A Mozambican refugee on the Dona Ana Bridge over the Zambezi River, Mozambique, 1994

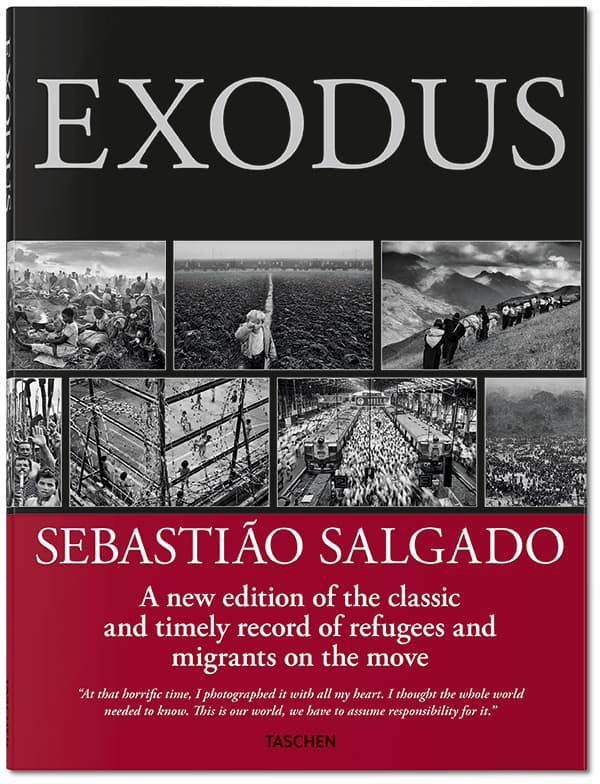

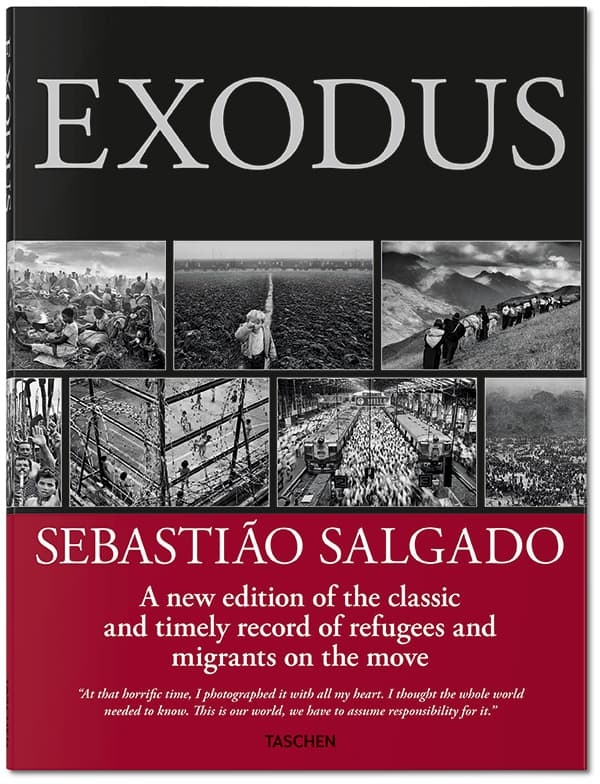

The more things change, the more they stay the same. That’s perhaps the greatest lesson to take from this reissued volume of Sebastião Salgado’s Exodus, a body of work that was six years in the making. Turn on the news, or read the headlines – migration is the big topic. Exodus documents Salgado’s travels to 35 countries, during which time he documented the displacement of a variety of migrant communities.

His journey found him treading the ground of road, slum and camp, where he encountered Latin Americans entering the US, Arabs and sub-Saharan Africans attempting to reach Europe by boat, and Hutu refugees, among many others.

Salgado’s work has become known for its vast sweeping scope, and that is certainly present here. Landscapes stretch to the horizon; crowds of people appear as swarms of ants; the sun drenches a barren desert. But that’s to perhaps overlook the opposite approach that Salgado often utilises.

Salgado strikes a nice balancing act between the micro and macro view. Ample space is dedicated to the smaller details, and it’s perhaps these images that are the most affecting. When we’re allowed to get closer in, to notice the dirt under the fingernails, to spot the bandage on a leg, to meet the haunted gaze, that’s when the project truly takes hold.

What Salgado is attempting to do, and does rather well, is document the commonality of the global migrant crisis and place you the viewer within the context. We all play a part in this, both knowingly and unknowingly. This is our global crisis. There is no us and them. There is only us.

Rwandan refugee camp of Benaco, Tanzania, 1994

Beautiful tragedy

The question is how far we should go when making suffering and hardship beautiful? Do we lose something when the things we see are rendered into aesthetic palettes of masterful tonal range and considered composition?

It’s a question often levelled at all forms of photojournalism, particularly competitions such as the World Press Photo. Even Hollywood director Steven Spielberg found himself in the firing line after many found the highly stylised Schindler’s List to do nothing more than undermine the true horror of its subject.

In defence, there’s a strong argument to be made that the photographer’s foremost task is to grab the viewer’s attention. Salgado is certainly adept at that. His images are, in the most literal sense, breathtaking. He appears to have witnessed almost impossible scenes of beauty, regardless of the subject, and has somehow captured them through the lens of his camera.

He appeals, perhaps quite deliberately, to the most superficial visual parts of our brains. Once that image has been digested, the reality of the message begin to seep into our conscience and we begin to question exactly what it is we’re seeing. He inspires, quite crucially, genuine empathy.

Churchgate Station, Bombay (Mumbai), India, 1995

But of course it’s easy to focus on the more challenging images of Salgado’s work. The fact is, Exodus is so much more than the bleak stuff. If anything, the images are a true testament to humankind. Despite the subject matter, the images can, at times, be replete with joy and admirable endurance. Even in the face of such hardship, the human spirit carries something of a flame.

On another level, something about the black & white look of the images gives the overall feel of the project a strange edge. It feels almost like Salgado isn’t there at all, that some floating objective eye on a scouting mission has delivered the images to teach us something about the world we live in.

It’s a stark contrast to the pretty postcard, and wholly subjective, approach of a photographer such as Steve McCurry. It’s perhaps this aesthetic that makes the overall message of the work so successful. There are no colourful distractions. What we’re seeing is the raw meat of the situation. Beautiful as they are, these images carry a weight that cannot so easily be shaken off.

These pictures may have been taken years ago, but the subjects we see in Exodus are so familiar as to be unnervingly uncanny. It’s a small thing, perhaps, to produce a photographic body of work to highlight these issues. But the fact is, no matter what you may think of him and his work, he is a photographer who is out there doing something. That’s more than can be said for most of us.

Score: 5 out of 5

Published by Taschen

Price £44.99, 432 pages, hardback

ISBN 978-3-83656-130-3