002. © David Solomons

Two standout points seem to have emerged from my examination of postwar British documentary photography – apart from the desirability of widening the notion of documentary itself.

First, after the War, photography turned inwards, as did all art, becoming more and more subjective. Perhaps it was also a recognition that there is no such thing as an objective photographer – so the documentary, objective report of the war becomes ‘my diary when embedded with the troops.’ And identity has become an ever more important subject alongside social and economic conditions.

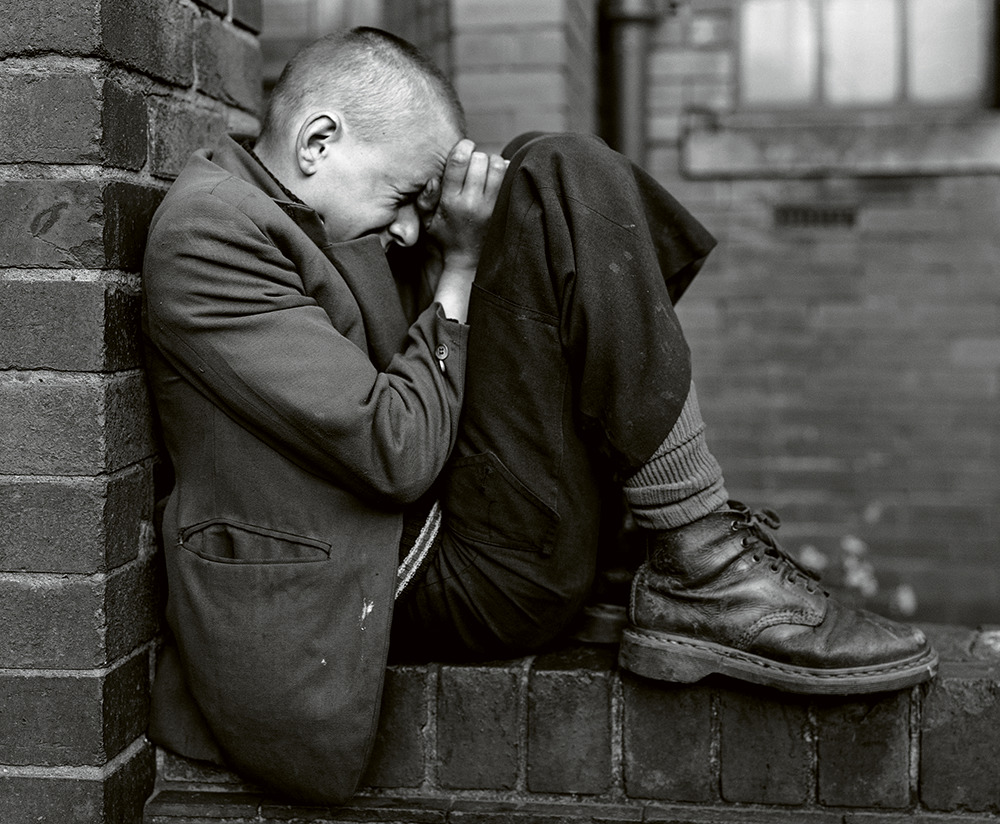

Youth on a Wall, Jarrow, Tyneside, 1976. © Chris Killip

Second, the contribution of immigrants to British photography has been profound. From Jews and other Europeans who came over in the 1930s – including our ‘greatest’ photographer, Bill Brandt – to West Indians in the 1950s and ’60s, and others from all over the world who are coming to live and work here. They have contributed immensely to the impressive diversity of the medium in this country, and given it an honoured place in the worldwide culture that is photography today.

In noting these two points, I come back to my original observation. The best subject for photographers living in Britain, as proven by British photography’s rich history, is surely Great Britain itself.

Another Country?

Another Country: British Documentary Photography Since 1945 by Gerry Badger is published by Thames & Hudson in collaboration with the Martin Parr Foundation: 19 May 2022, RRP £50 hardback. ISBN: 9780500022177.

Another Country: British Documentary Photography Since 1945 is out now on Thames and Hudson.

Related articles:

Our best documentary, street and architecture photography tips

Best cameras for photojournalism and documentary 2022