Philip Prodger’s book Face Time explores the history of portrait photography. He tells Amy Davies all about this enduring subject

A compelling and comprehensive guide to the photographic portrait, Face Time is a new book by Philip Prodger. In it, he expertly walks us through a history of the portrait photography genre. From photography’s invention right up to the present day. He does this with care, consideration and a decent dash of humour to boot.

Currently a Senior Research Scholar at the Yale Center for British Art, his varied career as a curator in a number of prestigious institutions perfectly places him to write the book. Maybe none more so than his stint as Head of Photographs at the National Portrait Gallery in London.

Earlier this month, I was able to put my questions about a genre which is described by Philip as ‘one of the most difficult undertakings in art’ to him. Pleasingly, he responded to them with the same warmth, wit and care that is is displayed in abundance throughout his book.

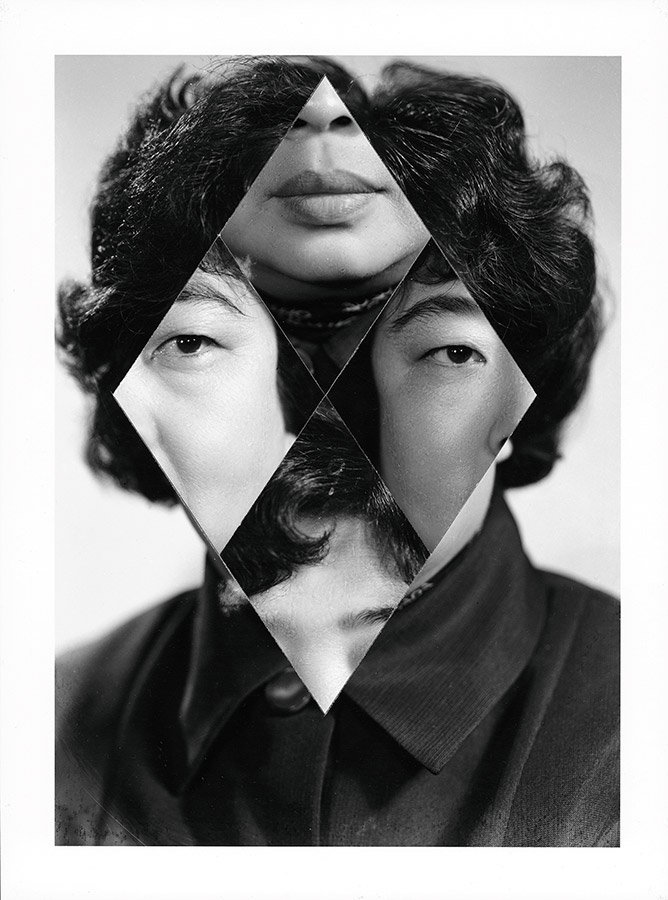

Kensuke Koike and Thomas Sauvin, ‘Untitled #21 from the series No More, No Less’, 2016-2017. Image credit: Kensuke Koike and Thomas Sauvin

History of Portrait photography – what is a portrait?

The most obvious question to start with for somebody like Philip is to lay the groundwork and decide exactly what is a ‘portrait’. Aside from a straightforward definition as a picture of a person – the answer may not be as simple as you might expect. Philip says, ‘I think if you asked different curators you would get different answers to this question. But, for me, the difference is capturing something of a person’s identity – not just the way they look, not just the physicality of their features, but actually something of their personality, who they are and how they’re different from other people.’

At AP, we admittedly have a tendency to draw quite hard divisions between the photographic genres. In our portrait premium issues of the magazine we focus on portrait photography; with other similar or overlapping genres, like street and documentary, perhaps not traditionally falling into the same category and usually meriting a special of their own. As an academic and interrogator of contemporary practice however, Philip has a different opinion.

Floyd Rankins, Theopholus Bracket, Old Swampscott Fisherman, n.d., gelatin silver print. Image courtesy of the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, MA.

‘Frankly, in this century, there are no longer any bright lines between these different divisions – and I think that’s all for the best. I’m not sure that social documentary, or street photography, is a very satisfactory term on its own – but there’s no question that there are many portraitists who are working out in the world, in the communities, out on the street and they’re photographing people and showing us something about their story.’

How to make a great portrait photograph

Probably as anyone who undertakes the genre will tell you, portraiture is not easy. That’s not to say there isn’t skill in other genres, but it’s a simple fact that pointing your camera at a beautiful landscape, odds are you’re going to get a decent shot. The same can’t be said for pointing your lens at a person. With so many variables at play, it’s no wonder Philip describes it in the book as so tricky to master.

He explains, ‘I think that a great portrait is like a dance. You have the volition of the photographer, and the will and personality of the sitter. It’s about finding and negotiating that space. That’s an incredibly difficult thing. You’ve a kind of push and pull that’s going back and forth between the photographer and sitter, and finding that moment where you capture something unique and special is very difficult indeed.

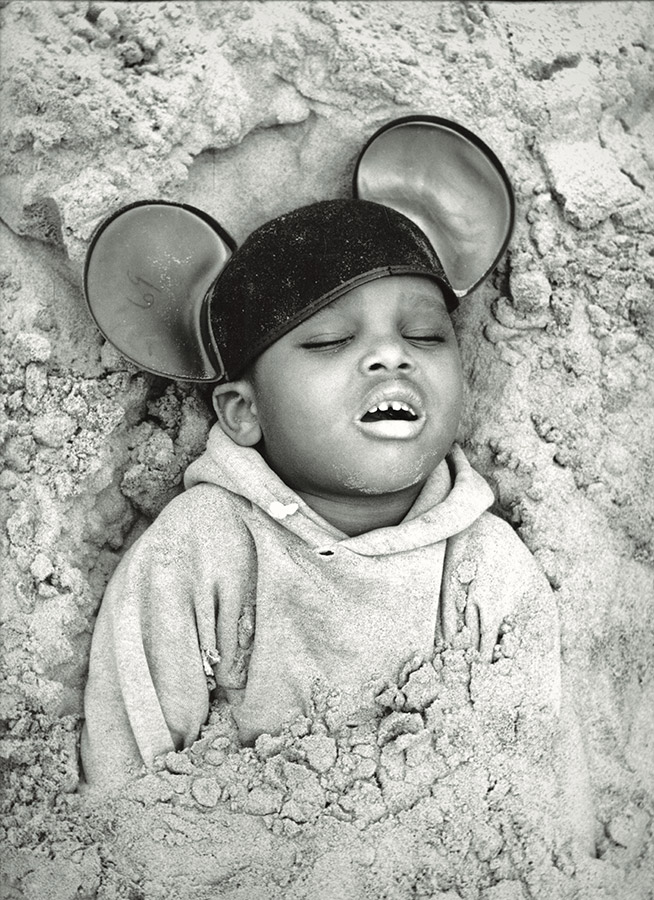

Arthur Tress, Child Buried in Sand, Coney Island, 1968, gelatin silver print. © 2018 Arthur Tress Legacy Trust

‘I would also add that we ask an awful lot from portraits. We want our portraits to tell us something fundamental about the sitter, but we’re confining ourselves to whatever the exposure time is of that photograph – perhaps 1/60th of a second. The idea that you could condense everything that’s worth knowing about a person at that moment into 1/60th of a second is just absolutely extraordinary. A photographic portrait is uniquely powerful in that somehow that tension, where you have to condense everything down to a millisecond, makes it resolve somehow. When the photograph falls into place, it’s like no other form of communication.’

The sad news for readers of AP looking to recreate some of the great masters of portraiture is that defining how to achieve all of the above is nigh-on impossible. ‘I’m not sure I could put it into words,’ confirms Philip. ‘It’s one of those things, when you see the photograph and you’re moved, and you know you’ve seen a great photograph – but there’s no formula. There’s so many different ways of making a portrait. It can be done in the studio, it can be done in the street, it can be done with careful planning, it can be spontaneous. There’s no single recipe that will you get you to a great portrait photograph.’

Weronika Gesicka, Untitled #32, 2016 from the Traces series, 2015-2017. Courtesy Weronika Gęsicka and JEDNOSTKA Gallery

History of portrait photography vs today’s culture

There’s an interesting section in Face Time which discusses both the male gaze and the colonial gaze. These oft-controversial topics split opinions frequently – some will roll their eyes at a so-called ‘woke agenda’, while others will ferociously argue for our awareness of the issues. It’s safe to say that Philip lands somewhere near the latter. ‘We just need to be aware of the practices of the past,’ he explains. ‘I’m really struck that even when I was a younger curator, the things that male photographers thought were okay, they no longer think is okay – and you know what, the world is better for it.

We need to be absolutely careful that we’re not excluding anyone, and that we are embracing the fullness of human experience and treating people as equal. That’s actually what I think is so fabulous about portrait photography – we are all equal before the lens. Photography can be such a powerful tool to be welcoming and inclusive, to include all kinds of different perspectives.

So much ink has been spilled over the male and colonial gaze – and you know, much of it is absolutely right. But as a photographer, the question going forward must be how are we going to improve our practices and make our photography that much more interesting, compelling and inclusive.’

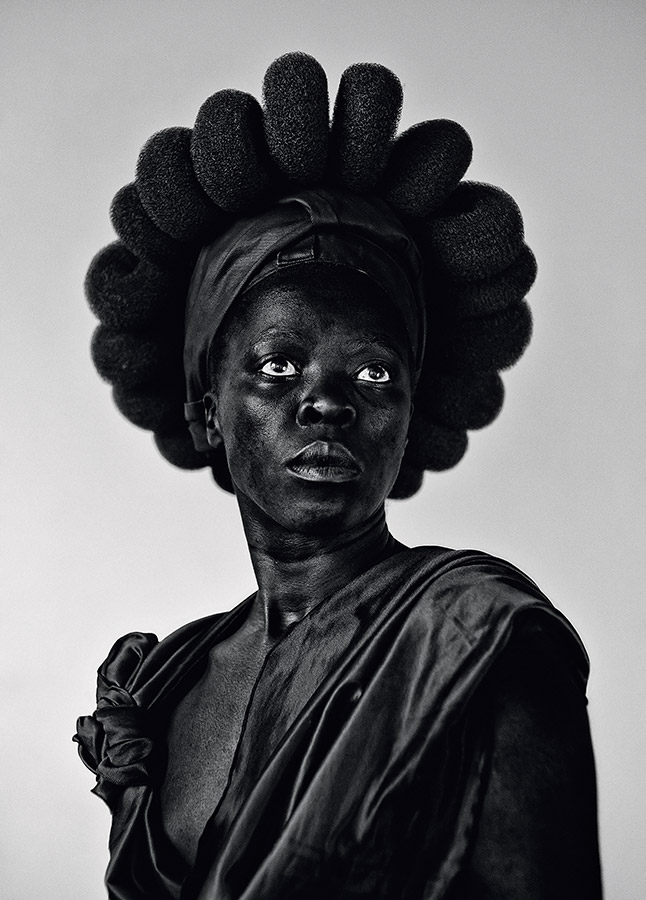

Zanele Muholi, Ntozakhe II, Parktown, 2016. Courtesy of Stevenson, Amsterdam/Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancy Richardson, New York/© Zanele Muholi

Portrait photography and the Taylor Wessing prize

Moving on to another sometimes controversial topic – the Taylor Wessing Photographic Portrait Prize, organised by the National Portrait Gallery. This annual, prestigious portrait prize has been the leading international portrait competition for almost two decades. As the NPG’s former head, Philip was heavily involved in it, and is no stranger to the criticism oft-levied at the awards. Namely that all of the subjects tend to look depressed, miserable or at the least, far too serious.

Indeed, AP has published opinion pieces and received numerous letters from readers decrying the lack of smiles at the annual awards. In Face Time, Philip references neutral expressions tending to be taken more seriously, so it seems that the two are intrinsically linked. He laughs, perhaps somewhat knowingly, at my suggestion that this neutrality is mistaken for misery.

‘You know, I would turn it around. I’d say that there are all different emotional expressions that are really powerful and alive – and it’s not that neutral expressions are not, but there’s a sort of convention in photography that people will have those neutral expressions. It dates back to the 19th century, where a smile wasn’t possible due to slow exposure times.

‘But I’d also say that it’s really hard – in some ways it’s harder – to make a photograph that is compelling of a smiling person or a laughing person. I love them, and when I was involved with Taylor Wessing, we were always looking for photographs like that for that reason, because it does become sort of a convention. But, as I say in the book, there is this idea that if you’re sitting for a formal portrait, you want to be sort of all potentialities.

You don’t want to choose your ground. You can be happy, you can be sad, you can be angry – all of these things exist as potential within you, so you might just show the neutral and then you haven’t committed to any particular emotion. But… as you say, sometimes that can look a little bit grim.

‘I’m totally sympathetic to the suggestion, but at the same time, if one went back and looked at the actual successful portraits every year, I think you’d see a certain percentage of them are very emotional, and we were not at all interested in creating something that was a sort of study in misery.’ So there we have it.

Tania Franco Klein, Plane (self-portrait) from Proceed to the Route, 2018. Image credit: Tania Franco Klein

Emotion in portrait photography

Emotion is unquestionably an integral part of portrait photography. Prodger’s doctoral thesis, studied at Cambridge University, explored the role of photography in Charles Darwin’s study of emotions. A century and a half later, I’m interested to know where we get the ‘most real’ portraits – are studio portraits somehow less real, when the environment is stripped away? Maybe the opposite is true, and without the distraction of a background, we can truly see into the human psyche. Perhaps wishing to avoid committing too fully, Philip offers ‘it depends on the sitter’ as an answer.

‘Some people are very self-conscious. And the other side of that is that some photographers are very good at making the sitter feel comfortable and confident. That’s one of the reasons that professional portrait photographers do so well, is because they have a way of engaging with the sitter.

At the same time, part of being a celebrity – if we’re talking about people who get photographed all the time – is learning to deal with the studio and be okay with it. Some people, such as me for example, I’m horrible in the studio. It would be much better to catch me out in the world doing my thing. The studio is a very unnatural situation, and I think results from it are almost miraculous, or magical really.’

Sarah Jones, The Dining Room (Francis Place) I, 1997, Colour coupler print. Courtesy Maureen Paley, London, © Sarah Jones

Portrait photography: editing

Yet another controversial topic in portraiture is the subject of editing. There seems to be something inherently more moralistic about using image manipulation when it comes to photographs of people, compared to say a landscape, or a macro subject. It’s also true of course to say that manipulation is nothing new – for any subject. In the book for instance, Philip references From Charwoman to Dowager by Cecil Beaton – a set of three images from the 1930s which show just how fundamentally a photograph could be transformed using common darkroom techniques.

The woman in the picture has been slimmed down, her hairline lowered and thinned, her double chin removed. Sounds familiar in modern times, doesn’t it? Given our earlier discussion about what exactly is a portrait, I ponder whether when something – or someone – has been changed beyond all recognition, whether it can still bear the name portrait at all. Philip says it can – but once again it depends. ‘My personal opinion is that it depends on the photograph.

Tom Hunter, Woman Reading a Possession Order, 1997, Ilfochrome print. Ilfochrome print. Photo Tom Hunter

You said “beyond all recognition”, but that’s a very loaded term. Portraits can be very abstract – they don’t necessarily have to look like the physiognomy of the person being photographed. I’m not of the school that it ceases to be a portrait if you can no longer automatically easily recognise the figure. I think it depends on the intent of the artists and how successful they’ve been in presenting that essence of the individual. There’s an idea in art that representation doesn’t necessarily have to mean figurative exactness, that in fact, representation can mean some of those qualities about a person that a picture can elicit and they don’t have to be strictly representational.’

Final thoughts

Face Time is a book that’s been in the works for quite a while. It’s not just the often relatively slow pace of book publishing we’re talking about here, but says Philip, it stretches back even further. ‘It goes back to my earliest days as a curator and a scholar,’ he explains. ‘There’s bits in there that go back to my doctoral thesis. In fact it was great fun to put the book together, as I was able to draw along every stop of the way of my career. I pulled out photographs from every institution I’ve worked out. Of course the viewer doesn’t have to know that – it’s not particularly interesting for them – but for me it was a great privilege.

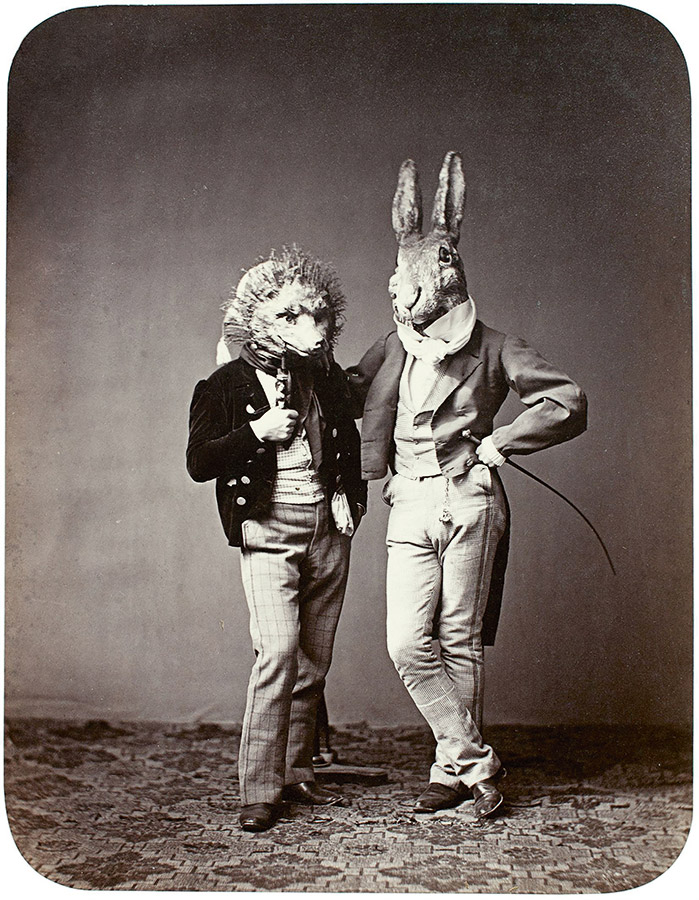

Münchner Stadtmuseum Josef Albert, Hedgehog and Hare, from the Fairy Tale Ball, 1862. Image credit: Münchner Stadtmuseum

‘The actual book started before Covid. It took several years to pull it together, and is one of those projects that would probably have been done sooner were it not for the pandemic. That said, this period of time that we’ve just been through – with the shutting down of certain kinds of social interactions and intensifying of others; it’s really poignant. I think it’s a really good book to read in the wake of Covid (let’s hope it’s the wake) – it really brings home a lot of these issues around social interaction – and portrait photography is nothing but social interaction.’

Philip perhaps sums it up best in the book itself: ‘Ultimately, all portrait photography is social. Like all art, portraiture has many different and sometimes overlapping purposes. Arguably the most notable, powerful and enduring is also the simplest. It heals, comforts and strengthens – by reminding us we’re not alone.’

I can’t resist one last question before our enlightening conversation ends. The name of the book: is it a play on the Apple software, that among others, exploded in popularity over the past couple of years – or not? ‘No – it was not a play on the Apple product at all,’ Philip answers. ‘It was just an attempt to get out this question of faces, and 95% of all portraits zero in on the face – something which I discuss in the book.

The idea that the photographer is looking at the face, and then the face is looking at the photographer. Then, the image is displayed in print or on a screen, so the viewer is looking at the face. It’s a whole chain reaction of faces – and interpretation and expression… so we thought that was a good title.’

Face Time: A History of the Photographic Portrait by Philip Prodger is available to buy now. Published by Thames and Hudson, RRP £30. ISBN: 9780500544914

Further reading

Best photography books of 2022

Best women photographers: an alternative history of photography

Beginners guide to Portrait photography

Best cameras for portraits and portrait photography 2023