Chekmenev erected a simple white sheet behind the sitter to achieve the passport photos

Sometimes photographers find themselves in extraordinary political circumstances. It could well be they’ve sought them out, such as Mark Power when he travelled to Berlin in November 1989 to document the elation of the crowds as they witnessed the fall of the wall that separated East from West. Or maybe a photographer is thrown unwittingly into a situation, a good example being Stuart Franklin, who was there to witness a defiant student stand his ground against a military tank in China’s Tiananmen Square. These are examples of grandeur, of world-changing events. But sometimes the photographer finds himself or herself involved, through circumstance, in something small and intimate, but no less extraordinary.

In the early 1990s, the mighty Soviet Union had all but dissolved. The empire’s boundaries began to shrink and the countries held within its iron grip were finally in a position to claim independence. One such nation was the newly autonomous Ukraine, a country that continues to struggle in its relationship with Russia to this day. Once Ukraine had wriggled free of its shackles it was in an odd bureaucratic quandary. When it was part of the Soviet Union, Ukraine’s 52 million citizens held Soviet Union passports. That stands to reason. However, now Ukraine was no longer part of the Soviet Union, every single citizen’s passport was nullified. This would require a headache-inducing solution. Every citizen needed a new passport, one that identified him or her as a resident of Ukraine. You can see how this could be a problem. As can often be the case with these things, the government of Ukraine set themselves a mind-boggling deadline to achieve this – just one year.

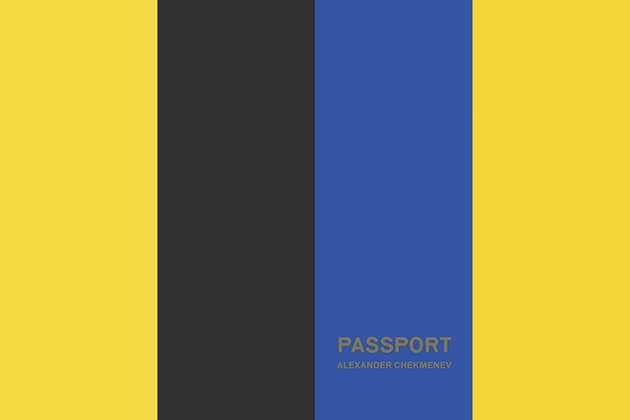

One region of Ukraine that was forced to undergo these changes was Luhansk, which sits in the southwest of the country. Between 1994 and 1995, social services in the area began employing photographers who were tasked with travelling to the homes of the elderly and ill, individuals who lacked the funds to pay for a photographer themselves. One of those photographers was Alexander Chekmenev. This book, Passport, is a record of the work he did during that year-long national campaign.

A closer look sometimes reveals fascinating details – note the medals and tattoos

Door to door

Perhaps the first thing that strikes you, as it did me when I first looked at the images: why? The subjects of Chekmenev’s images are old or are in a state where they are unable to move by themselves or in some cases not even of sound mind. Why then did Ukraine launch such an accelerated campaign to ensure every citizen had this inconvenience thrust upon them? Clearly Chekmenev’s sitters were in no rush to set off on a jolly jaunt to the African savannah any time soon. Some, as I’ve said, were bedridden and incapable of even telling you their own name.

Perhaps it has something to do with Ukraine’s newfound independence. For years and years, the relationship between Russia and Ukraine is one soaked in blood and warfare. Events in the 20th century had seen Russia run roughshod over Ukraine soil, using it as a pawn in military strategy and desperately clinging to it due to its position on the world map. The mountainless Ukraine is an inviting invasion ground for Western forces wishing to strike at Russia – with that in mind, it’s in Russia’s best interests to keep Ukraine under its control by any means necessary. Perhaps, then, this was Ukraine’s desire to quickly establish itself, in a small bureaucratic way, as independent of its lifelong tormentor.

Chekmenev’s images give us an insight into the conditions in which some of his subjects existed

Passport opens with a small collection of the final prints used in the passports. Nothing special there. But when we move on to later pages, we find the original uncropped images. Each of the sitters is in their living room or bedroom. There’s a white sheet behind them. Around them is the paraphernalia of their lives: pictures, cups, books, bed sheets. It’s a deeply moving experience to see these sitters within their own personal context.

On one occasion, Chekmenev took 60 pictures in one day. He discovered soon after that one of the subjects had died. One woman he visited was so near the end of her life, she had prepared her own coffin. She lived in one room. The coffin was in the other. On more than one occasion, the intrusion of Chekmenev and the social workers was so traumatic the sitters broke down in tears and begged them to leave.

After all this, the process went well over deadline. The passports ended up being several years in the making. The Soviet passports remained valid until 2000. All in all, Chekmenev’s incredible and haunting study of rampant bureaucracy puts things in perspective. Maybe think twice next time you find yourself complaining about filling in a tax return.

Often the social workers assisted in propping up the sitters for Chekmenev’s shots

SCORE: 5 out of 5

Published by Dewi Lewis

Price £35, 156 pages, hardback

ISBN 978-1-911306-06-1

Related reading: